Superconducting magnet engineer chiming in.

This result could be very big news, and overnight revolutionize all of electronics and energy. It might not.

Here's a mental model for the non-expert to understand what's going on.

RTAPS: The good, the bad, and the ugly: 🧵

This result could be very big news, and overnight revolutionize all of electronics and energy. It might not.

Here's a mental model for the non-expert to understand what's going on.

RTAPS: The good, the bad, and the ugly: 🧵

Summary

The good: There's some plausibility here, and if so, it's game-changing

The bad: Reasonable chance this is a similar but different physical property

The ugly: Their plots, and engineering usefulness

Let me explain:

The good: There's some plausibility here, and if so, it's game-changing

The bad: Reasonable chance this is a similar but different physical property

The ugly: Their plots, and engineering usefulness

Let me explain:

The Good:

Lee-Kim-Kwon (LKK) use familiar materials, Cuprates, and measures some key metrics of a room-temp superconductivity (SC):

- Zero-resistivity

- Critical current

- Critical magnetic field

- Meissner effect

Lee-Kim-Kwon (LKK) use familiar materials, Cuprates, and measures some key metrics of a room-temp superconductivity (SC):

- Zero-resistivity

- Critical current

- Critical magnetic field

- Meissner effect

For context, past progress was measured by successively higher temperatures using new kinds of materials. LKK result does fit the rough trend of increasing temperatures, but, they do it at ambient pressure.

The highest-temperature results before were at >1 million atmospheres

The highest-temperature results before were at >1 million atmospheres

To understand, think of electrons normally bouncing off everything as they fall, plinko-style; in SC they glide smoothly. To make electrons glide, either you cool them down a lot, or squeeze them together.

Therefore you can sort of just trade pressure for temperature

Therefore you can sort of just trade pressure for temperature

The key difference in LKK paper is this: the channel for letting electrons glide doesn't come from low temp, or by squeezing together.

It comes from an internal tension that forms as the material forms, just like the tempered glass of a car windshield.

It comes from an internal tension that forms as the material forms, just like the tempered glass of a car windshield.

LKK hypothesis that copper atoms are percolating into the crystal and replacing lead atoms, and this creates a structural shrinkage of ~0.5% and produces internal strains, creating this smooth-electron-channel

Good: Plausible materials, fits an overall trend, easy to reproduce

Good: Plausible materials, fits an overall trend, easy to reproduce

The bad:

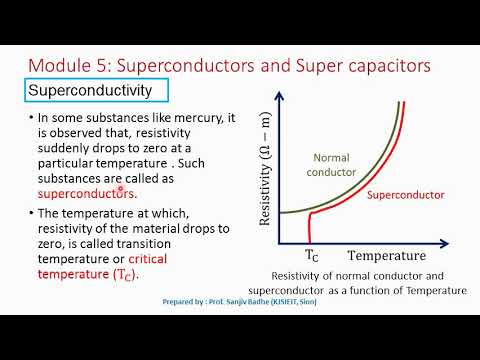

Normally the superconducting transition temperature is predicted by measuring heat capacity versus temperature. This is the Debye Temp.

TKK say they can't measure this, because the usual theories of SC don't explain their sample: a lil bit sus

Normally the superconducting transition temperature is predicted by measuring heat capacity versus temperature. This is the Debye Temp.

TKK say they can't measure this, because the usual theories of SC don't explain their sample: a lil bit sus

There's two two papers published, which present results in different ways, using different scalings. One result seems almost unphysical altogether.

Normally SC's perfectly repel magnetic field, or have a diamagnetism of -1. These guys report it as -154

Normally SC's perfectly repel magnetic field, or have a diamagnetism of -1. These guys report it as -154

A 'super diamagnetic' could also weakly levitate itself above a large permanent magnet, like what the authors video shows.

There's some reason for caution here, but this could also boil down to non-standard presentation of results and genuine impurities in the sample

There's some reason for caution here, but this could also boil down to non-standard presentation of results and genuine impurities in the sample

The ugly:

Some of their plots.

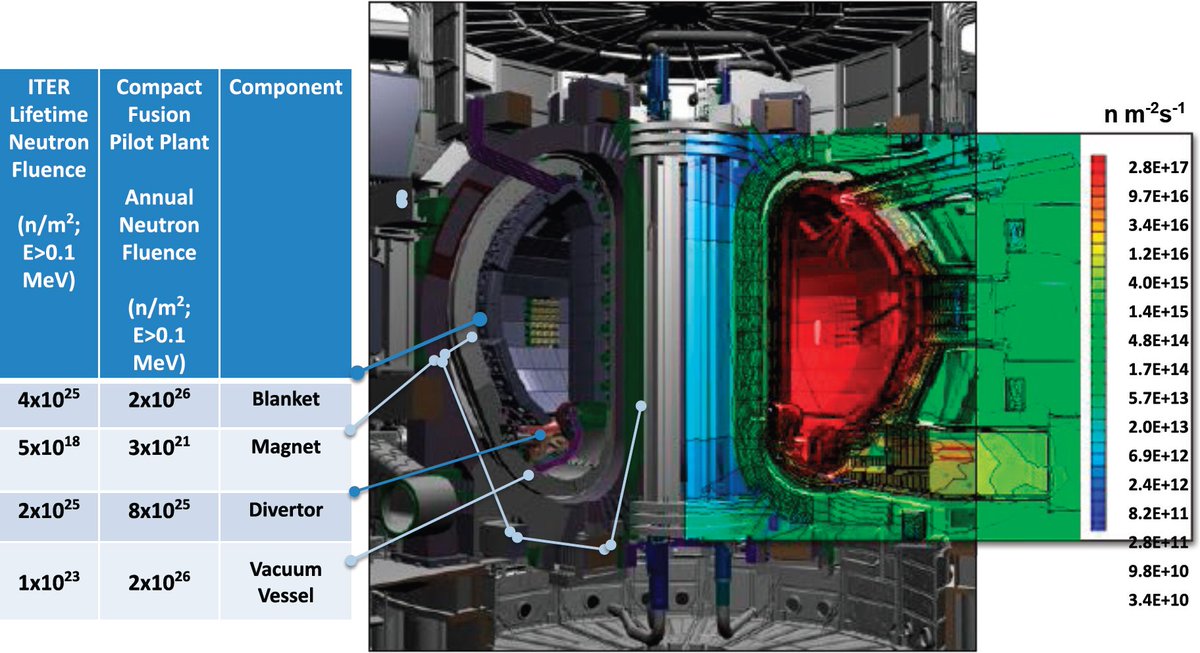

More seriously, there's really three numbers that are relevant for superconductors in engineering practice:

Current density, magnetic field, and temperature.

Some of their plots.

More seriously, there's really three numbers that are relevant for superconductors in engineering practice:

Current density, magnetic field, and temperature.

You can think of it as your 'magnet budget' that you get to spend on either high current density, high magnetic fields, or high temperature. There are limits too - you need to stay well below Tc, and, pushing the limits will burn out your magnets by 'quenching' them

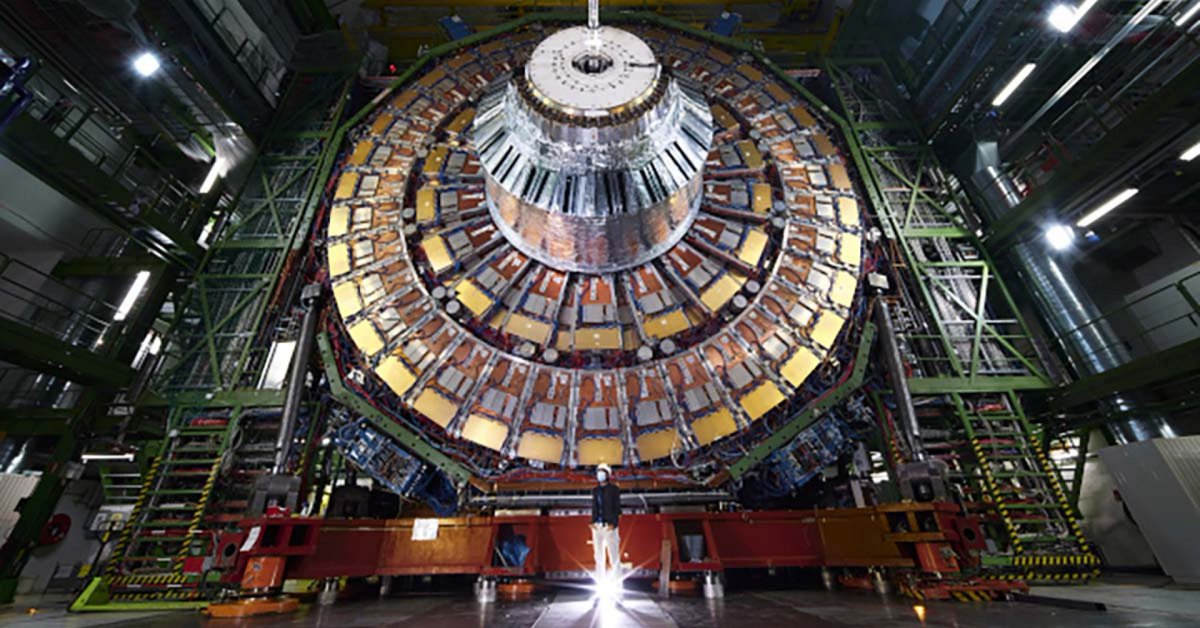

If you want to design a magnetic confinement fusion reactor, you need a balance of all three: magnets that can withstand their own high field, be compact, and not require too much cooling

LKK haven't put out a full set of numbers on critical current density, just total current, so its hard to compare. However, magnets for fusion have to withstand fields of ~10 Tesla or more, or about 300x the fields that kill off SC in their samples

That being said, the temperatures these operate at are enormous by comparison. In Fusion, the magnet-killer is the neutron heat flux that escapes through the reactor walls and heats up your coils.

Heat-resistant coils would still make my job 10x easier

Heat-resistant coils would still make my job 10x easier

The net-net:

No champagne yet, but watch closely - this would be a serious game changer in things like power transmission, energy storage, and future-tech like quantum computers, fusion energy, mag-lev trains.

I'm even more optimistic than 6 weeks ago

No champagne yet, but watch closely - this would be a serious game changer in things like power transmission, energy storage, and future-tech like quantum computers, fusion energy, mag-lev trains.

I'm even more optimistic than 6 weeks ago

https://twitter.com/Andercot/status/1666629851305111554?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter