Back to the culture, part X: last time I promised I had a few more millet threads in me, and unfortunately that is the case. Let’s keep our finger on the pulse with a new thread on one of the last major millet crops: finger millet!

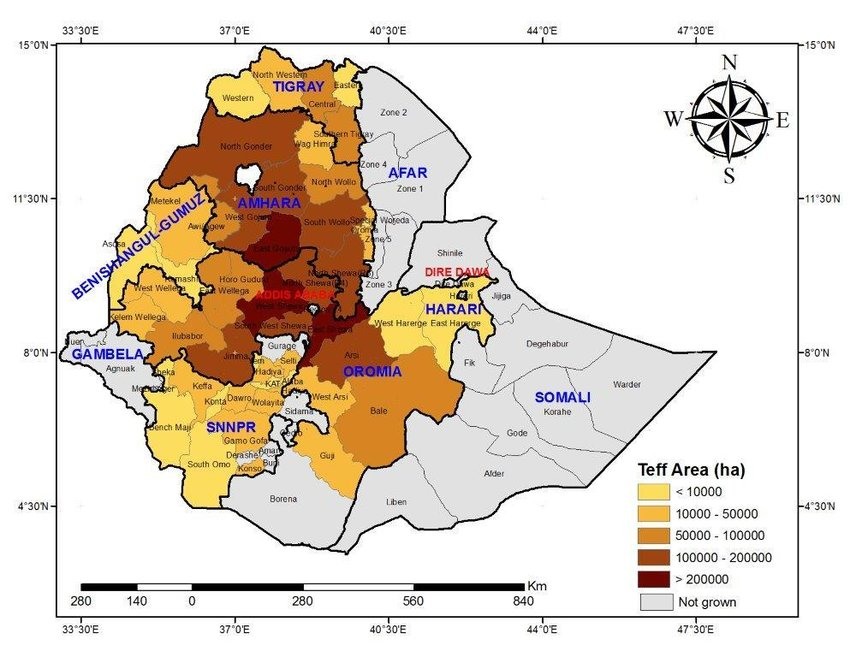

My previous millet thread was on the topic of t'ef, the strange tiny-grained crop exclusive to the horn of Africa:

https://twitter.com/General_JWJ/status/1671130436259438592

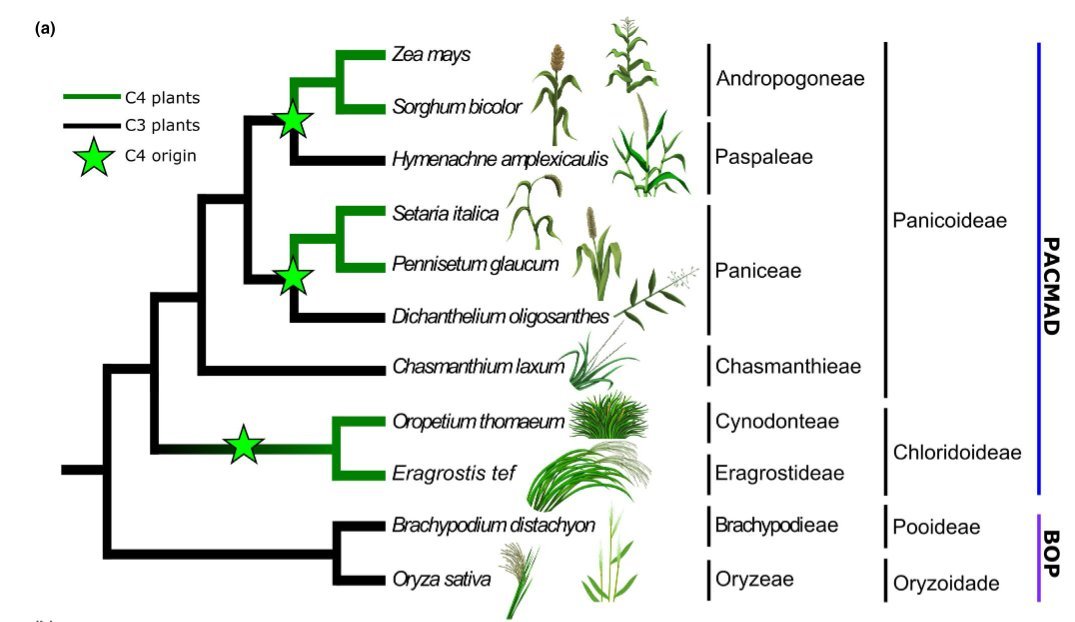

Its Latin name is Eleusine coracana. Like the other African-originating millets it’s a bit of an outlier, belonging to the subfamily Chloridoidea like t’ef, but to the tribe Cynodontidae, of which it’s the only cultivated plant

As this group, along with that of t'ef, independently developed C4 photosynthesis, it's extremely well equipped to survive dry, hostile environments where other plants would wither and die

https://twitter.com/General_JWJ/status/1671130450847309826

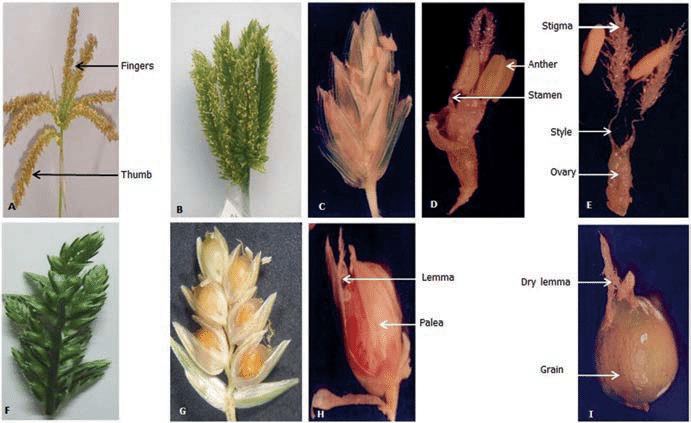

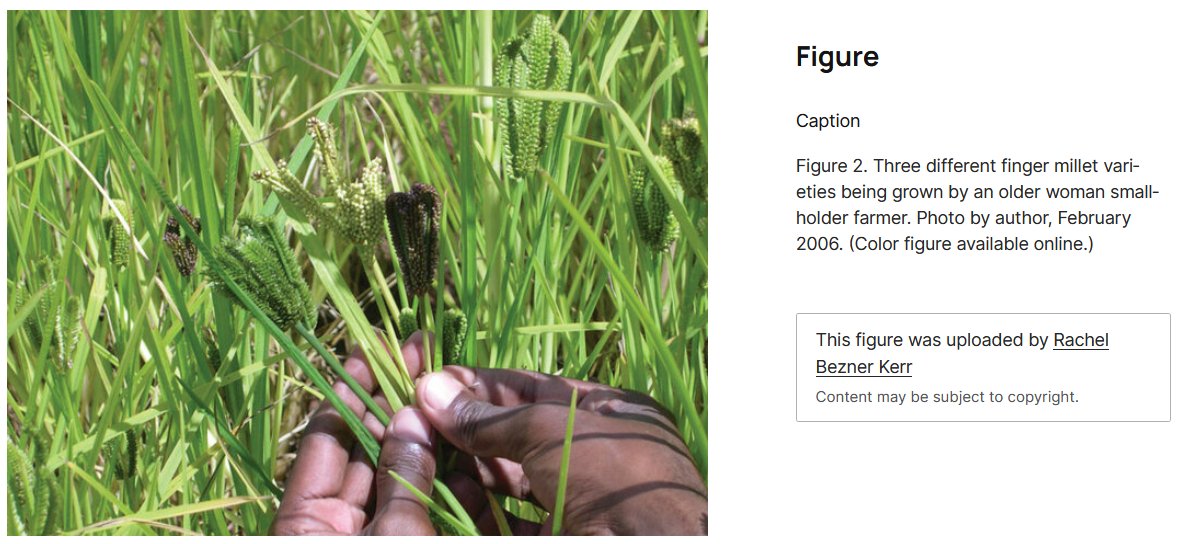

Its common name finger millet comes from the shape of its inflorescences: dense panicles of small floral spikes that become covered in grains after fertilisation and are warped into a bent shape by the press, looking like the clutching fingers of a strange hand

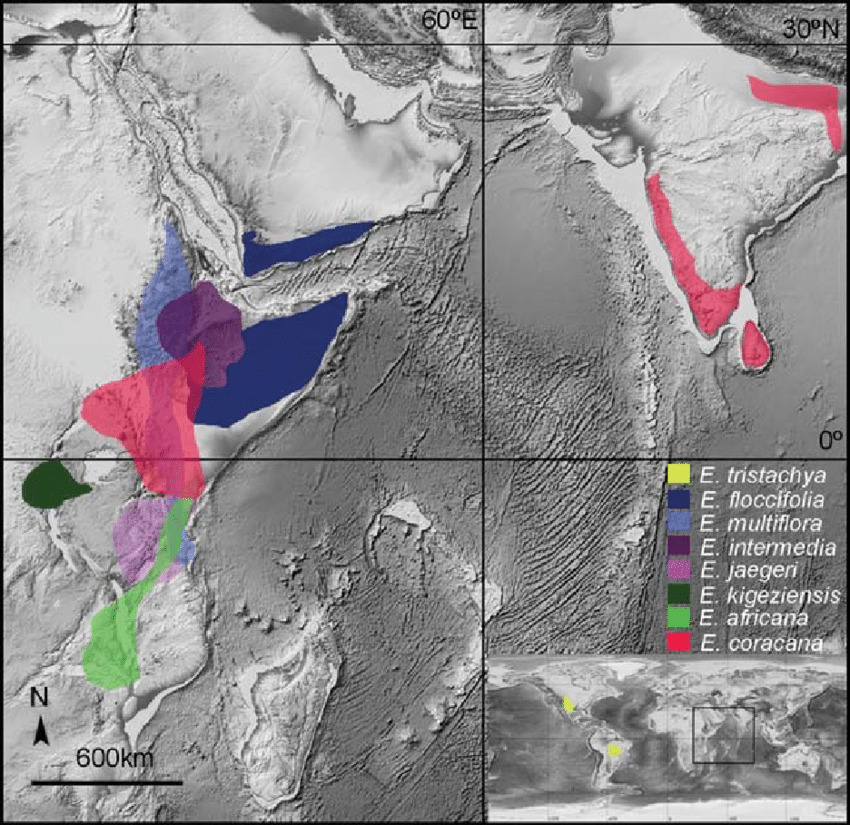

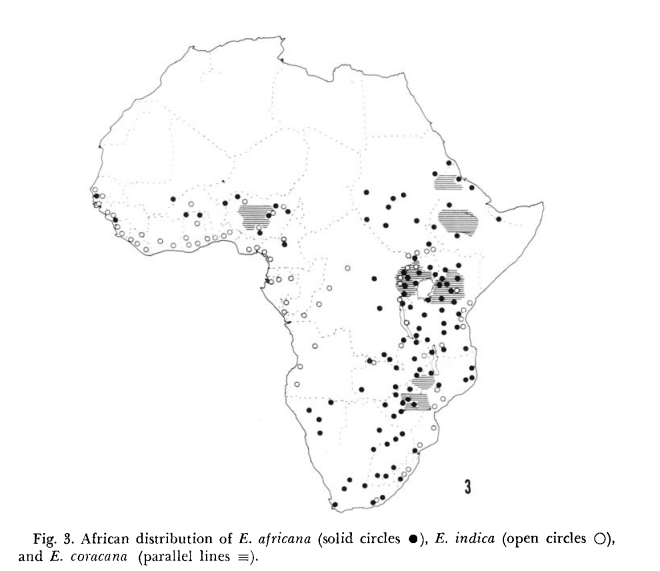

The genus Eleusine is a pantropical (and subtropical) one containing 10 species centered in Africa. Among these is E. Africana, the wild ancestor of finger millet. Its current distribution is centered around Lake Malawi, with a corridor along the Tanzanian and Kenyan coast

The millet itself is a small annual plant which is self-pollinating. This born survivor is able to grow in high altitude, low nutrient and low moisture environments, even through extended droughts. Its grains also have an unusually long shelf-life

The cereal also has an excellent nutritional profile (we’ll get back to it) and is an excellent fodder for livestock. It’s currently ranked as the fourth most grown millet in arid regions after the “coarse grained millets” (pearl, sorghum) and the “minor millet” foxtail

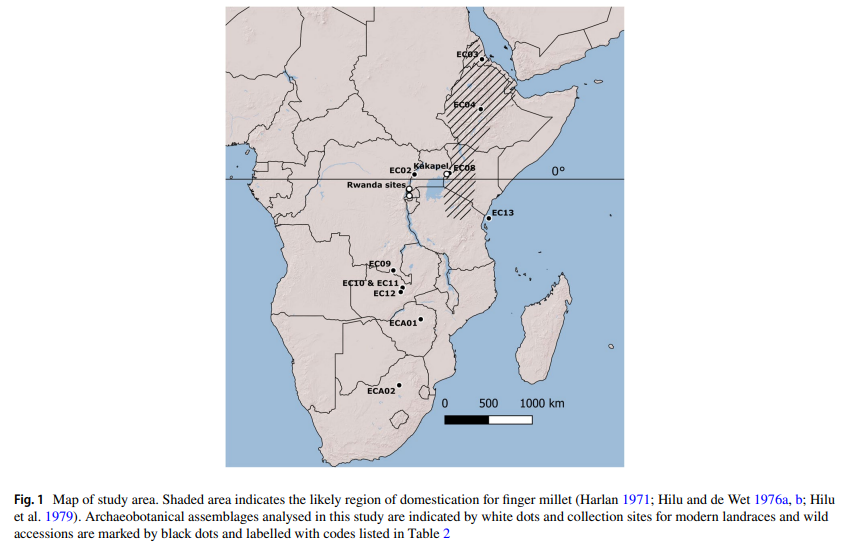

This crop’s domestication is particularly mysterious, as very little archeobotanical data was ever found. It’s currently believed the area it was domesticated in lies somewhere in the highlands between lake Victoria and the shores of Eritraea

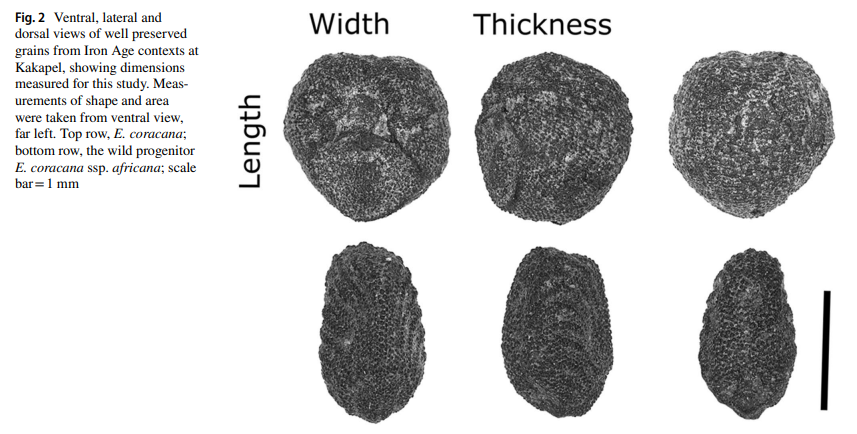

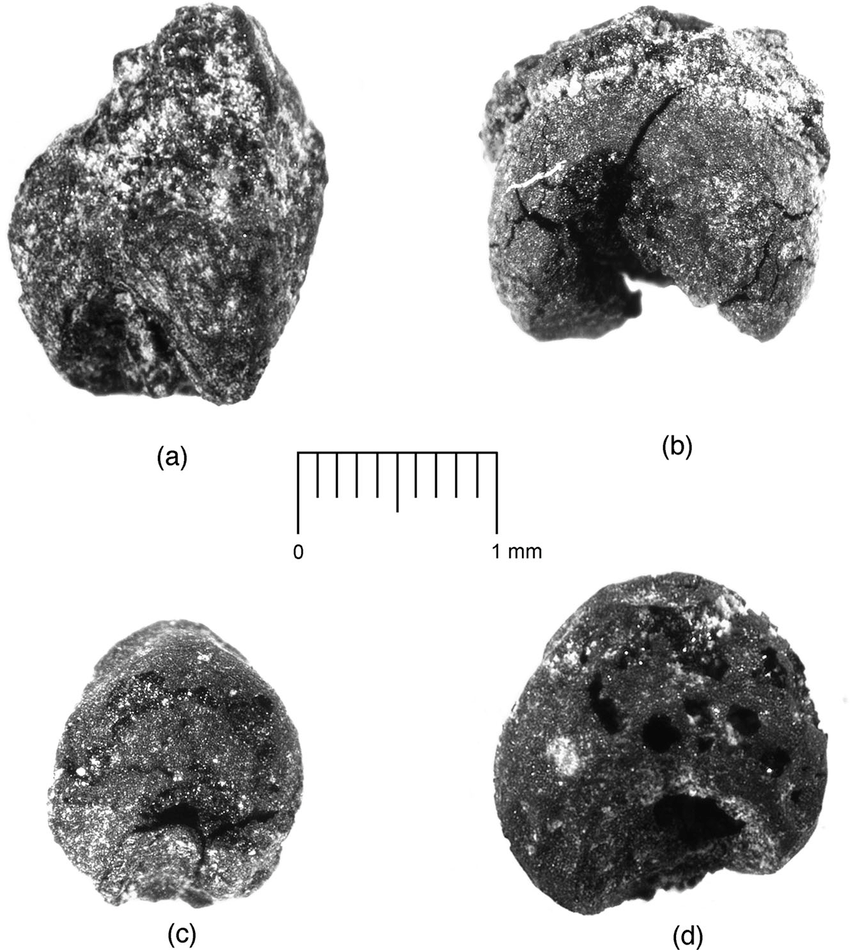

Its seeds were never collected in large enough amounts to study their evolution over time, as characteristics of the size, shape, bran thickness and texture and starch content of grains can help guess when selective pressure for yield were applied over time

The oldest confirmed African trace is partial & burnt, believed to date to the Aksumite period (0AD). A claimed 3rd mill BC stash was uncovered in Gobedra cave, but C14 analysis revealed it to be younger (800ish AD)

https://twitter.com/General_JWJ/status/1671130479368478721

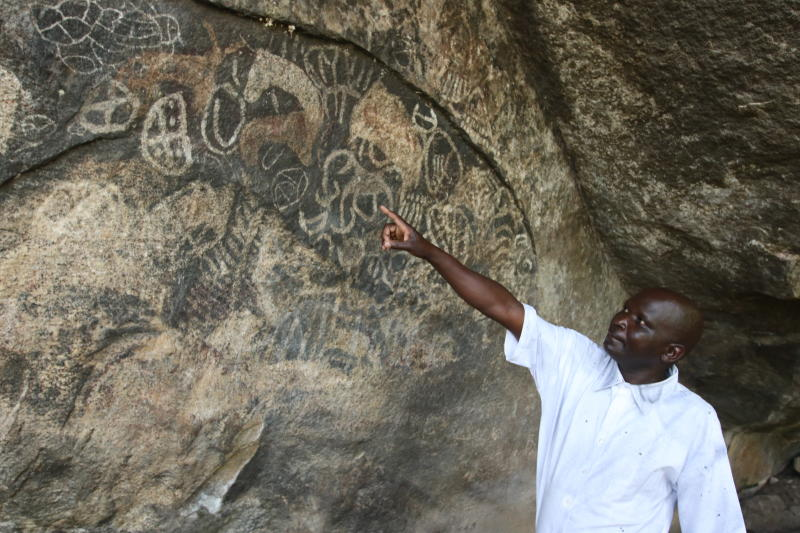

A few seeds were found within Aksum itself and are dated to 600-800AD. Outside of Ethiopia, finds occurred with uncertain dating at Gogo falls (lake Victoria), associated with pre-iron age Kansyore pottery, and in a pastoralist site (700-1000AD) within Kenya’s central Rift Valley

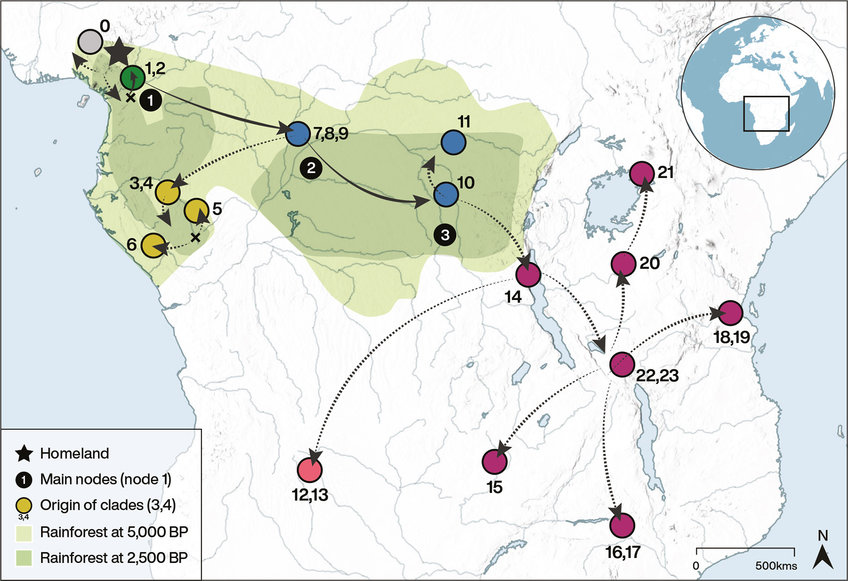

Interestingly, this last site is also the first one where genetic markers of Bantu ancestry (West African) were found within East Africa.

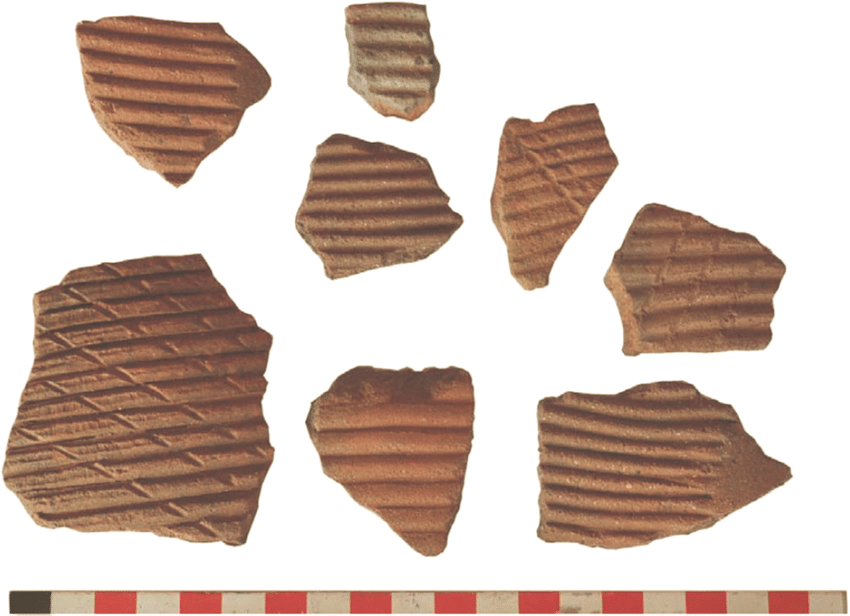

A few older finds in South Eastern Sudan are much older, but it’s doubtful whether these are cultivated, or gathered wild specimens. They’re grain & chaff impressions on potsherds from 3500 BC-0 AD from Jebel Morkam & Mahal Teglinos

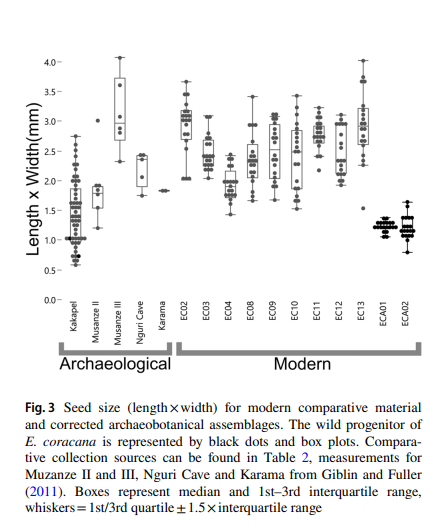

Seeds also turned up at iron age sites in Rwanda dating between 600-1200AD and in a late iron age context on the Southern Kenyan coast as well as Indian ocean islands such as Pemba and Comoros. The largest find of seeds is from Kakapel, W Kenya, 1100-1300AD

What’s far more interesting is that seeds were found in Indian archeology which date to 2000 BC. Furthermore Indian landraces are closer to the lowland East-African ones than the highland ones. As the plant’s believed to have been domesticated in the highlands,

Current theory: the crop was domesticated centuries earlier so it had time to differentiate between highland & lowland landraces, which were then spread Eastwards, at the same time as pearl millet & sorghum

https://twitter.com/General_JWJ/status/1636758522988724224

In any case, the paltry amount of finds in African contexts, all dated to the “common era”, indicate a preservation bias. Researchers found the seeds have a far lower temperature tolerance range before burning and crumbling away compared to other seeds from these areas

There is also a huge variability in size & shape for seeds of this plant compared to other crops, indicating that different varieties may have had different uses (such as baking, brewing, fodder, etc)

Today the crop is grown mostly in East-Africa and throughout India, with an average yield of 1 ton per hectare and a total cultivated area of approximately 4.5-5 million hectares. This is evenly split between Africa and India

It’s able to grow from sea level up to 2400m of altitude, and comes in short (75 days) and long lived (160 days) varieties which respectively grow well in dry highland areas and in well-irrigated plains. The ideal irrigated yield is about 5-6 T/ha

While the plant itself is non-shattering, like all domesticated cereals, fields are easily invaded by wild Eulisine which aren’t easy to recognize in the early stages, until their floral spikes shatter naturally after fertilisation, leaving a smaller yield overall

Nutritionally it’s one of the richest in calcium, iron, lysine and methionine among cereals as well as vitamins such as riboflavin, thiamine, niacin… It’s also gluten free and has a low glycemic index. This has prompted its classification as a superfood, like other millets

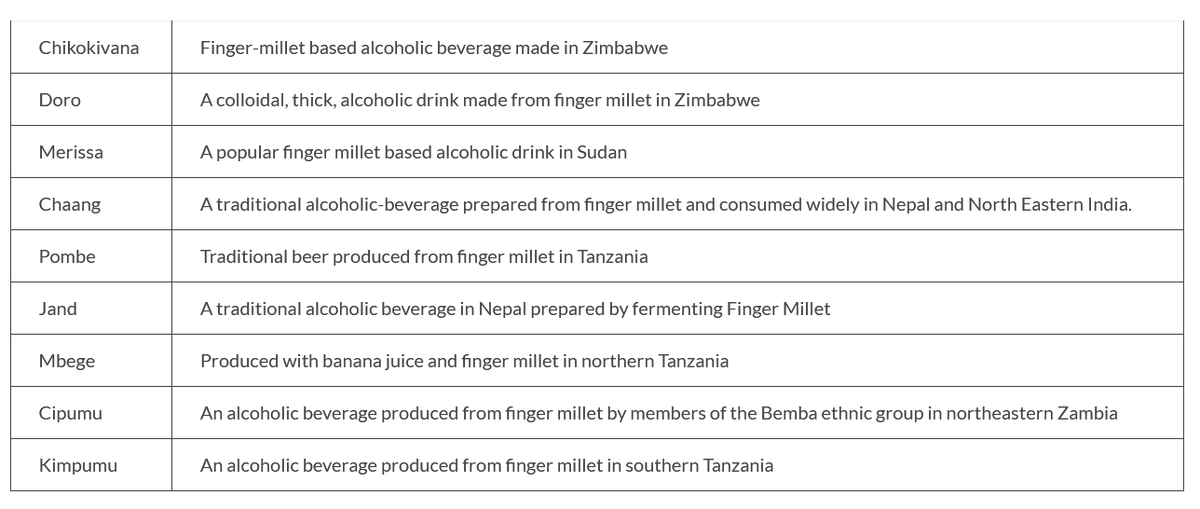

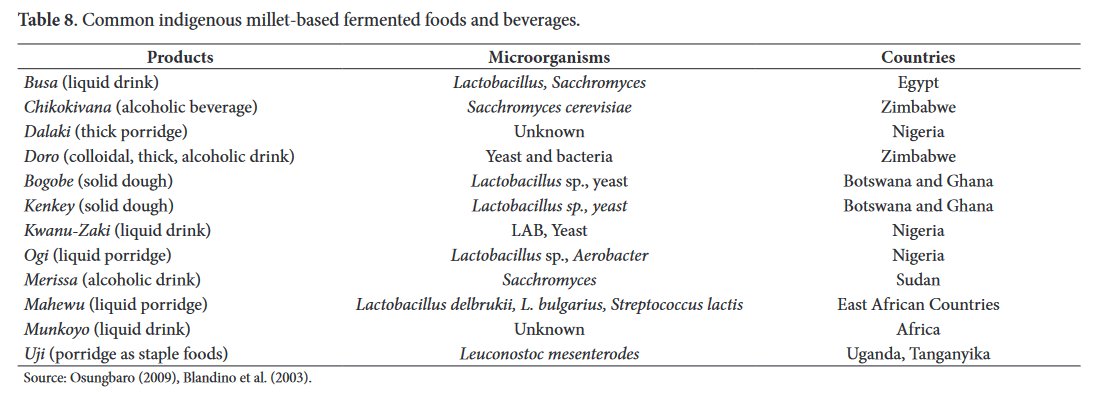

As it’s an orphan crop grown for local consumption only, most items derived from it are limited to local cuisine rather than commercial goods. However there are several alcohols & drinks using finger millet grains as a main ingredient, both in Eastern Africa and Southern Asia

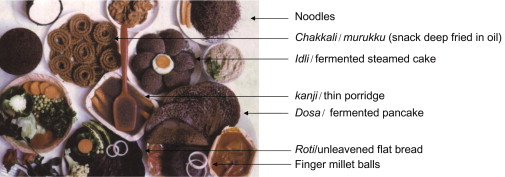

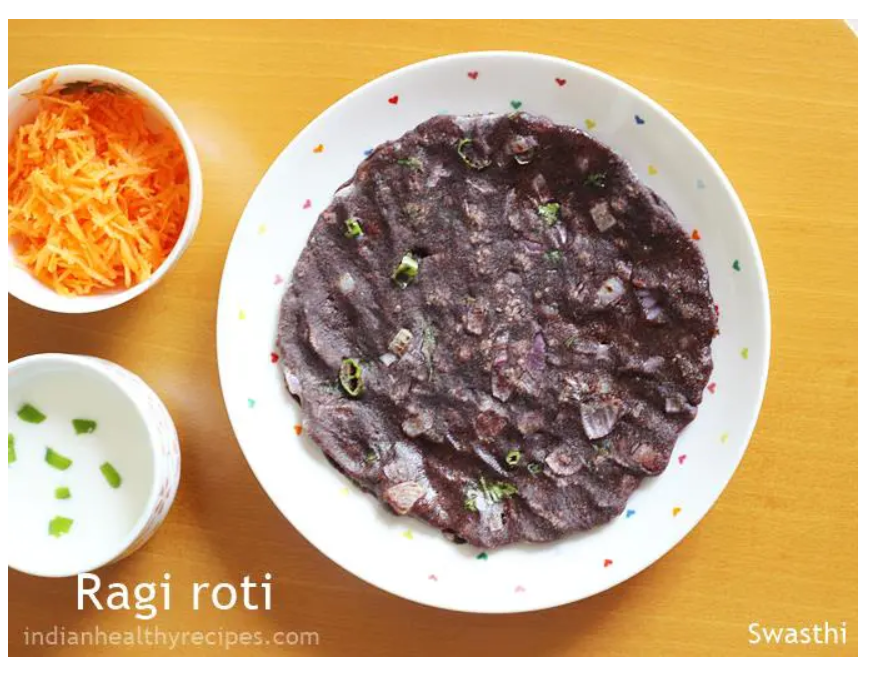

It’s also frequently ground into flour which is used to make porridges (especially a nutritive weaning porridge for young children), soups, or baked goods such as leavened or flatbreads, biscuits and sweet or savoury dough balls. It can also be extruded into pasta or noodles

Overall this is a small crop with lots of scope for growth and discovery even though the dishes derived from it aren't so well known right now. Its survivability and long shelf-life mean developing it could be key in alleviating food insecurity in arid countries

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter