The Blue Banana—an arc through Western Europe containing an exceptionally high % of GDP and population—is one of those fashionable concepts like BRICS that looks nice at first glance, but doesn’t necessarily reveal anything deeper.

But supposing it does, what is it? Thread.

But supposing it does, what is it? Thread.

There are four big factors:

-Physical geography

-Trade patterns encouraging industrial development

-Resource geography

-Historic political fragmentation

These help explain not only why the Blue Banana is so densely developed, but why other advanced regions aren’t.

-Physical geography

-Trade patterns encouraging industrial development

-Resource geography

-Historic political fragmentation

These help explain not only why the Blue Banana is so densely developed, but why other advanced regions aren’t.

1. Physical Geography

Looking at a population map, the Blue Banana is actually three disconnected parts: England, the greater Rhineland, and Lombardy. https://t.co/rra25u9iZftwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Looking at a population map, the Blue Banana is actually three disconnected parts: England, the greater Rhineland, and Lombardy. https://t.co/rra25u9iZftwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Each of these is internally densely connected. England because of the high number of coastal ports plus the Thames and Severn waterways.

The greater Rhineland, with all its subsidiary and parallel waterways, connected an enormous area that could also feed a large population.

Each of these regions was also physically connected to the others. There were land links between the Rhineland and Italy all through the Middle Ages, and in the later centuries by sea. There was always sea traffic between England and the Continent.

https://t.co/ar5KbgpJMn

https://t.co/ar5KbgpJMn

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1529471688567578625

When transoceanic trade took off in the 16thcentury, this put England and the Netherlands at an especial advantage: they had direct access to the Atlantic and to existing commercial regions. ![Source: https://jcheshire.com/featured-maps/mapped-british-shipping-1750-1800/]](/images/1px.png)

![Source: https://jcheshire.com/featured-maps/mapped-british-shipping-1750-1800/]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/F11eFnGWAAEx4rG.jpg)

Compare this to the centers of oceanic trade in France, Spain, or Portugal.

Iberia has virtually no inland waterways—only the Guadalquivir is navigable very far upstream.

Iberia has virtually no inland waterways—only the Guadalquivir is navigable very far upstream.

France’s Atlantic coast did connect to the waterways of the northeast via canals from the Loire to the Saône and Seine, but that required passing through extensive lock systems—easier to just take the coastal route to Amsterdam, Marseilles, or wherever.

The real outlier is eastern France, which has two great river systems and neighbors a third, but never got integrated into the Rhineland. More on that in a bit.

2. Historic exchanges that encourage industry

Geography is necessary for trade, but still requires an economic incentive. The trade fairs of northern Europe spurred development of the Italian cloth industry, and later encouraged local manufacturing.

https://t.co/0co9f29I1t

twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

Geography is necessary for trade, but still requires an economic incentive. The trade fairs of northern Europe spurred development of the Italian cloth industry, and later encouraged local manufacturing.

https://t.co/0co9f29I1t

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1682838754409455617

twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

English wool was eagerly consumed by Flemish clothmakers. This trade was so profitable that English kings eventually started encouraging domestic production.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1682127296650518531

Meanwhile, Venice’s trade with the East galvanized its own industries:

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1683204589590380546

3. Resource geography

As already mentioned, England was an excellent producer of wool, while the greater Rhineland & Lombardy were both fertile areas that supported large populations (sidenote: it’s funny to think about terms like HR, it’s basically calling people "resources"). https://t.co/HY4CcGpzXktwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

As already mentioned, England was an excellent producer of wool, while the greater Rhineland & Lombardy were both fertile areas that supported large populations (sidenote: it’s funny to think about terms like HR, it’s basically calling people "resources"). https://t.co/HY4CcGpzXktwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

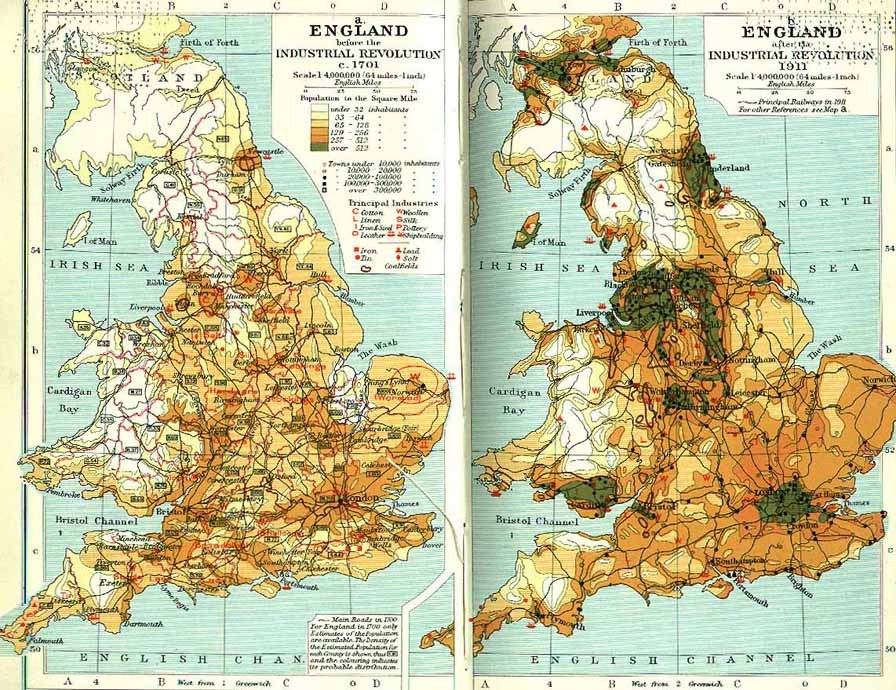

But what most shaped the present were the resources of the industrial age: coal and iron.

Industry developed basically wherever there was coal, and a high proportion of that was within the Blue Banana (apologies for the poor image quality).

Industry developed basically wherever there was coal, and a high proportion of that was within the Blue Banana (apologies for the poor image quality).

4. Political fragmentation

This is the most interesting factor. Geography, natural resources, and economic incentives are all impersonal forces, but politics involve human decisions. And often successful statecraft led to worse development. https://t.co/HvhoMrO7Ubtwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

This is the most interesting factor. Geography, natural resources, and economic incentives are all impersonal forces, but politics involve human decisions. And often successful statecraft led to worse development. https://t.co/HvhoMrO7Ubtwitter.com/i/web/status/1…

There are two parts to this.

The first is that, while states of all sizes have reason to centralize, it only causes major disruption in big states. England was always politically centralized, but also relatively small, its population concentrated in the south and coasts.

The first is that, while states of all sizes have reason to centralize, it only causes major disruption in big states. England was always politically centralized, but also relatively small, its population concentrated in the south and coasts.

This is much different for a larger kingdom like France, which began to centralize in the 12th century. This drew a lot of economic activity to Paris, encouraged by policy and infrastructure investment.

You can see it in this map of postal routes in the 17th century…

You can see it in this map of postal routes in the 17th century…

…and especially in this comparative chart of city populations. Paris is consistently WAY bigger than all other French cities, whereas there is a much more even distribution among the Italian and German/Low Countries cities.

The other part is that big states are less reliant on trade revenues.

The fate of the Champagne fairs are a prime example.

The Counts initially used the fairs to draw Italian commerce to their lands. But in the late 13th century, Champagne was absorbed by the French crown.

The fate of the Champagne fairs are a prime example.

The Counts initially used the fairs to draw Italian commerce to their lands. But in the late 13th century, Champagne was absorbed by the French crown.

French kings drew their most of their wealth from agriculture, so they didn’t have to play nice with commercial interests. Philip the Fair expropriated various bankers over the course of his reign—Lombard, Jews, and Templars—which had a ruinous effect on trade.

Similarly, the Spanish Crown defaulted numerous times in the 16th & 17th centuries (under another series of Philips—there is a pattern), which had an effect on state-backed commerce.

In a more indirect way, there's another reason that political centralization might have contributed to the relative underdevelopment of promising regions like eastern France: the long rivalry between the Habsburgs and the French.

https://t.co/pyUvji3NZ8

https://t.co/pyUvji3NZ8

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1683605774784667649

The Habsburgs emerged victorious from the Italian Wars by the mid-16th century, leaving them in possession of most of the Blue Banana. The conflict between them carried on for another two centuries, creating a line that cut right through eastern France.

A map of the Spanish Road, used by Spanish troops to suppress the Dutch Revolt in the 16th & 17th centuries, shows this clearly. Habsburg possessions divided the Rhone-Saône system from both the river systems of northern France and the upper Rhine.

This even though the Rhone valley was a promising center of development, providing access deep into the interior from the Mediterranean, with towns like Lyon that were already centers of commerce and industry.

Meanwhile, the Low Countries and northern France were a military frontier from the late Middle Ages to the Napoleonic Wars, cutting the Seine, Meuse, etc. off from the lower Rhine.

https://t.co/ut13B7mJzc

https://t.co/ut13B7mJzc

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1682127743452954624

It is hard to say have much of an effect this had—commerce often thrives across battlelines, but centuries of sustained warfare are bound to leave their mark.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1500504467862691845

Putting all this together, the, there is indeed something that connects the Blue Banana at a profound level, spanning the longue durée of the last millennium.

But at the same time, there was nothing inevitable about it.

But at the same time, there was nothing inevitable about it.

As the last point suggests, the outcome ultimately depended on a myriad of individual human actions: generals, inventors, sailors, craftsmen, merchants, statesmen, builders, lawyers, and more.

History may tilt in a certain direction, but it is never preordained.

History may tilt in a certain direction, but it is never preordained.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter