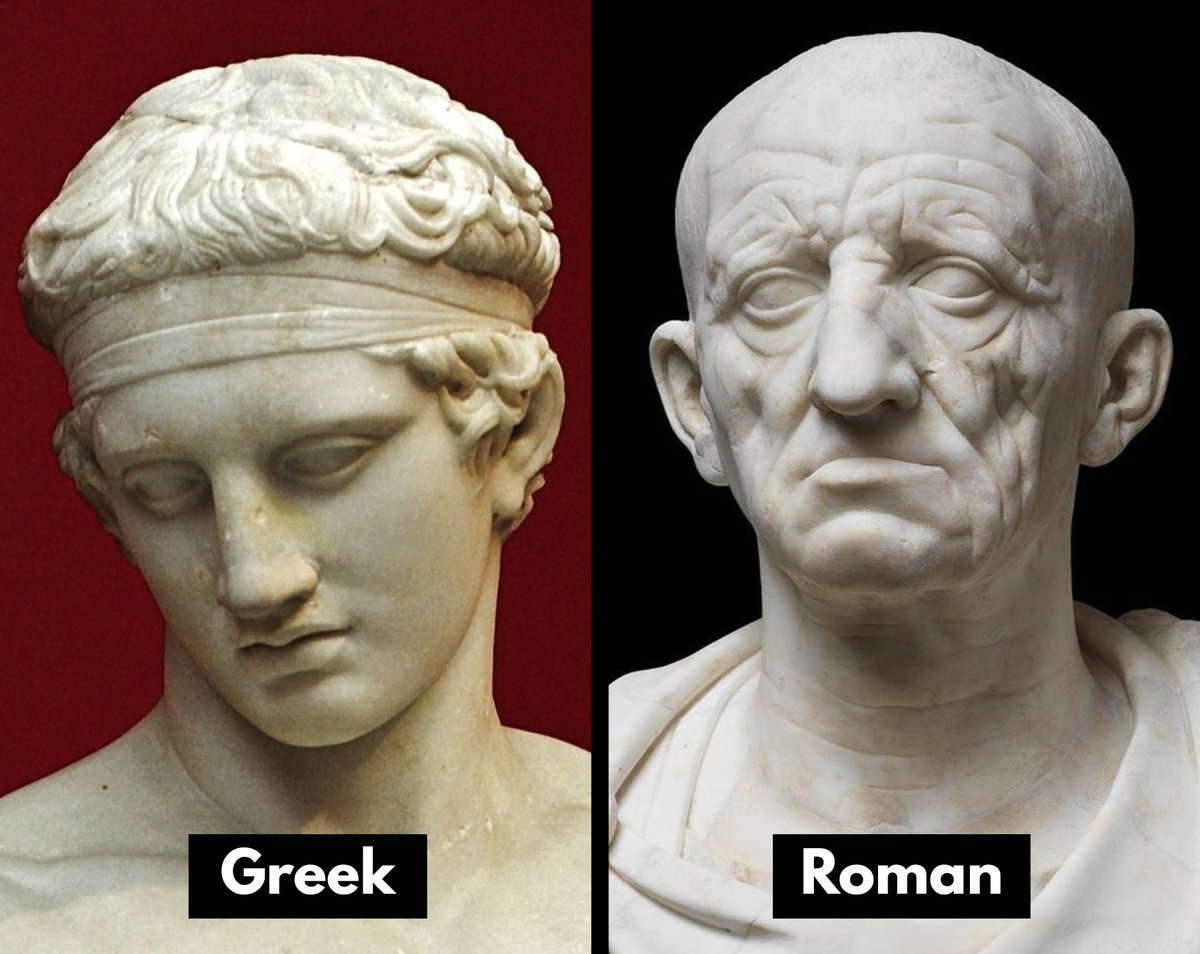

Want to know the difference between the Ancient Greeks and the Ancient Romans? Just look at their statues.

Art always tells you what a society wants to believe about itself.

So, from the Soviet Union to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, here's what art says about who we are...

Art always tells you what a society wants to believe about itself.

So, from the Soviet Union to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, here's what art says about who we are...

We begin in Ancient Greece, with an Athenian statue from the 5th century BC.

Here is the victor of an athletic contest. What do we see?

This is not a specific individual; it is a generic, idealised face and body.

Here is the victor of an athletic contest. What do we see?

This is not a specific individual; it is a generic, idealised face and body.

The same is true for many Greek statues from the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

Their faces and bodies are not intended to be those of real people. Rather, they represent the Greek ideal of what a human being can be, and what a human ought to aspire to become.

Their faces and bodies are not intended to be those of real people. Rather, they represent the Greek ideal of what a human being can be, and what a human ought to aspire to become.

And even when a specific person is portrayed, and we can clearly see the features of a recognisable individual, they are still idealised.

Lysippos' bust of Alexander was praised for how it maintained his appearance and personality while also giving it a god-like countenance.

Lysippos' bust of Alexander was praised for how it maintained his appearance and personality while also giving it a god-like countenance.

Now, for contrast, look at statues from the Ancient Roman Republic, in this case from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.

The difference is striking. There is no idealisation here, no attempt to portray human beauty. These are the real faces of real people, warts and wrinkles and all.

The difference is striking. There is no idealisation here, no attempt to portray human beauty. These are the real faces of real people, warts and wrinkles and all.

And this makes sense. For the Ancient Romans poverty was a virtue. They thought of themselves as hard-headed, honest, vigorous people.

To have a weatherbeaten face, worn with age and work, was a sign of wisdom and of virtue.

The ideal Roman was simple, not beautiful.

To have a weatherbeaten face, worn with age and work, was a sign of wisdom and of virtue.

The ideal Roman was simple, not beautiful.

And so the Romans were uneasy about the Greeks.

When Ancient Greek art first arrived in Rome, along with Greek philosophy, many people called it decadent, luxurious, and corrupting.

But, in the end, Greek culture won and the Romans were thoroughly Hellenised.

When Ancient Greek art first arrived in Rome, along with Greek philosophy, many people called it decadent, luxurious, and corrupting.

But, in the end, Greek culture won and the Romans were thoroughly Hellenised.

It may be true that the Romans weren't *actually* the sort of honest, down-to-earth people they wanted to seem like in their art.

But this makes it more interesting: these statues reflect what they *wanted* to be, even more than what they really were.

But this makes it more interesting: these statues reflect what they *wanted* to be, even more than what they really were.

And this doesn't stop with the Greeks and the Romans.

It has always been true that we can trust a society's art more than what they said about themselves to figure out who they were and what was important to them.

First and foremost through *what* it depicts...

It has always been true that we can trust a society's art more than what they said about themselves to figure out who they were and what was important to them.

First and foremost through *what* it depicts...

The art of Ancient Mesopotamia was filled with bulls and sheep; we may conclude that this was an agricultural society.

In Ancient Egypt, meanwhile, we find monumental statues of Pharaohs; it seems clear that these were figures who possessed almost unimaginable power.

In Ancient Egypt, meanwhile, we find monumental statues of Pharaohs; it seems clear that these were figures who possessed almost unimaginable power.

In the lead up to the French Revolution there was a major shift in French art.

Throughout the 18th century it was rather frivolous, hedonistic depictions of the aristocracy that had dominated art, as in the work of Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

Throughout the 18th century it was rather frivolous, hedonistic depictions of the aristocracy that had dominated art, as in the work of Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

But soon it was scenes from Ancient Roman history that became popular, as in the work of Jacques-Louis David.

Notice too the stylistic shift: from bright colours and loose brushwork to harsh lines and more severity.

Times were clearly changing — revolution followed.

Notice too the stylistic shift: from bright colours and loose brushwork to harsh lines and more severity.

Times were clearly changing — revolution followed.

It's no coincidence that Horatio Greenough's statue of George Washington, made in 1832, portrays America's first President as a Classical hero.

The Founding Fathers saw themselves as the inheritors of Greece and Rome.

Art, once again, expressing self-perception.

The Founding Fathers saw themselves as the inheritors of Greece and Rome.

Art, once again, expressing self-perception.

In the 19th century it was normal to make statues of politicians and generals — consider Nelson's Column in London, built in honour of Admiral Nelson.

This might either tell us politicians and generals were held in higher regard back then, or simply indicate who held most power.

This might either tell us politicians and generals were held in higher regard back then, or simply indicate who held most power.

In the 21st century? Statues of sporting stars are far more common than statues of politicians or generals.

Perhaps it indicates how much more democratic we have become, when the real heroes of the people — rather than those who simply hold power — are revered the most.

Perhaps it indicates how much more democratic we have become, when the real heroes of the people — rather than those who simply hold power — are revered the most.

What did Soviet art depict? One of two things: either the political leaders, as in this colossal and now-demolished statue of Stalin.

Or the workers, as in the huge Worker and Kolkhoz Woman statue.

Art and artists in service of the state.

Or the workers, as in the huge Worker and Kolkhoz Woman statue.

Art and artists in service of the state.

The portrayal of working people in art was nothing new — the difference came in *how* they were depicted.

Jean-François Millet's The Gleaners, an early example of Realism, portrays workers in a wholly unidealised way.

As opposed to Soviet art, in which workers were heroised.

Jean-François Millet's The Gleaners, an early example of Realism, portrays workers in a wholly unidealised way.

As opposed to Soviet art, in which workers were heroised.

Throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance there were endless paintings of Mary and Jesus.

That these were deeply religious societies is clear, but look at how much these paintings differ stylistically.

Art also tells us how a society sees and understands the world.

That these were deeply religious societies is clear, but look at how much these paintings differ stylistically.

Art also tells us how a society sees and understands the world.

Medieval art was much less "realistic", but this changed during the Renaissance.

One style represents a more distant and symbolic understanding of the world, while the other suggests a proto-scientific one, in which the world exists to be investigated and understood.

One style represents a more distant and symbolic understanding of the world, while the other suggests a proto-scientific one, in which the world exists to be investigated and understood.

Much Western art of the 20th century, from Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism, seems to indicate an uncertainty about the world, about reality, and even about humankind.

Strange, incomprehensible, discomforting.

An accurate reflection of how many feel about modern life?

Strange, incomprehensible, discomforting.

An accurate reflection of how many feel about modern life?

Of course, the most popular art forms of the 21st century are cinema and television, and most popular of all are superheroes.

Is it a form of honest escapism? Or do we want to believe that, like our superheroes, we are in some way special and different from everybody else?

Is it a form of honest escapism? Or do we want to believe that, like our superheroes, we are in some way special and different from everybody else?

And so art also expresses social anxieties.

19th century Romanticism was a reaction against the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

The Romantics preferred mystery, emotion, and nature to science, reason, and industry — they feared the effects of the latter.

19th century Romanticism was a reaction against the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

The Romantics preferred mystery, emotion, and nature to science, reason, and industry — they feared the effects of the latter.

Whether a renewed focus on the beauty of the natural world itself or a fascination with its cataclysmic power — which we, however clever we think ourselves, are helpless to resist — the message is clear.

Horror at the ongoing destruction of nature, literally and spiritually.

Horror at the ongoing destruction of nature, literally and spiritually.

Actions speak louder than words, because actions result from choices, and choices are a consequence of priorities and intentions.

Art — making it and consuming it — is action. And so through art we can read into those choices, priorities, and intentions.

Art — making it and consuming it — is action. And so through art we can read into those choices, priorities, and intentions.

What a society believes in, how it sees itself, what it wants to be — art tells us all of this.

What a society feared, how it worked, who held power — art also tells us this.

And so, if we want to understand the 21st century, art might be the best way to do so...

What a society feared, how it worked, who held power — art also tells us this.

And so, if we want to understand the 21st century, art might be the best way to do so...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh