🧵 Don’t say b**r

Beowulf’s name translates to “bee-wolf”. The name is an artistic euphemism, meaning bear.

Many heroes in Norse sagas are given similar kennings which indirectly mean bear. But why?

Beetlejuice.

Beowulf’s name translates to “bee-wolf”. The name is an artistic euphemism, meaning bear.

Many heroes in Norse sagas are given similar kennings which indirectly mean bear. But why?

Beetlejuice.

The Indo-European word for bear was *h₂ŕ̥tḱos. In Greek this became “arktos”; In Latin, “ursus”.

Our word “arctic” is derived from the Greek “arktos”, implying lands suitable only to the bears. A land for beasts, not man.

Our word “arctic” is derived from the Greek “arktos”, implying lands suitable only to the bears. A land for beasts, not man.

Most European languages have a word relating to the Latin “ursus”. Italian, “orso”. Spanish, “oso”, etc.

Curiously, the Northern Germanic languages developed starkly different words: German bär, Norse bjørn, and English bear.

Curiously, the Northern Germanic languages developed starkly different words: German bär, Norse bjørn, and English bear.

The English word means something like “brown one”.

The people of Northern Europe created crafty euphemisms to avoid calling bears by their actual (more ancient) name. These cultures held a belief that bears understood their real name, and would be summoned by it.

The people of Northern Europe created crafty euphemisms to avoid calling bears by their actual (more ancient) name. These cultures held a belief that bears understood their real name, and would be summoned by it.

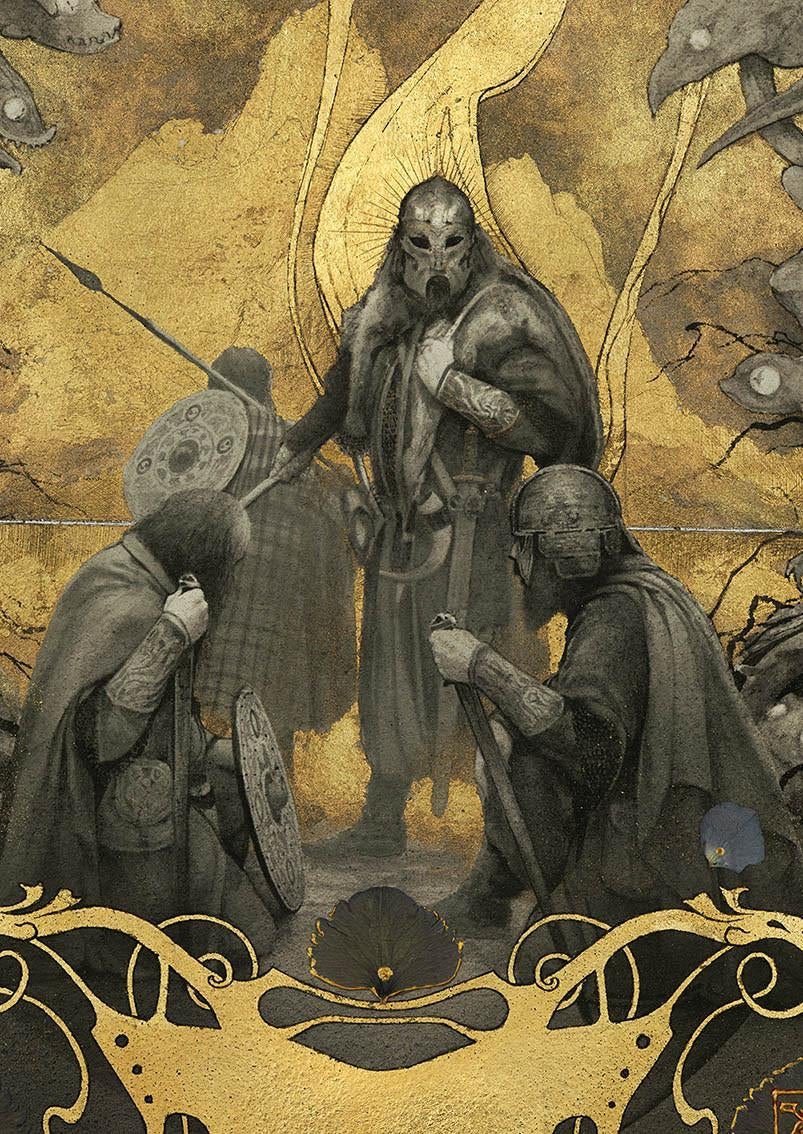

While the Norse and Germanics clearly feared these furry terrors, they also admired them. Bears embodied strength, courage, valor, and wisdom.

Naturally, they wanted their sons to possess the qualities they saw in these awesome stewards of the North.

Naturally, they wanted their sons to possess the qualities they saw in these awesome stewards of the North.

They crafted clever kennings to endow their sons with the attributes of bears, while still paying them their due respect and caution.

For example, in Hrolf Kraki’s Saga there is an entire family of “Bear people”:

For example, in Hrolf Kraki’s Saga there is an entire family of “Bear people”:

A Prince named Bjørn (meaning Bear) loves a woman named Bera (she-bear) who bears a son named Bothvar (little bear).

Bjørn is cursed to become a bear daily, while Bothvar goes on to become a renowned hero.

Bjørn is cursed to become a bear daily, while Bothvar goes on to become a renowned hero.

In fact, like Beowulf, Bjørn saves a Danish hall from a monster (in this case essentially a dragon) which brought destruction every Yule.

Such motifs where a warrior associated with a bear performs tremendous feats of heroism became a common archetype.

Such motifs where a warrior associated with a bear performs tremendous feats of heroism became a common archetype.

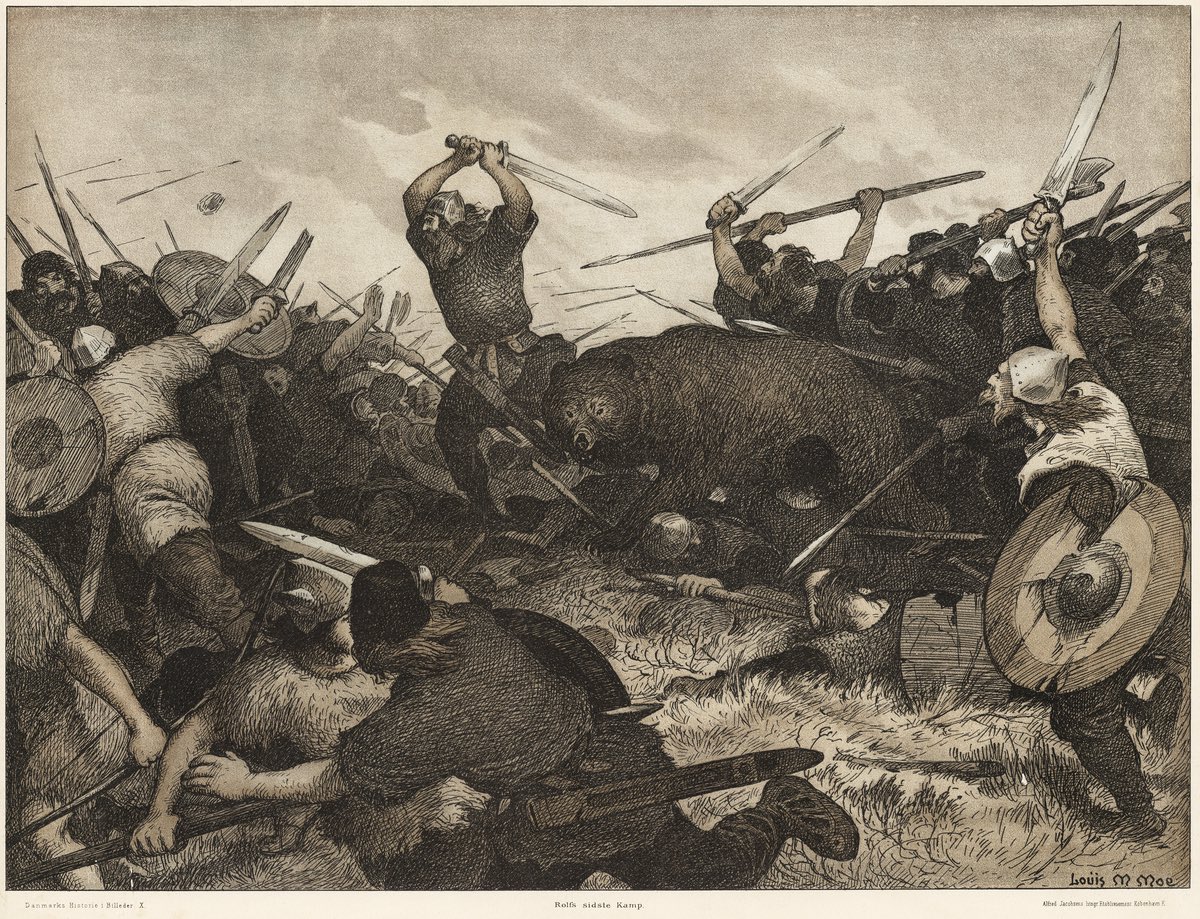

Of course some Norse were also known to be Berserkers, men who channeled the spirit of the bear into their fighting, often wearing bear or wolf pelts into battle. In the sagas these men are often portrayed as abandoning all reason for animalistic rage.

Other warriors in Norse literature partially take on berserker-like qualities, without becoming one themselves.

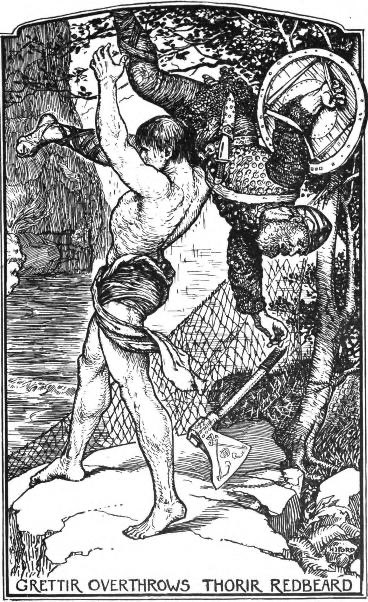

For example in Grettir’s Saga a man named Bjørn insults our hero by throwing his cloak into a bear’s den.

For example in Grettir’s Saga a man named Bjørn insults our hero by throwing his cloak into a bear’s den.

Grettir defeats the bear, foreshadowing his triumph of Bjørn. He brings back the paw of the bear, a trophy similar to one typically taken by a Berserker.

Yet Grettir is no Berserk, and he frequently kills the loathsome and criminal berserkers he encounters.

Yet Grettir is no Berserk, and he frequently kills the loathsome and criminal berserkers he encounters.

Grettir then shows a bear warrior aligned with Beowulf and Bothvar. They are men endowed with traits of bears but retaining the wit and virtue of men. Unlike a berserker, they are not prone to mindless frenzy but display the cunning and strength of the “brown one”.

It’s not hard to squint at this and see the beginnings of chivalry emerging from these northern cultures. Beowulf represents one evolution between traditional Norse heroes and later Arthurian Legends with the baptism of the bear man.

*correction: it is Bothvar that saves the Danish hall.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter