🧵 I think the 3rd Chapter of Eichah (Lamentations) describes the creation of the world of modern religious life.

Let’s learn some of it together.

Let’s learn some of it together.

For the past few years I’ve been fixated and moved by the 3rd chapter of Eichah and how it is used in later rabbinic literature to describe what contemporary religious life feels life.

We read it every Tisha B’Av because it lays the groundwork of the exilic lives we still lead.

We read it every Tisha B’Av because it lays the groundwork of the exilic lives we still lead.

Firstly, Lamentations is called Eichah (איכה). It details the feeling of mourning in the aftermath of the destruction of the first Temple.

The first 2 chapters begin with the word Eichah, which in usually translated as “Alas!”

The first 2 chapters begin with the word Eichah, which in usually translated as “Alas!”

Midrash already connect the Hebrew word איכה to the question God asks Adam after eating from the Tree of Knowledge.

Immediately after eating, God appears as a figure walking through the garden. Adam hides. God asks, “where are you?”

In Hebrew this question is אַיֶּֽכָּה.

Immediately after eating, God appears as a figure walking through the garden. Adam hides. God asks, “where are you?”

In Hebrew this question is אַיֶּֽכָּה.

If the initial exile of humanity is the story of exile from the Garden. The first detachment between the world and divinity. God first appears as Other—walking through the Garden asking, “where are you.”

Lamentations is the continuation of that question.

Lamentations is the continuation of that question.

In Genesis God asks us, “where are you?” Something has changed.

In Lamentations, we ask God.

Following the destruction of God’s home, the Jewish people now ask איכה—“God, where are you?”

In Lamentations, we ask God.

Following the destruction of God’s home, the Jewish people now ask איכה—“God, where are you?”

The destruction of the first Temple began the move away from open miracles, prophecy, and a world where divinity is tangible.

Now the world feels human-centric, devoid of Godliness.

People move through the world wondering what it’s purpose is.

Now the world feels human-centric, devoid of Godliness.

People move through the world wondering what it’s purpose is.

Which brings us to the 3rd chapter.

Something changes here.

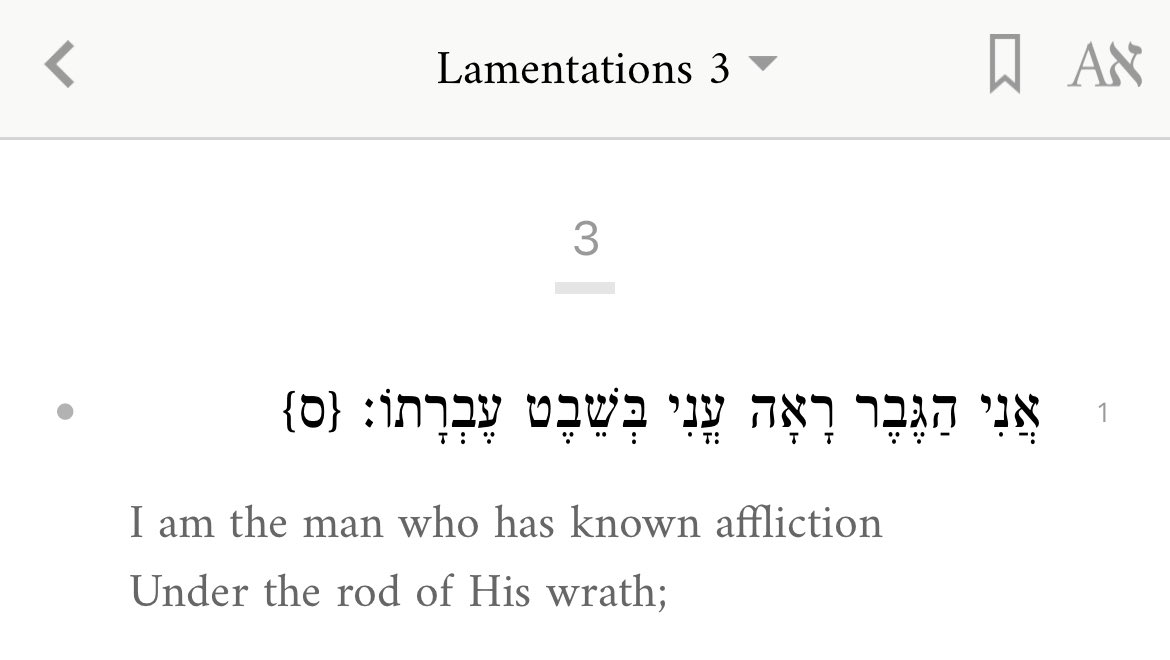

Each previous chapter begins with the word איכה. This chapter begins with the word אני — I.

The self.

Something changes here.

Each previous chapter begins with the word איכה. This chapter begins with the word אני — I.

The self.

Who is the אני, the I in this chapter? Who is the narrator?

Some say it is Jeremiah.

Ibn Ezra suggests it can be anyone.

I think it may be something even more radical.

It is the creation of the sense of self untethered from a larger identity.

Some say it is Jeremiah.

Ibn Ezra suggests it can be anyone.

I think it may be something even more radical.

It is the creation of the sense of self untethered from a larger identity.

When the Temple stood, there was a national identity that everyone was tethered to. We were all part of a nation. The feeling of being part of a people was palpable.

Now in exile we begin with I.

Isolation, an individual identity that needs to be reconstructed from scratch.

Now in exile we begin with I.

Isolation, an individual identity that needs to be reconstructed from scratch.

It’s this “I” of 3rd chapter that still hovers over the experience of modern religious life.

Feeling part of a people, our familial bonds, are frayed and not as instinctive.

We emerge in this world alone. Just an I. The loneliness of modernity.

Feeling part of a people, our familial bonds, are frayed and not as instinctive.

We emerge in this world alone. Just an I. The loneliness of modernity.

So where do we now turn to find God?

His palpable presence is gone. His home is no longer. We seem to be left with just our own ego and sense of self.

Now we need to turn within to find divinity.

God resides within אני. Within our own sense of self.

His palpable presence is gone. His home is no longer. We seem to be left with just our own ego and sense of self.

Now we need to turn within to find divinity.

God resides within אני. Within our own sense of self.

Rav Kook points out that the early prophets always spoke in terms of the collective. National responsibilities and covenants.

Rabbinic law, he explains, is all about individual obligations.

Halakha, Jewish law, nurtures the divine within the self.

Rabbinic law, he explains, is all about individual obligations.

Halakha, Jewish law, nurtures the divine within the self.

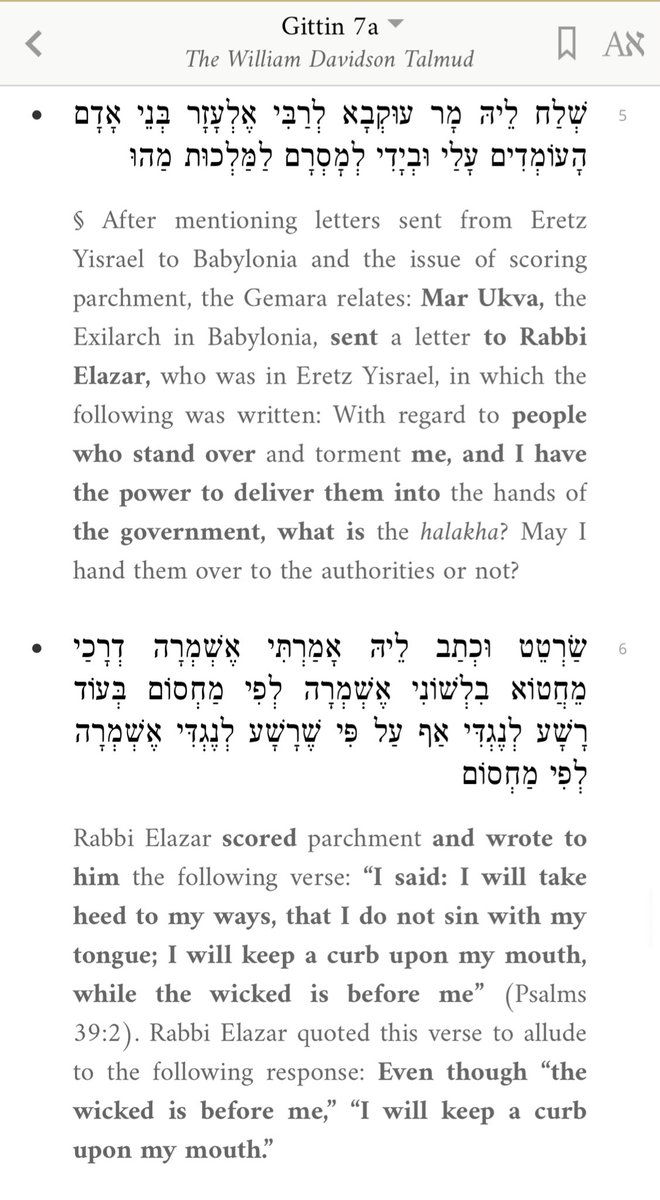

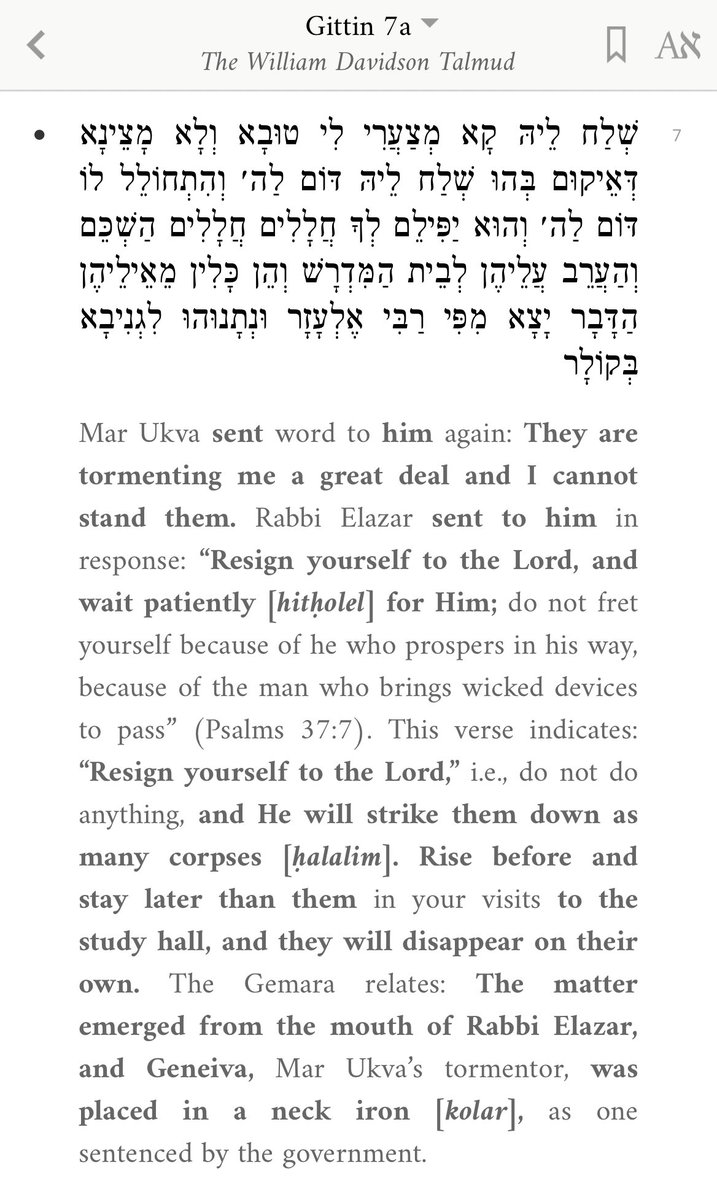

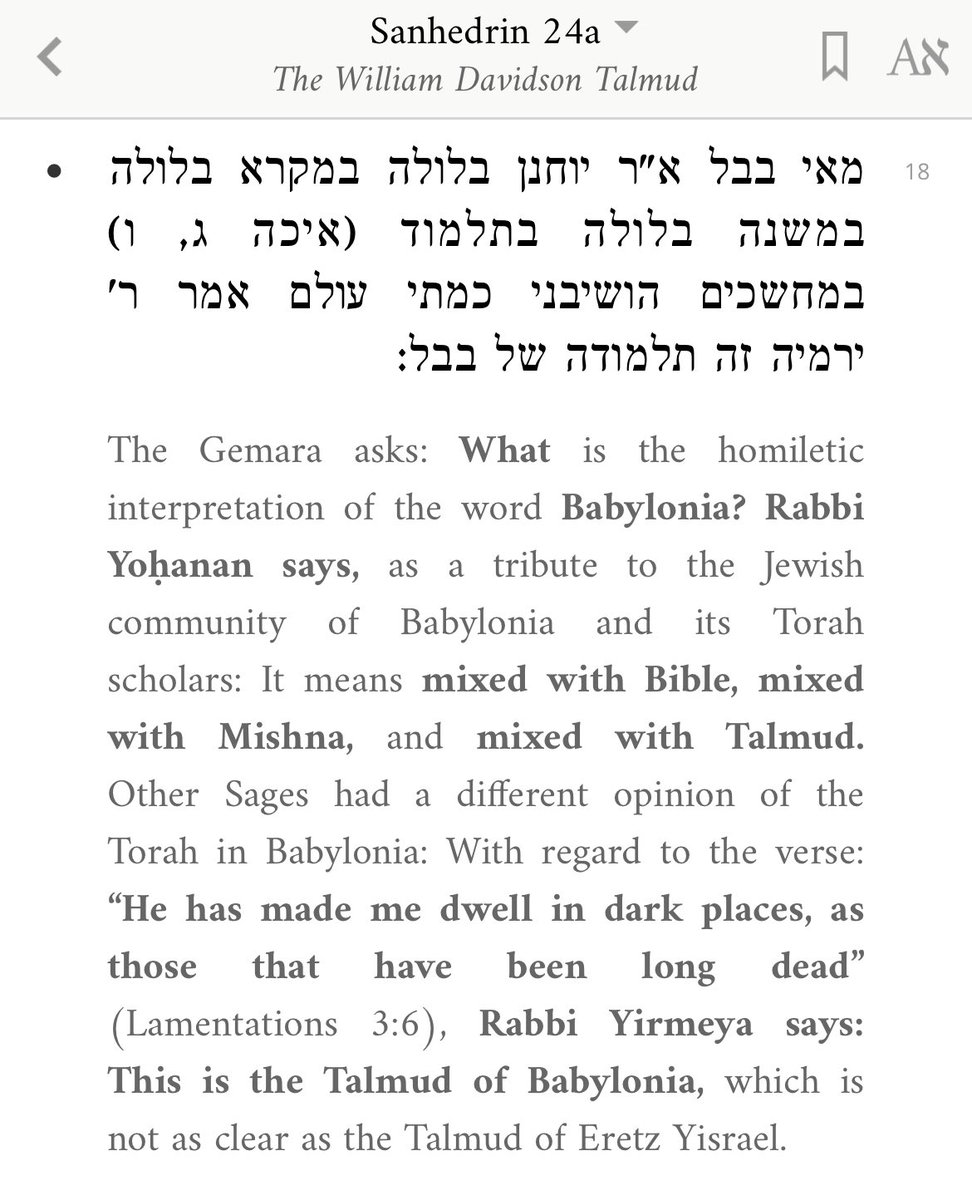

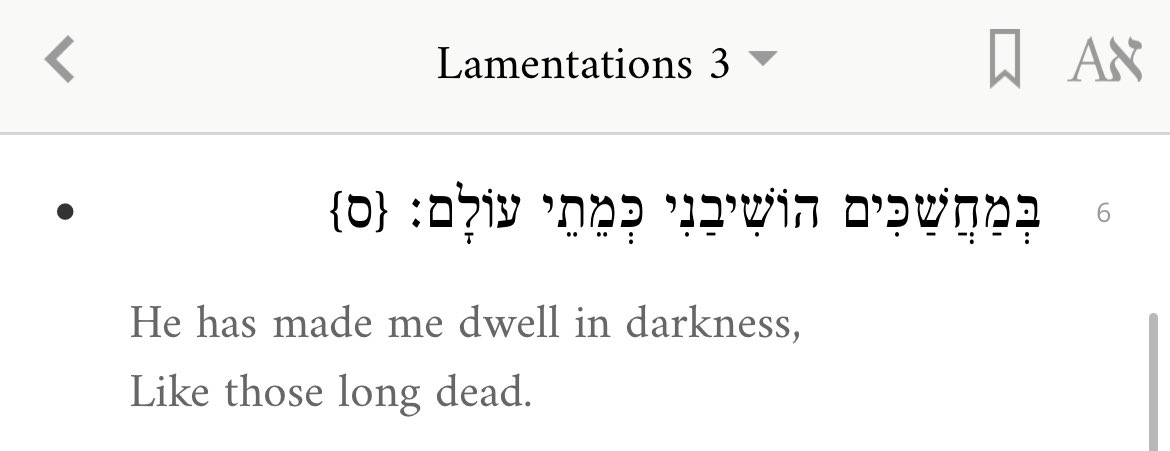

There is only one verse which the Babylonian Talmud uses to describe itself.

When looking for allusions within Tanakh for what the Talmud is all about, the Talmud turns to one place.

Where?

You guessed it. The 3rd chapter of Eichah.

When looking for allusions within Tanakh for what the Talmud is all about, the Talmud turns to one place.

Where?

You guessed it. The 3rd chapter of Eichah.

The Talmud says, want to know what we’re about?

We are addressing the feelings of darkness of death—unmoored from light and life of redemption.

The Talmud creates vision in divine darkness and life within the corpse of exile.

We are addressing the feelings of darkness of death—unmoored from light and life of redemption.

The Talmud creates vision in divine darkness and life within the corpse of exile.

Within our very own sense of self we extract divine interpretation.

The Oral Law flourishes in exile because it emerges from our interpretive powers.

The isolation of that אני, “I” brings, also plants the seeds of redemption.

The Oral Law flourishes in exile because it emerges from our interpretive powers.

The isolation of that אני, “I” brings, also plants the seeds of redemption.

Rav Tzadok says that the term אליבא דמאן דאמר, a ubiquitous Talmudic term literally meaning “according to this sage,” derives from the term לב, heart. Each of our individual hearts and experiences now are bricks in the grand edifice of the Talmud.

The Talmud becomes our homeland. It is what gathers the Jewish people from isolation, sparking conversation between distant geographies and generations.

A Temple is rebuild through the divinity that resides within each of us.

We are the bricks.

A Temple is rebuild through the divinity that resides within each of us.

We are the bricks.

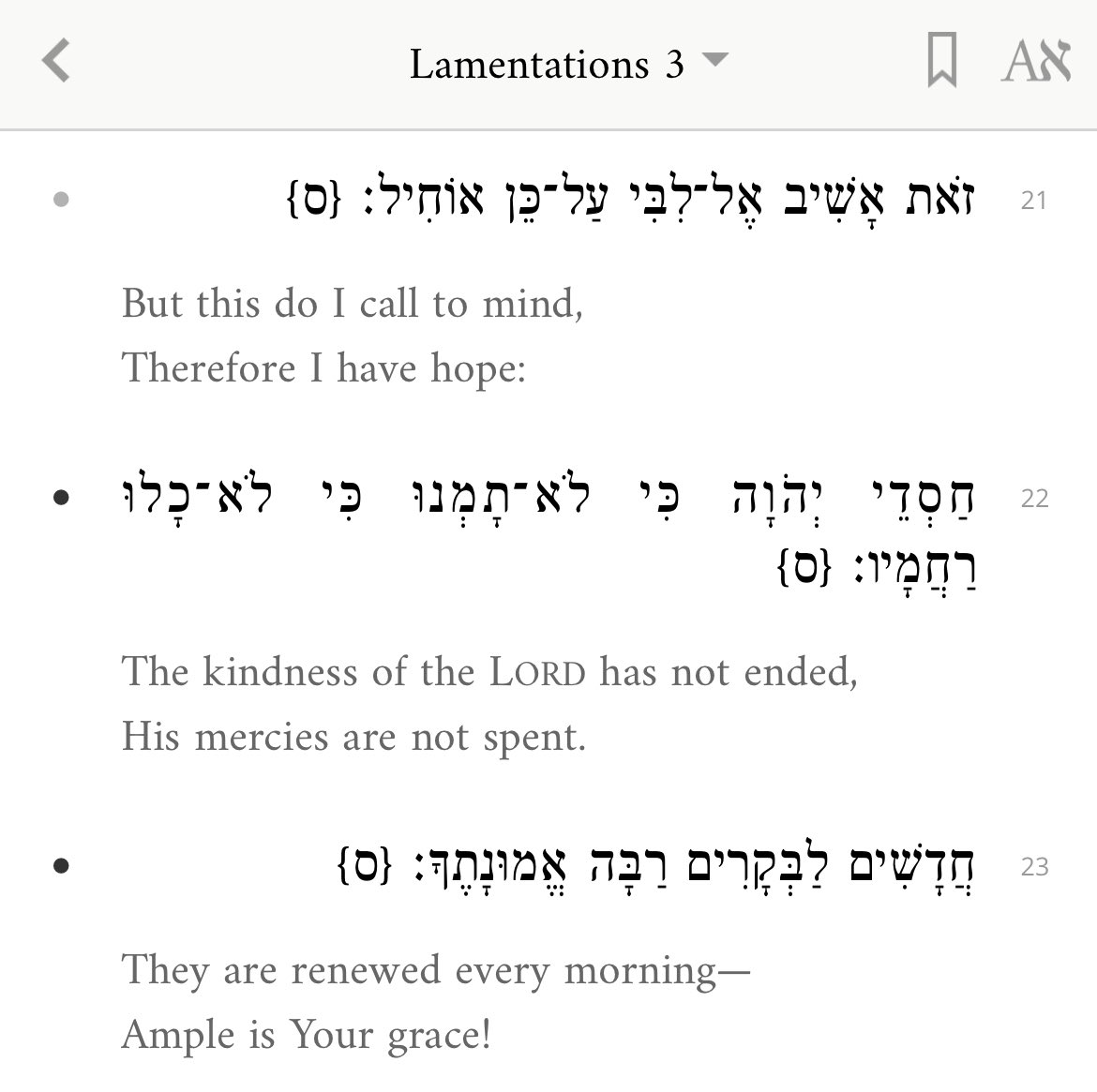

Suddenly in the middle of the 3rd chapter, it becomes optimistic. Hope is found within darkness.

We find a response to the pain of exile.

We find a response to the pain of exile.

The answer lies within us.

It doesn’t come through prophecy or a miracle. But, as Rashi explains, through an inner conversation we have with ourselves.

It is the realizing the God is still here. Just not in the Temple but within our own interiority.

The response is us.

It doesn’t come through prophecy or a miracle. But, as Rashi explains, through an inner conversation we have with ourselves.

It is the realizing the God is still here. Just not in the Temple but within our own interiority.

The response is us.

We’re comforted that God’s kindness never ended.

The Vilna Gaon points out that of the three pillars of the world, Torah, Avodah, and Chessed—the only one that is unchanged following exile is Chessed, kindness.

The Vilna Gaon points out that of the three pillars of the world, Torah, Avodah, and Chessed—the only one that is unchanged following exile is Chessed, kindness.

We no longer have Avodah the same way, there’s no service in the Temple.

We no longer have Torah the same way, there’s no centralized Sanhedrin.

But we still have kindness. Because *we* — each אני, each i remains a messenger, a שליח נאמן, a faithful agent to bring kindness… twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

We no longer have Torah the same way, there’s no centralized Sanhedrin.

But we still have kindness. Because *we* — each אני, each i remains a messenger, a שליח נאמן, a faithful agent to bring kindness… twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

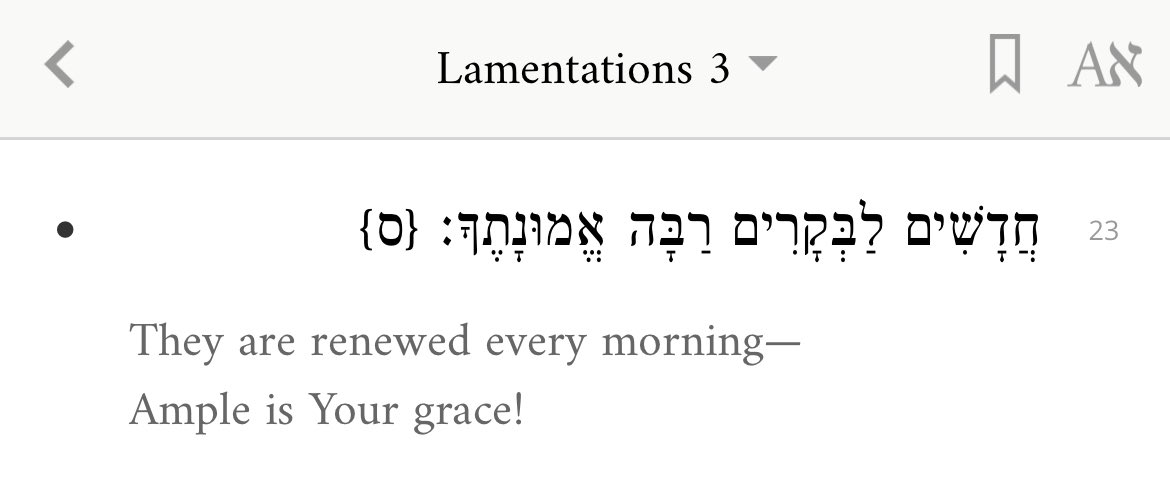

And that is why this optimistic turn in the 3rd chapter ends with רבה אמונתך, great is God’s faith.

God’s faith!?!

What does God believe in?

God believes in us. God believes we can still find divinity within our own internal exilic lives.

God has faith in אני, in me.

God’s faith!?!

What does God believe in?

God believes in us. God believes we can still find divinity within our own internal exilic lives.

God has faith in אני, in me.

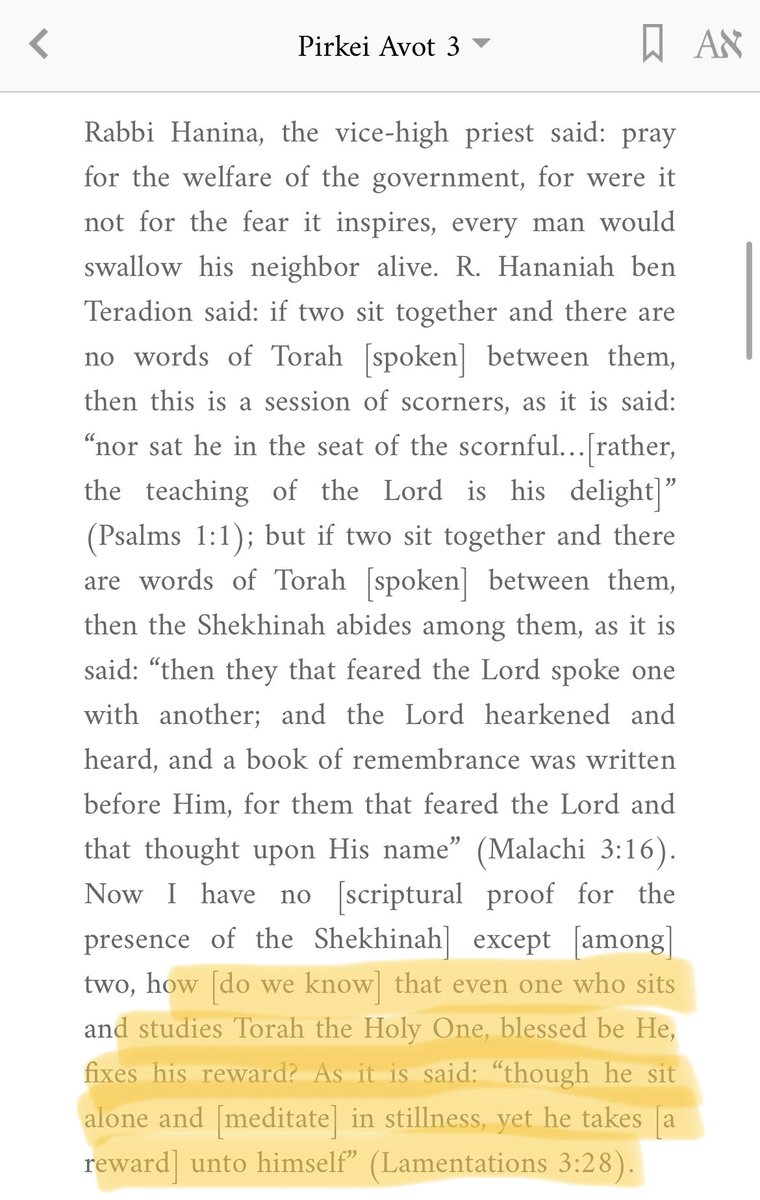

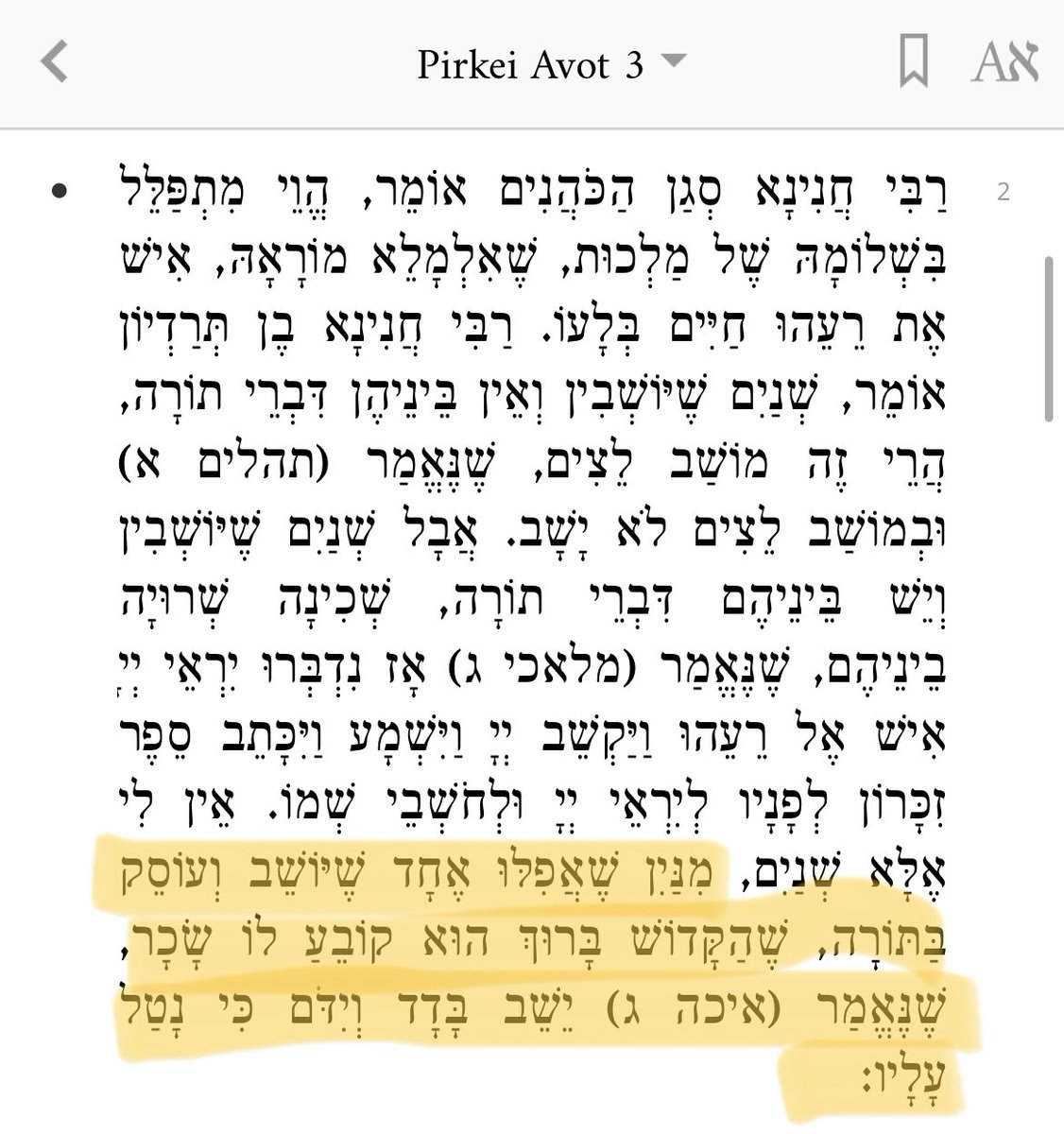

Perhaps that’s why when the Mishnah wants to know about how we can find divinity when studying Torah by ourselves—alone—it again turns to the 3rd chapter of Lamentations.

Even alone, we can find Godliness.

Even by ourselves, we can join the collective conversation of Talmud.

Even alone, we can find Godliness.

Even by ourselves, we can join the collective conversation of Talmud.

And so each morning we begin with the affirmation of the reality that the 3rd chapter of Eichah describes.

מודֶה *אֲנִי* לְפָנֶיךָ מֶלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּם, שֶׁהֶחֱזַרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי בְּחֶמְלָה, *רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶךָ*:

God has faith in us

❤️🩹

מודֶה *אֲנִי* לְפָנֶיךָ מֶלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּם, שֶׁהֶחֱזַרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי בְּחֶמְלָה, *רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶךָ*:

God has faith in us

❤️🩹

Much if these ideas are expressed through our most recent episode of @18_forty.

https://twitter.com/18_forty/status/1683941798119370752

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter