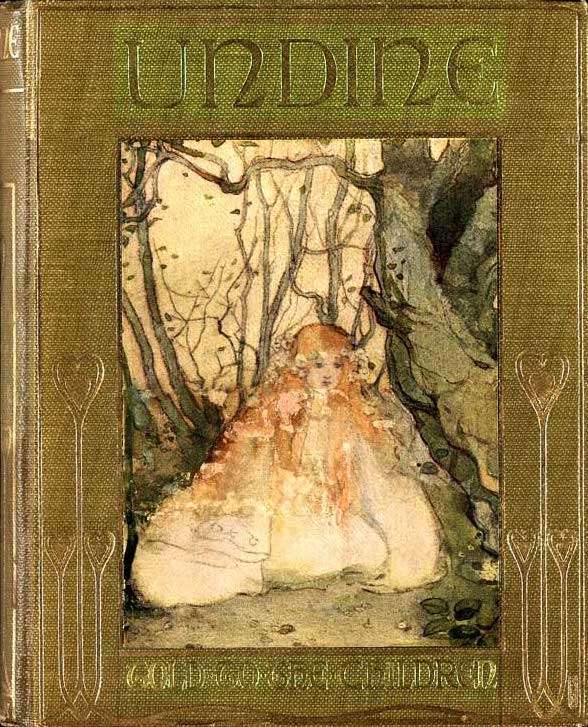

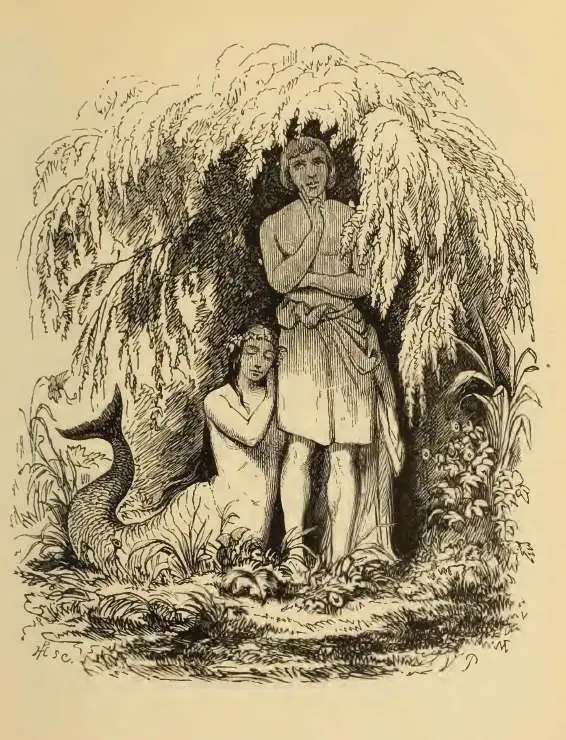

In 1811, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué published a Romantic tale about a mermaid, Undine, who marries a human knight in order to gain an immortal soul. 25 years later, Hans C. Andersen riffed on Undine in composing his far more famous allegory for gay pining, “The Little Mermaid.”

Unrequitedly obsessed with his guardian Edvard (the prince), Andersen (the mermaid) didn’t envision Motte Fouqué's marriage-based happy ending. He said he didn't want to make his mermaid’s salvation dependent on “an alien creature, the love of a human being” (a heterosexual?).

Far from representing her womanly destiny, a marriage between the magically terrestrialized mermaid & the prince is impossible ("unnatural") to the queer Danish raconteur. But I've caught flak for discussing aquatic interspecies romance as queer on this website, so I'll move on.

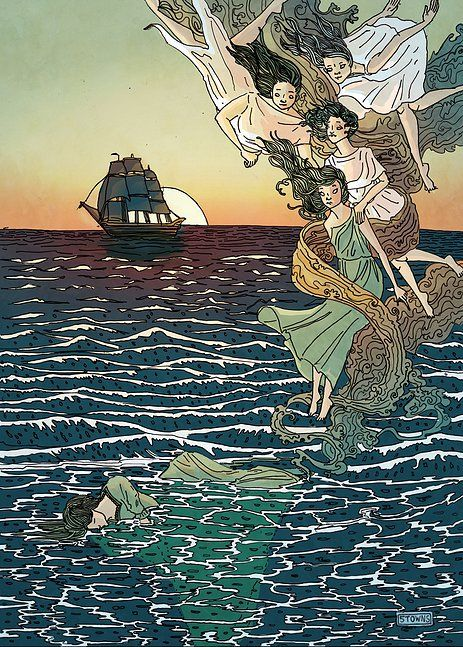

"I have permitted my mermaid," Andersen said, "to follow a more natural, more divine path." What he seemingly meant was that her doomed attempt to gain a soul via hetero courtship incurs many tortures. She ends up, believe it or not, neither in the sea nor on land—but in the air.

The 1837 tale ends with the maid's saintly self-sacrifice. Andersen wants to show that her apparent failure at Love is what creates her real chance at spiritual immortality (God's love) as a "daughter of the air." No happiness on earth for gays (but maybe in the disembodied air?)

Andersen's first draft was titled "Daughters of the Air." Thus, the name “Ariel”—chosen by Disney Studios for their Little Mermaid in 1989—links the redheaded cartoon mermaid both to this ghost, and the aerial sprite on the colonized tropical island in Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

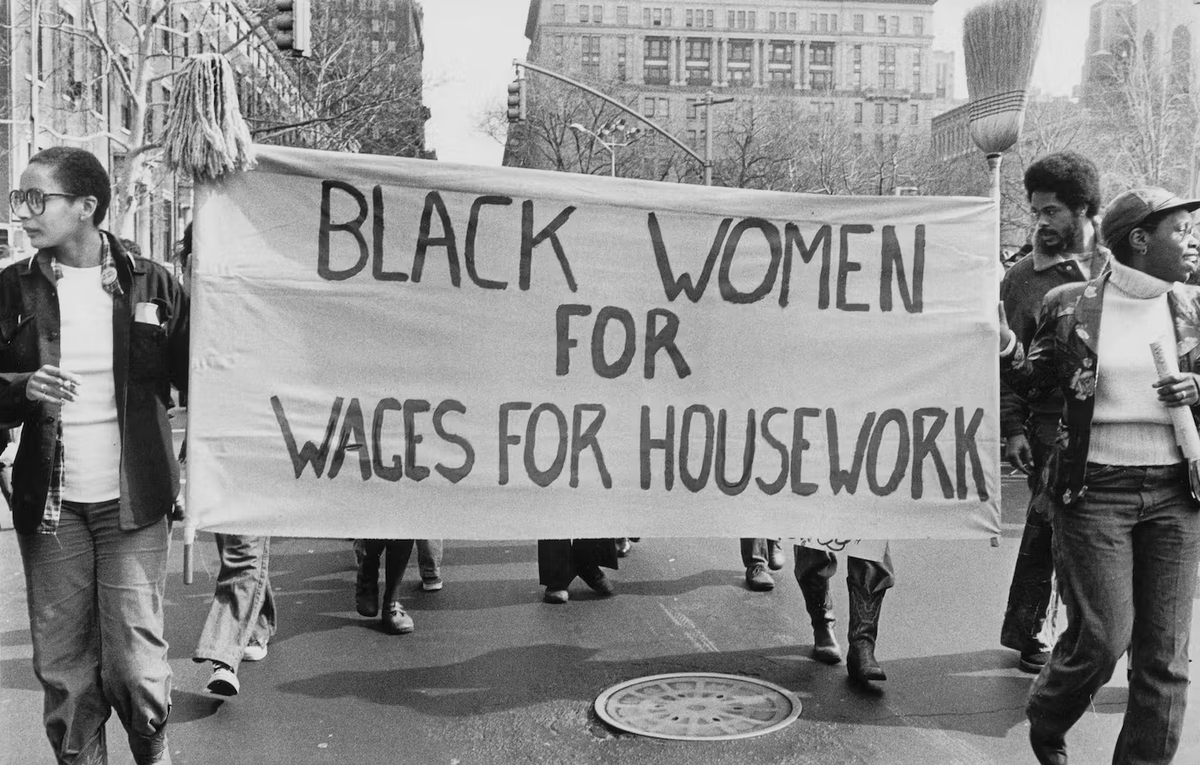

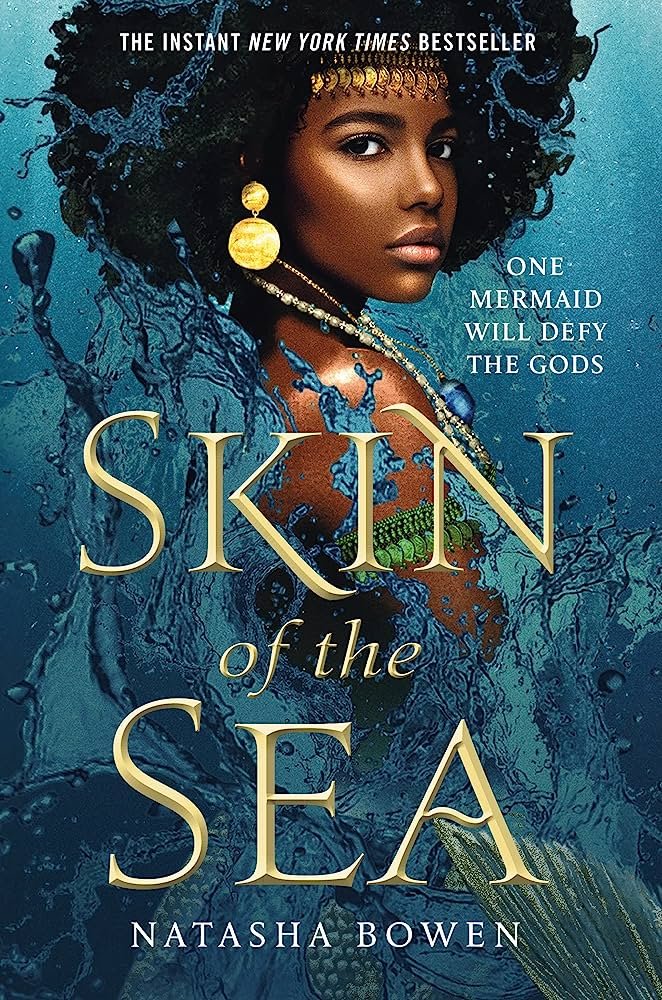

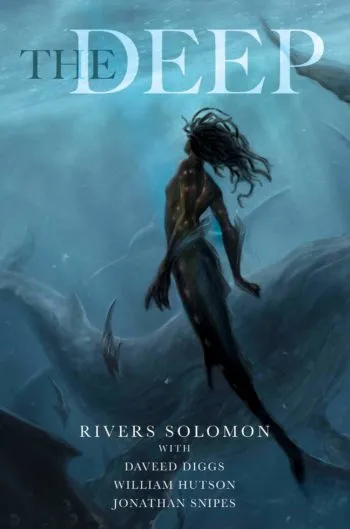

The right's brouhaha defending Ariel's whiteness struck me as particularly perverse given how structurally Black mermaids obviously are, certainly in Caribbean sea where the 1989 Disney movie was set (cf. Drexciya lore, underwater cities peopled by escapees of the Middle Passage)

(as @TraceyBaptiste wrote in a NYT essay about nommos, other ancient Black mermaids, and Mama D’Leau: "The story likely started during chattel slavery, when people were kidnapped ... The mother of the sea came with them because she already existed in West Africa as Mami Wata.")

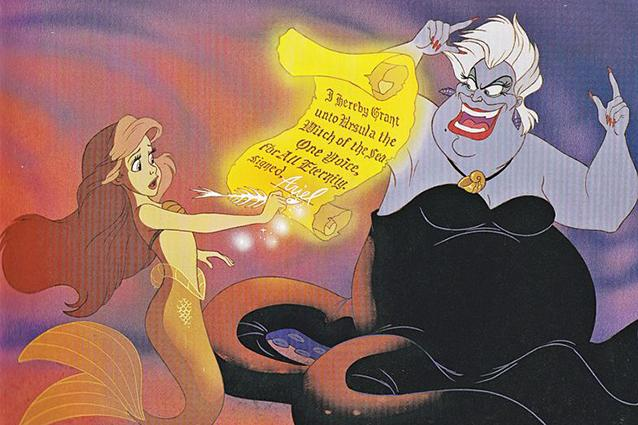

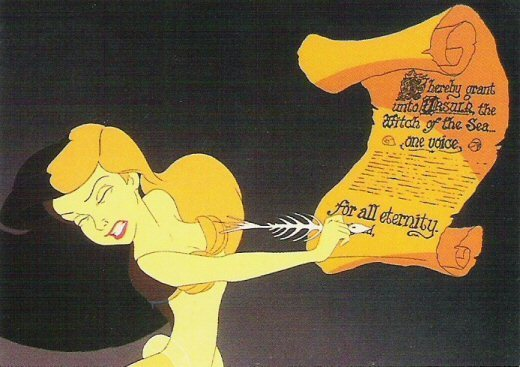

Little Mermaid is about contractuality. In the 2023 version, the stress is on the limits of contract law (Ursula legally should claim Ariel's soul, since they didn't kiss in time - but it's good that she doesn't). It's no accident that black mermaids and queers frame all of this.

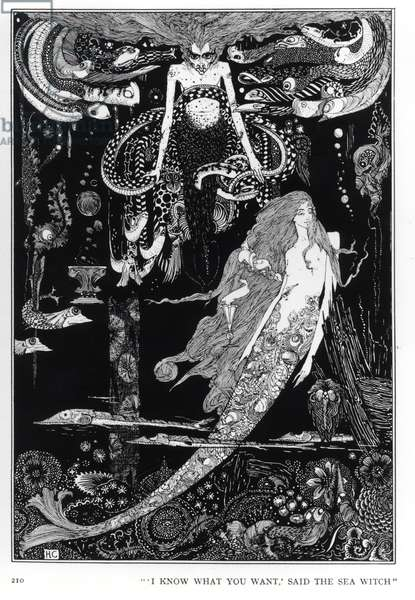

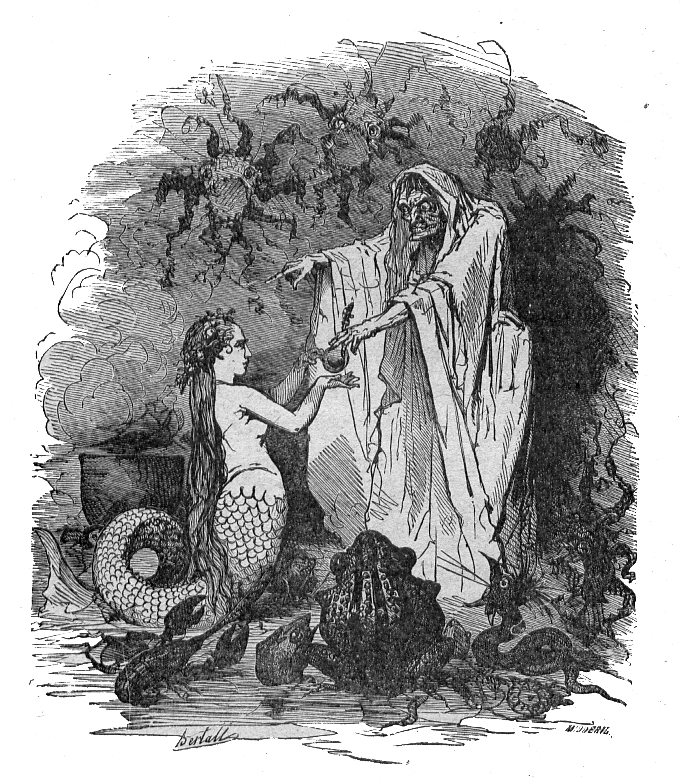

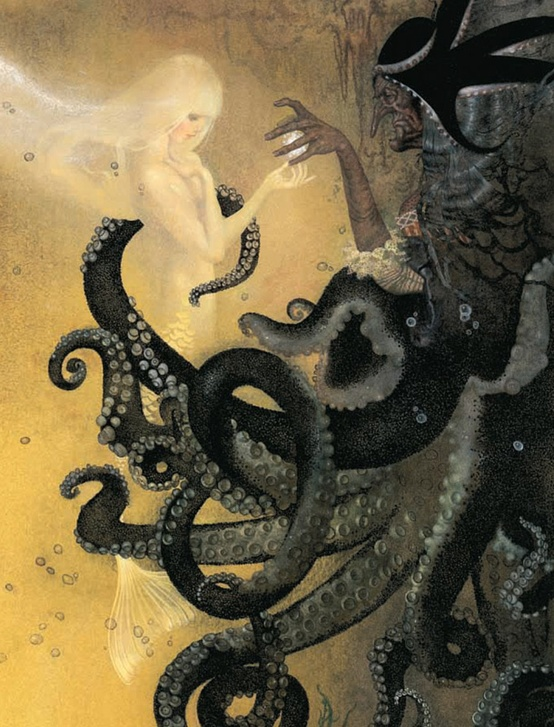

In Andersen, unlike in Disney, the contract holds; the mute heroine simply fails. The prince marries someone else. And to be fair, the sea-witch’s terms were severe! Not only losing a tongue, but metamorphosis feels like being impaled! And if he marries another, she dies!

Andersen wrote a sea witch - the broker of heterosexual contracts - who makes it so every step the mermaid takes while seeking a man's love will feel like thrusting knives. Amazingly, the 2023 Disney remake preserves his quote about this affect of queer doom, as its epigraph...

Whilst the text is (originally) about queer tragedy, though, the subtext about 1989's Ursula, modeled after Divine, is... her joy. BODY LANGUAGE. Burlesque. As Fiona Glenn wrote in her superb love letter to Ursula for @spamzine: "You are not really alone."

spamzine.co.uk/post/essay-sea…

spamzine.co.uk/post/essay-sea…

I'm not saying I liked the 2023 live action. I thought Bailey was great. But since my "queer root" was Ursula, it was somewhat tragic for me that they covered up Melissa McCarthy's arms. The character is based on DIVINE for chrissakes. The godbothering transphobes desexed Ursula!

Anyway, if anyone wants to commission an essay (with decent pay) I'd be delighted. Tl;dr I think Little Mermaid consistently channels these interrelated anxieties: can marriage be gay? can a person be bought? can a queer be happy? should a contract with a matriarch be honored?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh