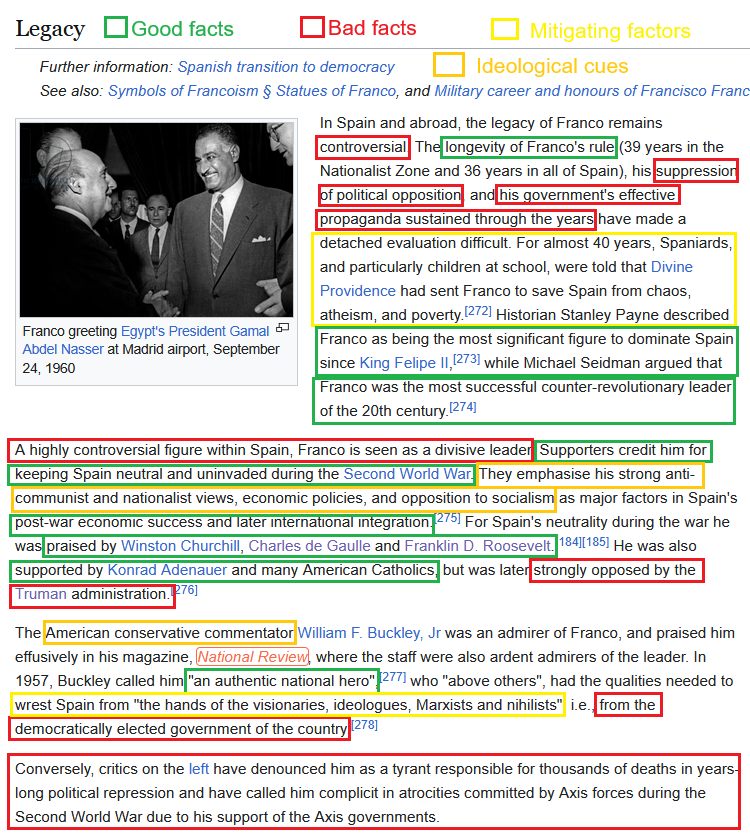

"Berkeley doesn't have affirmative action" is a good example of a technically defensible but straightforwardly false argument that obscures rather than elucidates. As soon as California banned affirmative action, Berkeley openly and urgently looked to circumvent it.

https://twitter.com/Noahpinion/status/1667376986329878529

This is what "no affirmative action" looks like at Berkeley: "comprehensive review" that happens to weight admissions in much the same way explicit affirmative action did.

city-journal.org/article/elites…

city-journal.org/article/elites…

The data is unambiguous, such that there can be no substantive dispute. The affirmative action ban never stopped Berkeley from weighing race heavily within admissions. It just required them to get creative. eml.berkeley.edu/~webfac/morett…

In absolute terms, you saw a small shift in enrollment by race, followed by a return to baseline as the UC system grew more comfortable working around the ban.

UC Berkeley administrators were open about the moral urgency they felt in aiming to circumvent the ban. Their straightforward goal was to re-establish affirmative action while dodging legal action, however they could.

There is an argument to be had over the merits of affirmative action. There is none whatsoever over whether Berkeley has been practicing it since the ban, and the only reasons to claim is hasn't are ignorance or deliberate intent to mislead.

One who had direct experience crafting Berkeley's policy on this has weighed in—don't miss his (excellent) response. As he indicates, part of this comes down to whether implicit, as opposed to explicit, racial preferences constitute affirmative action.

https://twitter.com/dmalcolmcarson/status/1667623623795048448?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh