When you hear the word "Brutalism", what do you think of?

Perhaps something like this: a rather uninspiring array of highrises, the sort of which people tend to call miserable, soulless, and oppressive.

But that *isn't* Brutalism, and never has been...

Perhaps something like this: a rather uninspiring array of highrises, the sort of which people tend to call miserable, soulless, and oppressive.

But that *isn't* Brutalism, and never has been...

Brutalism has become a byword for any modern architecture whose primary construction material is concrete.

But that would be like saying Gothic Architecture is anything built from stone, or that Islamic Architecture is anything which uses ceramic tiling for decoration.

Not so.

But that would be like saying Gothic Architecture is anything built from stone, or that Islamic Architecture is anything which uses ceramic tiling for decoration.

Not so.

That being said, Brutalism is intimately linked to concrete. Its name partly comes from the French term "béton brut", meaning "raw concrete", as used by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier.

But the use of concrete is only one part of the story of Brutalism.

But the use of concrete is only one part of the story of Brutalism.

Although its origins can be traced back to the first decades of the 20th century with modernist architects in Austria and Germany — Loos, the Bauhaus, Le Corbusier — it only properly appeared after the Second World War.

And there's a very good reason for that.

And there's a very good reason for that.

Within one lifetime the world had torn itself to pieces twice.

You can see why people felt things needed to change, so as never to repeat those mistakes — architecture was part of this process.

Not to forget that population was booming and thousands of cities needed rebuilding.

You can see why people felt things needed to change, so as never to repeat those mistakes — architecture was part of this process.

Not to forget that population was booming and thousands of cities needed rebuilding.

And so Brutalism was a fundamentally *optimistic* style.

Its stark difference with the architecture of the recent past was about creating a new world; one that was fairer, more proserous, and more peaceful.

After the horrors of WWII, Brutalism had faith that we could rebuild.

Its stark difference with the architecture of the recent past was about creating a new world; one that was fairer, more proserous, and more peaceful.

After the horrors of WWII, Brutalism had faith that we could rebuild.

The use of concrete in post-war construction was inevitable, because economic and social pressure meant that people had to build as cheaply and effectively as possible.

And Brutalism was about doing so in the most imaginative way possible; making the most of the situation.

And Brutalism was about doing so in the most imaginative way possible; making the most of the situation.

And rather than hiding the real nature of its primary construction material, Brutalist buildings proudly display their concrete.

In the same way that Gothic cathedrals were built from blocks of stone and did not hide this fact behind façades of marble.

Architectural honesty.

In the same way that Gothic cathedrals were built from blocks of stone and did not hide this fact behind façades of marble.

Architectural honesty.

And, stylistically, Brutalism was about exploiting the strengths of concrete.

With its monumental forms and bold, exciting shapes, Brutalism aspired to make the world *more interesting*.

With its monumental forms and bold, exciting shapes, Brutalism aspired to make the world *more interesting*.

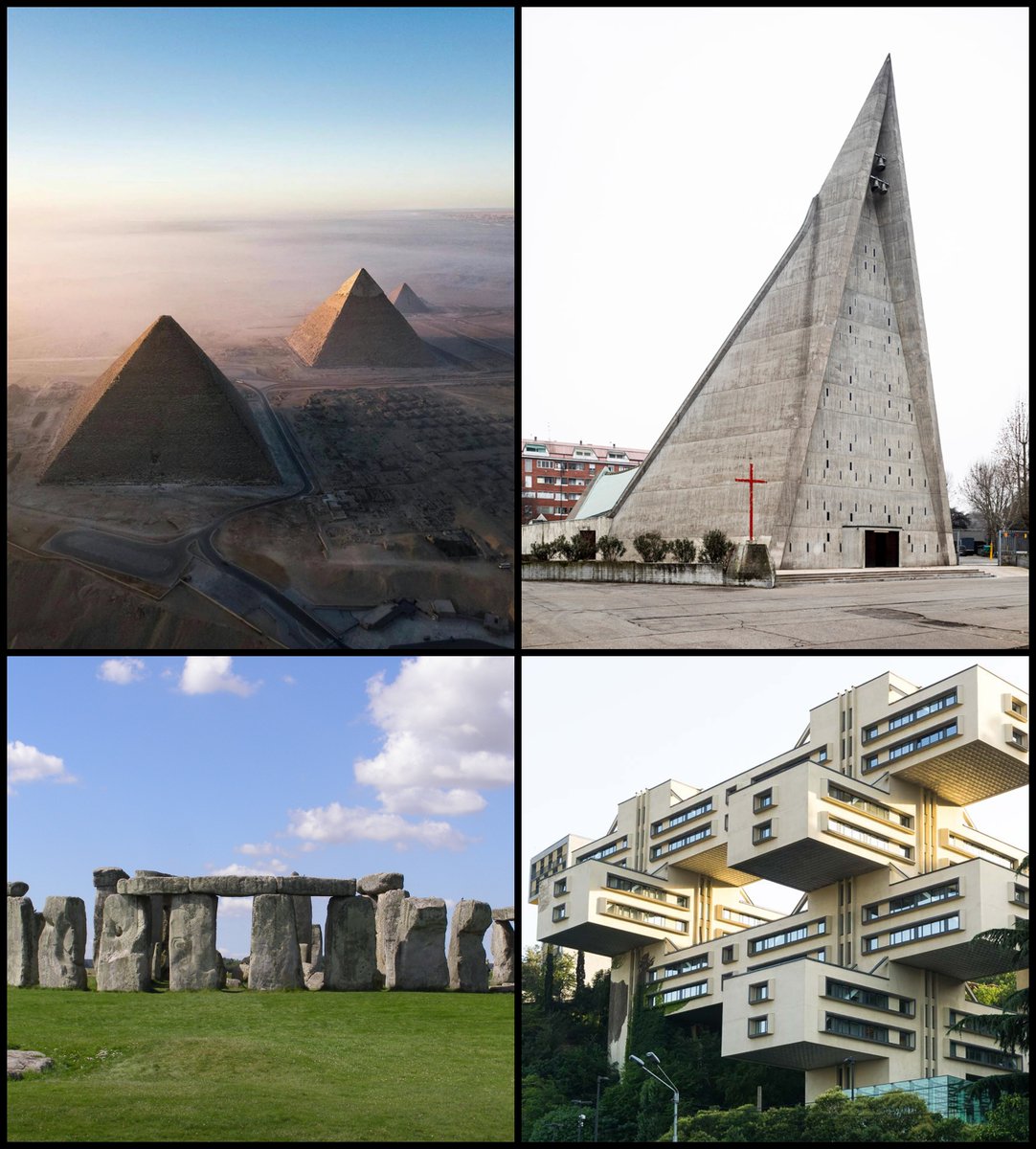

And, strangely, Brutalism harks back to the oldest of all human architecture.

Its massiveness and monolithic geometry have more in common with the Pyramids of Ancient Egypt or England's prehistoric Stonehenge than with modernist skyscrapers.

Its massiveness and monolithic geometry have more in common with the Pyramids of Ancient Egypt or England's prehistoric Stonehenge than with modernist skyscrapers.

Hate it or love it, this is architecture with an opinion.

And though people have said many things about proper Brutalism, nobody has ever called it boring:

And though people have said many things about proper Brutalism, nobody has ever called it boring:

Something like Trellick Tower in London, built in 1972 and designed by Ernő Goldfinger, is often held up as an example of Brutalism.

That is true in some sense, but as you can tell from the other buildings shared here, Trellick Tower represents its most watered-down form.

That is true in some sense, but as you can tell from the other buildings shared here, Trellick Tower represents its most watered-down form.

And so Trellick Tower is not True Brutalism.

It may have been cheap and effective, but it was shorn of the aesthetic boldness, the stylistic optimism, and the great sense of elemental excitement.

Trellick Tower, like many other postwar highrises, *is* boring architecture.

It may have been cheap and effective, but it was shorn of the aesthetic boldness, the stylistic optimism, and the great sense of elemental excitement.

Trellick Tower, like many other postwar highrises, *is* boring architecture.

Such plain modernism is the direct precursor to much of the world's current architecture: it doesn't have an opinion, simply does its job, and tries not to be noticed.

Maybe we can credit it for that, but such plastic-clad buildings have made the world a less interesting place.

Maybe we can credit it for that, but such plastic-clad buildings have made the world a less interesting place.

Another important part of Brutalism, which has been largely forgotten, is the importance of its interior design.

Large spaces filled with light and air, not the gloomy corridors of so much other postwar architecture.

Large spaces filled with light and air, not the gloomy corridors of so much other postwar architecture.

Brutalist architects were also perfectly aware of the monotonous colour and texture of concrete.

Hence they chose to offset all that greyness with rich interior colour and texture: carpets, parquet floors, wooden furniture, metal fixtures, or stained glass.

Hence they chose to offset all that greyness with rich interior colour and texture: carpets, parquet floors, wooden furniture, metal fixtures, or stained glass.

Brutalism is also peculiarly suited to greenery, perhaps more so than any other architectural style.

A plain concrete structure is one thing, but when clad in trees, bushes, vines, and flowers, it suddenly looks more akin to the wild rocks of a mountainscape.

A plain concrete structure is one thing, but when clad in trees, bushes, vines, and flowers, it suddenly looks more akin to the wild rocks of a mountainscape.

There were many phases of Brutalism and it flourished at different times in different countries.

In the USSR, for example, it caught on later than the rest of the world. And in Brazil, led by Oscar Niemeyer, it developed into a unique form sometimes called "Tropical Brutalism".

In the USSR, for example, it caught on later than the rest of the world. And in Brazil, led by Oscar Niemeyer, it developed into a unique form sometimes called "Tropical Brutalism".

Nobody is obliged to enjoy an architectural style, and to dislike Brutalism is perfectly justifiable.

But Brutalism has been unfairly maligned because of guilt-by-assocation with other forms of modernist architecture.

At least let us criticise it for what it actually is.

But Brutalism has been unfairly maligned because of guilt-by-assocation with other forms of modernist architecture.

At least let us criticise it for what it actually is.

And the tragedy is that whereas so many unobtrusive but boring buildings have survived, Brutalist architecture is being demolished — an era of socio-economic and cultural history destroyed.

Even if we don't like it, Brutalism is surely worth preserving because of its uniqueness.

Even if we don't like it, Brutalism is surely worth preserving because of its uniqueness.

In an age of insipid architecture and bland urban design, Brutalism offers a modernist alternative which is bold, exciting, optimistic, has a view of the world, and at least tries to be interesting.

So, should we give it a second chance?

So, should we give it a second chance?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh