On 28 April 1986, in the Ashoka Hall of Rashtrapati Bhavan, the 87-year-old General Kodandera Madappa Cariappa was invested with the rank of Field Marshal and presented the baton of office by President Giani Zail Singh.

The book titled Field Marshal K.M. Cariappa written by his son, Air Marshal K.C. Cariappa (Retd), gives a detailed account of the event. He writes:

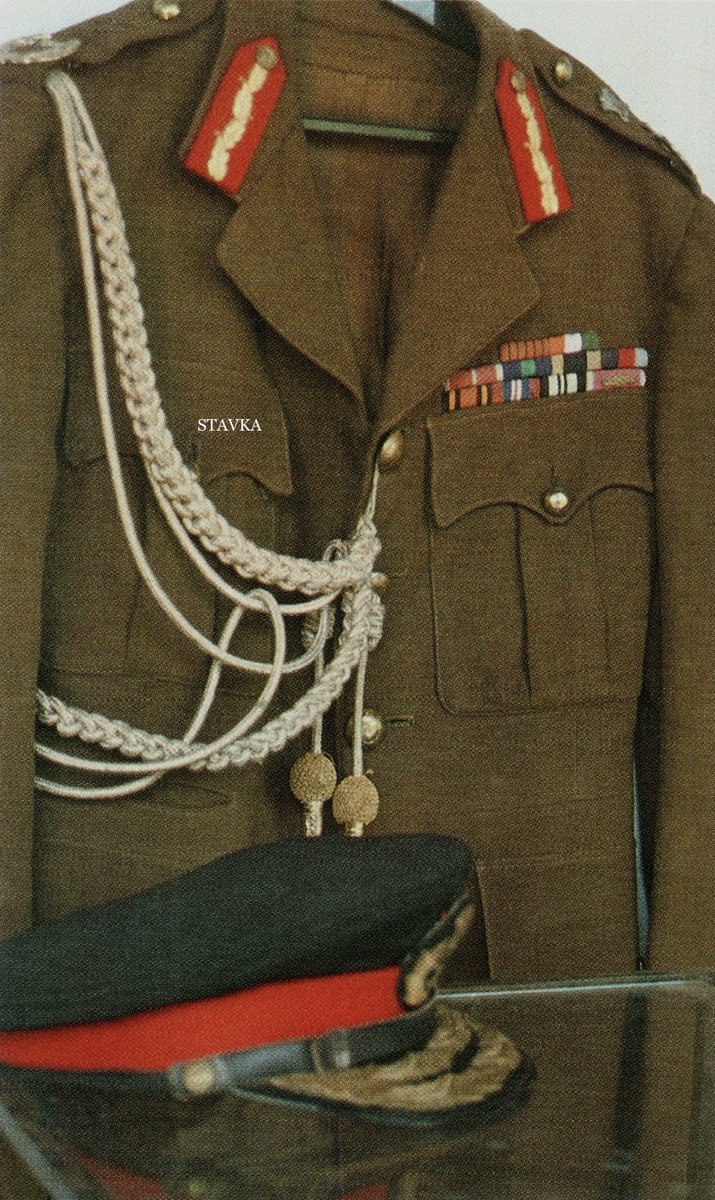

“It was a particularly memorable event for us in the family. His two surviving brothers Nanjappa and Bopaiah had arrived from Kodagu to be present at the Investiture Ceremony. The Ashoka Hall was filled to capacity by the high and the mighty of the land. Father was in his dress uniform, something he had not worn for many, many years. He wore, as always, narrow pointed shoes.+

The book titled Field Marshal K.M. Cariappa written by his son, Air Marshal K.C. Cariappa (Retd), gives a detailed account of the event. He writes:

“It was a particularly memorable event for us in the family. His two surviving brothers Nanjappa and Bopaiah had arrived from Kodagu to be present at the Investiture Ceremony. The Ashoka Hall was filled to capacity by the high and the mighty of the land. Father was in his dress uniform, something he had not worn for many, many years. He wore, as always, narrow pointed shoes.+

At that time he was being treated for a particularly painful toe on his right foot. In fact at home he would always wear a shoe on the left foot, but allowed himself to wear a slipper on the right. He would often be in excruciating pain, but always maintained a stiff upper lip. For the investiture he would not hear of not wearing a shoe on his swollen foot.+

He arrived at Rashtrapati Bhavan where he was received with due ceremony, and ushered to the special chair where he was to sit alone till after the investiture. He refused to use a walking stick though he limped heavily, nor did he accept the arm proffered by an ADC. The arrival of the President was heralded by the traditional fanfare when we all stood up; the National Anthem followed.+

The Defence Secretary, SK Bhatnagar then announced the commencement of the ceremony and proceeded to read the Gazette notification informing of the Government's decision. It was a process that took about ten minutes, but one during which Father had to stand. He stood as steadily as he could, perhaps swaying imperceptibly.

I wondered how he was bearing up with the agony he must have been experiencing. After the citation was read Father walked up to the President who presented him with the Field Marshal's baton-the insignia of rank.+

I wondered how he was bearing up with the agony he must have been experiencing. After the citation was read Father walked up to the President who presented him with the Field Marshal's baton-the insignia of rank.+

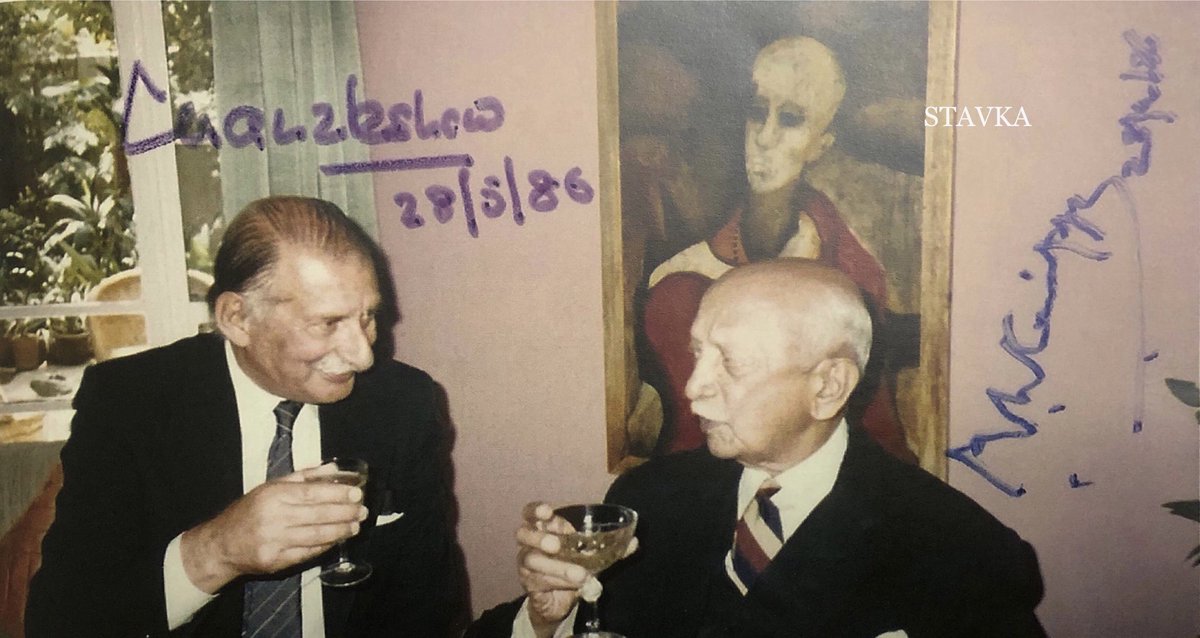

And it was all over. Well, almost. There was no question of Father being able to sit down immediately after that. He was surrounded by many of those present who wished to shake his hand and congratulate him after which tea was served. The President stayed on to be with Father as did such dignitaries as the Prime Minister, members of the Cabinet, Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw and the Service Chiefs who were present. Photographers clicked away feverishly not wanting to miss the historic photo opportunity.+

He continued standing till it was time for him to leave. It was a particularly touching moment to see a soldier, my father, receiving the ultimate honour of his profession. I can still see him in my mind’s eye, standing as motionless as he possibly could in front of the President.+

The ceremony over, we trooped off to Nalini’s (Daughter) home where with the other Grand Old Man of the Indian Army, Field Marshal Manekshaw, a bottle of champagne was opened to celebrate the great event.”

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh