This 600 year old painting has a hidden secret.

It might seem like an ordinary Renaissance work of art, but look closer — the halo around Mary's head has an inscription written in Arabic.

What does it say? Well, that's where it gets interesting...

It might seem like an ordinary Renaissance work of art, but look closer — the halo around Mary's head has an inscription written in Arabic.

What does it say? Well, that's where it gets interesting...

That version of the Madonna and Child was painted by the influential Florentine artist Masaccio in the 1420s.

The "Arabic" he placed on Mary's halo is gibberish — it's an imitation of Arabic rather than the real thing.

Masaccio did this in many of his other paintings.

The "Arabic" he placed on Mary's halo is gibberish — it's an imitation of Arabic rather than the real thing.

Masaccio did this in many of his other paintings.

But Masaccio's use of pseudo-Arabic (sometimes called pseudo-Kufic) wasn't unusual.

Throughout the Italian Renaissance it was common practice to decorate the halos or robes of Mary and Jesus with this sort of garbled Arabic script.

But... why?

Throughout the Italian Renaissance it was common practice to decorate the halos or robes of Mary and Jesus with this sort of garbled Arabic script.

But... why?

Well, the story begins several centuries earlier.

Because Renaissance "pseudo-Arabic" is far from the only example of elements from Islamic art, architecture, and culture being adopted by Christian Europe...

Because Renaissance "pseudo-Arabic" is far from the only example of elements from Islamic art, architecture, and culture being adopted by Christian Europe...

This coin was minted by King Offa in England during the 8th century. It bears his name alongside an error-strewn Arabic inscription reading:

"Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah."

It was a copy of a gold dinar produced in the Abbasid Caliphate which had made its way to England.

"Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah."

It was a copy of a gold dinar produced in the Abbasid Caliphate which had made its way to England.

The Protestant reformer Martin Luther owned one of the famous "Hedwig Glasses", so-called because they once belonged to a Polish princess called Hedwig.

They were probably originally made in Fatimid Egypt or Syria in the early 12th century, possibly even for Christian patrons.

They were probably originally made in Fatimid Egypt or Syria in the early 12th century, possibly even for Christian patrons.

This robe, which was made in Egypt or Spain and features Arabic inscriptions, once belonged to Thomas à Becket.

Islamic textiles, metalwork, pottery, and glassware were generally of superior quality to those produced in Europe at the same time — and therefore highly prized.

Islamic textiles, metalwork, pottery, and glassware were generally of superior quality to those produced in Europe at the same time — and therefore highly prized.

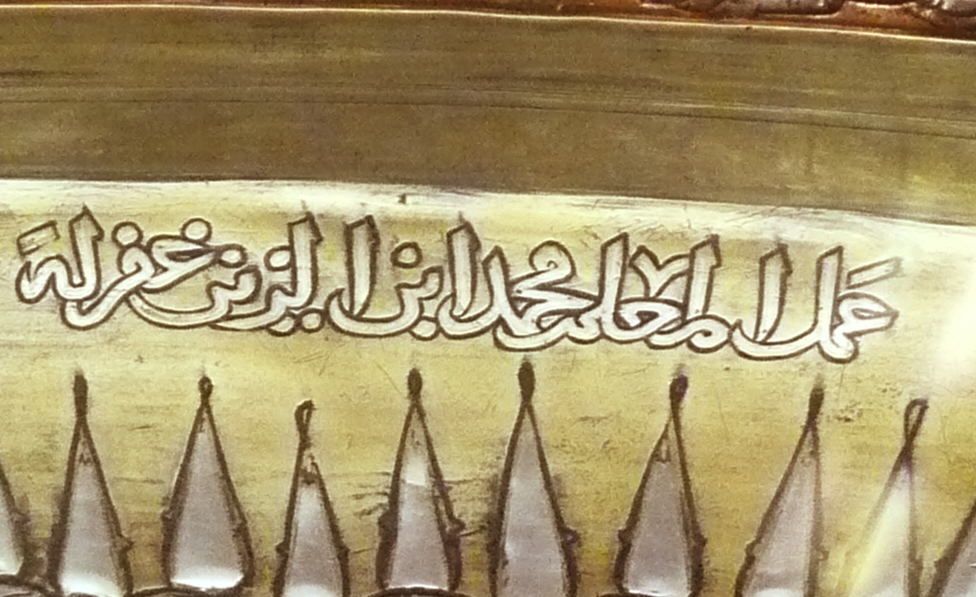

Perhaps the best examples of this — and of the proliferation of Islamic art throughout Medieval Europe more generally — is the Baptistère de Saint Louis.

It is an exquisite piece of metalwork created by the artisan Muhammad ibn al-Zayn in the early 1300s in Mamluk Egypt.

It is an exquisite piece of metalwork created by the artisan Muhammad ibn al-Zayn in the early 1300s in Mamluk Egypt.

Made from brass and inlaid with gold and silver, it portrays an incredibly complex, unbroken scene of princes hunting and fighting, alongside exotic animals and floral decoration.

It ended up in France and was used to baptise members of the French royal family until 1856.

It ended up in France and was used to baptise members of the French royal family until 1856.

An object almost certainly made by Islamic artisans for Christian patrons is this brass pilgrim flask, probably made in Syria in the 13th century.

It mixes Christian scenes (the Madonna and Child, the Nativity etc.) with Islamic decoration and Kufic/naskhi inscriptions.

It mixes Christian scenes (the Madonna and Child, the Nativity etc.) with Islamic decoration and Kufic/naskhi inscriptions.

Or there's the Griffin of Pisa, a stylised bronze beast covered in arabesque engraving and Kufic inscriptions, created in Al-Andalus (Muslim-ruled Spain) during the 11th century.

For several hundred years it stood atop Pisa Cathedral in Italy; a replica has now taken its place.

For several hundred years it stood atop Pisa Cathedral in Italy; a replica has now taken its place.

But this is about more than trade; there was also direct influence.

In Spain, which had been ruled wholly or partly by Islamic dynasties for centuries, Christian art and architecture were heavily influenced by their Islamic equivalents.

This is known as the "Mudéjar" style.

In Spain, which had been ruled wholly or partly by Islamic dynasties for centuries, Christian art and architecture were heavily influenced by their Islamic equivalents.

This is known as the "Mudéjar" style.

A good example is the ceiling of the Royal Convent of Santa Clara in Tordesillas, built during the 14th century, with its interlocking, geometric design.

Muqarnas, horseshoe arches, calligraphic and floral ornamentation: these, and more, were borrowed from Islamic architecture.

Muqarnas, horseshoe arches, calligraphic and floral ornamentation: these, and more, were borrowed from Islamic architecture.

But the influence of Islamic architecture on Christian Europe was not limited to Spain and Portugal.

Many believe the pointed arch — one of the defining features of Gothic architecture — was introduced to Europe from the Middle East, perhaps by returning Crusaders.

Many believe the pointed arch — one of the defining features of Gothic architecture — was introduced to Europe from the Middle East, perhaps by returning Crusaders.

Specific decorative motifs were also adopted and many Gothic churches bear architectural elements directly borrowed from Islamic art, as at Le Puy Cathedral in France.

And the Gothic trefoil arch may have its ultimate origins in 8th century Umayyad architecture in Syria.

And the Gothic trefoil arch may have its ultimate origins in 8th century Umayyad architecture in Syria.

This was not all one way.

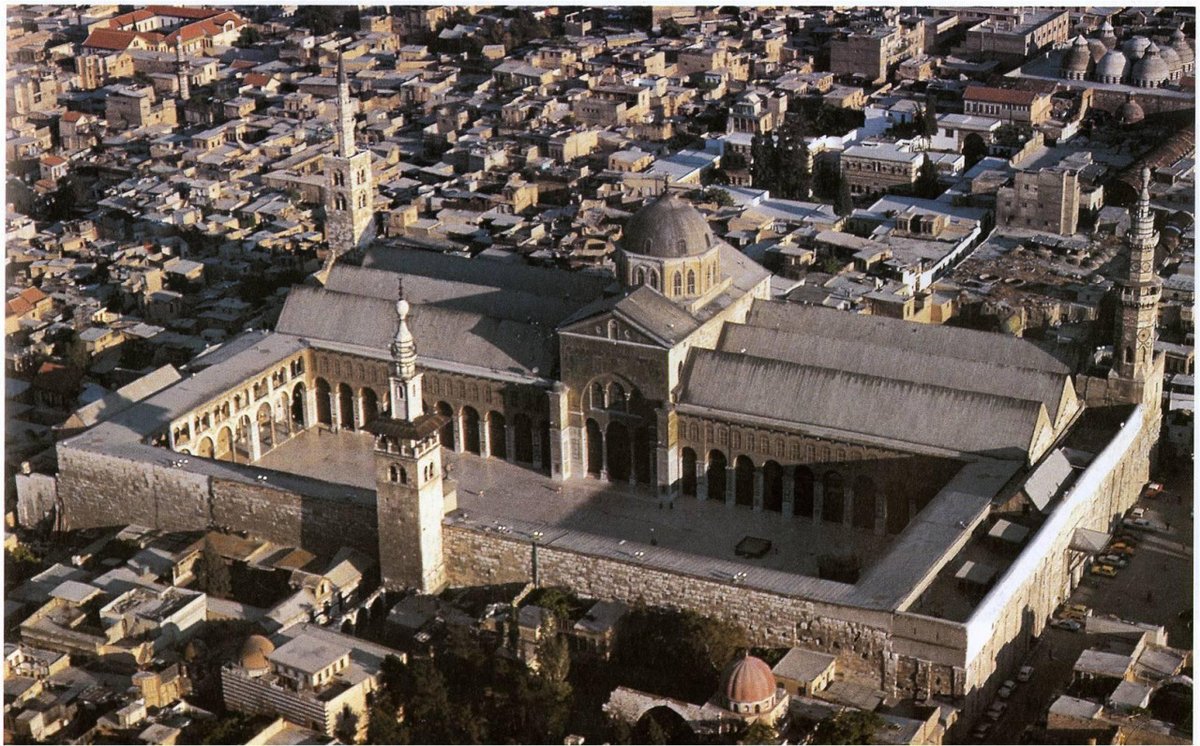

The influence of Classical and Byzantine architecture on early Islamic buildings, like the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, is just one example of what was a mutual (though not equal) influence.

But that's a story for another day.

The influence of Classical and Byzantine architecture on early Islamic buildings, like the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, is just one example of what was a mutual (though not equal) influence.

But that's a story for another day.

There is one place in particular which sums all this up: the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily.

It was built during the 12th century and somehow combines Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic architecture into one extraordinary building.

At the Mediterranean cultural crosswinds.

It was built during the 12th century and somehow combines Norman, Byzantine, and Islamic architecture into one extraordinary building.

At the Mediterranean cultural crosswinds.

Which brings us back to Italy, then, and to the use of pseudo-Arabic decoration in Renaissance art.

Why did they do it?

Some have speculated that artists imitated Arabic to evoke the atmosphere of the Holy Land (i.e. where Mary was from), which was then under Islamic rule.

Why did they do it?

Some have speculated that artists imitated Arabic to evoke the atmosphere of the Holy Land (i.e. where Mary was from), which was then under Islamic rule.

Or, perhaps, it was simply because of the aesthetic qualities of Arabic script and its suitability for decoration.

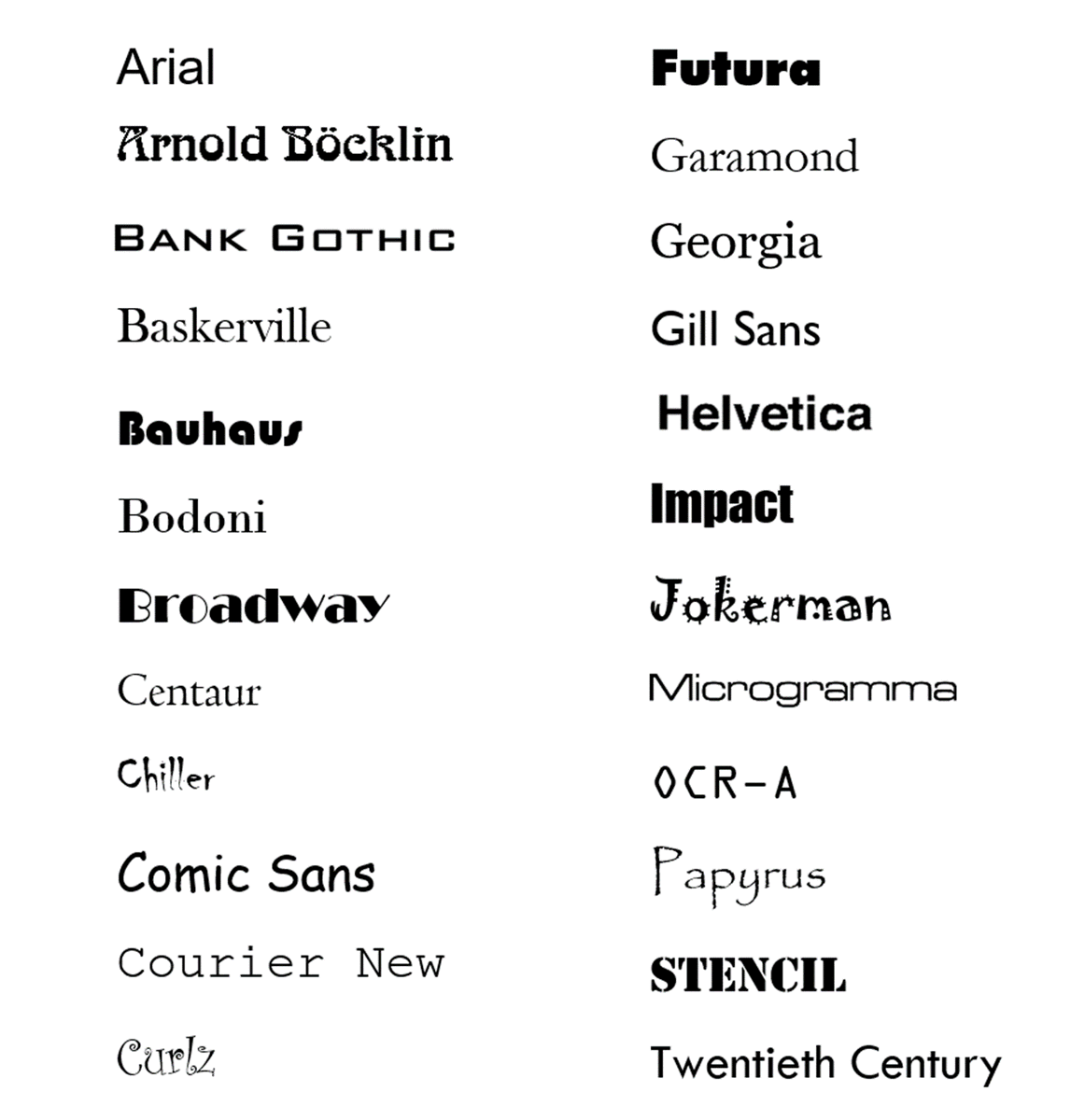

In Islamic art, more so than in any other artistic tradition in the world, writing itself was a form of art, whether used in metals, ceramics, ivories, or books...

In Islamic art, more so than in any other artistic tradition in the world, writing itself was a form of art, whether used in metals, ceramics, ivories, or books...

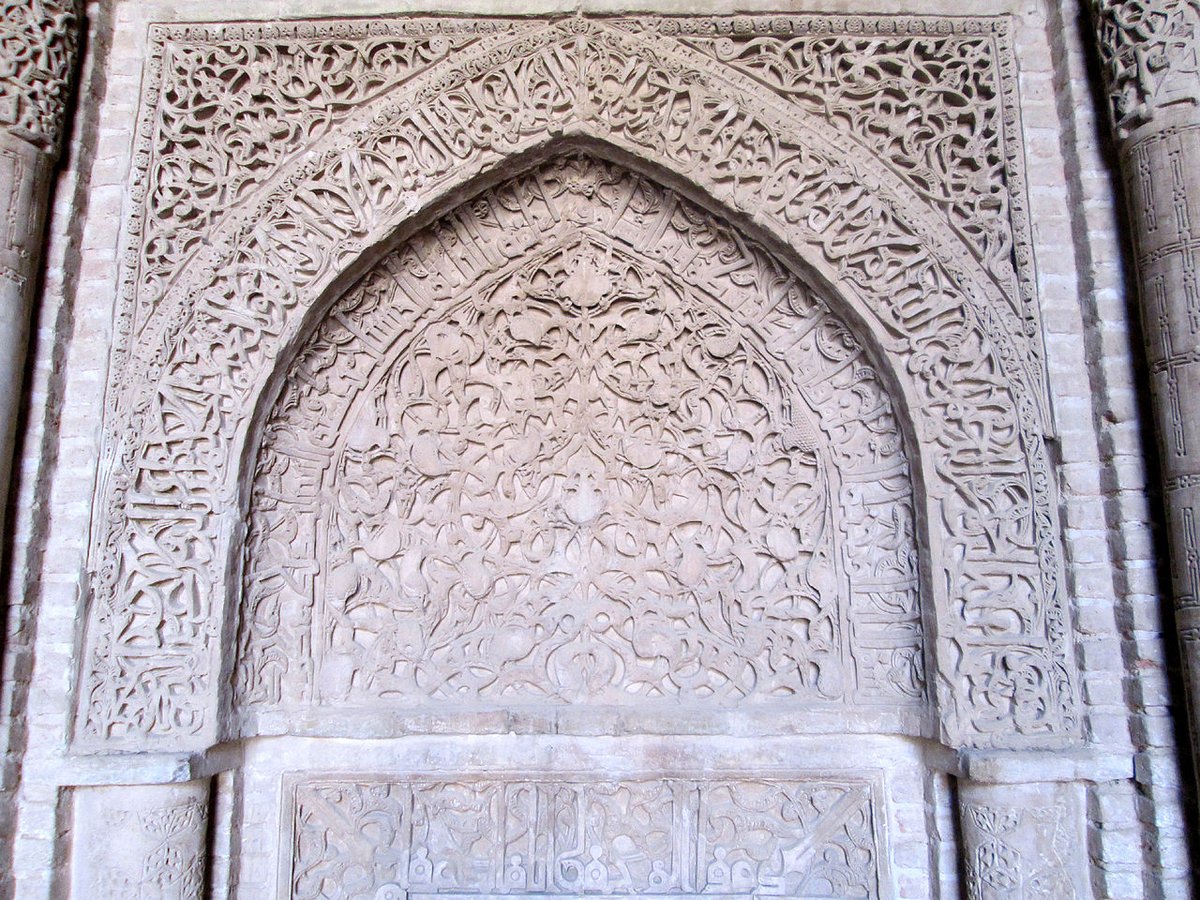

Using Kufic, Naskhi, or Thuluth — all calligraphic variants of Arabic — the written word was an infinitely malleable artistic medium.

Calligraphic ornamentation even became an important part of architecture, where words were blended into and among abstract decoration.

Calligraphic ornamentation even became an important part of architecture, where words were blended into and among abstract decoration.

This Madonna's halo bears a striking resemblance to metal dishes created in Mamluk Egypt; notice how the bands of script are separated by rosettes or roundels.

Such luxury items, as we have seen, were common in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Was this Da Fabriano's inspiration?

Such luxury items, as we have seen, were common in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Was this Da Fabriano's inspiration?

The psuedo-Arabic used by Masaccio to decorate his painting doesn't say anything itself.

But the fact he used this imitation of Arabic calligraphy says a lot about the immense influence of Islamic art and architecture on Medieval Europe.

The stories art can tell...

But the fact he used this imitation of Arabic calligraphy says a lot about the immense influence of Islamic art and architecture on Medieval Europe.

The stories art can tell...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter