Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, in the suburbs of New York, in 1882. At the age of 31 he moved to Manhattan and lived there until his death in 1967.

He was, then, a New Yorker through and through.

He was, then, a New Yorker through and through.

Hopper was destined to be an artist of some sort; this is his earliest dated drawing, from when he was just eleven.

For six years, starting in 1900, he studied at the New York School of Art and Design under several of America's leading artists.

For six years, starting in 1900, he studied at the New York School of Art and Design under several of America's leading artists.

One of them was William Merritt Chase, an American Impressionist under the spell of the French painters who had been revolutionising art since the 1870s, such as Monet, Manet, Renoir, and Degas.

One of thousands of Impressionist imitators across Europe and America.

One of thousands of Impressionist imitators across Europe and America.

Another teacher was Robert Henri, the leader of the so-called "Ash Can School".

He was a former Impressionist reacting against both Impressionism and the state of American art more generally.

A would-be rebel, then.

He was a former Impressionist reacting against both Impressionism and the state of American art more generally.

A would-be rebel, then.

Henri and his Ash Can School (along with several of his students, such as the brilliant George Bellows) wanted to bring American art closer to the realities of every day life.

It was a movement aiming for Realism, then, though it never quite cast off its Impressionist origins.

It was a movement aiming for Realism, then, though it never quite cast off its Impressionist origins.

After finishing his studies in 1906 Hopper went to Paris three times, about which he said in 1910:

"It seemed awful crude and raw here [in the US] when I got back. It took me ten years to get over Europe."

In Paris Hopper was initially inspired by artists like Degas and Manet.

"It seemed awful crude and raw here [in the US] when I got back. It took me ten years to get over Europe."

In Paris Hopper was initially inspired by artists like Degas and Manet.

But anybody familiar with Hopper's work will know there's more going on than a reinterpretation of Impressionism, and that's right.

His favourite European painter was Rembrandt; Hopper said Rembrandt's famous Night Watch was the greatest painting he'd ever seen.

His favourite European painter was Rembrandt; Hopper said Rembrandt's famous Night Watch was the greatest painting he'd ever seen.

Hopper also adored a colourblind engraver called Charles Meryon, known for his depictions of Paris.

It was the dark tones of Rembrandt and the realistic but emotionally charged architecture of Meryon (rather than the bright colours of Impressionism) that inspired Hopper most.

It was the dark tones of Rembrandt and the realistic but emotionally charged architecture of Meryon (rather than the bright colours of Impressionism) that inspired Hopper most.

But upon returning to New York Hopper's career did not go as planned. He had to work as a freelance illustrator:

"I kept some time to do my own work. Illustrating was a depressing experience. And I didn't get very good prices because I didn't often do what they wanted."

"I kept some time to do my own work. Illustrating was a depressing experience. And I didn't get very good prices because I didn't often do what they wanted."

Well, even if he hated this work, whether illustrating magazines, making movie posters, or designing adverts, he was very good at it.

And, in his spare time, Hopper started making etchings; here we see the birth of the style for which he is now so famous.

And, in his spare time, Hopper started making etchings; here we see the birth of the style for which he is now so famous.

Eventually his fortunes changed. Hopper married the artist Josephine Nivison in 1924 and soon received the belated recognition he deserved.

Galleries bought and exhibited his paintings and, by the 1930s, Hopper had become a respected, established, and financially secure artist.

Galleries bought and exhibited his paintings and, by the 1930s, Hopper had become a respected, established, and financially secure artist.

But Hopper — a quiet man, reserved, wistful, meticulous — was not enthralled by success or fame. As he later said: "Recognition does not mean so much, you never get it when you need it."

He even turned away from the brighter colours of his early successes, like Mansard Roof...

He even turned away from the brighter colours of his early successes, like Mansard Roof...

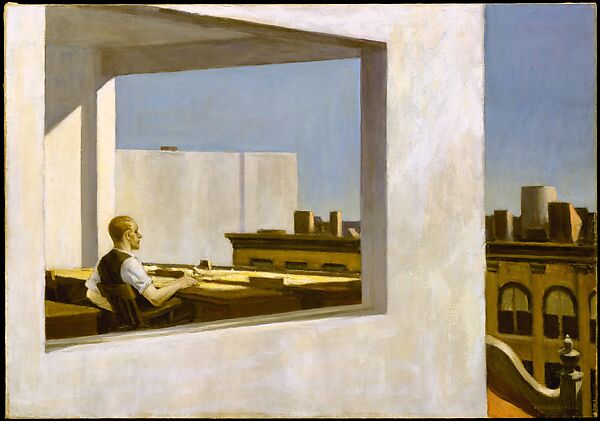

...and Hopper did what his rebellious mentor Robert Henri could not — shake off French Impressionism entirely.

Here was not a European import, but a uniquely American artist.

The liveliness of impressionism was gone, replaced by a still, strange, geometric, urban solitude.

Here was not a European import, but a uniquely American artist.

The liveliness of impressionism was gone, replaced by a still, strange, geometric, urban solitude.

There are traces of influence — Rembrandt's chiaroscuro must have affected Hopper's scrupulous attention to light, and Meryon's precise-but-dramatic engravings of Parisian architecture clearly shaped Hopper's attention to American architecture.

These are, however, only traces.

These are, however, only traces.

And in something like Early Sunday Morning (1930), which might even be his best painting, any such influences have been wholly subsumed by Hopper's full artistic maturity.

He found a style in the 1920s and stuck to it, with some gradual refinement, for the rest of his life.

He found a style in the 1920s and stuck to it, with some gradual refinement, for the rest of his life.

Whereas Henri and his circle had been outdone by Picasso and his Cubists in Paris, who were more outrageously avant-garde than Henri could ever hope to be, Hopper was, as he said himself, simply uninterested by Picasso.

Hopper had his own way of doing things.

Hopper had his own way of doing things.

Henri wanted to be a revolutionary and Chase wanted to be an Impressionist. Hopper was free of such anxieties:

"We are not French and never can be, and any attempt to be so is to deny our inheritance."

Hopper painted as the man he was: a New Yorker born and raised.

"We are not French and never can be, and any attempt to be so is to deny our inheritance."

Hopper painted as the man he was: a New Yorker born and raised.

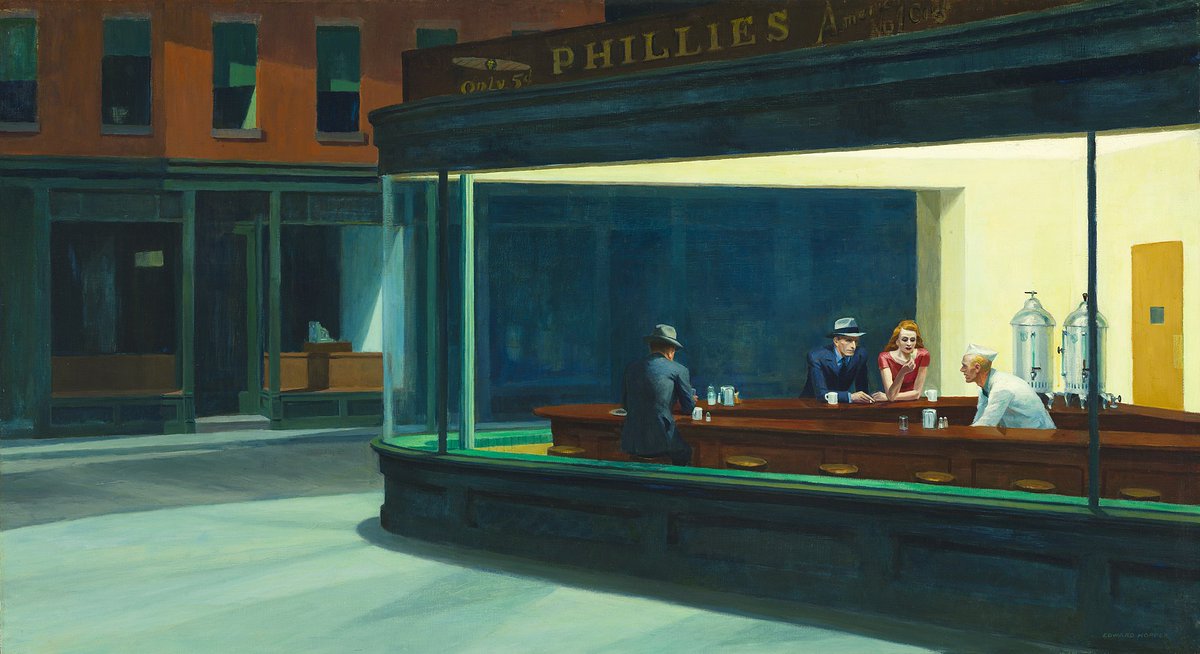

The modern metropolis was created in America and it was Hopper who captured that in art.

But rather than the glamour and action of the 1920s evoked by other artists, Hopper turned to domestic scenes glimpsed through windows at night and lonely figures lost in the cityscape.

But rather than the glamour and action of the 1920s evoked by other artists, Hopper turned to domestic scenes glimpsed through windows at night and lonely figures lost in the cityscape.

If Grant Wood was the definitive artist of rural America in the early 20th century, then Hopper was his urban equivalent (though Hopper was also a fine rural painter).

Both of them wrestled with European artistic influence; both successfully shook it off.

Both of them wrestled with European artistic influence; both successfully shook it off.

Hopper's command of light and space, his simple but striking architecture, and the absolute clarity of his scenes, usually reduced to a few simple elements and a handful of solitary figures... it is an art which, though clearly fixed in the 20th century, feels timeless.

Vincent van Gogh's Cafe Terrace at Night was on show in New York in 1942, the same year Hopper painted Nighthawks.

It must have inspired him, but everything has been reimagined; Hopper was an artistic school of one. As he said:

"The only real influence I have had was myself."

It must have inspired him, but everything has been reimagined; Hopper was an artistic school of one. As he said:

"The only real influence I have had was myself."

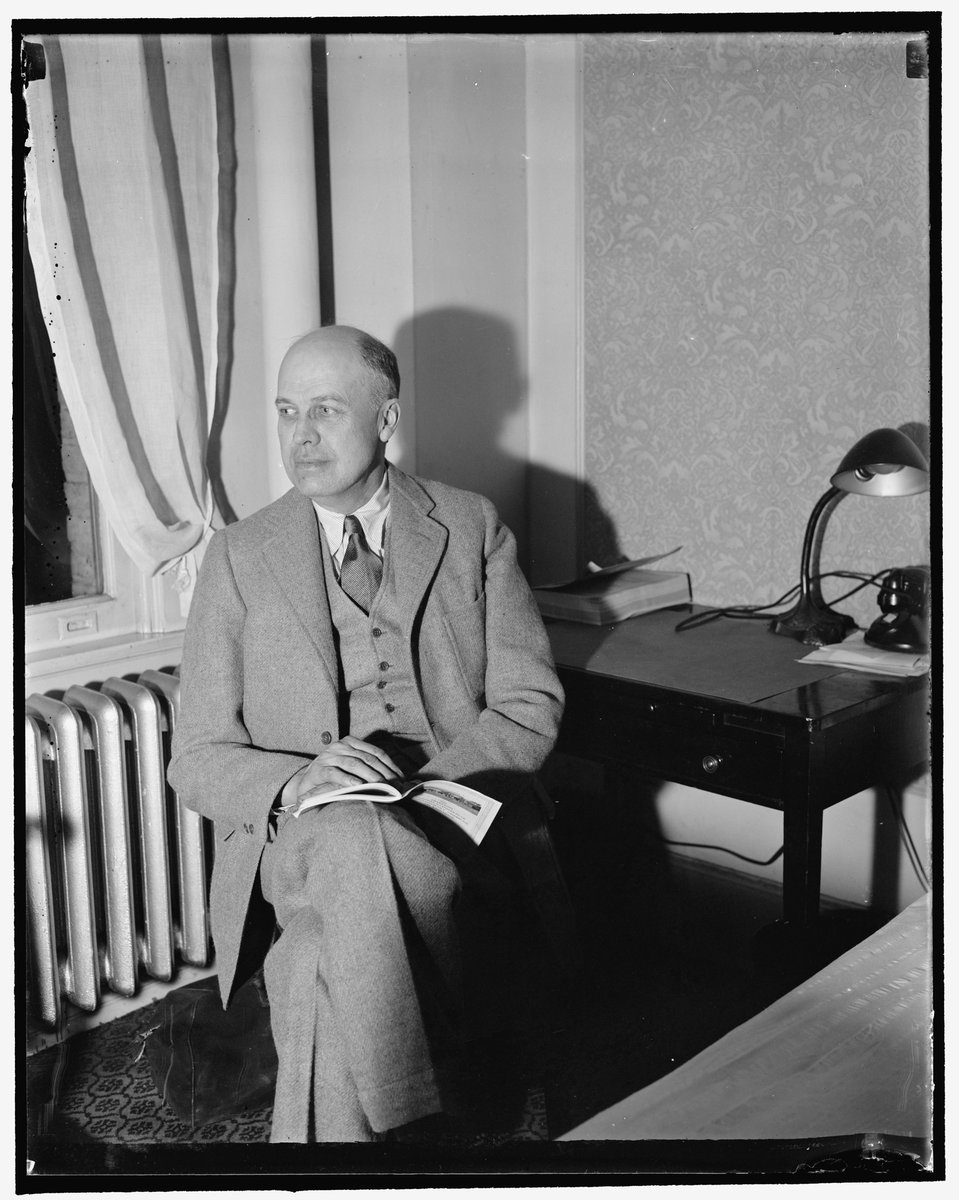

Who is the greatest ever American artist? Copley, Church, Whistler, Sargent, O'Keeffe, Wood, Rothko, and Basquiat are only some of the many potential answers.

But Hopper — pictured here as though a solitary figure in one of his own paintings — might just be the best of them all.

But Hopper — pictured here as though a solitary figure in one of his own paintings — might just be the best of them all.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh