The most decisive battle of the past 500 years was fought OTD in 1759, on a windswept Canadian plain by fewer than ten thousand men. It decided the fate of the Americas and shaped world events for centuries to come.

Thread on the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

Thread on the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

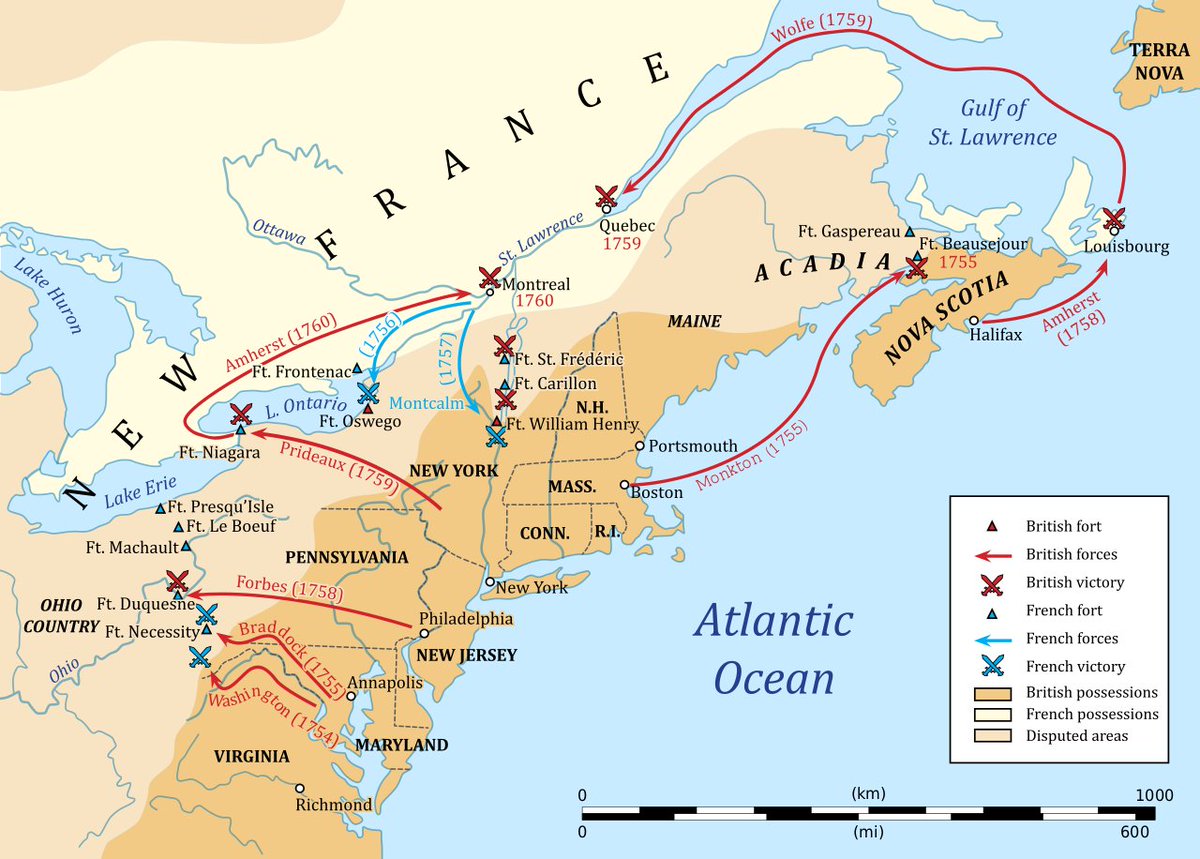

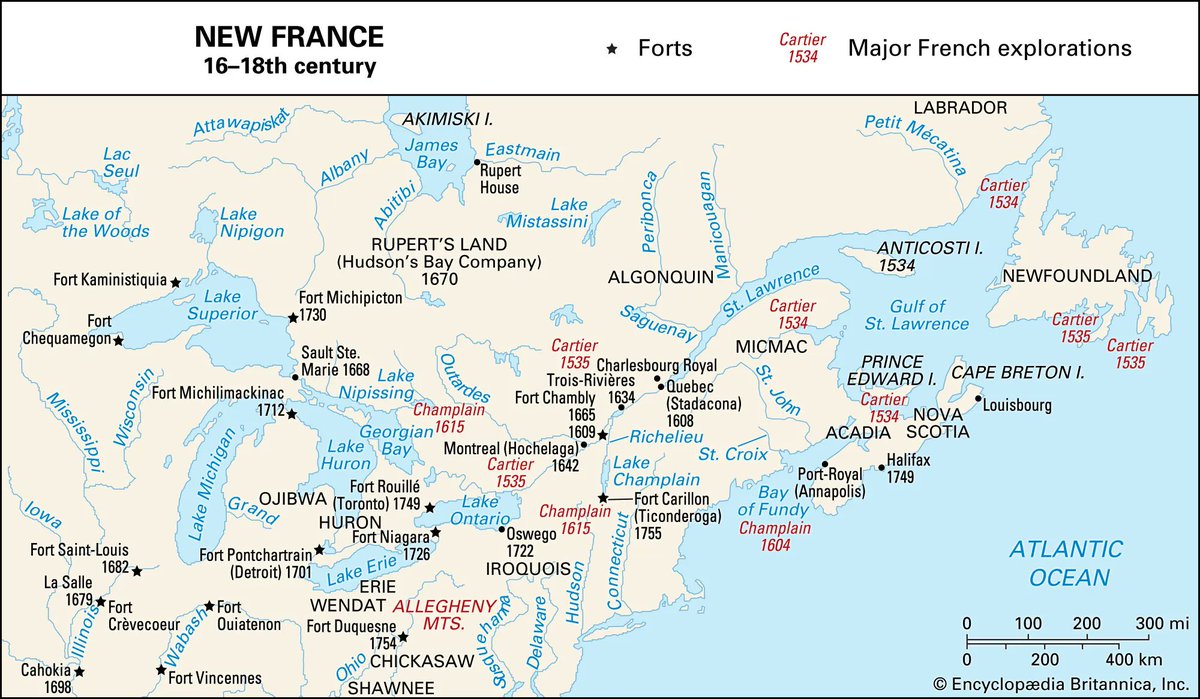

What became known as the Seven Years' War was formally declared by France and Britain in 1756, although fighting had broken out in the North American colonies two years earlier. British colonials began by pushing over the Appalachians to seize French forts, but were repulsed.

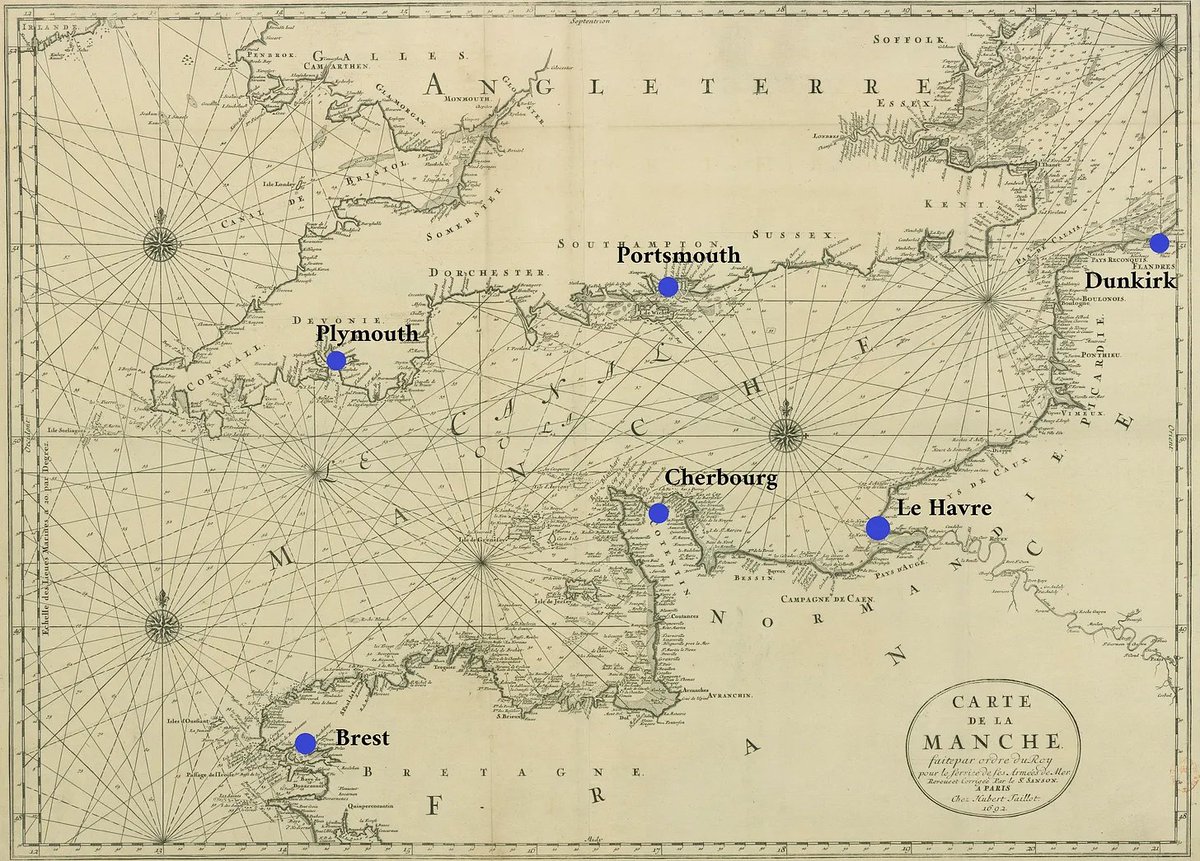

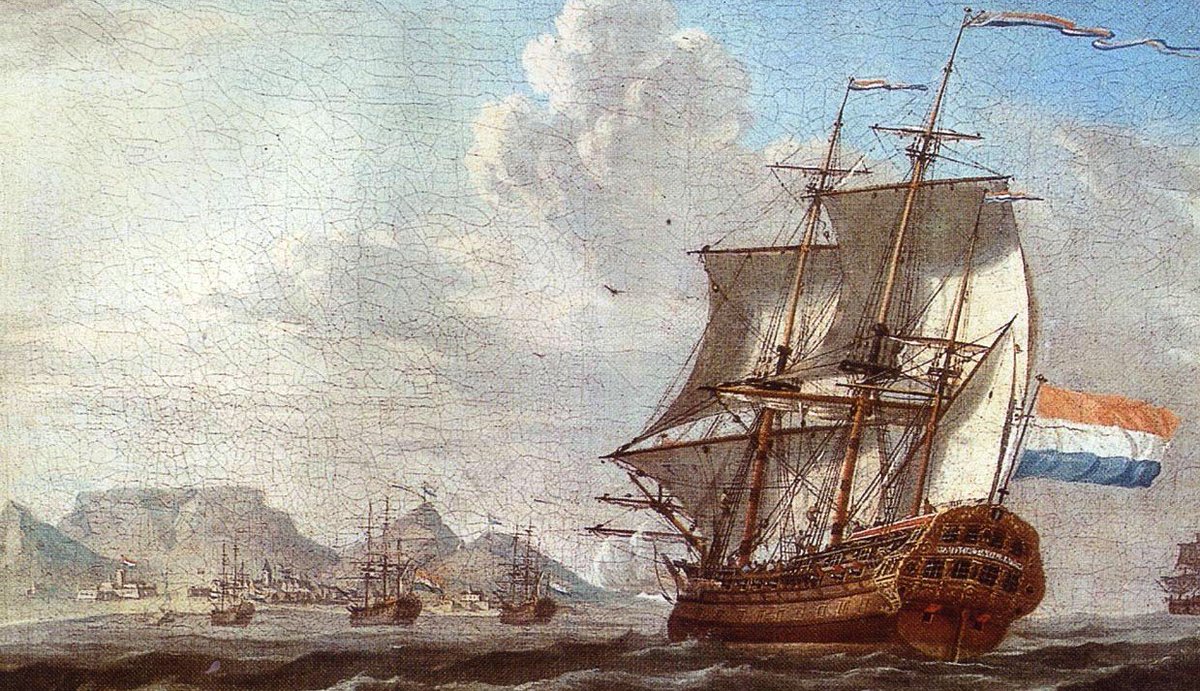

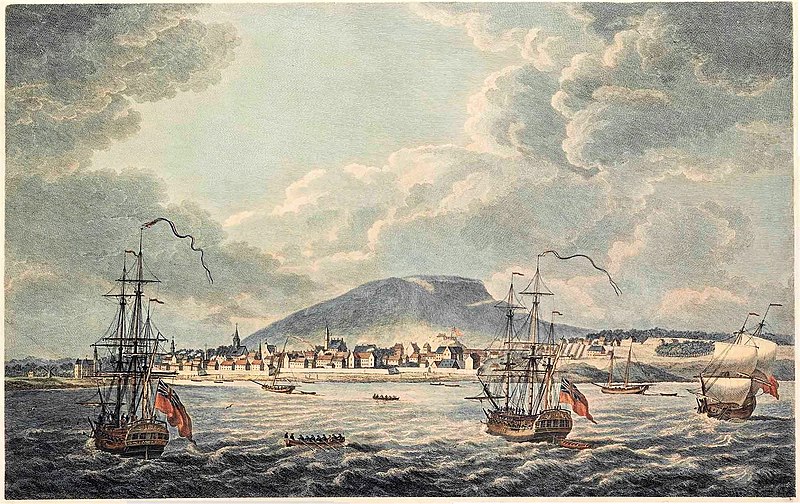

It was not until 1758 that the British saw any success, when they seized Louisbourg, a major fortress guarding the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and captured the upper Ohio valley. The ground was set for a pincer attack on the St. Lawrence, the heart of French Canada.

That attack came the following year. The Royal Navy landed an expedition just north of Quebec City, while a force of regulars and colonial militias stormed Ft. Niagara, cutting off the route from the St. Lawrence to the rest of New France.

Of the two, Quebec was more important. It controlled naval access to the entire territory, standing at a narrow point of the St. Lawrence surrounded by shoals, above where the river gradually starts to widen into the Gulf.

The conquest of Canada required Quebec.

The conquest of Canada required Quebec.

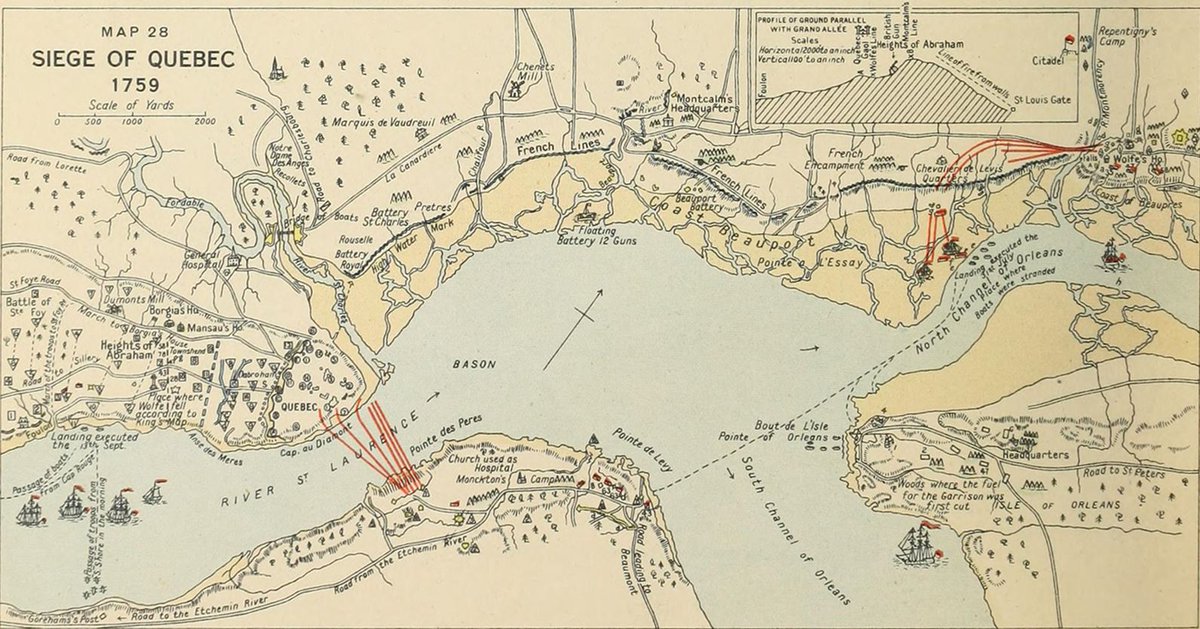

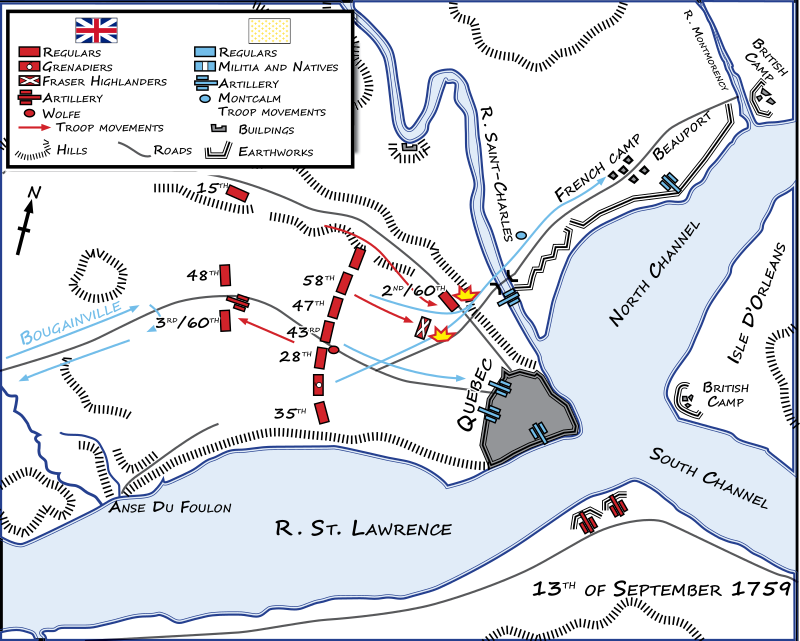

On 28 June, the British expedition under Major General James Wolfe landed the majority of its forces on the Île d'Orléans, then set up a battery opposite the city itself.

The French meanwhile entrenched in lines north of the city to prevent a British landing on the left bank.

The French meanwhile entrenched in lines north of the city to prevent a British landing on the left bank.

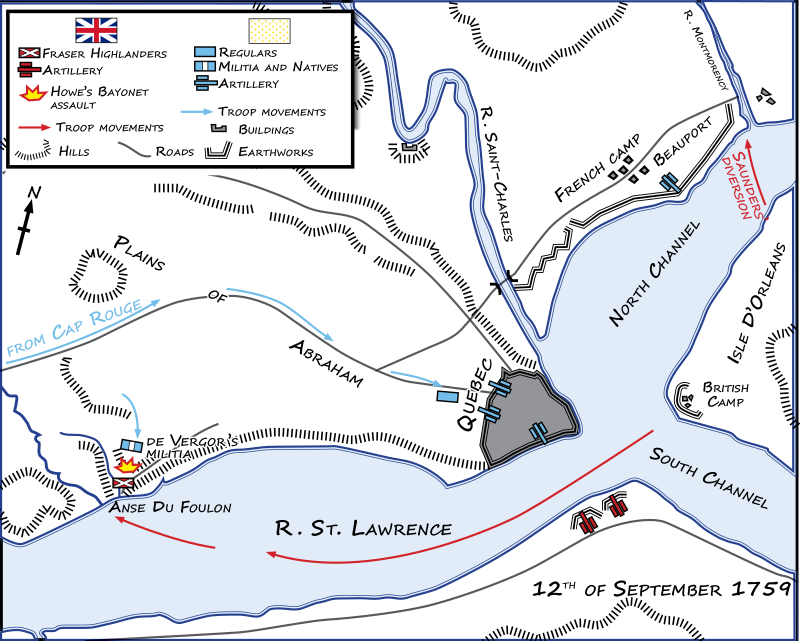

The siege lasted all summer. After a failed attempt to seize the left bank, Wolfe decided to take a gamble. On the night of 12 September he staged a naval diversion on the left bank, then sailed upriver with the bulk of his troops, over 4400, to land south of the city.

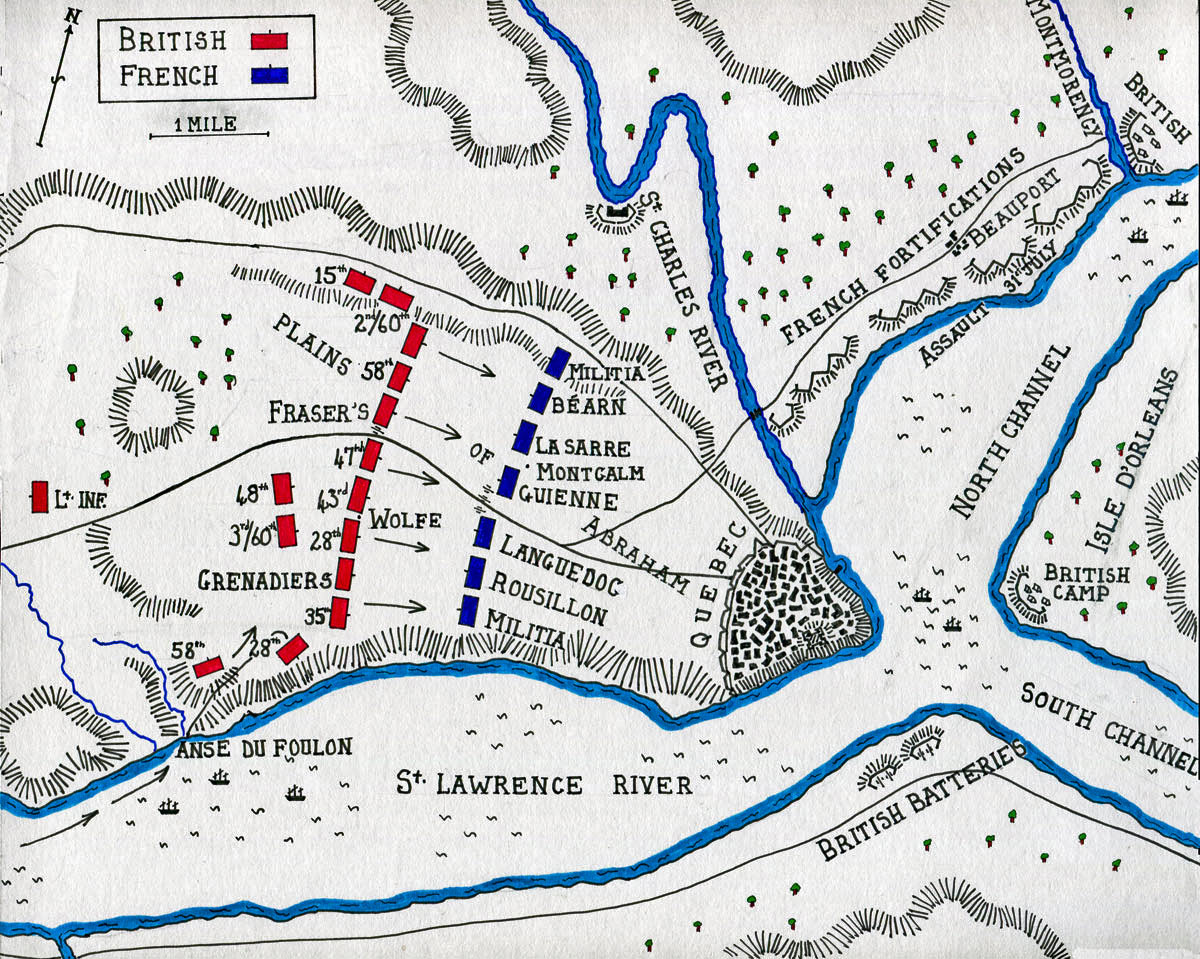

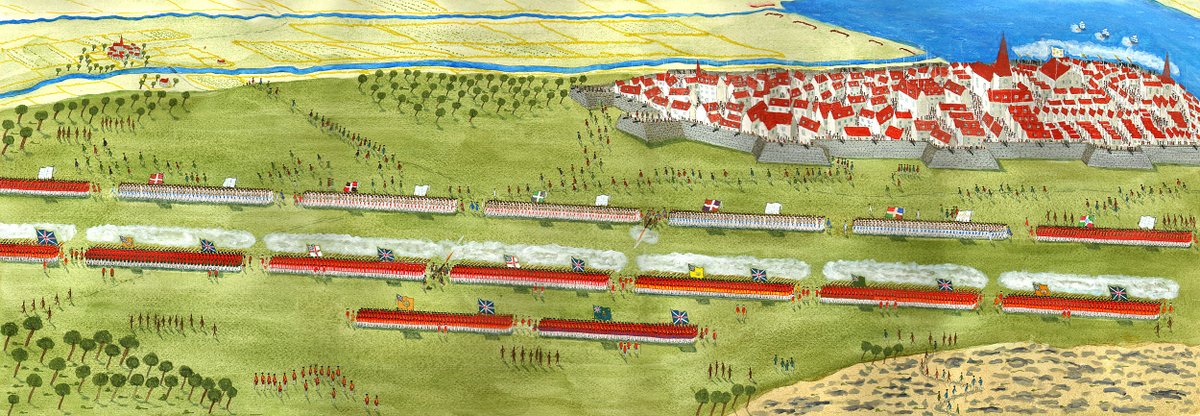

On the morning of the 13th, the French were stunned to see the British installed on the Plain of Abraham. Montcalm, the French commander, immediately deployed what troops he had on hand, roughly equal in number to the British, many of these were poorly-trained militia.

Fearing that the British would dig in and become inextricable, Montcalm decided to attack before reinforcements could arrive from the lines to the north, even though this would have given him a great numerical advantage.

The battle was simple. The French marched up to close range while the British held their fire; both sides exchanged two massive volleys, in which the less-well-trained French buckled and withdrew to the city.

As the British pursued, they were nearly taken in the rear by reinforcements coming from the south, but a quick action held them off. Reinforcements from the north were also beaten back, leaving Quebec cut off from the bulk of the French army.

Both Wolfe and Montcalm were shot during the pursuit: Wolfe died on the battlefield, Montcalm the following day. The French military governor fled west with the majority of the army, while Quebec surrendered after a short siege.

Even with this heavy loss, the French were not defeated. They beat the British in the field the following spring and besieged Quebec, although this ended in failure when the city received reinforcements by ship.

Later that year, British forces at Quebec linked up with the expedition advancing from Lake Ontario. This gave them overwhelming superiority in numbers which, combined with free naval access to the St. Lawrence, allowed them to reduce Montreal, sealing the conquest of Canada.

1759-60 saw major British victories in every other theater: the Battle of Minden saved Hanover, a possession of George II. The twin naval victories of Lagos and Quiberon Bay destroyed a large part of the French fleet, preventing them from reinforcing Canada.

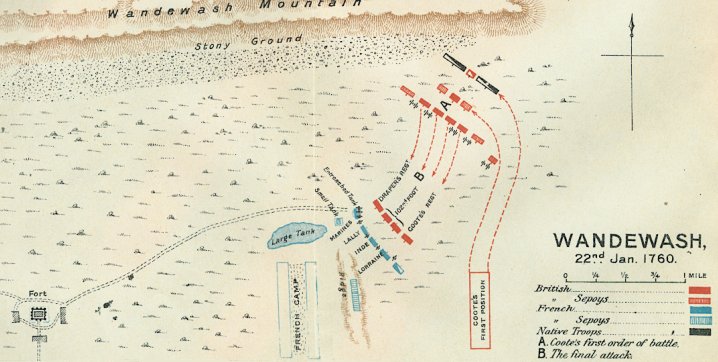

They captured Guadeloupe in 1759, then in January 1760, British and native troops defeated a French-Indian army at Wandiwash in India, leading to the fall of Pondicherry and hence French India.

Why then, amidst all this, were the Plains of Abraham so important?

Why then, amidst all this, were the Plains of Abraham so important?

Until 1759, New France claimed most of North American territory. Although not as accessible as by sea as the Thirteen Colonies, it spanned the waterways that cut through the continent, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

More specifically it gave them control of the Mississippi. It is this, with its vast tracts of fertile soil accessible by an extensive river network, that is the bedrock of modern American power. The alternatives were French control or a continent divided.

worldview.stratfor.com/article/geopol…

worldview.stratfor.com/article/geopol…

But how much was that a result of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham itself?

In light of French defeats elsewhere, especially at sea, it seems as if Quebec’s fate was sealed irrespective of any single battlefield decision.

In light of French defeats elsewhere, especially at sea, it seems as if Quebec’s fate was sealed irrespective of any single battlefield decision.

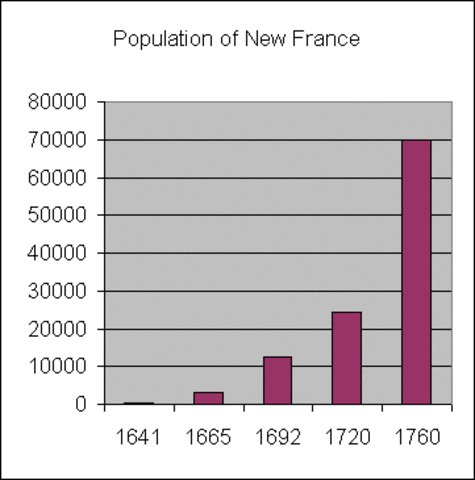

And even if it held out through the war, the long-term trends were against it. The Royal Navy still controlled the waves, and the Thirteen Colonies had a much larger population, roughly twenty times all of New France.

Yet none of these three factors—the immediate outcome of the war, long-term military prospects, or long-term demographic trends—were foreordained. Things could have played out very differently.

Battlefield defeats elsewhere only narrowed French commitments. India was lost by 1761 and there were no great prospects in Germany—they could put all their efforts into retaining their North American possessions.

If Canada had held out, this would have only spurred the French to save their colony—as it was, they managed to send a small expedition to Newfoundland in spring 1762.

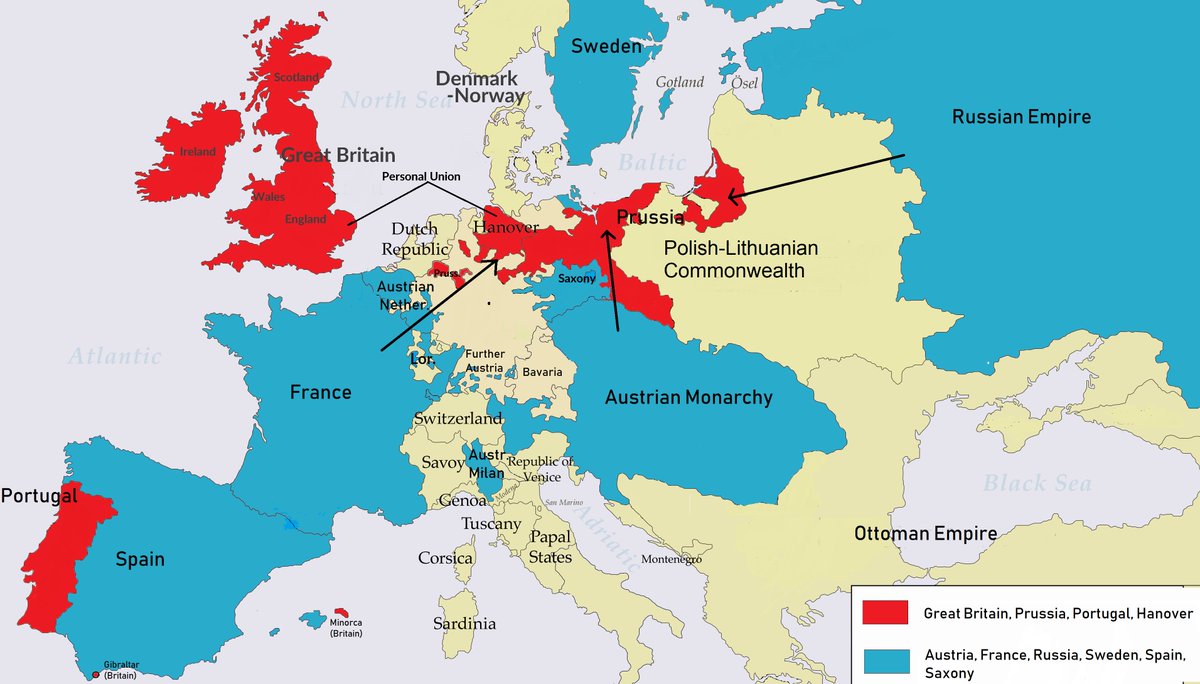

The British, for their part, had good reason to settle. The war was getting enormously expensive, especially as it was forced to subsidize Prussia, which was losing to a formidable Austrian-Russian alliance. They might well have been satisfied with much more limited gains.

This is demonstrated by the fact that, even after their continued victories in the 1760s, they were willing to return rich Guadeloupe and Pondicherry to France and allow it to retain Louisiana west of the Mississippi (which had secretly been ceded to Spain).

Nor were the long-term trends necessarily fatal. In hindsight, we see Britain as a natural naval power and France as a natural land power. Yet that advantage was only relative: France consistently had the largest army and the second-largest navy.

It’s arguably that these competing priorities that prevented France from winning decisively in either domain. When France focused heavily on the navy, as during the American Revolution, it was victorious (this was Paul Kennedy’s thesis in ‘Rise and Fall of the Great Powers’).

Already by the time of the Seven Years’ War, France had pivoted more toward the naval theater. Her inability to profit from her battlefield victories in the War of the Austrian Succession convinced her not to contest the perennial battleground of Flanders.

This allowed for a realignment of alliances on the continent. France formed an alliance with Austria, which controlled Flanders, and without any threat from the south, that other great sea power—the Dutch—stayed neutral.

Combined with an alliance with Bourbon Spain, France was freed from fighting on fronts that traditionally demanded most of her resources. Her only European commitments were in Germany, where she supported Austria and attacked Hannover—a possession of the British king.

The French fleet meanwhile underwent a modernization. By 1775 it was close in size to the Royal Navy and many of its ships more advance; it also had fewer commitments around the world, allowing it to concentrate in greater strength if carefully employed.

At the same time that France was making peace with traditional enemies, Britain was stirring resentment. Her startling ascendancy abroad threatened other colonial powers’ interests, both in the Far East and Caribbean.

This ultimately led to Britain facing the combined navies of France, Spain, and Holland in the global conflict that raged from 1778 to 1783 alongside the American Revolution.

The greatest challenge for the French was demographic. At the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War, the total population of New France, from the Mississippi Delta to the St. Lawrence, was about 70,000—around one twentieth the Thirteen Colonies.

But long-term demographic trends are hard to predict. Quebec had long taken extraordinary efforts to encourage birth rates and immigration, growing from a very small base population.

This trend was likely to accelerate as Canadian settlers pushed south of the Great Lakes and into the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, a vast expanse of fertile soil that stretched all the way to New Orleans.

And it would have only increased if the Crown poured efforts into militarizing the frontier. Chains of forts required extensive networks of support, which drew commerce and hence settlement.

The military balance was moreover tilted by the Native population, which had traditionally largely sided with France. Army sizes on the frontier were small, so this ended up being a disproportionate advantage.

Taken altogether, a different outcome at the Plains of Abraham would have left open the fate of North America. If the continent was not ultimately divided, it is possible that a protracted struggle could have lasted even into the 20th century.

This, more than anything else, could have altered the course of history. Although great powers expand and contract, they always retain the potential to shape world events so long as they remain intact.

France itself was always poised to disrupt the European balance of power, whether under a king like Louis XIV, a republican like Robespierre, or an emperor like Napoleon.

Same with Russia and China in their Imperial, Communist, or modern incarnations.

Same with Russia and China in their Imperial, Communist, or modern incarnations.

Many of these blocs were established by the outbreak of the 7YW, or were about to be. China had reached its modern borders, Russia was ascendant, most of the Americas south of the Rio Grande were Spanish, while the EIC was beginning its expansion in India.

Only the fate of North America was truly up in the air. European history would look very different if France’s subsequent military efforts were channeled here. Or if the American Revolution never happened. Or if there was never a single North American superpower.

None of this is to say that New France would have won out, or even endured. But it is to say that it was a possibility, one which was only foreclosed on the Plains of Abraham.

Few other battles in world history can claim to be anywhere near that decisive.

Few other battles in world history can claim to be anywhere near that decisive.

@SashoTodorov1 ...a revolutionary regime declares war on all Europe in 1792. Hence why demographics is the most important factor...but as noted, a lot of things can change over the span of decades.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh