Some artists leave us too young. But they leave behind a wonderful collection of work and a wistful sense of what could have been.

One such artist is Virginia Frances Sterrett (1900-1931). This is her story...

One such artist is Virginia Frances Sterrett (1900-1931). This is her story...

Virginia Frances Sterrett was born in Chicago in 1900. From an early age she preferred to draw rather than play with other children.

After Sterrett's father died she began to study at the Art Institute of Chicago. Sadly she left in 1916 after her mother became ill.

At 17 Sterrett was responsible for supporting her whole family, working in art advertising agencies around Chicago to earn her living. Two years later she was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

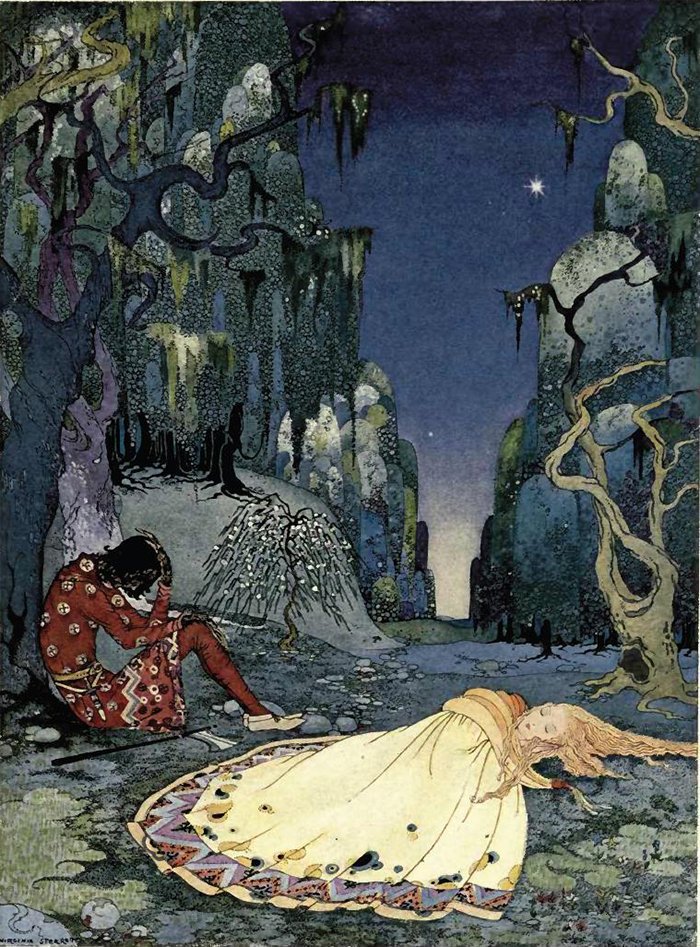

Sterrett received her first commission at the age of 19 to illustrate Old French Fairy Tales for Penn Publishing, earning $500 for eight watercolors and 16 ink drawings.

In 1920 Penn Publishing asked Sterrett to illustrate Tanglewood Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne. After completing the work her family moved to Pasadena, hoping the climate would aid her health.

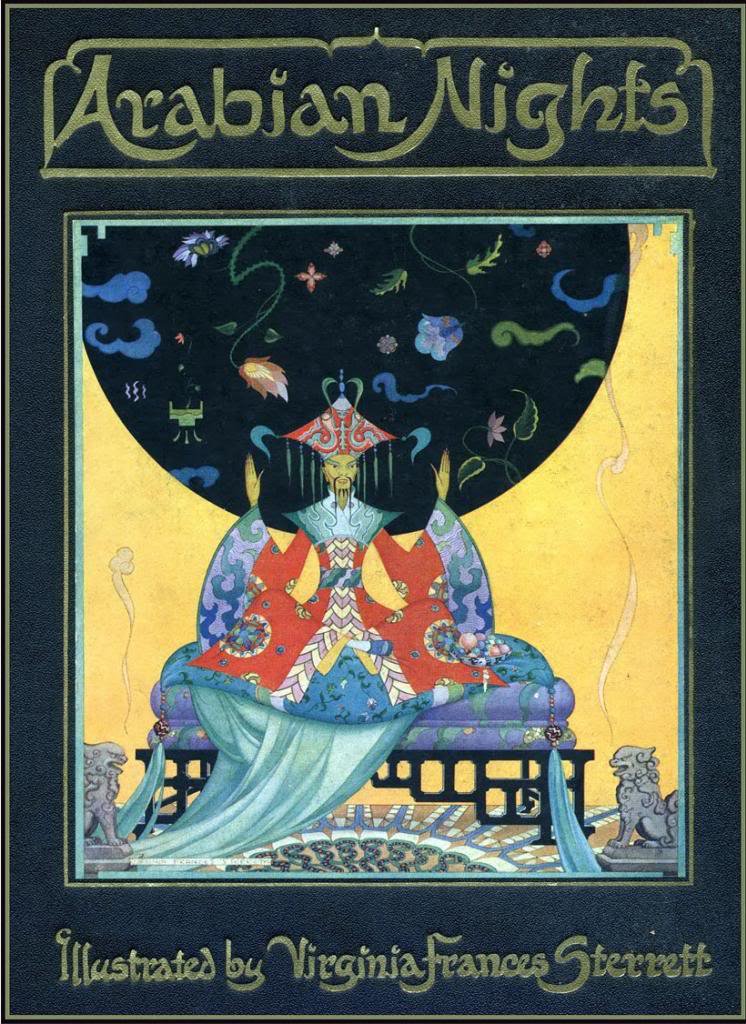

As Sterrett's tuberculosis grew worse she found she could only draw for a short period each day. In 1925 she started what would be her final completed work - her own interpretation of Arabian Nights.

Arabian Nights took Virginia Frances Sterrett three years to complete, working for a couple of hours each day. It was finally published by Penn in 1928.

In 1930, Sterrett started her last commission - Myths and Legends. Sadly it was never completed.

Virginia Frances Sterrett died of tuberculosis on 8 June 1931, at the age of 30.

Virginia Frances Sterrett died of tuberculosis on 8 June 1931, at the age of 30.

The St Louis Post-Dispatch said of Sterrett's work: "Her achievement was beauty, a delicate, fantastic beauty, created with brush and pencil... she made pictures of haunting loveliness."

Virginia Frances Sterrett's first book - Old French Fairy Tales - is available free online. Do take a look at her wonderful work if you can: publicdomainreview.org/collections/ol……

More stories another time...

More stories another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh