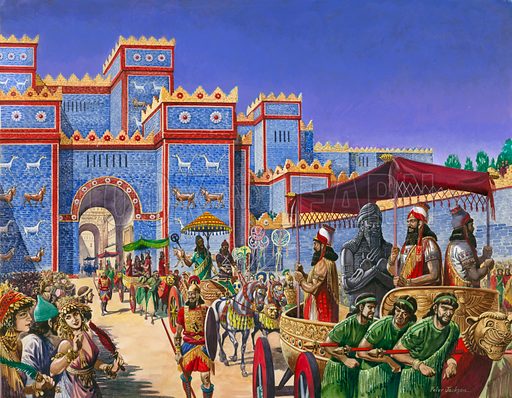

The Battle of Carchemish, the battle which secured the Neo-Babylonian Empire's hold on the Ancient Near East under Nebuchadnezzar II.

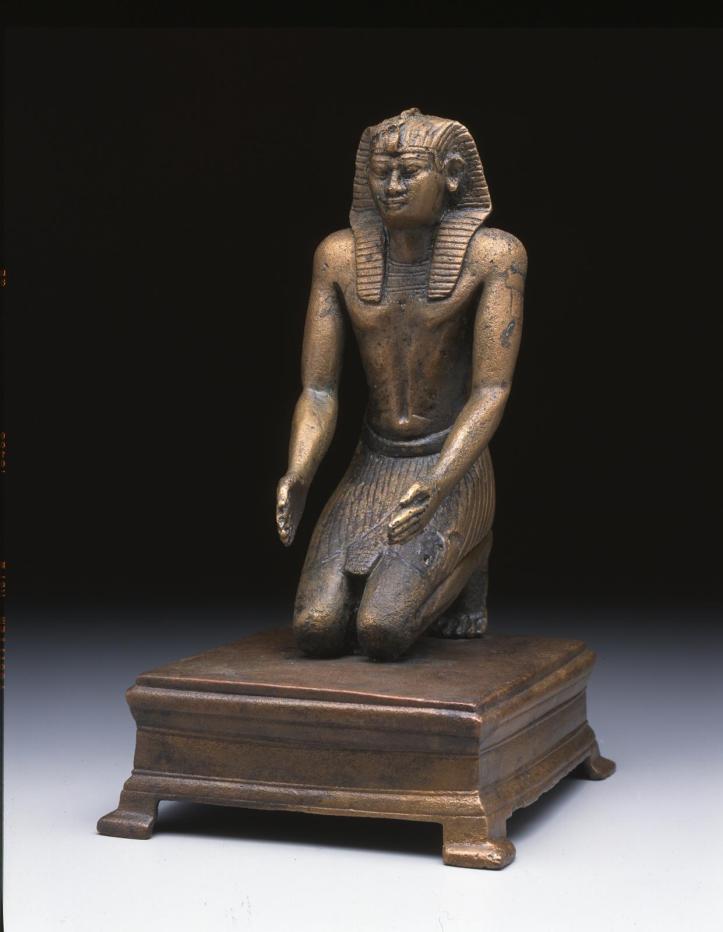

The Battle of Carchemish was fought in Carchemish on the Euphrates River about 605 BC between the armies of Egypt, led by Pharaoh Neco II, and Babylon, led by soon-to-be king Nebuchadnezzar.

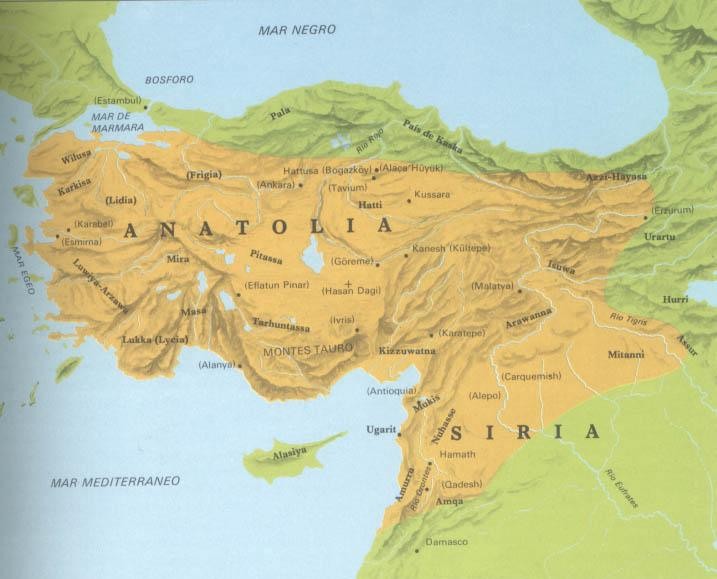

Carchemish was on the west bank of the Euphrates in what is now southern Turkey, along the Syrian border. It was located at a strategic crossing of the Euphrates used for trade between Syria, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia.

The Hittites lost control of the city to the “Sea Peoples” during the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

When the Assyrians rose to power several centuries later, they were forced to pay tribute to Assyrian kings Shalmaneser III and Tiglath-pileser IV during the second half of the 800s BC before finally being taken by Sargon II in 717 BC.

Carchemish was excavated by David G. Hogarth and later by Sir Leonard Woolley between 1911 and 1920.

In the decade before the battle, the Assyrians had been driven out of their capital, Nineveh, in 612BC by an allied army of Medes, Scythians, Babylonians, along with other minor allies.

The Assyrians were forced out of their second capital, Haran, in 609BC and fled to Carchemish, which was under Egyptian rule under Pharaoh Neco II.

Pharaoh Neco had already tried to conquer Assyria’s western provinces while Babylon was conquering Assyria from the east.

Neco was ambitious. Herodotus records (4.42) that Neco sent out an expedition of Phoenicians that spent three years sailing from the Red Sea around Africa to the Strait of Gibraltar and back to Egypt.

Josephus (Antiquities 10.5.1) said that Neco’s support of Assyria stemmed from his desire to take advantage of the power vacuum left after the defeat of the Assyrian empire.

Neco allied with the remnants of Assyria its king Ashuruballit II but planned to assume control of the western half of the ANE upon his victory.

Neco was held up on his way to the battle by King Josiah of Judah. Neco defeated Josiah at the Battle of Megiddo, which is recorded in the Bible in 2 Kings 23:29-30 and 2 Chronicles 35:20-23.

The Chronicler (2 Chron. 35:21) records Neco claiming that God had commanded him to make haste to Carchemish and that God was with him.

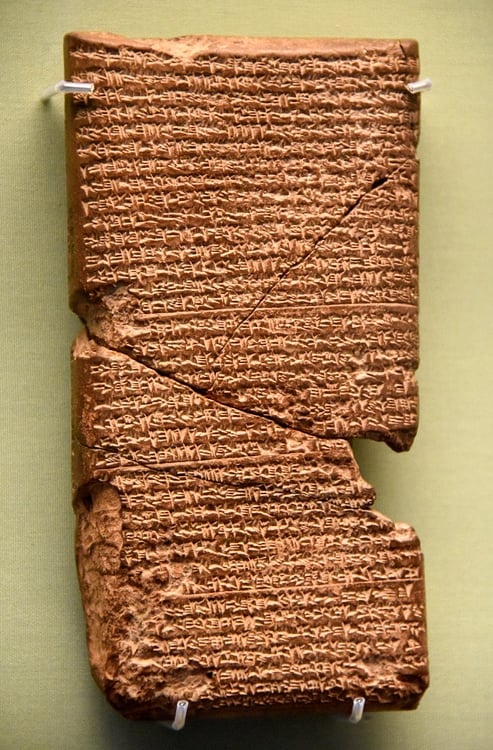

The Babylonian Chronicle is our best source for the battle. It is also called the Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle or the Jerusalem Chronicle, because it also details the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586BC.

The Babylonian Chronicle records that Babylonian king Nabopolassar while his eldest son, crown prince Nebuchadnezzar took command of the army marched toward Carchemish.

“He accomplished their defeat and beat them to non-existence. As for the rest of the Egyptian army which had escaped from the defeat so quickly that no weapon had reached them…”

“…in the district of Hamath the Babylonian troops overtook and defeated them so that not a single man escaped to his own country.”

Nabopolassar died and Nebuchadnezzar assumed the throne. The next year he returned to the region and collected tribute, defeated Ashkelon, and secured his holdings almost to the border of Egypt.

Ashkelon repeatedly begged Egypt for help against Nebuchadnezzar, but Neco refused to respond. He just barely was able to repel a Babylonian attack against his eastern border in 601.

Neco died in 595BC never having recovered any of the land lost to Nebuchadnezzar.

Nebuchadnezzar went on to turn Babylon (the Neo-Babylonian Empire) into the largest and most powerful empire of the ANE.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter