Large language models have demonstrated a surprising range of skills and behaviors. How can we trace their source? In our new paper, we use influence functions to find training examples that contribute to a given model output.

Influence functions are a classic technique from statistics. They are formulated as a counterfactual: if a copy of a given training sequence were added to the dataset, how would that change the trained parameters (and, by extension, the model’s outputs)?

Directly evaluating this counterfactual by re-training the model would be prohibitively expensive, so we’ve developed efficient algorithms that let us approximate influence functions for LLMs with up to 52 billion parameters: arxiv.org/abs/2308.03296

Identifying the most influential training sequences revealed that generalization patterns become much more sophisticated and abstract with scale. For example, here are the most influential sequences for 810 million and 52 billion parameter models for a math word problem:

Here is another example of increasing abstraction with scale, where an AI Assistant reasoned through an AI alignment question. The top influential sequence for the 810M model shares a short phrase with the query, while the one for the 52B model is more thematically related.

Another striking example occurs in cross-lingual influence. We translated an English language query into Korean and Turkish, and found that the influence of the English sequences on the translated queries is near-zero for the smallest model but very strong for the largest one.

Influence functions can also help understand role-playing behavior. Here are examples where an AI Assistant role-played misaligned AIs. Top influential sequences come largely from science fiction and AI safety articles, suggesting imitation (but at an abstract level).

The influence distributions are heavy-tailed, with the tail approximately following a power law. Most influence is concentrated in a small fraction of training sequences. Still, the influences are diffuse, with any particular sequence only slightly influencing the final outputs.

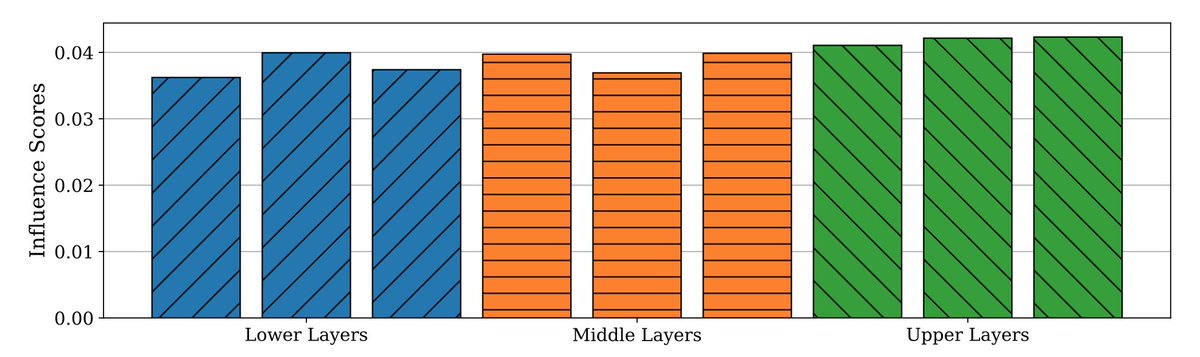

Influence can also be attributed to particular training tokens and network layers. On average, the influence is equally distributed over all layers (so the common heuristic of computing influence only over the output layer is likely to miss important generalization patterns).

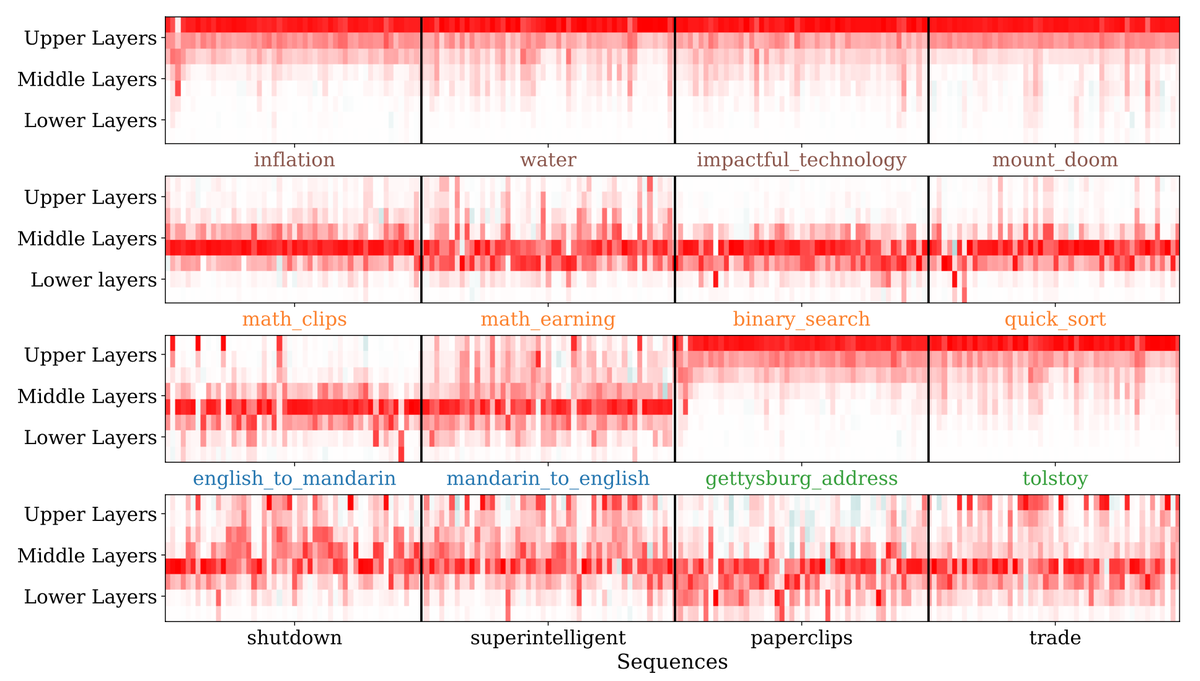

On the other hand, individual influence queries show distinct influence patterns. The bottom and top layers seem to focus on fine-grained wording while middle layers reflect higher-level semantic information. (Here, rows correspond to layers and columns correspond to sequences.)

This work is just the beginning. We hope to analyze the interactions between pretraining and finetuning, and combine influence functions with mechanistic interpretability to reverse engineer the associated circuits. You can read more on our blog: anthropic.com/index/influenc…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh