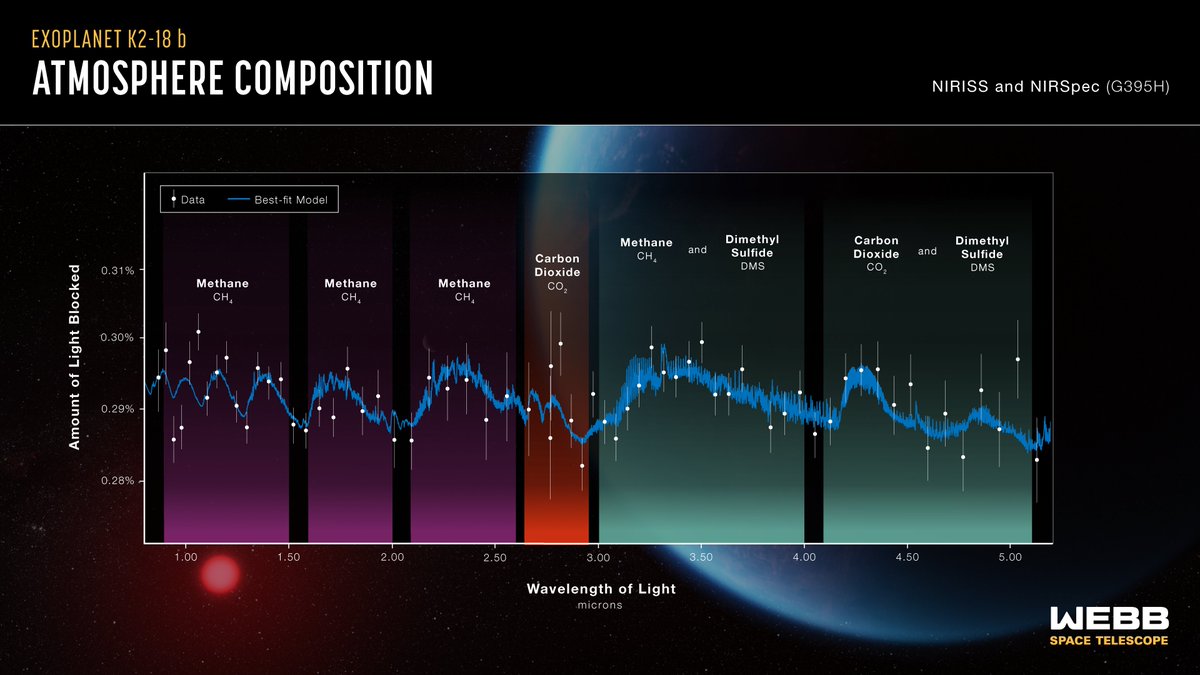

The Webb telescope has detected carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18 b, a potentially habitable world over 8 times bigger than Earth. Webb’s data suggests the planet might be covered in ocean, with a hydrogen-rich atmosphere: go.nasa.gov/3sGKNLe

Webb also hinted at a detection of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) on K2-18 b. On Earth, this molecule is only produced by microbial life. Because the detection needs to be confirmed, the team plans to follow up and look for additional evidence of biological activity on the planet.

While K2-18 b is in the habitable zone (where conditions are right for liquid water to exist), that does not necessarily mean it can support life. For instance, it may have a hostile environment due to its active star. Its ocean may also be too hot to be habitable.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter