What is modern architecture?

In some sense modern architecture is whatever we're building right now — if by modern we mean "present day".

In which case every single building was once a work of modern architecture, even the Pyramids and the Coliseum...

In some sense modern architecture is whatever we're building right now — if by modern we mean "present day".

In which case every single building was once a work of modern architecture, even the Pyramids and the Coliseum...

And so it's worth noting that modern architecture — new architecture — has always been controversial.

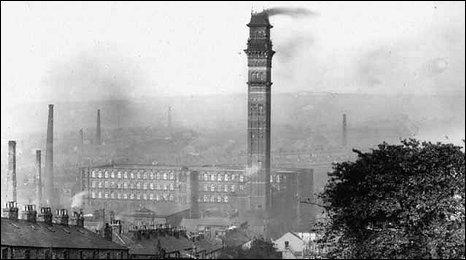

We might think, looking at the buildings of 19th century Britain, which are now generally regarded as pleasant and even beautiful, that everybody at the time also felt that way.

We might think, looking at the buildings of 19th century Britain, which are now generally regarded as pleasant and even beautiful, that everybody at the time also felt that way.

But... they didn't.

Now beloved and iconic buildings like St Pancras Station and Tower Bridge were both lambasted as artificial, ridiculous, ugly, offensive, and much worse.

London's National Gallery was regarded as a public disgrace — partly because its dome was so small.

Now beloved and iconic buildings like St Pancras Station and Tower Bridge were both lambasted as artificial, ridiculous, ugly, offensive, and much worse.

London's National Gallery was regarded as a public disgrace — partly because its dome was so small.

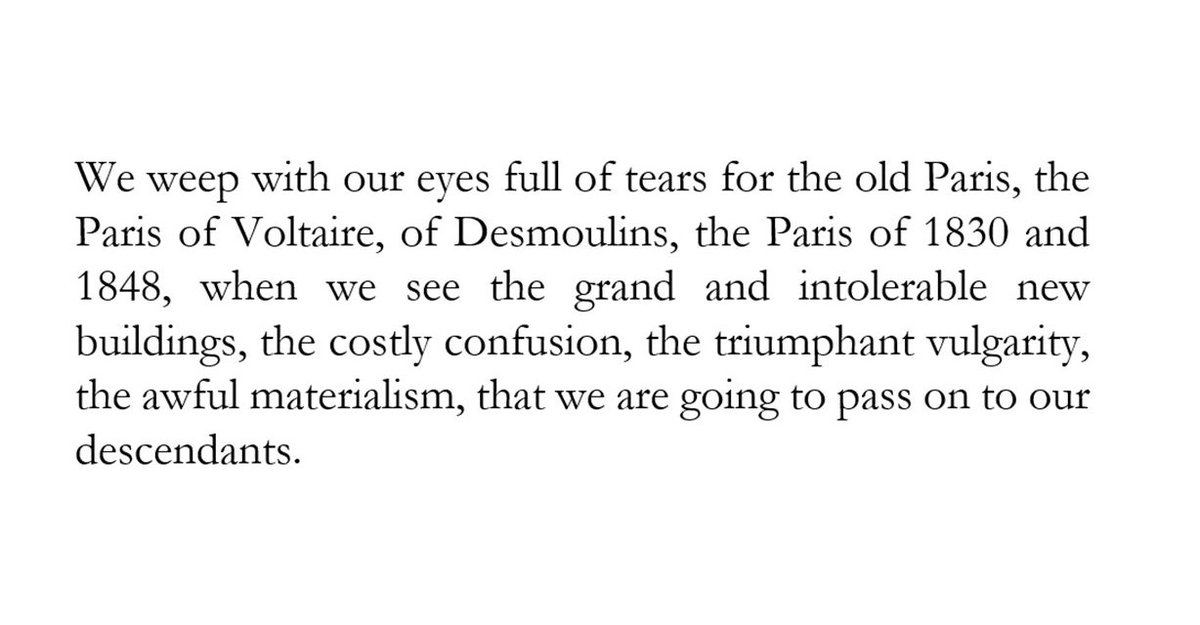

Take Paris, which was totally rebuilt during the 19th century, as its Medieval streets were torn up and replaced by the boulevards of Baron Haussmann.

People love Paris now, but people at the time hated how it was being transformed. This is what the mayor, Jules Ferry, said:

People love Paris now, but people at the time hated how it was being transformed. This is what the mayor, Jules Ferry, said:

All that architecture once regarded as ugly is now largely adored... why?

Well, it is revealing to think about architecture in terms of Age rather than Style.

Is the Pantheon beautiful, or is it just old? Would a modern recreation be equally admired?

Well, it is revealing to think about architecture in terms of Age rather than Style.

Is the Pantheon beautiful, or is it just old? Would a modern recreation be equally admired?

Or, to flip that around, think of something like I.M. Pei's glass pyramid in front of the Louvre — which was and remains controversial

Imagine that it was one hundred, five hundred, or even one thousand years old.

Does it suddenly seem more interesting, more characterful?

Imagine that it was one hundred, five hundred, or even one thousand years old.

Does it suddenly seem more interesting, more characterful?

Nobody has expressed this peculiar fact better — of how age alone transforms a building into something *more* than its appearance, more than its stone and mortar — than the 19th century writer John Ruskin.

Perhaps age will one day make all modern architecture beautiful?

Perhaps age will one day make all modern architecture beautiful?

Of course, modern architecture does have a more precise meaning than merely "new".

It refers to a specific set of construction methods and aesthetic features which have come to dominate the world in recent decades and has, indeed, become the dominant global style...

It refers to a specific set of construction methods and aesthetic features which have come to dominate the world in recent decades and has, indeed, become the dominant global style...

When Modern Architecture with a capital M first began is a matter of debate.

From a stylistic point of view its origins may go right back to the 18th century, when Neoclassical architects like Jacques-François Blondel advocated for simpler, geometric, functional architecture.

From a stylistic point of view its origins may go right back to the 18th century, when Neoclassical architects like Jacques-François Blondel advocated for simpler, geometric, functional architecture.

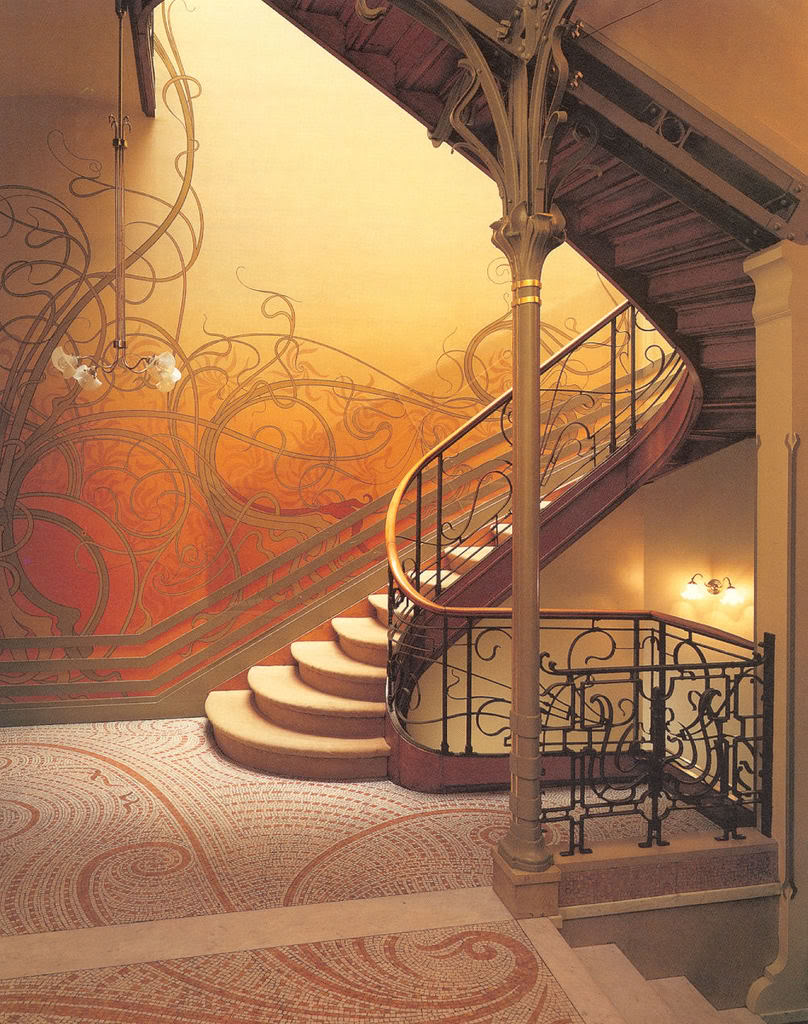

In any case, its formal beginning came in the 1890s with Art Nouveau — literally meaning "New Art" — which attempted to create an entirely new architectural (and artistic) style.

This was a conscious departure from the historically-inspired architecture of the 19th century.

This was a conscious departure from the historically-inspired architecture of the 19th century.

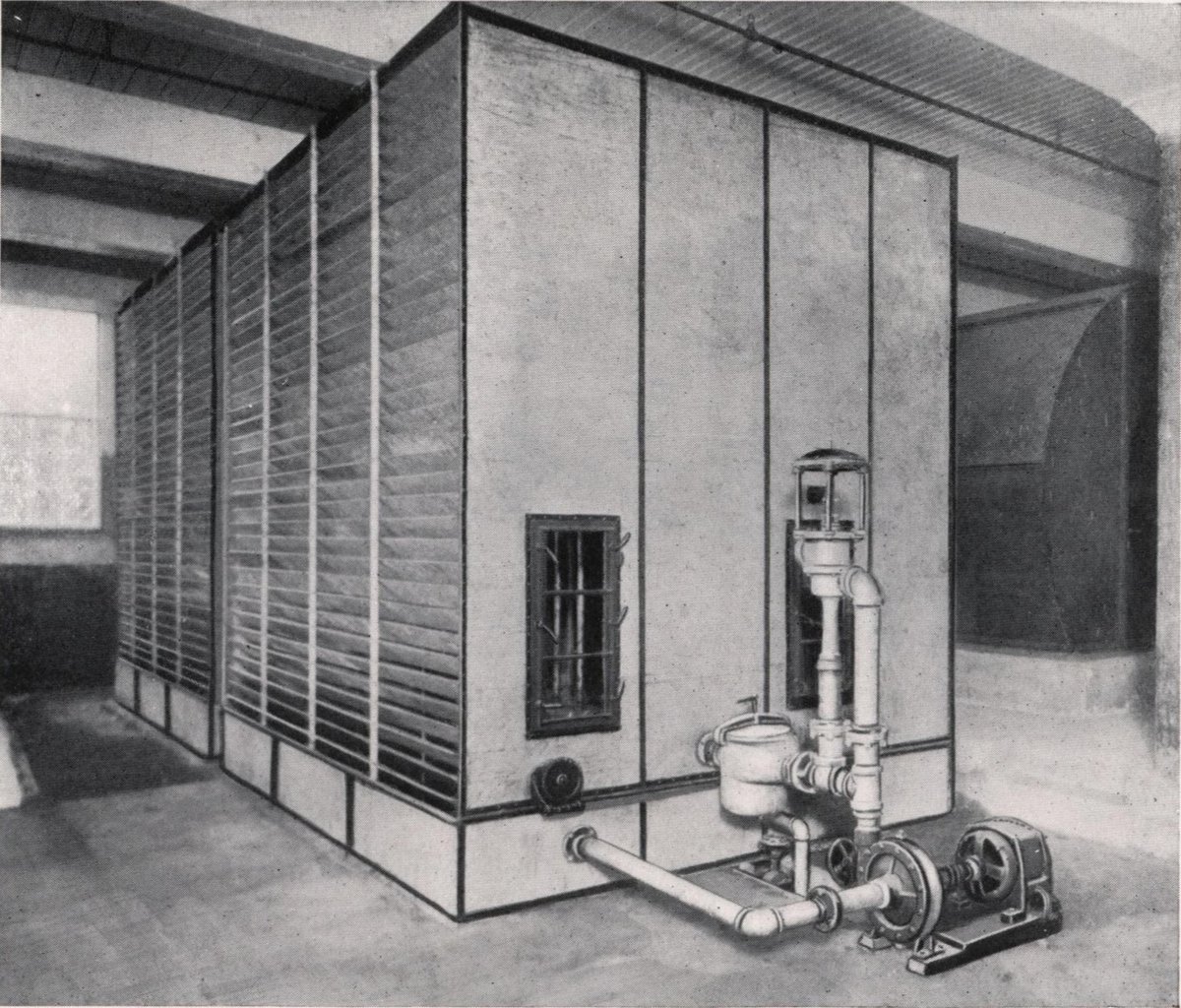

Art Nouveau gave way to Art Deco, which in turn was overtaken by a style that had been formulating in Germany and Austria since the early 1900s among architects like Adolf Loos, Le Corbusier, Mies, and the Bauhaus School.

This came to be known as the "International Style".

This came to be known as the "International Style".

But this wasn't only a difference of outward appearance — i.e. of ornamentation or shape.

It also represented a fundamental shift in *how* buildings were made; inventions like reinforced concrete, plate glass, and power tools totally changed what was possible...

It also represented a fundamental shift in *how* buildings were made; inventions like reinforced concrete, plate glass, and power tools totally changed what was possible...

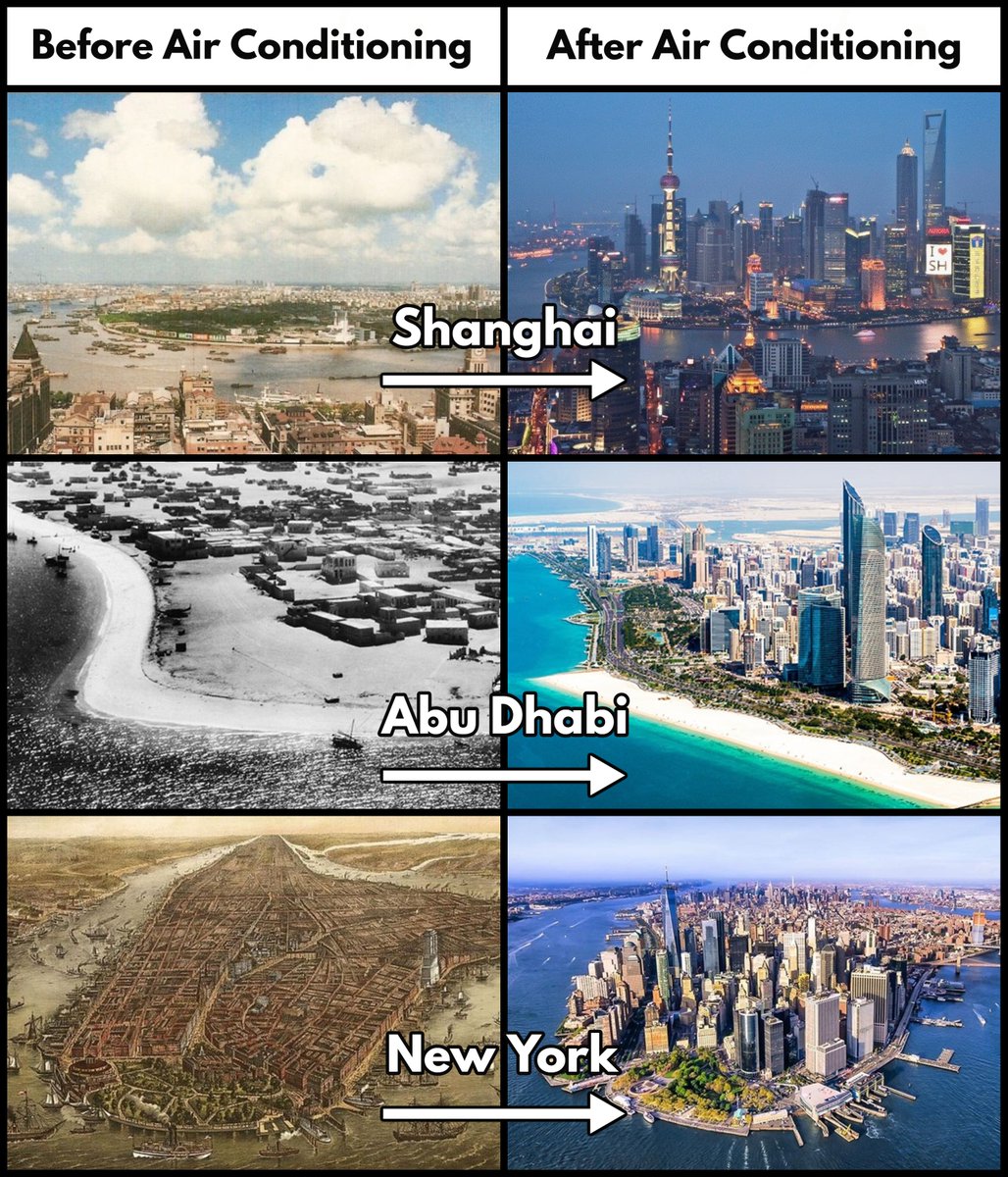

The International Style rose to prominence in the decades after the Second World War during an uprecedented global construction boom.

It was quicker and cheaper; suddenly everybody, everywhere was building in more or less the same way.

Historical styles were no more.

It was quicker and cheaper; suddenly everybody, everywhere was building in more or less the same way.

Historical styles were no more.

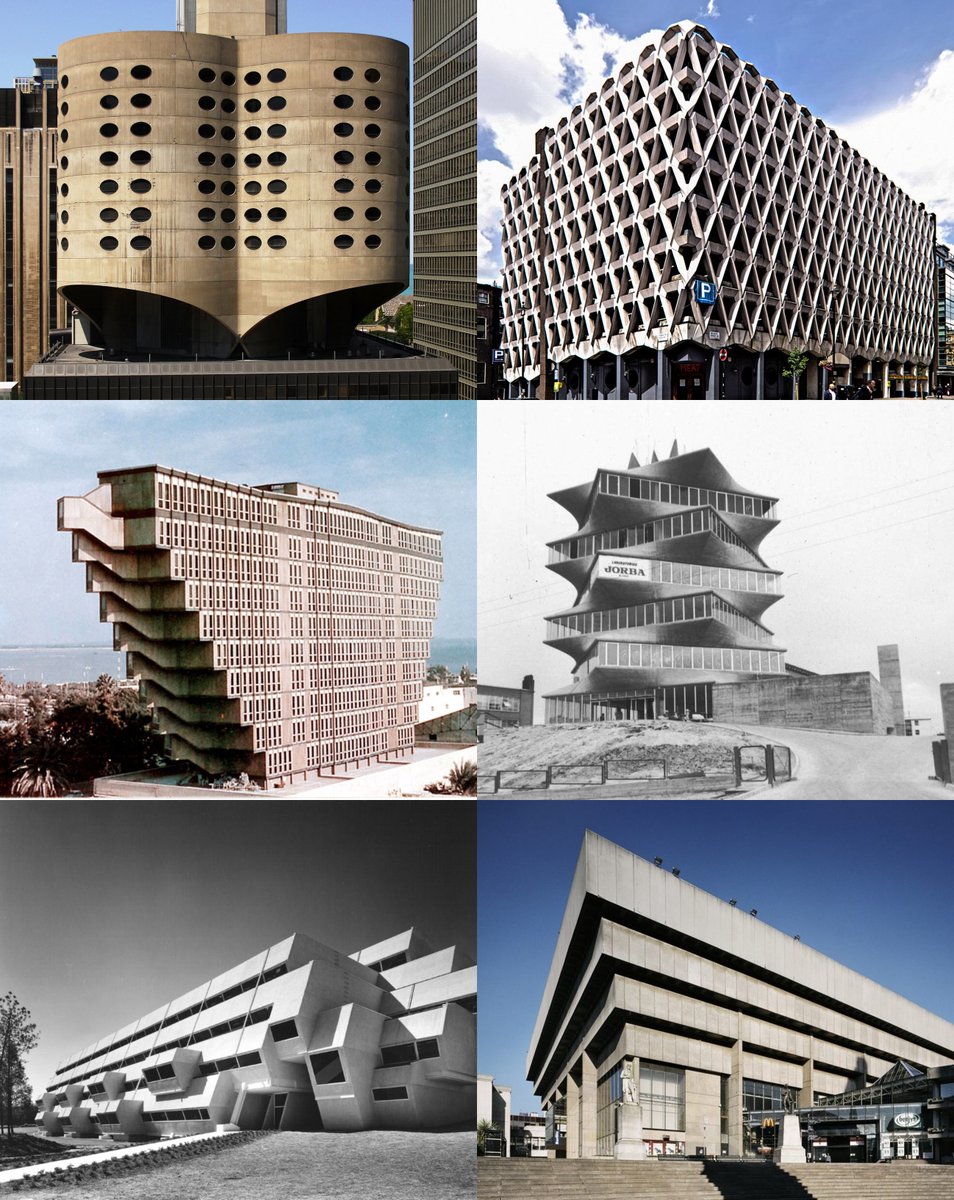

Since then the International Style has splintered into or been replaced by everything from Brutalism (pictured below) and Postmodernism to Deconstructivism and Biomimetic Architecture.

All of which are usually bundled together under the name of Modern Architecture.

All of which are usually bundled together under the name of Modern Architecture.

Has Modern Architecture been unfairly criticised?

It is often framed as if the sterile, boring, cheap, and ugly tower blocks and high rises of the 21st century have replaced beautiful Baroque palaces and Gothic cathedrals, but that isn't quite right.

It is often framed as if the sterile, boring, cheap, and ugly tower blocks and high rises of the 21st century have replaced beautiful Baroque palaces and Gothic cathedrals, but that isn't quite right.

Since 1900 the world's population has risen from under 2 billion to nearly 8 billion — where were all these people supposed to live and work?

Modern Architecture offered the quickest and cheapest solution; it didn't "replace" historic architecture so much as overwhelm it.

Modern Architecture offered the quickest and cheapest solution; it didn't "replace" historic architecture so much as overwhelm it.

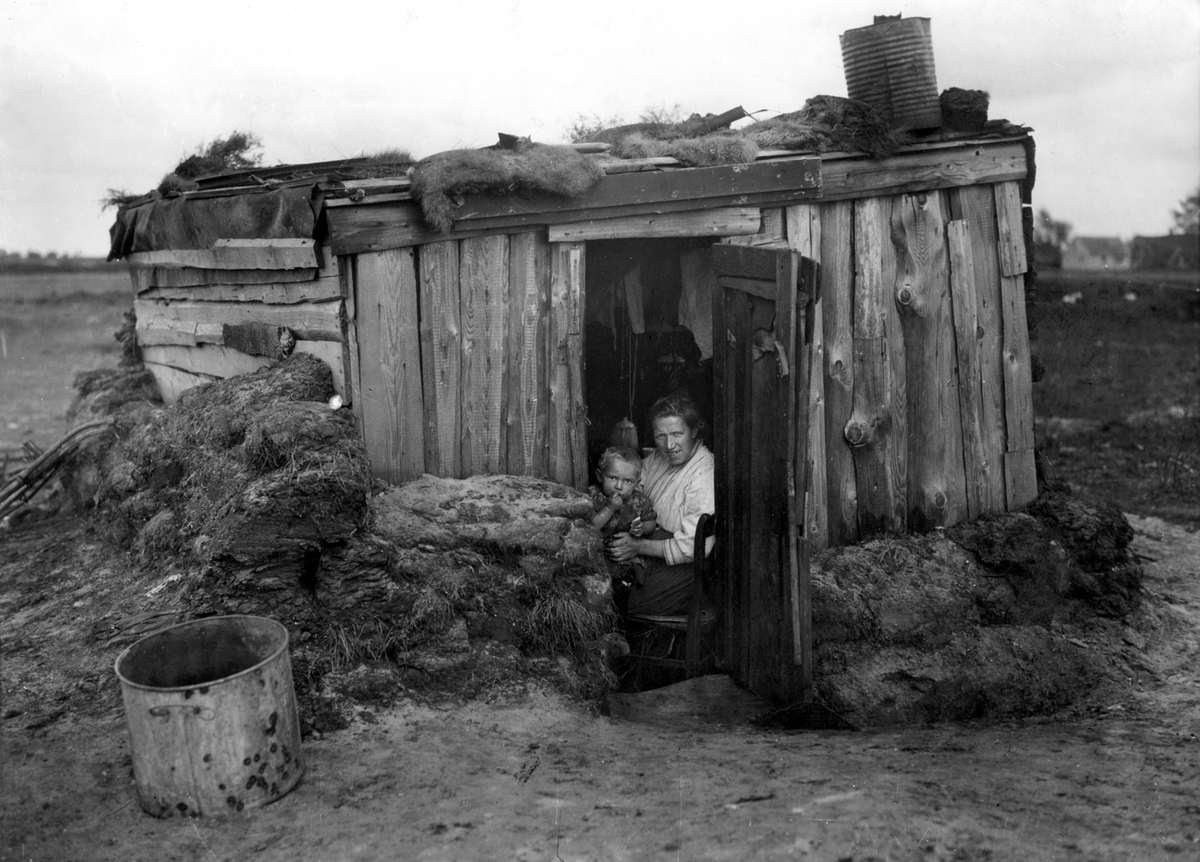

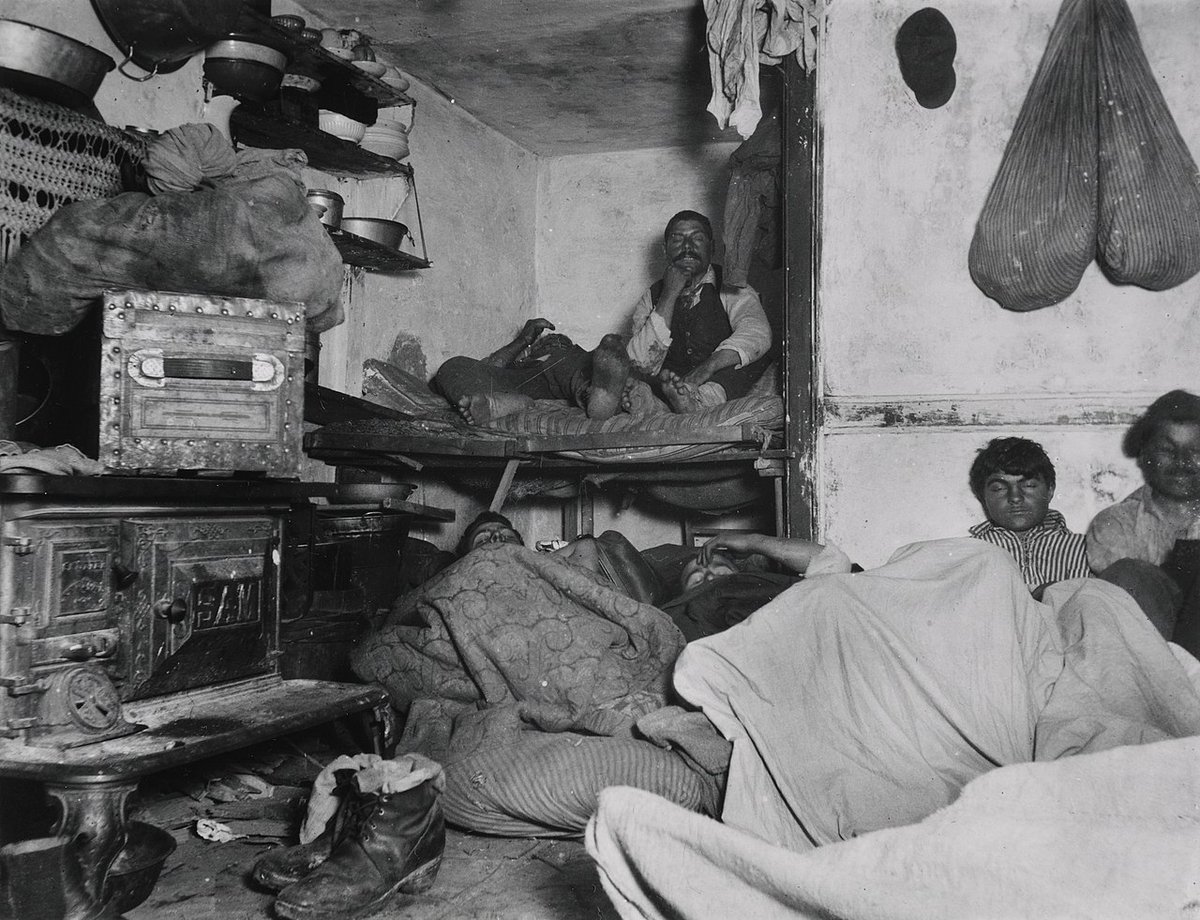

And what Modern Architecture has directly replaced is the destitution of the past.

We now have boring and ugly — but habitable — tower blocks instead of filthy tenements and squalid huts.

In which case, despite its many flaws, Modern Architecture has surely been successful.

We now have boring and ugly — but habitable — tower blocks instead of filthy tenements and squalid huts.

In which case, despite its many flaws, Modern Architecture has surely been successful.

But even if Modern Architecture was a solution to the problem of how we could build effectively, cheaply, and quickly on a large scale, it doesn't explain why we essentially no longer build in historical styles at all.

The world is filled with examples waiting to be emulated...

The world is filled with examples waiting to be emulated...

And polls and studies show that the public overwhelmingly prefer what is usually but somewhat unhelpfully called "traditional architecture".

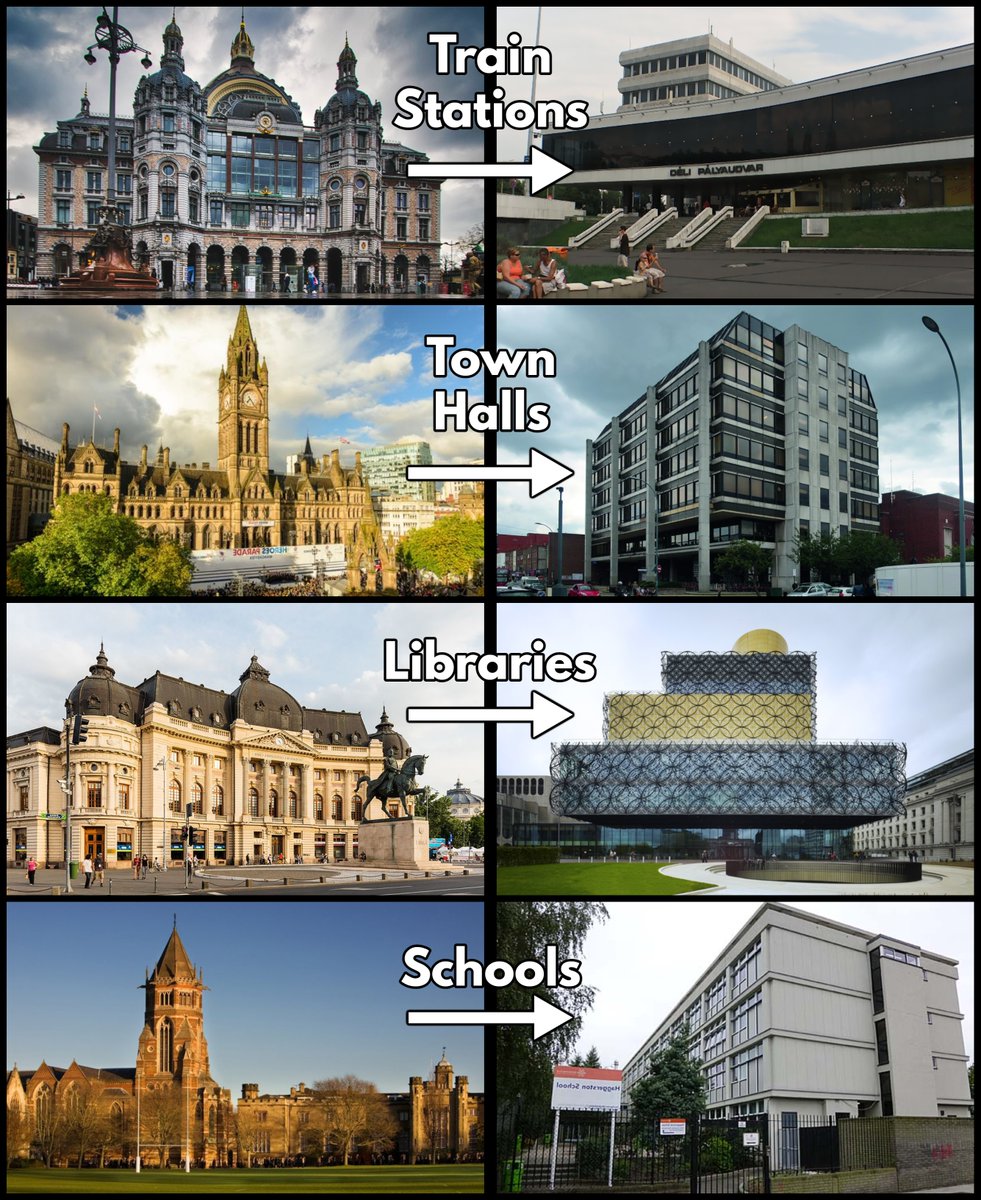

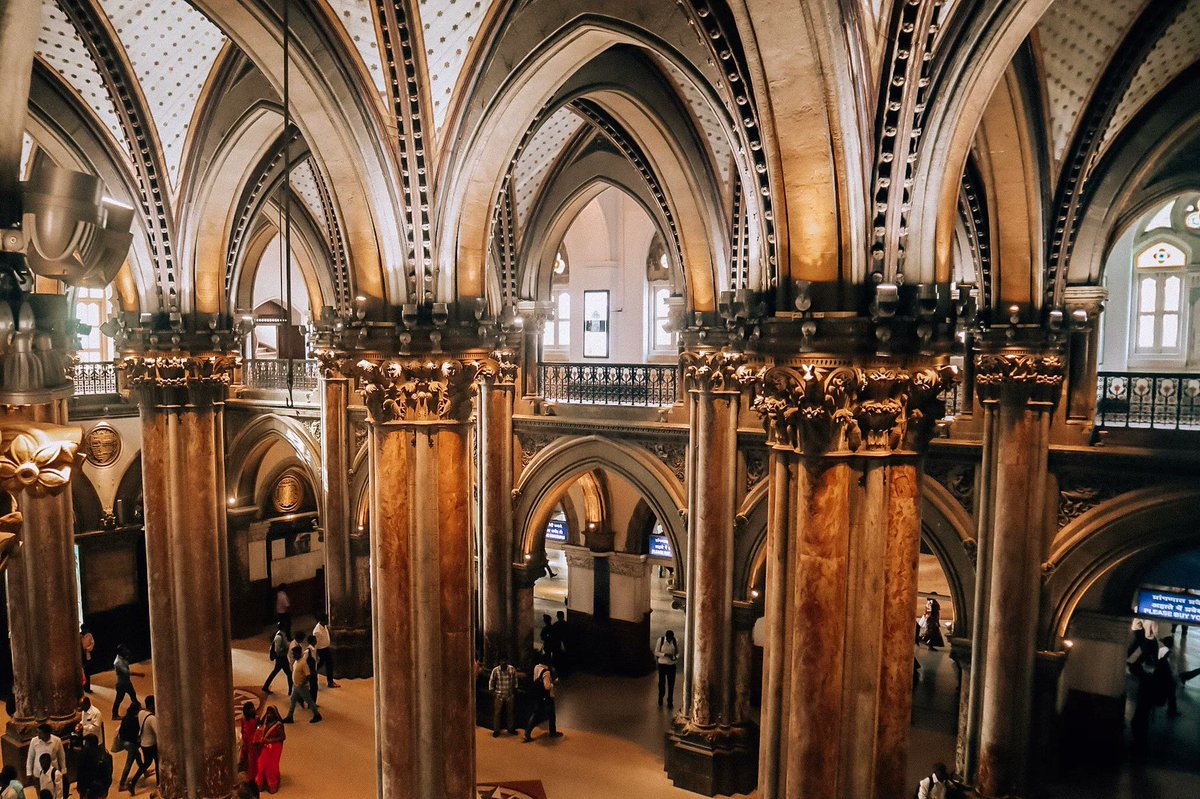

That isn't surprising if we look at how train stations, schools, libraries, and town halls used to be built.

That isn't surprising if we look at how train stations, schools, libraries, and town halls used to be built.

Most frustrating about this is that, by virtue of the very technologies and materials that made Modern Architecture possible, we are also better placed to build historical architecture efficiently and quickly.

Everything you see here has been built in the last thirty years:

Everything you see here has been built in the last thirty years:

That was the historical centre of Dresden, ruined during the Second World War and recently rebuilt.

Beyond rebuilding there are places like the Neo-Byzantine Saint Sava Cathedral in Serbia or the People's Salvation Cathedral in Romania, both currently under construction.

Beyond rebuilding there are places like the Neo-Byzantine Saint Sava Cathedral in Serbia or the People's Salvation Cathedral in Romania, both currently under construction.

Not to mention something like Nashville's Schermerhorn Symphony Center, which was built between 2003 and 2006.

Regardless of whether we should or shouldn't do so, these examples are clear proof that building in historical styles is still possible — if only we choose to do so.

Regardless of whether we should or shouldn't do so, these examples are clear proof that building in historical styles is still possible — if only we choose to do so.

Modern Architecture has had its triumphs: the Church of Hallgrímur, the Sydney Opera House, Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall, Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim, and so on.

But the public have made clear they want at least some historical architecture — will they ever get it?

But the public have made clear they want at least some historical architecture — will they ever get it?

Alas, to come full circle, perhaps it is simply inevitable that modern architecture — in the sense of being new — will be unpopular.

And that, when enough time has passed and Age has worked its magic, future generations will come to admire and even find it beautiful... or not?

And that, when enough time has passed and Age has worked its magic, future generations will come to admire and even find it beautiful... or not?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter