About two years ago I wrote a series of essays on Lia DiBello's research into business expertise.

Her work has been hugely influential to me — it's changed the way I view business, and affected the way I think about my growth as an operator.

That series WAS paywalled ...

Her work has been hugely influential to me — it's changed the way I view business, and affected the way I think about my growth as an operator.

That series WAS paywalled ...

But as of yesterday, I've made it available to everyone: commoncog.com/setting-busine…

I'm doing this because Commoncog's essays over the past two years have been pretty much about a) business expertise, or b) about methods to accelerate the acquisition of that expertise.

But that business expertise has a shape, and I wanted to make that shape explicit.

But that business expertise has a shape, and I wanted to make that shape explicit.

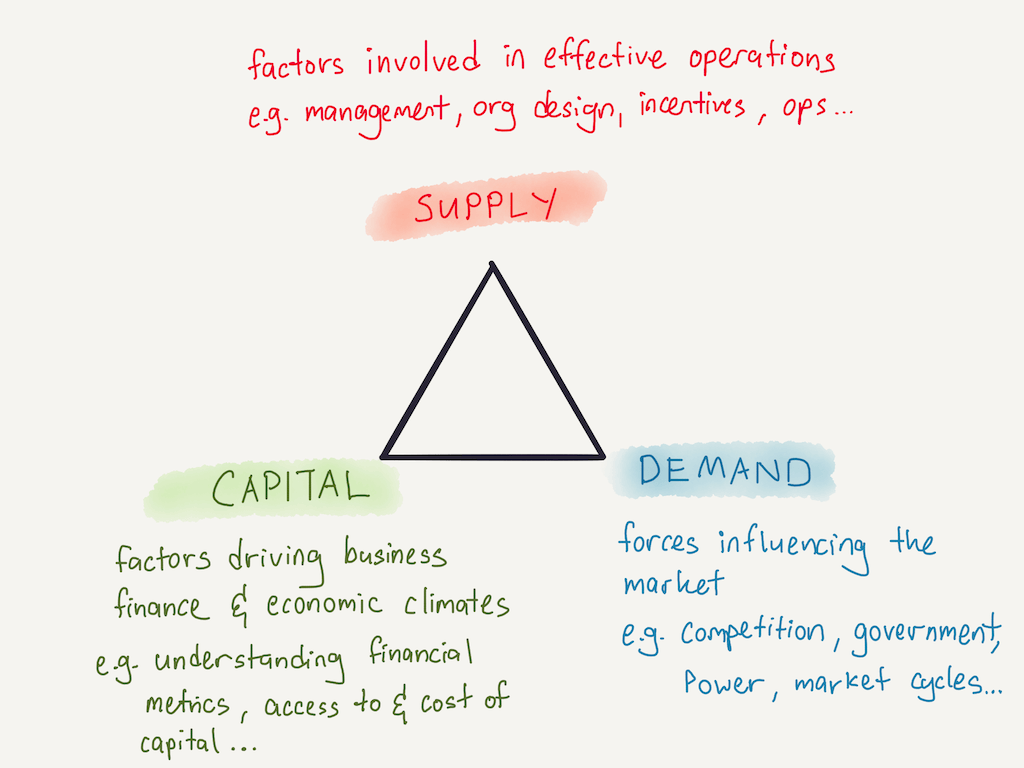

Basically experts in business deeply understand 'supply', 'demand' and 'capital' in their respective industries, and grok how changes in one leg of the triad affects the others.

The thread where I originally get into this is still pinned on my profile:

The thread where I originally get into this is still pinned on my profile:

https://twitter.com/ejames_c/status/1417689411374915584

DiBello calls this a 'triad', and it's really hard to unsee once you internalise the structure of the expertise.

Try it: read any biography of a successful businessperson, and their facility with the triad for their specific industry becomes clear quite quickly.

Try it: read any biography of a successful businessperson, and their facility with the triad for their specific industry becomes clear quite quickly.

Anyway, if you'd like to read a topic overview for Business Expertise, go here: commoncog.com/business-exper…

And if you'd like an overview of @commoncog's approach to Expertise, go here: commoncog.com/expertise/

Enjoy!

And if you'd like an overview of @commoncog's approach to Expertise, go here: commoncog.com/expertise/

Enjoy!

As a minor follow up to this … if you internalise the triad in business, it’s really striking how high the bar is for expertise.

I know exceedingly few people who are good at all three legs of the triad, and are able to reason about changes between the three legs.

I know exceedingly few people who are good at all three legs of the triad, and are able to reason about changes between the three legs.

Why? Partly this is due to age: relatively few people I know are familiar with and able to navigate the capital cycle for their industry (because they’ve not been in business long enough).

Whereas if you read biographies the triad is more stark.

Whereas if you read biographies the triad is more stark.

Conversely, the triad really does NOT resonate with business novices.

I find that it takes a little sophistication (or hard-won experience) before someone goes “oh yeah, DiBello’s claims seem right.”

I find that it takes a little sophistication (or hard-won experience) before someone goes “oh yeah, DiBello’s claims seem right.”

In other news I should probably make friends with older people in business (or make friends with operators in industries with extremely short capital cycles!) 😅

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter