This is a real place.

It's a village in the Netherlands called Bourtange (population: 430) built in and around an 18th century star fort.

How and why does it exist? That's where things get interesting...

It's a village in the Netherlands called Bourtange (population: 430) built in and around an 18th century star fort.

How and why does it exist? That's where things get interesting...

Cannons, like gunpowder, were invented in China. They soon spread to Europe and, by the 16th century, had become incredibly advanced.

Picture a typical Medieval castle, with its knights and archers; those huge walls and towers were made redundant by the power of cannon.

Picture a typical Medieval castle, with its knights and archers; those huge walls and towers were made redundant by the power of cannon.

In response the star fort was invented.

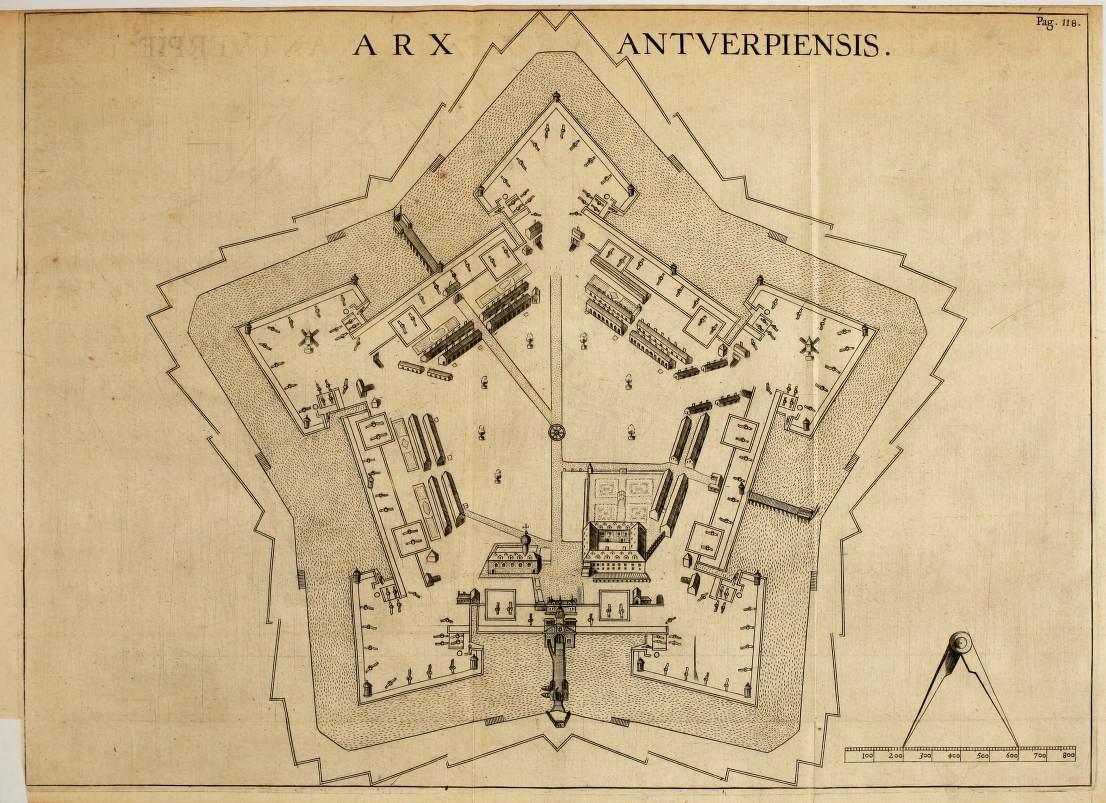

It had low, angled walls (to deflect cannon balls) and they were made from earth and faced with bricks or rubble (so that, unlike masonry, they wouldn't shatter when hit by cannon fire).

It had low, angled walls (to deflect cannon balls) and they were made from earth and faced with bricks or rubble (so that, unlike masonry, they wouldn't shatter when hit by cannon fire).

The rather strange overall layout was to ensure that enemies would always be in the line of fire, even when right up against the walls.

These increasingly complex systems of ramparts, ravelins, and bastions, surrounded by ditches, were designed to be impregnable.

These increasingly complex systems of ramparts, ravelins, and bastions, surrounded by ditches, were designed to be impregnable.

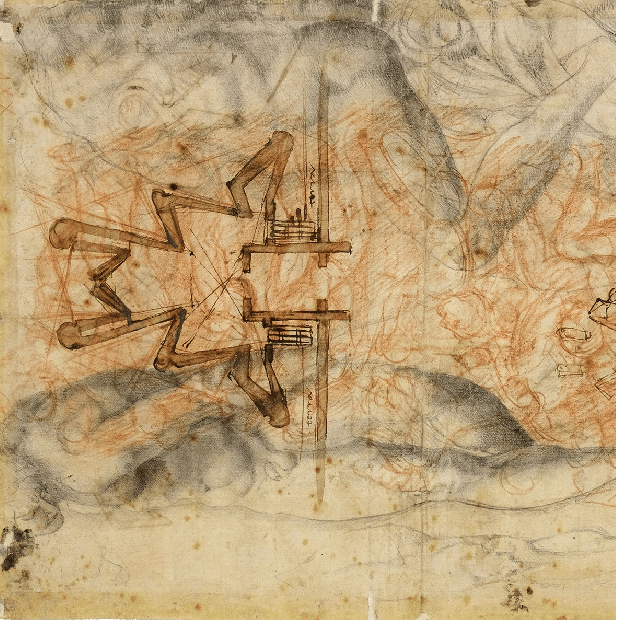

It was none other than Michelangelo himself who helped to develop some of the earliest ideas about star forts, while he was employed to design the city defences of Florence.

Later Italian architects further refined his ideas, and soon the star fort spread around Europe.

Later Italian architects further refined his ideas, and soon the star fort spread around Europe.

For three hundred years, then, the star fort was the definitive military fortification.

It was in the 1580s that William I, leader of the revolt in the Netherlands against Spain, had Fort Bourtange built in the province of Groningen, during the Eighty Years' War.

It was in the 1580s that William I, leader of the revolt in the Netherlands against Spain, had Fort Bourtange built in the province of Groningen, during the Eighty Years' War.

But the star fort was itself made redundant in the 19th century after the invention of high explosives.

And so most of these old star forts were abandoned, demolished, or decommissioned.

Though some of them have had an afterlife...

And so most of these old star forts were abandoned, demolished, or decommissioned.

Though some of them have had an afterlife...

Like Palmanova, built by the Republic of Venice in the 16th century not only as a fortified town but as an "ideal city".

This represented a major element in Renaissance thinking and its fascination with the idea of utopia.

This represented a major element in Renaissance thinking and its fascination with the idea of utopia.

Something about the star fort, with its symmetry and radiating lines, perfectly ordered and laid out, captured the imaginations of architects.

They were defensive fortifications first of all, but star forts inculcated the development of important ideas about urban planning.

They were defensive fortifications first of all, but star forts inculcated the development of important ideas about urban planning.

Then there's Neuf-Brisach, built in the late 17th century on the French border in Alsace.

It was designed by the Marquis de Vauban, perhaps the greatest military engineer of his age, whose principles and models were immensely influential.

It was designed by the Marquis de Vauban, perhaps the greatest military engineer of his age, whose principles and models were immensely influential.

And Willemstad, another Dutch fortress-village, this time incorporating a harbour — it was built along the banks of the Hollands Diep.

And, of course, like Fort Bourtange, which was decommissioned in 1851 and thereafter became a lively agricultural town.

The walls crumbled and the ditches were filled in, but the village retained the unusual layout of the fortress it had once been.

The walls crumbled and the ditches were filled in, but the village retained the unusual layout of the fortress it had once been.

But the story of Bourtange is more complicated than that.

By the mid 20th century the village had entered a state of seemingly unarrestable decline. It was falling to pieces and people were leaving; Bourtange was dying.

Until the local council came up with a brilliant idea...

By the mid 20th century the village had entered a state of seemingly unarrestable decline. It was falling to pieces and people were leaving; Bourtange was dying.

Until the local council came up with a brilliant idea...

Using surviving plans, drawings, and maps, the fort was carefully restored to the state it had been in during the 18th century, when it was at its largest and most significant.

Moats were redug, the windmill was brought back, and Fort Bourtange suddenly reemerged.

Moats were redug, the windmill was brought back, and Fort Bourtange suddenly reemerged.

The purpose was twofold.

First, to reinvigorate the village and turn it into place that was actually liveable — and where people would want to live.

Second, to create a tourist attraction and restore some of the region's cultural heritage.

By the early 1990s it was complete.

First, to reinvigorate the village and turn it into place that was actually liveable — and where people would want to live.

Second, to create a tourist attraction and restore some of the region's cultural heritage.

By the early 1990s it was complete.

And so Bourtange lives on, part open-air museum and part-village, with a small but thriving community and a healthy turnover of tourists and travellers.

Bourtange is a wonderful model for how to adapt the leftover architecture and infrastructure of the past.

What do we do with all these buildings, whether military fortifications or industrial megastructures?

Demolish them? Let them rot? Put up plaques?

What do we do with all these buildings, whether military fortifications or industrial megastructures?

Demolish them? Let them rot? Put up plaques?

Or do we transform them into living architecture?

Like the decommissioned Battersea Power Station in London, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, which has recently been turned into a mix of shops, offices, and apartments.

Like the decommissioned Battersea Power Station in London, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, which has recently been turned into a mix of shops, offices, and apartments.

There is undoubtedly something noble about ruins.

Mysterious, evocative, transporting... they retell the old and wise adage that "all things must pass" more profoundly than any book or person ever could.

Everything, no matter how powerful it seems, will fade away in time.

Mysterious, evocative, transporting... they retell the old and wise adage that "all things must pass" more profoundly than any book or person ever could.

Everything, no matter how powerful it seems, will fade away in time.

And to restore an old building can sometimes be a rather sad process.

Done poorly, the notion of "refurbishment" or "restoration" is mockery, and many buildings or structures would perhaps be better left to crumble away with dignity, sharing their wisdom with all who pass by...

Done poorly, the notion of "refurbishment" or "restoration" is mockery, and many buildings or structures would perhaps be better left to crumble away with dignity, sharing their wisdom with all who pass by...

But, sometimes, bringing back to life what might otherwise perish is surely the right approach.

That might mean restoring an old building to its former purpose and appearance, as with the derelict neo-Gothic hotel at St Pancras Station in London.

That might mean restoring an old building to its former purpose and appearance, as with the derelict neo-Gothic hotel at St Pancras Station in London.

Though when that old purpose is redundant (as with star forts) the opportunities for unusual, characterful, and interesting urban design are endless.

Like when the Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill converted a disused cement factory into his firm's offices (and his home).

Like when the Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill converted a disused cement factory into his firm's offices (and his home).

There have been many urban or rural regeneration projects, but Bourtange is surely one of the most fascinating.

All it takes is a little bit of imagination...

All it takes is a little bit of imagination...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh