With all the buzz about #LK99 and the possibility of a room temperature superconductor, let's have a topical thread.

Can a superconducting induction coil make the perfect battery?

And is it world changing? Read on...

Can a superconducting induction coil make the perfect battery?

And is it world changing? Read on...

The introduction of Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) into our power grids has had a number of effects, but prime among them is a massive increase in capacity variability, which electric grids must then adjust to.

Hence the recent spike in interest in grid-level energy storage.

Hence the recent spike in interest in grid-level energy storage.

Electrical energy can be stored in many ways: Electro-chemically with batteries, through kinetic energy with flywheels, gravitational potential with pumped hydro, through compressed air etc. All have pros & cons.

You can also store energy in a magnetic field...

You can also store energy in a magnetic field...

Spooky but true. Feed DC current into a superconducting inductor and you store energy, practically lossless, through the induced magnetic field, and recoup that energy by discharging the coil.

This works with superconductors: Anything else will lose energy in milliseconds.

This works with superconductors: Anything else will lose energy in milliseconds.

Why? Pass a current through an incandescent light bulb and touch it. Once you've sucked your fingers, note where all that electrical energy went: Into heat through resistance in an imperfect conductor. Try to store energy in a copper magnet coil and you'll get the same thing.

Superconductors are different. The practically zero electrical resistance allows long term storage, so long as the magnetic field is contained and not inducing motion or current elsewhere. Round trip efficiencies are ~95%, and most of the 5% loss is the AC-DC inverter/rectifier.

Superconducting Magnet Energy Storage (SMES) isn't just hyper efficient: It also has very high specific power (10-100,000 kW/kg) and an almost instantaneous ramp. They can also fully discharge near infinitely without degradation.

There are some drawbacks, but later...

There are some drawbacks, but later...

... Firstly, toroidal or solenoid design? You can coil a SMES two ways: The solenoid is easier to manufacture but the toroid produces lower mechanical strain from the magnetic fields. In practice, this means solenoids work well for small installations, toroids for big ones.

These magnetic fields are serious: A commercial non-research hospital MRI scanner can sustain magnetic fields of up to 3 tesla. There are videos showing what that can do.

Superconducting magnets can top out at well over 20T. This creates a structural design limitation...

Superconducting magnets can top out at well over 20T. This creates a structural design limitation...

Lorentz forces on moving charges ensure that magnetic storage systems will be exposed to significant stress loading, and this limits their ultimate potential: If we assume a reasonable 100MPa structural maxima, then specific energies in our magnet are limited to 12kJ/kg.

The CMS magnet in the LHC supercollider reached 11kJ/kg, so 12kJ is a decent hypothetical maximum, and it's not much. It's higher than pumped hydro, but not by enough, and, unlike pumped hydro, SMES kgs are expensive.

High specific power, low specific energy. Fast but feeble.

High specific power, low specific energy. Fast but feeble.

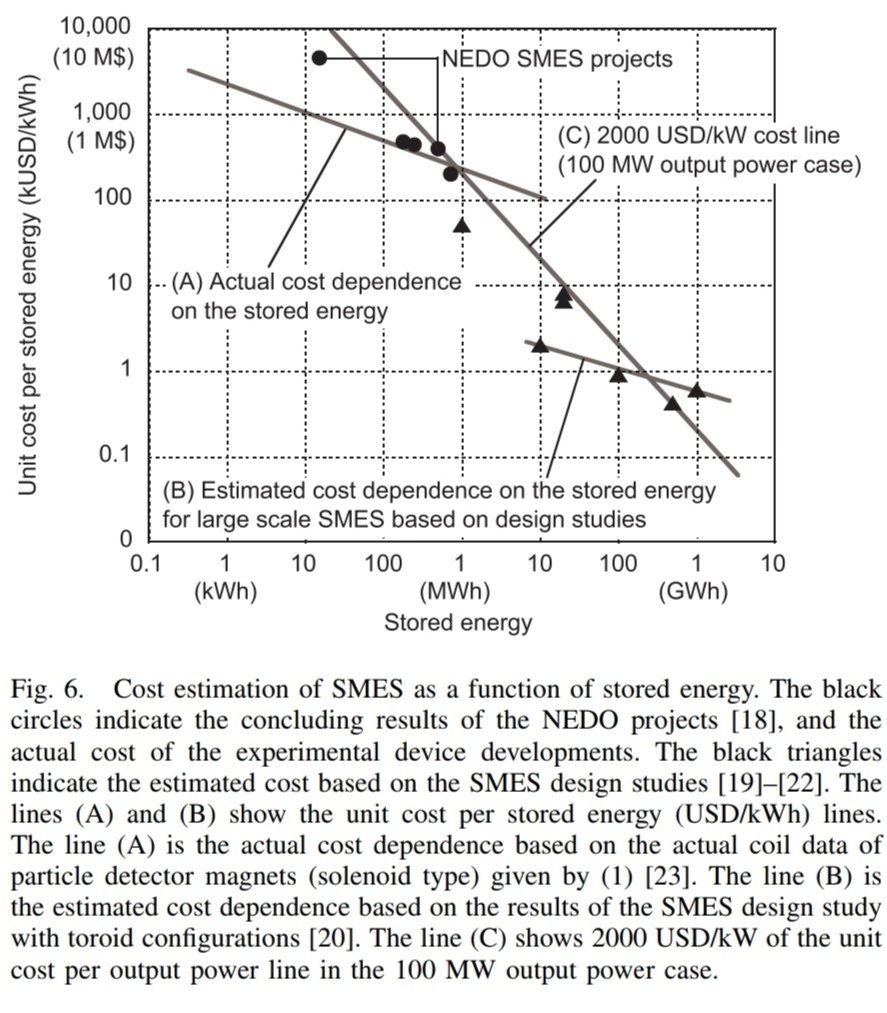

So for this reason plus the need for cryogenics, and huge expense, SMES has been a small niche and only a scattering of systems exist, managing voltage sags, oscillation smoothing and in fusion & particle physics research. Long period power smoothing has not been tried with SMES.

But what if it was?

The world's largest battery storage array is Vistra Moss Landing Facility in California. It can store 1.6GWh and a max power of 400MW. Average costs are ~$1B/GWh.

What of SMES?

The world's largest battery storage array is Vistra Moss Landing Facility in California. It can store 1.6GWh and a max power of 400MW. Average costs are ~$1B/GWh.

What of SMES?

Current experimental installations are more expensive by several orders of magnitude, though there is potential for truly large scale implementation to bring costs down to parity through mass production. Lower still if new superconducting materials favour mass production.

That's a big if. An additional issue is land use: A hypothetical 1GWh SMES would have a torus diameter in the 100m-500m range, which is not subtle, but manageable. Cost is the primary issue: Superconductor material first, cryogenics second.

Room temperature ambient pressure superconductors, if discovered and mass produced, could make it a plausible utility scale storage system, and with this we return to LK-99, but let's not be too optimistic. We need to multiply scale by orders of magnitude & reduce cost the same.

So as with so many things, if it happens and the hype around LK-99 becomes reality, SMES will be an evolution, not a revolution. The perfect battery remains imperfect for the time being.

Sources attached, all free downloads. I hope you enjoyed this!

Sources attached, all free downloads. I hope you enjoyed this!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh