Did a deep dive into the very early years of BYJU'S recently and made some interesting discoveries 🧵

2/10 Byju Raveendran dipped his toes in edtech as early as 2009 with his business's first website, Noesis. Noesis is a philosophical term in Greek philosophy referring to the activity of the intellect. On this site, Byju describes himself as zealous, extraordinary, and peerless.

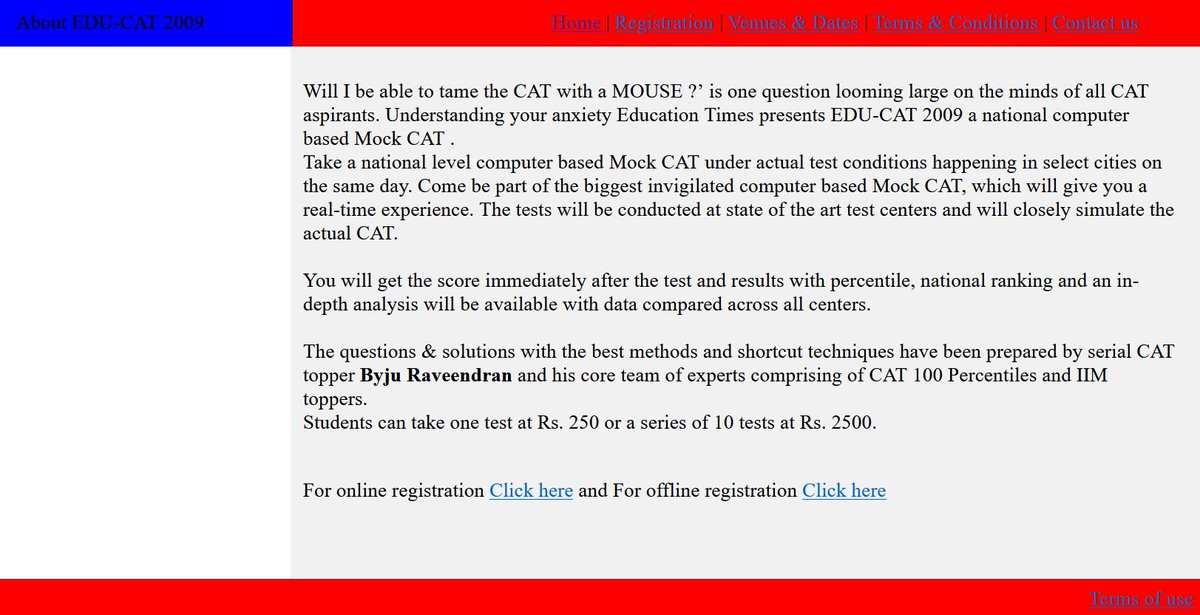

3/10 In August 2009, Noesis partnered with Times of India to offer a one-day computer-based mock CAT in major cities across India. The financial success of this experiment was formative for Byju, whose eyes were opened to the massive scope of edtech for the first time.

4/10 In the midst of all of this, peerless Byju had found an equal in one of his students: Divya Gokulnath. In her personal blog, she describes herself as a fearless rebel who lives life spontaneously. They were married in 2009 and Divya became a BYJU'S co-founder in 2011.

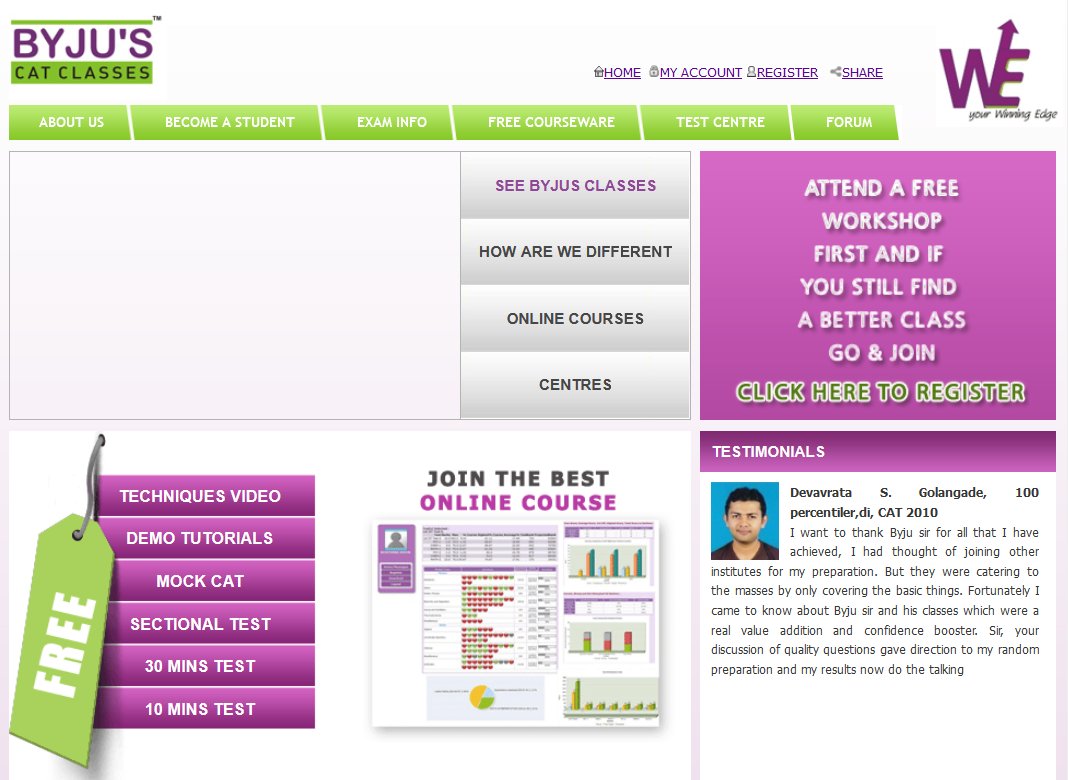

5/10 Realising that Noesis didn't roll off the tongue, in 2011 Byju rebranded the company to WE Global, WE standing for Winning Edge. By this point he had adopted a freemium model - students could take mock tests for free and if they were impressed, they could pay for classes.

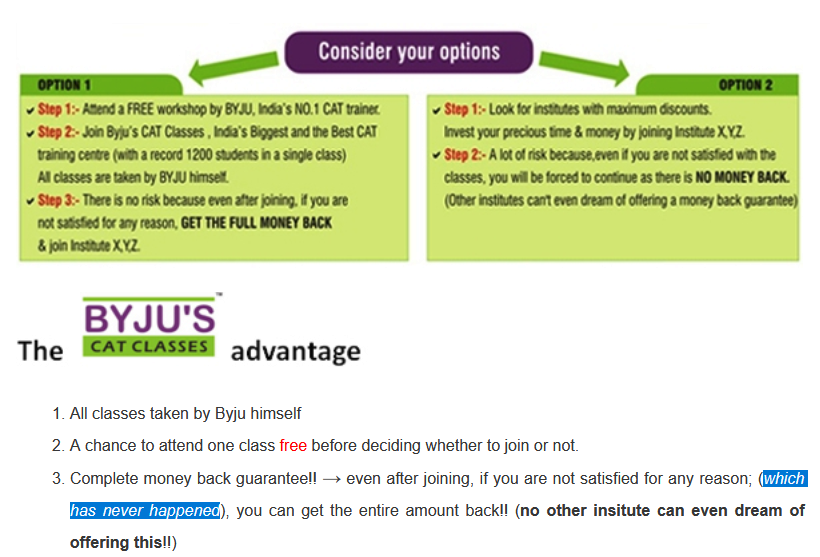

6/10 The freemium model extended to classes themselves, too. Students could take one free workshop before deciding whether or not to join, and even after joining Byju promised a full refund if the student wasn't satisfied - which had never happened, apparently.

7/10 In December of 2011, Byju made the pivot from WE Global to Think and Learn Pvt. Ltd. which is the parent company of BYJU'S today. A year later, in December of 2012, BYJU'S made the fateful decision to raise their first round of venture capital: $10M from Manipal Group.

8/10 By 2013, BYJU'S truly came into their own as an edtech company. They had already scaled their class' reach via VSAT streaming, but in 2013 they began offering their students tablets in partnership with Samsung.

9/10 They were charging ₹6,000-50,000 annually for their courses in 2013, and had brought in gross revenue of ₹14 crore.

In 2015 with the launch of their app, the company's brand name finally changed from BYJU'S Classes to the monolithic BYJU'S that it is today.

In 2015 with the launch of their app, the company's brand name finally changed from BYJU'S Classes to the monolithic BYJU'S that it is today.

10/10 Pankaj (@pankajsingh_07) and I just posted a 30+ minute video on the untold story of Noesis/WE Global/BYJU'S. You can find the full video link in my bio, but here's a sneak peek:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh