Katie's excellent post here is getting a lot of people either purposefully or ignorantly misunderstanding the point. At the risk of over-explaining, I'm going to go through this. /1

https://twitter.com/katiedimartin/status/1670141121983307777

First of all, a horse is not a chair. Everyone agrees on this. No one is arguing that a horse is actually a kind of a chair. That's the point. /2

Katie is demonstrating that the definition of "chair" provided inadvertently includes horses. This doesn't tell us anything about the meaning of "chair", but it tells us that the definition provided does not adequately reflect our knowledge of the meaning of the word. /3

This is a version of the mathematical technique of proof by contradiction. You start with a premise, follow it to its conclusion, and if the conclusion doesn't match what we know (if it contradicts something), then we can reject the premise. /4

This also doesn't mean that words have no meaning and that "chair" is meaningless. It's fairly self-evident that "chair" has a meaning, and that we use that meaning successfully in communication. But capturing that meaning in a plain language definition may be challenging. /5

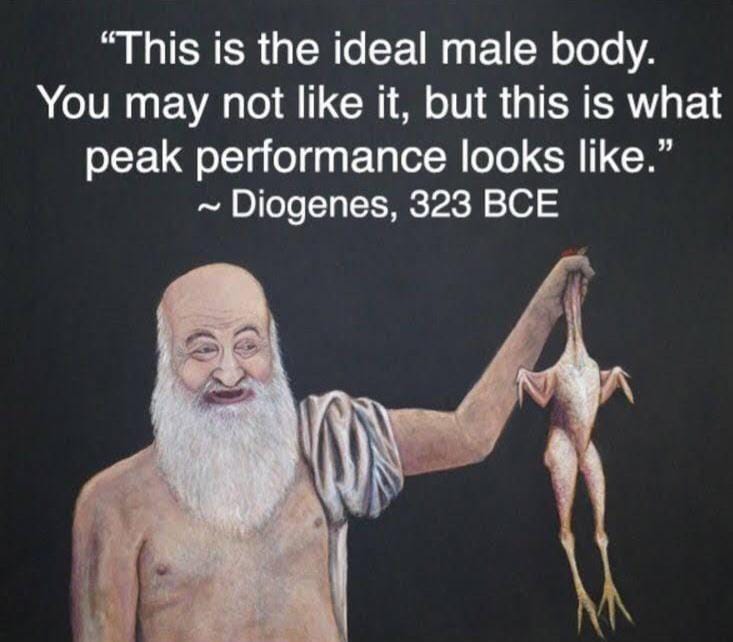

This is not a "leftist" or "postmodern" argument. This is pretty basic philosophy. There's an old story where Plato defines a human to be a "featherless biped"; Diogenes shows up with a plucked chicken declaring "behold! a man!" /6

More recently, Wittgenstein asked what a "game" is. Is there something all games have in common? Some games (football, basketball) involve physical activity, but not all (go, poker). Some games are competitive (Fortnite, cricket), but some are not (escape rooms, solitaire). /7

Some games have complex rules (tennis, Settlers of Catan), some do not (tag, calvinball). Some games require skill (chess), some do not (snakes and ladders). /8

What's more, there are things which have some attributes of games, such as being competitive, or team-based, or pleasurable, but are not (typically) games. (E.g. stock market trading, barn-raising, and sex, respectively.) /9

Wittgenstein concluded that there is not a single characteristic that is common to all games, but that there is still a coherent concept of a "game". There's no snappy one-sentence summary but it's still a meaningful idea. /10

Some commenters have connected Katie's remarks to trans rights - often via the question "what is a woman?" Being unable to provide a single snappy answer to the question is actually the normal state of affairs, given how hard it is to define categories. /11

This line of reasoning isn't pro-trans or anti-trans, but is simply pro-logic. It's a logical fallacy to argue against trans rights on the basis of "not being able to define 'woman'". That argument would lead you to opposing all sorts of things that we can't define easily. /12

If you want to argue with strangers on the internet, fine, it's your life, but please think about your arguments and conceptual foundations beforehand. /13

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter