Dresden, Germany — a beautiful and historic city.

Not exactly. Everything you see here has been built in the last 25 years...

Not exactly. Everything you see here has been built in the last 25 years...

In 1945 the German city of Dresden was devastated by Allied bombers.

4,000 tons of high explosives were dropped on the city; a firestorm broke out and at least 25,000 people died. This was among the worst of WWII's many tragedies.

Here's how Dresden looked before 1945:

4,000 tons of high explosives were dropped on the city; a firestorm broke out and at least 25,000 people died. This was among the worst of WWII's many tragedies.

Here's how Dresden looked before 1945:

And here is Dresden after the bombs had been dropped and the fires had died down.

More than ninety percent of the city centre had been destroyed, including the 18th century Frauenkirche, a masterpiece of Northern European Baroque architecture and an important Protestant church.

More than ninety percent of the city centre had been destroyed, including the 18th century Frauenkirche, a masterpiece of Northern European Baroque architecture and an important Protestant church.

Destroyed or ruined too were the Semper Opera House, the Catholic Cathedral, the Academy of Fine Arts, and the entirety of the old city centre, known as the Neumarkt.

What happened next? Some of the old buildings were reconstructed by the East German Government, including the Semper Opera, but otherwise much of old Dresden remained empty.

While the blackened stumps of the Frauenkirche survived as a memorial to those who had died in the war.

While the blackened stumps of the Frauenkirche survived as a memorial to those who had died in the war.

After the fall of Communism and the reunification of Germany in 1991 things started to change.

In 1994 the Stiftung Frauenkirche Dresden was founded: an organisation dedicating to rebuilding the Frauenkirche exactly as it had been before its destruction...

In 1994 the Stiftung Frauenkirche Dresden was founded: an organisation dedicating to rebuilding the Frauenkirche exactly as it had been before its destruction...

And by the year 2005 this apparently ambitious goal had been achieved.

Exactly seventy years after the bombing of Dresden the new Frauenkirche was consecrated, with remaining elements of the original 18th century church incorporated into its modern reincarnation.

Exactly seventy years after the bombing of Dresden the new Frauenkirche was consecrated, with remaining elements of the original 18th century church incorporated into its modern reincarnation.

And so the Semper Opera House, the Cathedral, the Academy of Fine Arts... all have been rebuilt or restored to their pre-war state, in consultation with historical documents and architectural experts.

Old Dresden has been meticulously and lovingly brought back to life.

Old Dresden has been meticulously and lovingly brought back to life.

In 1999 the Dresden Historical Neumarkt Society was founded, dedicated to rebuilding the Neumarkt.

Crucial here was a public survey which indicated overwhelming support for the reconstruction of the Neumarkt. Those in charge listened to the people, and the project went ahead...

Crucial here was a public survey which indicated overwhelming support for the reconstruction of the Neumarkt. Those in charge listened to the people, and the project went ahead...

The Neumarkt has re-emerged from its rubble. Nobody visiting the city now would know that just two decades ago none of these buildings existed.

Some architects protested that this was inauthentic and superficial, but local people and tourists didn't seem to mind.

Some architects protested that this was inauthentic and superficial, but local people and tourists didn't seem to mind.

What happened in Dresden is not unusual; innumerable cities all around Europe had been gutted by the war, if not quite so badly.

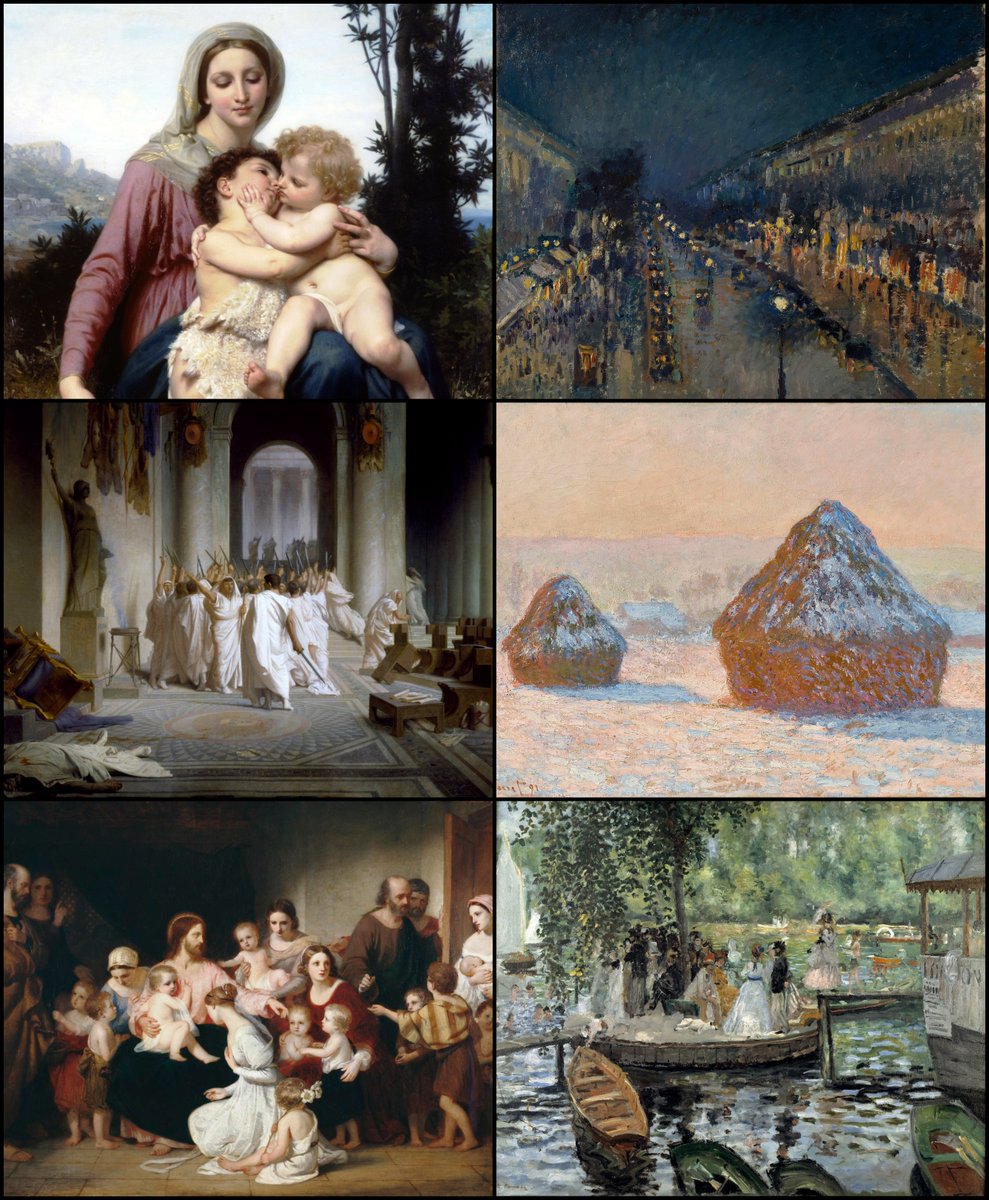

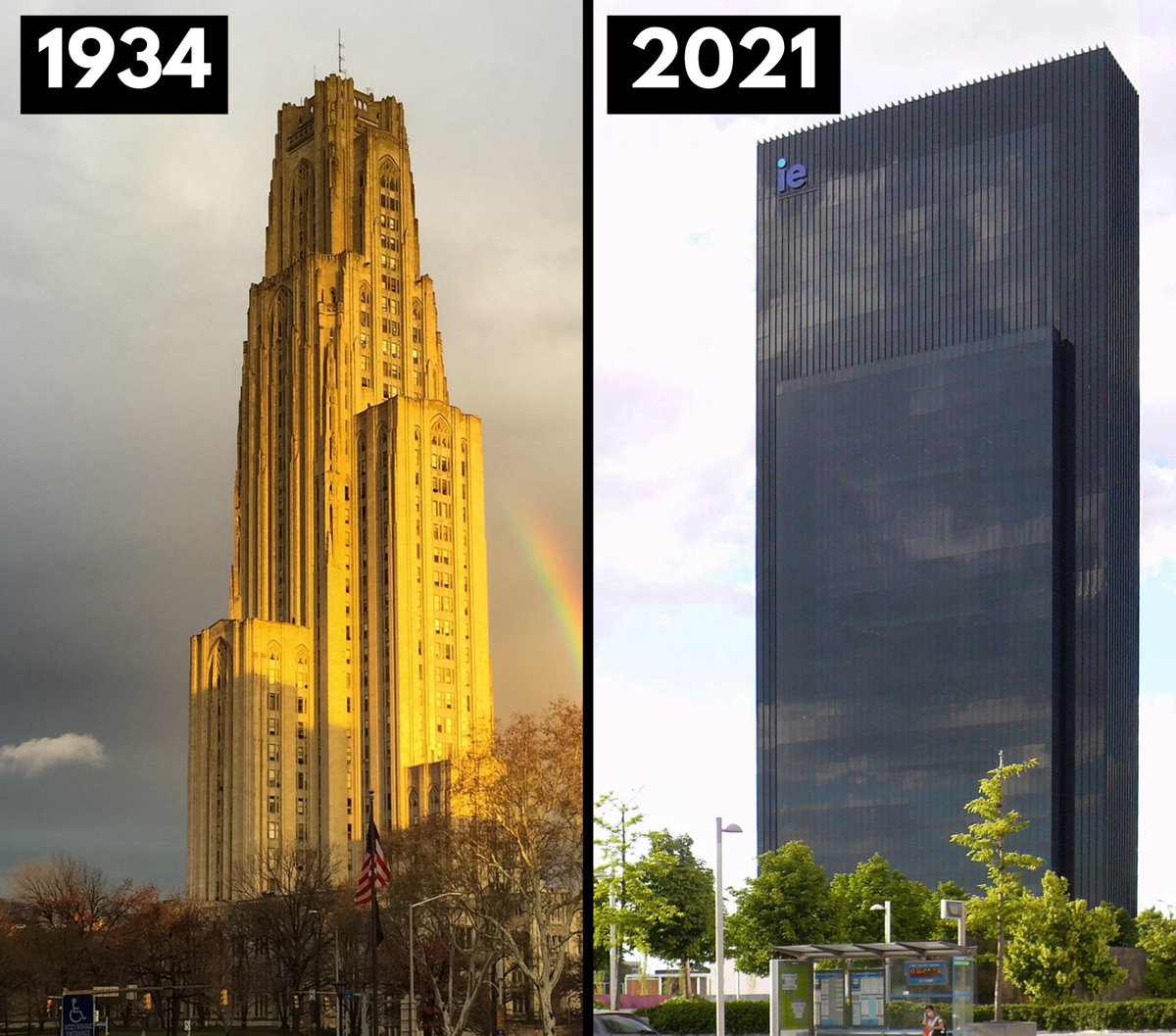

But in many places a decision was taken to build something new rather than reconstruct; Modernist architecture was given its chance to shine.

But in many places a decision was taken to build something new rather than reconstruct; Modernist architecture was given its chance to shine.

Why? Well, here was a unique chance to fix old problems of urban design by creating better housing, public services, and spaces.

In other words, the chance to build a better world.

London's celebrated Barbican Centre was built in an area destroyed during the Blitz.

In other words, the chance to build a better world.

London's celebrated Barbican Centre was built in an area destroyed during the Blitz.

But not all such postwar projects have been equally successful.

In many cases, despite the genuine optimism that accompanited their construction in the 1950s and 1960s, these quasi-utopian projects have failed to deliver on what they promised.

In many cases, despite the genuine optimism that accompanited their construction in the 1950s and 1960s, these quasi-utopian projects have failed to deliver on what they promised.

But in others, like Dresden, the public made their opinions clear and the local authorities acted accordingly.

Decades on, tourists visiting cities like Munich or Warsaw have no idea that they are walking around "historic centres" (re)built relatively recently.

Decades on, tourists visiting cities like Munich or Warsaw have no idea that they are walking around "historic centres" (re)built relatively recently.

Another example, from the First World War, is that of the Great Cloth Hall in Ypres, Belgium, a masterpiece of Medieval architecture.

It was initially going to be left as a memorial, but the plan changed and by 1967 it had been rebuilt exactly as it once stood, brick for brick.

It was initially going to be left as a memorial, but the plan changed and by 1967 it had been rebuilt exactly as it once stood, brick for brick.

Perhaps the most interesting case study of all is Frankfurt, where the old city centre was destroyed by bombs and then replaced by a complex of Modernist buildings in the decades after the war.

The public never warmed to their new town centre, and since the launch of a major project in 2012 those Modernist building have been demolished and replaced by a reconstruction of the town centre as it existed prior to the Second World War.

What do we make of all this?

Well, the claim that it is no longer possible to build in historical styles is disproven by the Frauenkirche in Dresden, the old towns of Warsaw, Frankfurt, or Munich, the Great Cloth Hall of Ypres, among so many more examples.

Well, the claim that it is no longer possible to build in historical styles is disproven by the Frauenkirche in Dresden, the old towns of Warsaw, Frankfurt, or Munich, the Great Cloth Hall of Ypres, among so many more examples.

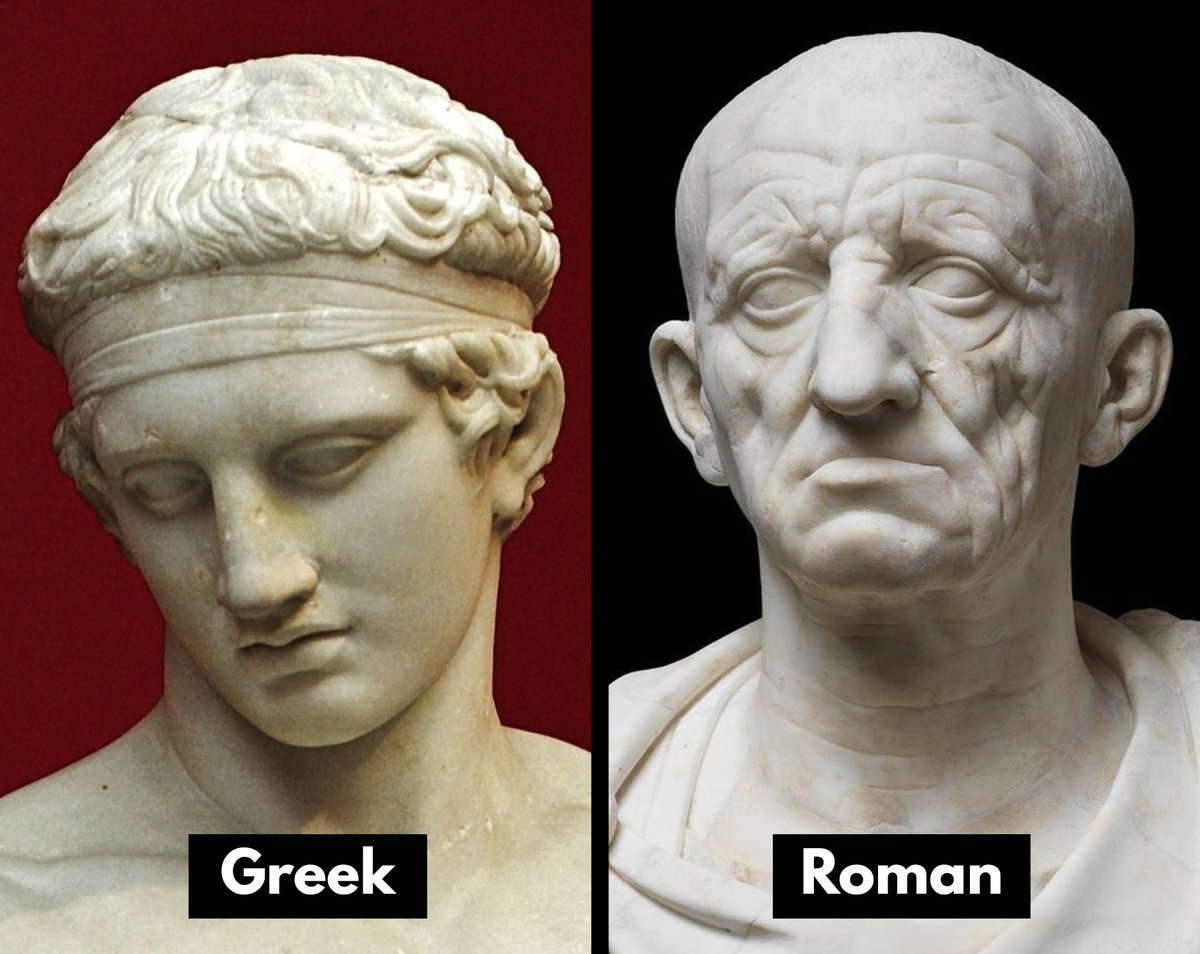

They are evidence that we would be wrong to draw a hard line between the architecture of the past and present.

To say that modern architecture (often unfairly maligned!) is a necessity does not account for these many reconstructions; they suggest that we always have a choice.

To say that modern architecture (often unfairly maligned!) is a necessity does not account for these many reconstructions; they suggest that we always have a choice.

Some say it is inauthentic to simply imitate the styles of the past, and wholly artificial to reconstruct long-destroyed old buildings using modern materials — the reconstruction of Dresden was met with these very criticisms.

Better to build something true to the 21st century...

Better to build something true to the 21st century...

Perhaps, but one can hardly call Dresden a Potemkin City.

And in two or three hundred years all this "new" architecture will be old once again; accusations of inauthenticity will cease to hold water.

Besides, most people care less about "authenticity" than aesthetics.

And in two or three hundred years all this "new" architecture will be old once again; accusations of inauthenticity will cease to hold water.

Besides, most people care less about "authenticity" than aesthetics.

And what's wrong with creating buildings the public love?

This is not to spite modern architecture — which has seen many beloved triumphs. Rather, when we know what the public want, and when we know it's possible to provide it, *not* doing so is surely worse than inauthenticity.

This is not to spite modern architecture — which has seen many beloved triumphs. Rather, when we know what the public want, and when we know it's possible to provide it, *not* doing so is surely worse than inauthenticity.

But, above all, Dresden reminds us that architecture is not, nor ever has been, about function alone.

Buildings also generate identity and can be of profound importance to those who live and work in or around them.

This is not just stone and mortar; it has meaning.

Buildings also generate identity and can be of profound importance to those who live and work in or around them.

This is not just stone and mortar; it has meaning.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter