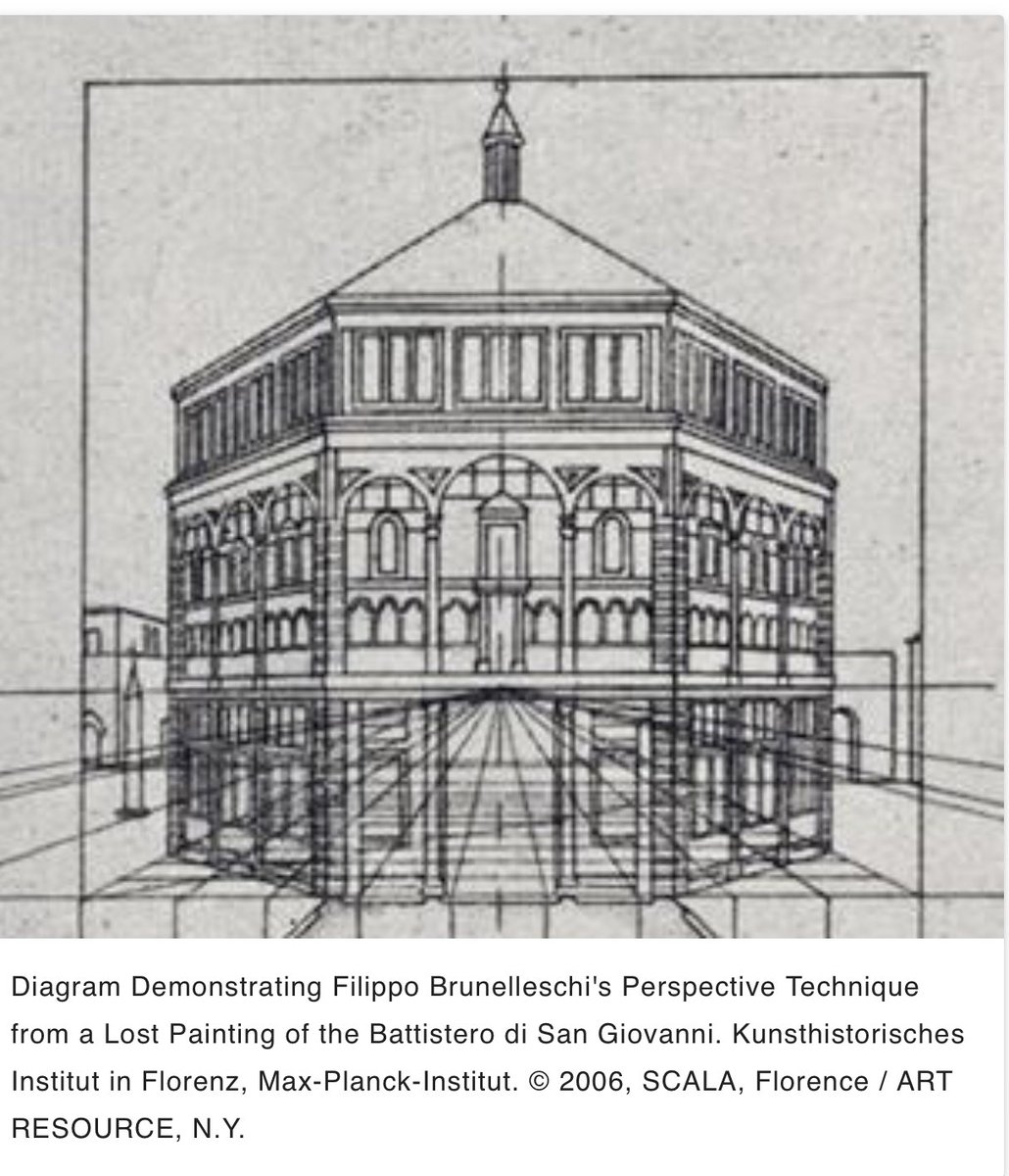

In Art, perspective is a technique used to represent three-dimensional objects and depth on a two-dimensional surface.

Italian architect and engineer, Filippo Brunelleschi, is credited with formalizing the mathematical principles of linear perspective in the early 15th century.

Italian architect and engineer, Filippo Brunelleschi, is credited with formalizing the mathematical principles of linear perspective in the early 15th century.

Masaccio was the first Renaissance painter to incorporate Brunelleschi’s discovery into art. This is seen in Masaccio’s Holy Trinity (1427) in the church of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. In the perspective diagram overlaying Masaccio’s painting: Masaccio painted from a low vantage point, as if viewers are looking up at the Christ figure, we see the orthogonals (diagonal lines that converge in a single point, in red) in the ceiling coffers. By tracing all the red lines, we see that the vanishing point, or point of convergence, is on the ledge upon which two church donors kneel.

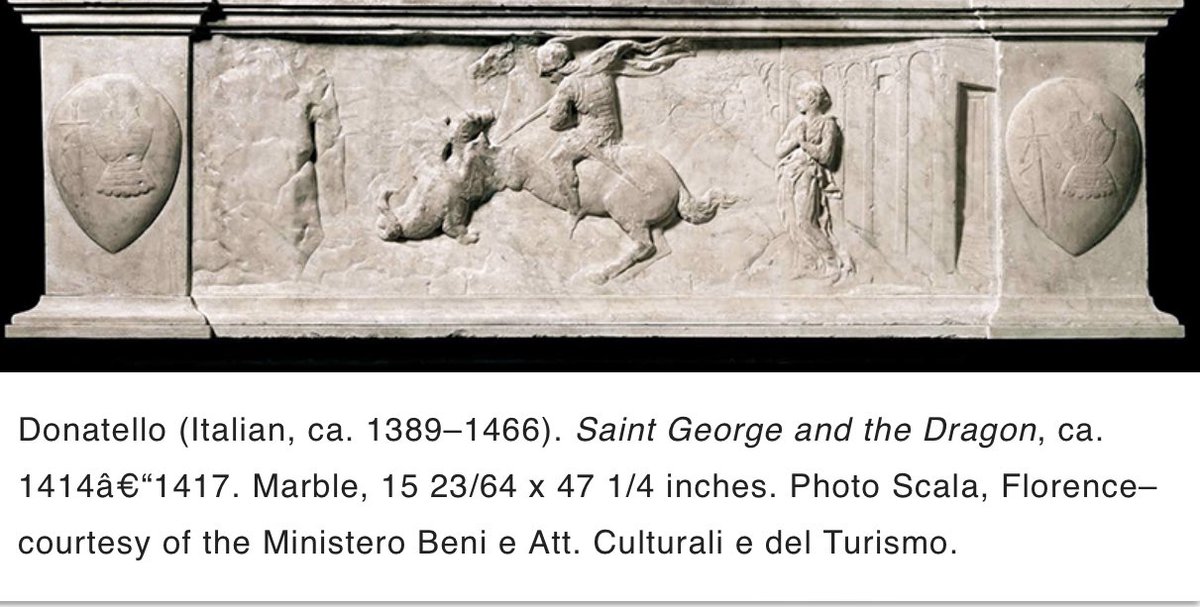

Donatello’s “St. George and the Dragon” is a relief sculpture that depicts the Christian legend of St. George slaying a dragon to save a princess. Donatello employs perspective using various techniques:

1. The characters and elements are carved in varying degrees of high relief, which adds a sense of depth and three-dimensionality to the work.

2. Accurate proportions are used to give a sense of space and depth. Depth is suggested through optical qualities in the carving, which emphasize light and shadow. Along with the illusion of space, this work produces an illusion of real figures.

1. The characters and elements are carved in varying degrees of high relief, which adds a sense of depth and three-dimensionality to the work.

2. Accurate proportions are used to give a sense of space and depth. Depth is suggested through optical qualities in the carving, which emphasize light and shadow. Along with the illusion of space, this work produces an illusion of real figures.

Ghiberti's artistic genius is reflected in his innovative use of perspective and his rendering of the three-dimensional form. He also considered the placement of a panel and planned the depth of carving accordingly, another of his innovations. Shallower reliefs appear in the bottom panels, with deeper reliefs at the top, adjustments that take into consideration the viewer's vantage point.

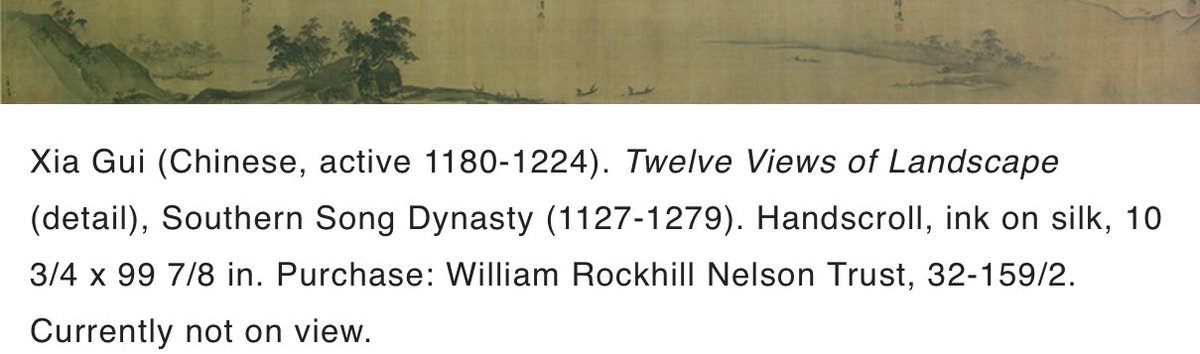

Chinese artists invented Atmospheric Perspective. This technique uses color and clarity to show distance. Objects farther away are lighter and less distinct, while nearer objects are darker and clearer.

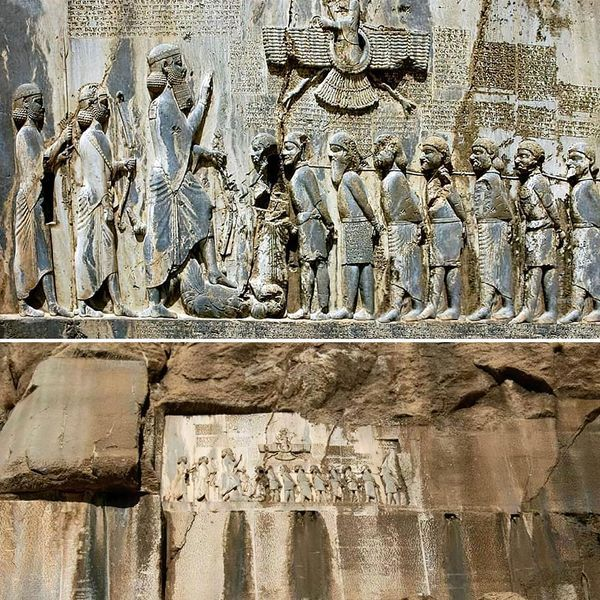

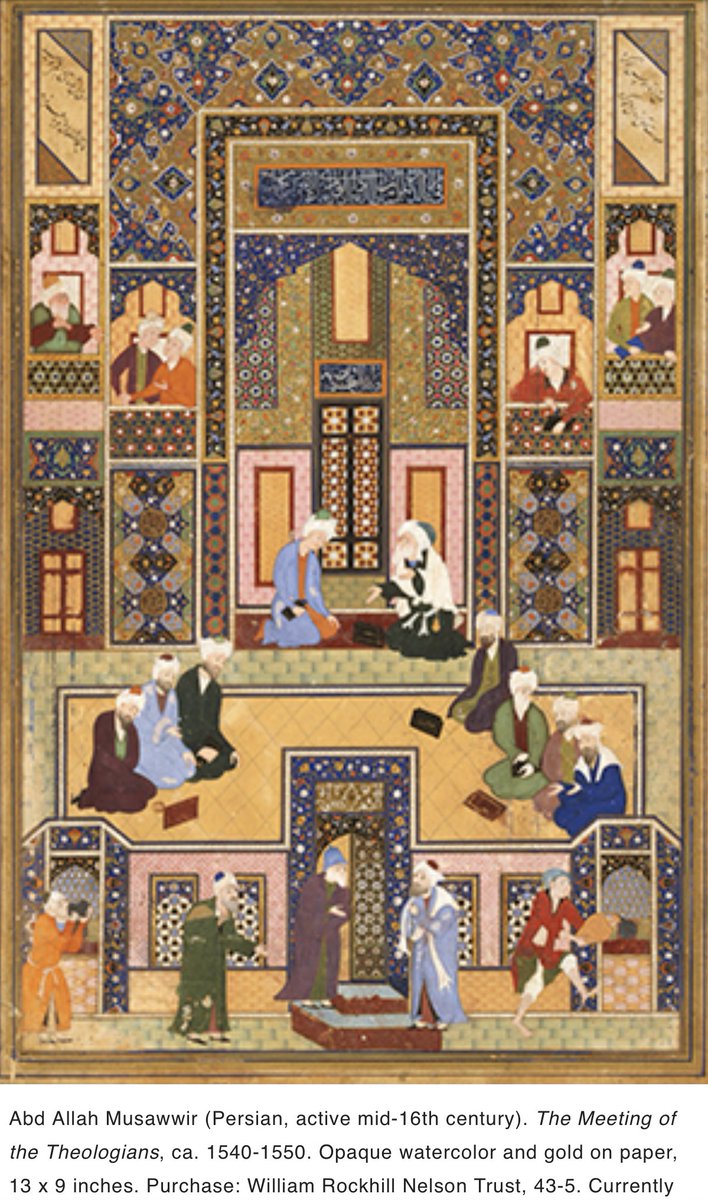

Persian artists were innovating perspective through the use of surface decoration to indicate depth. Abd Allah Musawwir used flattened compartments filled with dazzling patterns to suggest the receding interior of a religious school. The artist also illustrated groups of stylized figures in varying sizes, to denote their proximity to the viewer.

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh