Who was the greatest artist of the 20th century?

People talk about Picasso and Dalí, but here's a name you probably haven't heard: Hasui Kawase, the last master of Japanese ukiyo-e.

It sounds oddly specific, but no other artist in history was so good at depicting the weather...

People talk about Picasso and Dalí, but here's a name you probably haven't heard: Hasui Kawase, the last master of Japanese ukiyo-e.

It sounds oddly specific, but no other artist in history was so good at depicting the weather...

There's a world in which Hasui Kawase never existed.

He was born as Bunjiro Kawase in 1883 and though art was his passion, Bunjiro was supposed to take over his father's business.

Until his sister and her husband eventually took over instead...

He was born as Bunjiro Kawase in 1883 and though art was his passion, Bunjiro was supposed to take over his father's business.

Until his sister and her husband eventually took over instead...

So Bunjiro was free to study painting, first under the Western-style artist Okada Saburosuke and then the traditional Japanese-style artist Kaburagi Kiyokata.

And it was Kiyokata who, according to custom, gave the young man his own artist's name — Hasui.

A legend was born.

And it was Kiyokata who, according to custom, gave the young man his own artist's name — Hasui.

A legend was born.

Hasui became involved in the "shin-hanga" (new prints) movement, working with the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo.

Whereas some Japanese artists pursued western methods alone, Hasui sought rather to preserve Japanese methods and combine them with elements from western art.

Whereas some Japanese artists pursued western methods alone, Hasui sought rather to preserve Japanese methods and combine them with elements from western art.

Ukiyo-e is the broad name for the traditional Japanese art of woodblock printing.

It was a multi-staged, collaborative process involving designer, engraver, printer, and publisher.

Hokusai and Hiroshige, both active in the 19th century, are the most famous ukiyo-e artists.

It was a multi-staged, collaborative process involving designer, engraver, printer, and publisher.

Hokusai and Hiroshige, both active in the 19th century, are the most famous ukiyo-e artists.

Hasui started designing ukiyo-e, focussing almost exclusively on landscapes.

He travelled around Japan, preferring to see things for himself rather than base his designs on photographs or the work of other artists.

And it shows — he captured the essence of every place he went.

He travelled around Japan, preferring to see things for himself rather than base his designs on photographs or the work of other artists.

And it shows — he captured the essence of every place he went.

Many Japanese artists of his generation had been influenced by the Impressionists in Europe — who had themselves originally been influenced by the likes of Hiroshige and Hokusai!

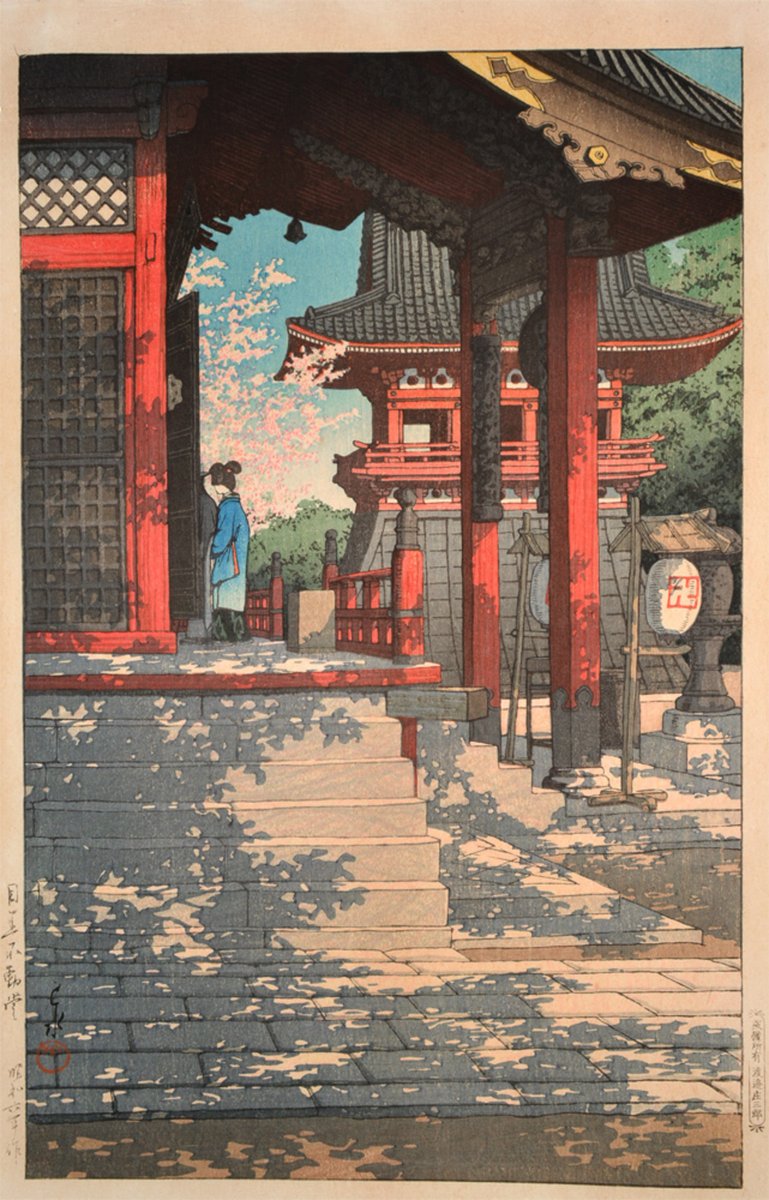

Hasui had Impressionist traits, especially in his near-perfect sensitivity to the effects of light.

Hasui had Impressionist traits, especially in his near-perfect sensitivity to the effects of light.

But he took this further.

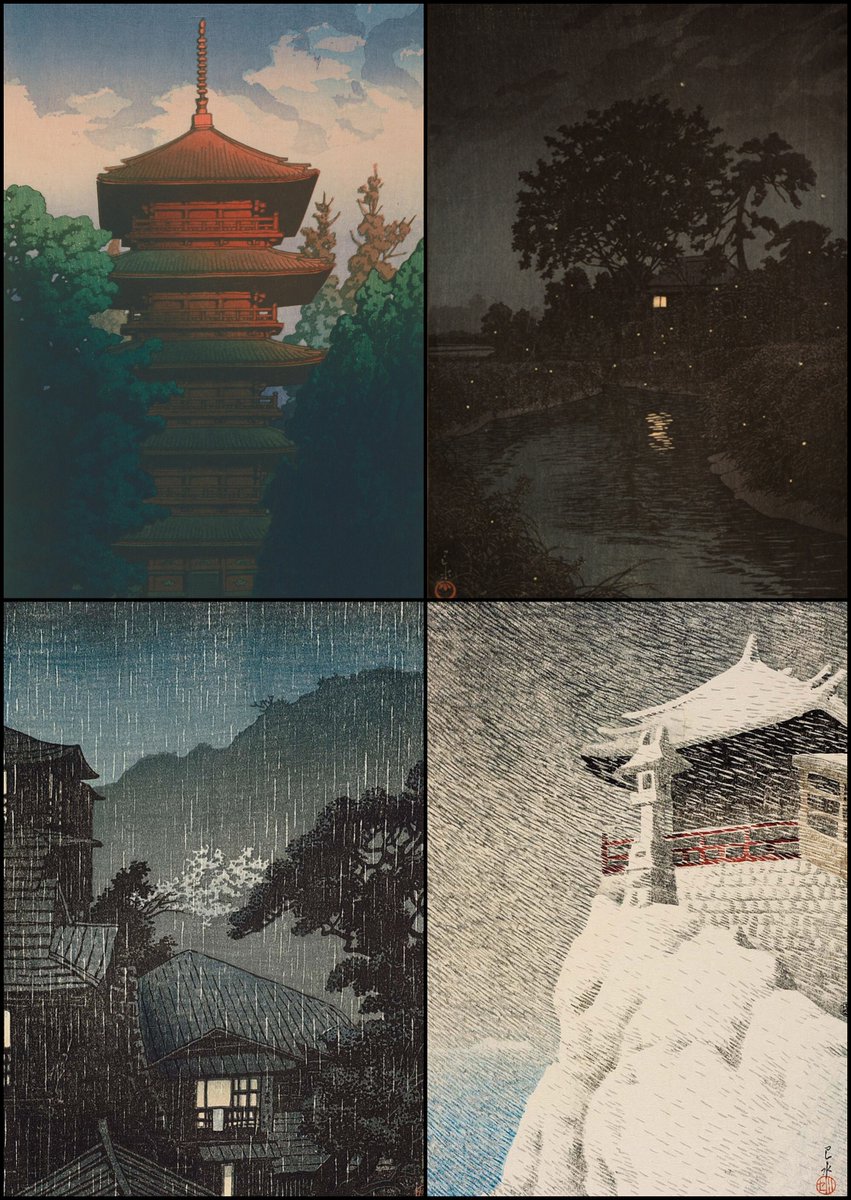

Notice how you can immediately tell the time of day and identify the weather in any of his prints.

This sounds simple, but it really isn't. To do so requires both scrupulous observation of the real world and absolute command of light, colour, & shape.

Notice how you can immediately tell the time of day and identify the weather in any of his prints.

This sounds simple, but it really isn't. To do so requires both scrupulous observation of the real world and absolute command of light, colour, & shape.

Rain is notoriously difficult to depict in art, but for Hasui it offered no trouble whatsoever.

With a few pale lines and careful control of lighting he gives the impression either of a gentle shower or violent downpour.

It sounds silly, but Hasui's rain always *looks wet*.

With a few pale lines and careful control of lighting he gives the impression either of a gentle shower or violent downpour.

It sounds silly, but Hasui's rain always *looks wet*.

Hasui could also conjure the heat of midday or the warm glow of an autumn afternoon.

By paying such careful attention to the real scene before him and then simplifying its elements, Hasui was able to create highly evocative landscapes which feel, somehow, both real and timeless.

By paying such careful attention to the real scene before him and then simplifying its elements, Hasui was able to create highly evocative landscapes which feel, somehow, both real and timeless.

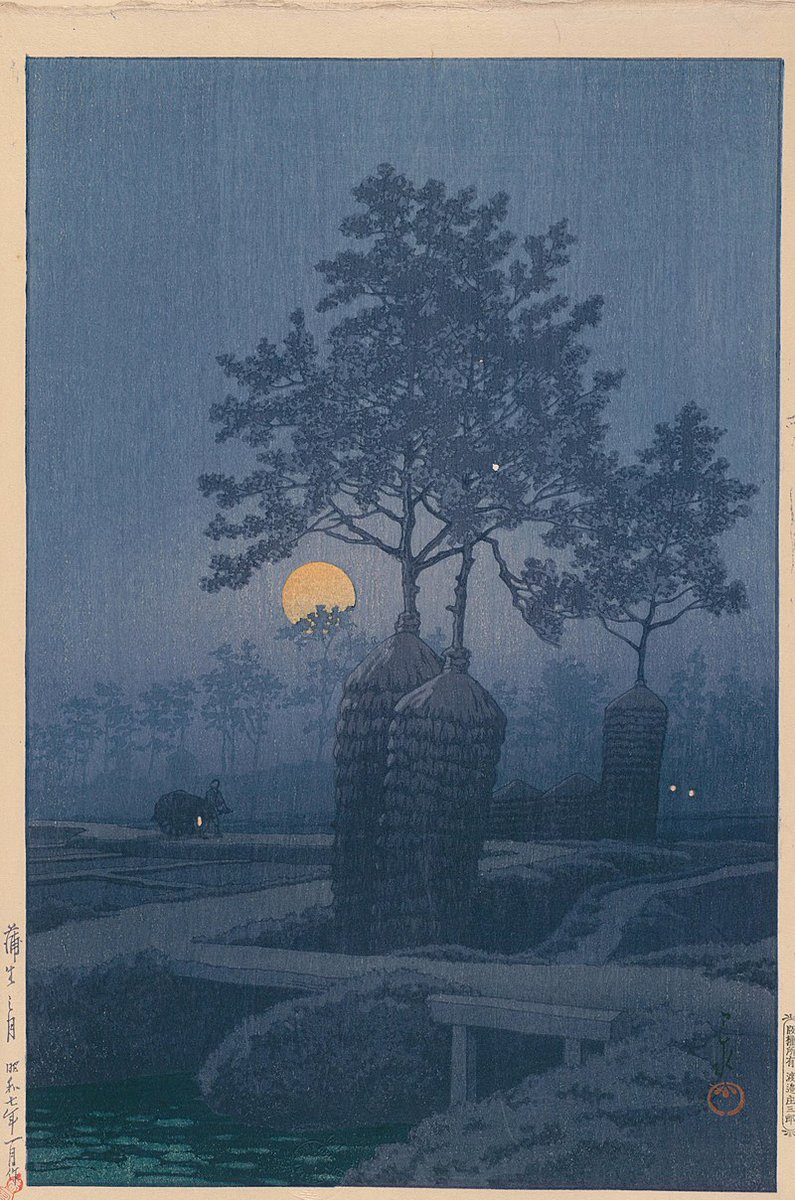

Hasui, though a man who evidently loved bright colours, was equally at home in the darkness of night.

A sole lighted window, silhouetted mountains, glinting reflections — he knew which details contained the essence of any given scene.

You can almost *hear* Hasui's landscapes.

A sole lighted window, silhouetted mountains, glinting reflections — he knew which details contained the essence of any given scene.

You can almost *hear* Hasui's landscapes.

Look at the subtlety of his sunrises & sunsets — the gentle gradation of colour and shadow is enough to make them feel more like dawn or dusk than any photograph ever could.

He even worked with printers to create different versions of the same scene at different times of day.

He even worked with printers to create different versions of the same scene at different times of day.

It was for his snow prints that Hasui became, perhaps understandably, most famous.

Though rooted in the tradition of Hiroshige and Hokusai, Hasui blended just enough Western influence — especially in lighting and modelling — to create a style and atmosphere never before seen.

Though rooted in the tradition of Hiroshige and Hokusai, Hasui blended just enough Western influence — especially in lighting and modelling — to create a style and atmosphere never before seen.

The result of Hasui's mastery over light and weather is that his prints are intensely atmospheric; the viewer gets a visceral sense of the landscape before them.

But it isn't merely "realistic" — Hasui imbues these scenes with mood, mystery, beauty, and delight.

But it isn't merely "realistic" — Hasui imbues these scenes with mood, mystery, beauty, and delight.

This is partly because Hasui was also a master of composition; he knew how to make an image "feel right".

Whether castles, valleys, dockyards, bridges, or mountains, Hasui always found the right angle to give us a perfectly evocative snapshot of the place he was visiting.

Whether castles, valleys, dockyards, bridges, or mountains, Hasui always found the right angle to give us a perfectly evocative snapshot of the place he was visiting.

And it also has something to do with Hasui's tendency to add, at most, one or two solitary figures to his prints.

Whether working, travelling, bathing, or strolling, these people transform Hasui's landscapes into something *more* — quiet stories unfolding before our eyes.

Whether working, travelling, bathing, or strolling, these people transform Hasui's landscapes into something *more* — quiet stories unfolding before our eyes.

This is how Hasui described his creative process:

"I do not paint subjective impressions. My work is based on reality. I can not falsify but I can simplify."

Unlike many other 20th century artists, Hasui was interested in outward reality, and he wanted to convey its beauty.

"I do not paint subjective impressions. My work is based on reality. I can not falsify but I can simplify."

Unlike many other 20th century artists, Hasui was interested in outward reality, and he wanted to convey its beauty.

There is a serenity and purity to his art which few other artists in the 20th century ever matched; we become lost in his worlds... and we *want* to become lost in them.

You can see why Hasui was proclaimed a National Living Treasure in Japan toward the end of his life.

You can see why Hasui was proclaimed a National Living Treasure in Japan toward the end of his life.

And so, with his love for nature, his sensitivity to light and colour, his impeccable sense of composition, his command of atmosphere, and his poetic sensibilities, Hasui Kawase surely deserves to be mentioned in any conversation about the greatest artists of the 20th century.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter