So a loyal servant of an autocratic ruler turned his army around and marched on Paris, but the plan failed in the end and now he's either a wanted fugitive or is being nudged into exile?

That's right, it's the story of Michel Ney! THREAD:

That's right, it's the story of Michel Ney! THREAD:

2/ Michel Ney was one of Napoleon's marshals, an aggressive soldier dubbed "the bravest of the brave" for his gritty rearguard action during Napoleon's infamous retreat from Moscow.

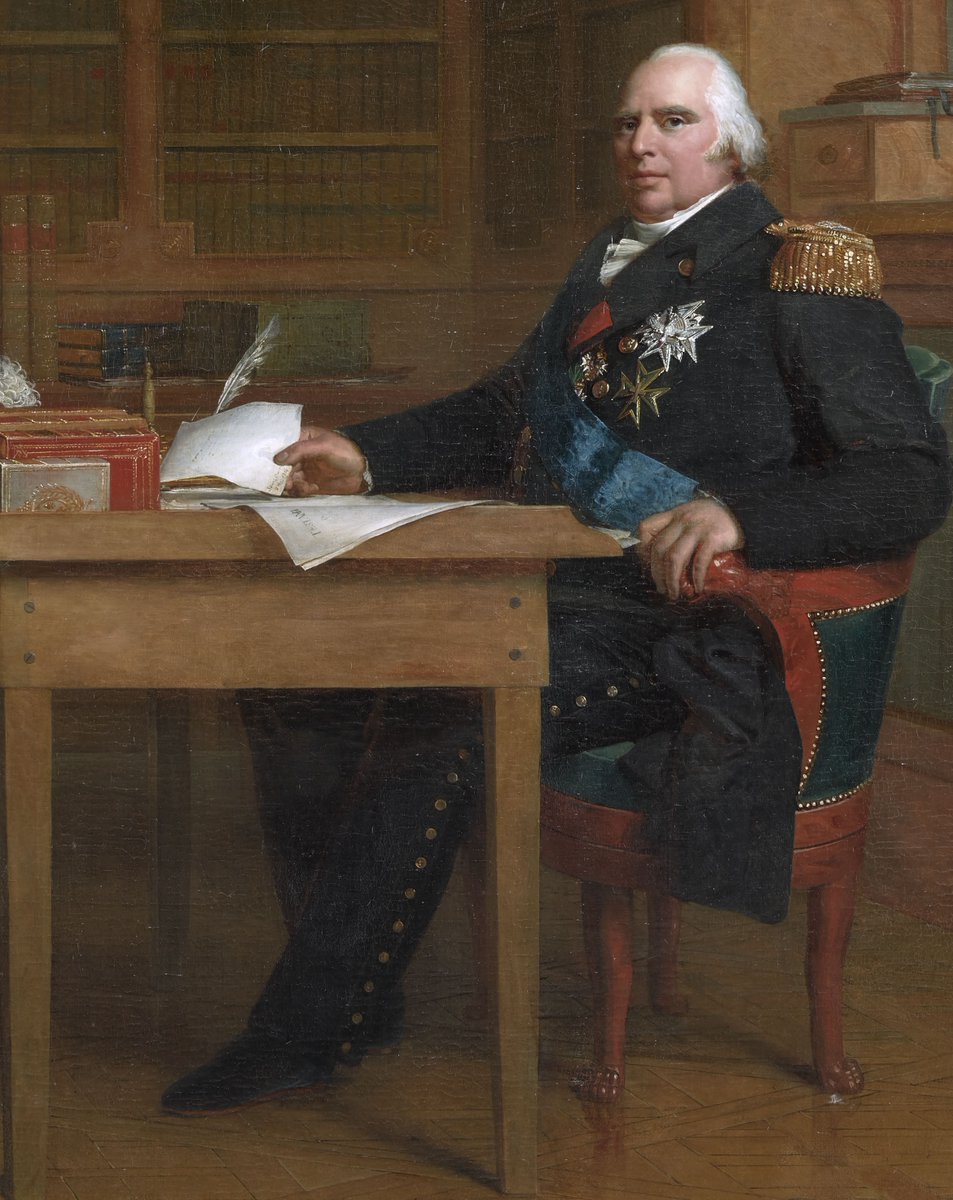

3/ But when Napoleon abdicated in 1814, Ney — like most of Napoleon's marshals — swore allegiance to King Louis XVIII.

It was an awkward time. France was at peace, never ideal for a career soldier like Ney. And the new regime he served had... issues.

It was an awkward time. France was at peace, never ideal for a career soldier like Ney. And the new regime he served had... issues.

4/ The proud imperial army Ney had helped lead was gutted, with many officers forcibly retired. As these good soldiers were sent home, new officers were appointed to replace them: royalist émigrés who often hadn't fought in decades — or who had fought, but AGAINST France.

5/ Meanwhile, the old-style nobles in Louis XVIII's court looked down on Imperial generals like Ney — the son of a provincial cooper, elevated to Duke of Elchingen & Prince of the Moskva — as parvenus.

Ney's wife Aglaé (🖼️) was supposedly bullied into tears by court ladies.

Ney's wife Aglaé (🖼️) was supposedly bullied into tears by court ladies.

6/ Then, in spring 1815, Napoleon escaped his minimum-security exile in the nearby island of Elba and landed in Provence, marching toward Paris. The emperor had only a small force, but regime forces offered no resistance, and many switched sides. (Sound familiar?)

7/ Whatever his misgivings, Ney reaffirmed his loyalty to Louis XVIII when news of Napoleon's landing arrived. He offered his services to hunt down Napoleon, and infamous swore to bring the emperor back "in an iron cage."

8/ Emotional and hot-tempered, Ney ranted against his old boss: "It's a good thing the Man from Elba has attempted this crazy enterprise. It's going to be the last act of his tragedy. I'll fix Bonaparte. We're going to attack the wild beast."

9/ But easier said than done. When Ney arrives to take command, his soldiers are strung out across the frontier. He has no artillery and no formal orders. Most worryingly of all, one of his colonels tells Ney that their men cannot be relied upon to fight their former emperor.

10/ Michel Ney, dauntless, orders the ~7,000 men he does have to advance south, preparing to meet Napoleon. But he gets a report: Napoleon "left Lyons with 5,000 men, but the 76th Line has jsut defected; probably other units too. By now he can't have less than 12,000 men."

11/ Ney's troops continue to act mutinously. He imprisons an officer for shouting "Vive l'Empéreur!" He declares that "the first soldier that budges, I'll pass my sabre through his guts!" But Ney is beginning to waver.

12/ When a royalist officer insists, "I'm in the King's service, and... I have my honor!" Ney snaps: "I, too have my honor! That's why I don't like being humiliated... It's obvious the King doesn't want any part of us."

13/ Soon, Ney addresses his troops. His officers have no clue what's coming: Upon hearing Ney declare "'the cause of the Bourbons is lost forever,' I expected him to add 'unless you stand by me,'" one recalled. Instead? "Only the Emperor Napoleon... has the right to reign."

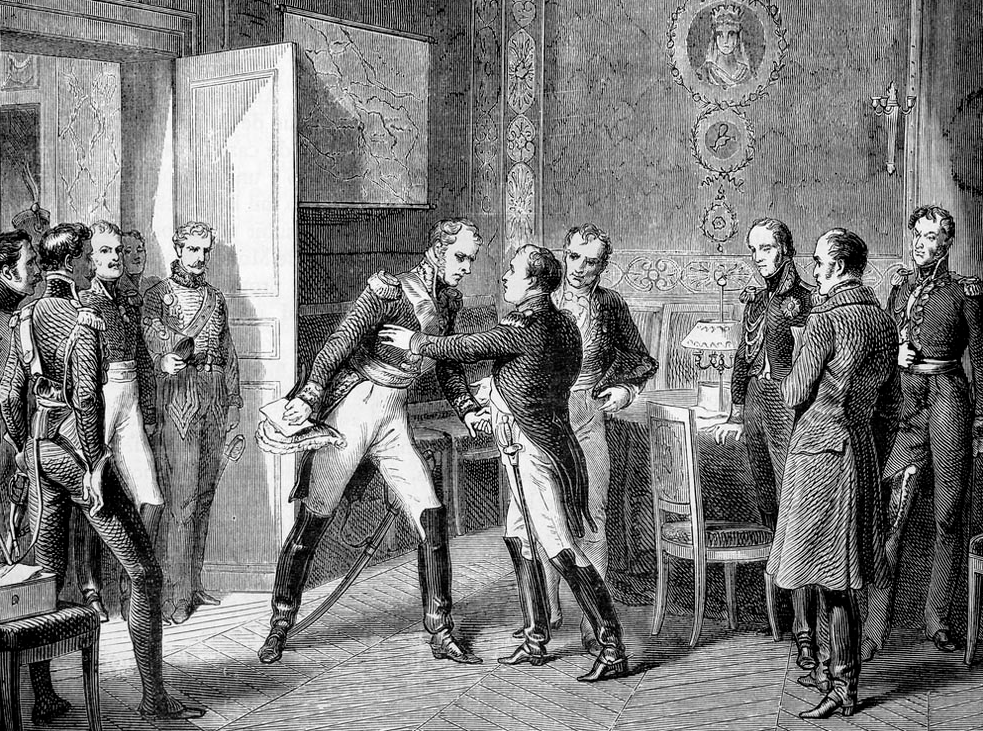

14/ The soldiers go with Ney over to Napoleon's cause en masse. His officers largely refuse and ride off. Despite fears Napoleon would be angry at Ney for his role pressuring him to abdicate the year before, Napoleon calls for an embrace: "I've no need... of explanations."

15/ We fast forward a few months to the field of Waterloo. Ney commands the left wing of the French army. It's not one of Ney's best military showings, but he remains brave, leading a stupendous-but-futile mass cavalry charge:

16/ In the aftermath of Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon's regime falls apart quickly. Ney's fellow marshal, the indomitable Davout (unwisely left behind from Waterloo) tries to organize a defense of Paris. Ney puts his affairs in order and prepares to escape.

17/ The man of the hour is Joseph Fouché, an unscrupulous political survivor who rapid-fire betrayals have ended up with him serving the restored Bourbons. Fouché's job is to hunt down traitors — but not TOO vigorously.

18/ Louis XVIII announces an amnesty for rebellious acts during the Hundred Days (sound familiar?) — with a few exceptions. When the list of exceptions is finalized, Michel Ney's name is #1 on the list. He is wanted for treason.

19/ BUT at the same time as Fouché is putting Ney on the list of wanted traitors, he ALSO gives him two passports — one under a fake name — to help Ney slip out of the country. It was much nicer to just let troublemakers slip into exile, and save the trouble of killing them!

20/ And indeed most of the proscribed Bonapartists make their escape, as intended. Ney, however, was not one of them. In a decision that bewilders people to this day, Ney instead spends a month wandering around the Massif Central highlands until police finally tracked him down.

21/ An exasperated Louis XVIII is alleged to have said, upon hearing of Ney’s arrest, “He is doing us more harm by letting us catch him than he did when he betrayed us.”

But Ney is too infamous to be let off now. The regime has to put him on trial.

But Ney is too infamous to be let off now. The regime has to put him on trial.

22/ Ney ended up on trial for treason in front of the Chamber of Peers (i.e., House of Lords). That was a foregone conclusion: Ney is convicted of treason, one vote short of unanimous. 139 Peers vote for death, just 17 for exile.

23/ At this point, Louis could have pardoned Ney. Many historians say he should have. But there was an intense push for vengeance from royalist courtiers, and pressure from the Allied armies occupying France for Louis to show firmness. He refuses to pardon Ney.

24/ Ney's final words were supposedly: "I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her," and giving the firing squad the order to shoot.

25/ From his final exile on St. Helena, Napoleon supposedly said: "With respect to physical courage, it was impossible for [Joachim] Murat and Ney not to be brave, but no men ever possessed less judgment..."

26/ France's prime minister, the Duc de Richelieu — previously, in his exile, the well-regarded Russian governor of Odesa — pushed for Ney's death, but then tried to use him as a scapegoat to tamp down royalist cries for widespread vengeance. This had mixed success.

27/27 And if you want to know more... then you should listen to The Siècle! Episode 1 kicks off in 1814, and tells the story of this tumultuous time in French history beat by beat!

https://twitter.com/TheSiecle/status/1137742085971488768?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh