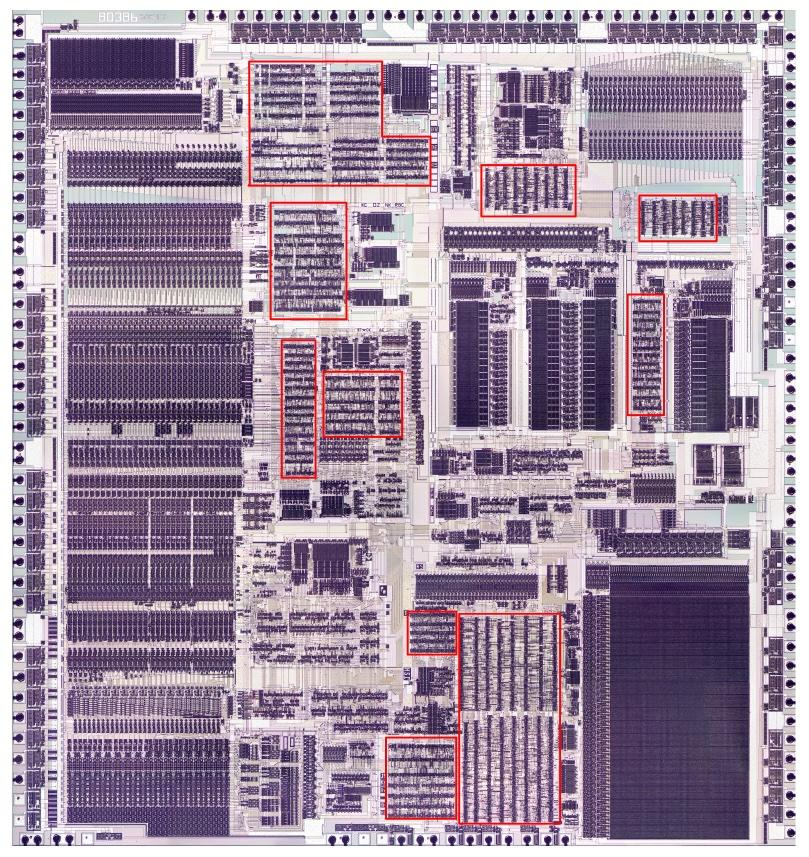

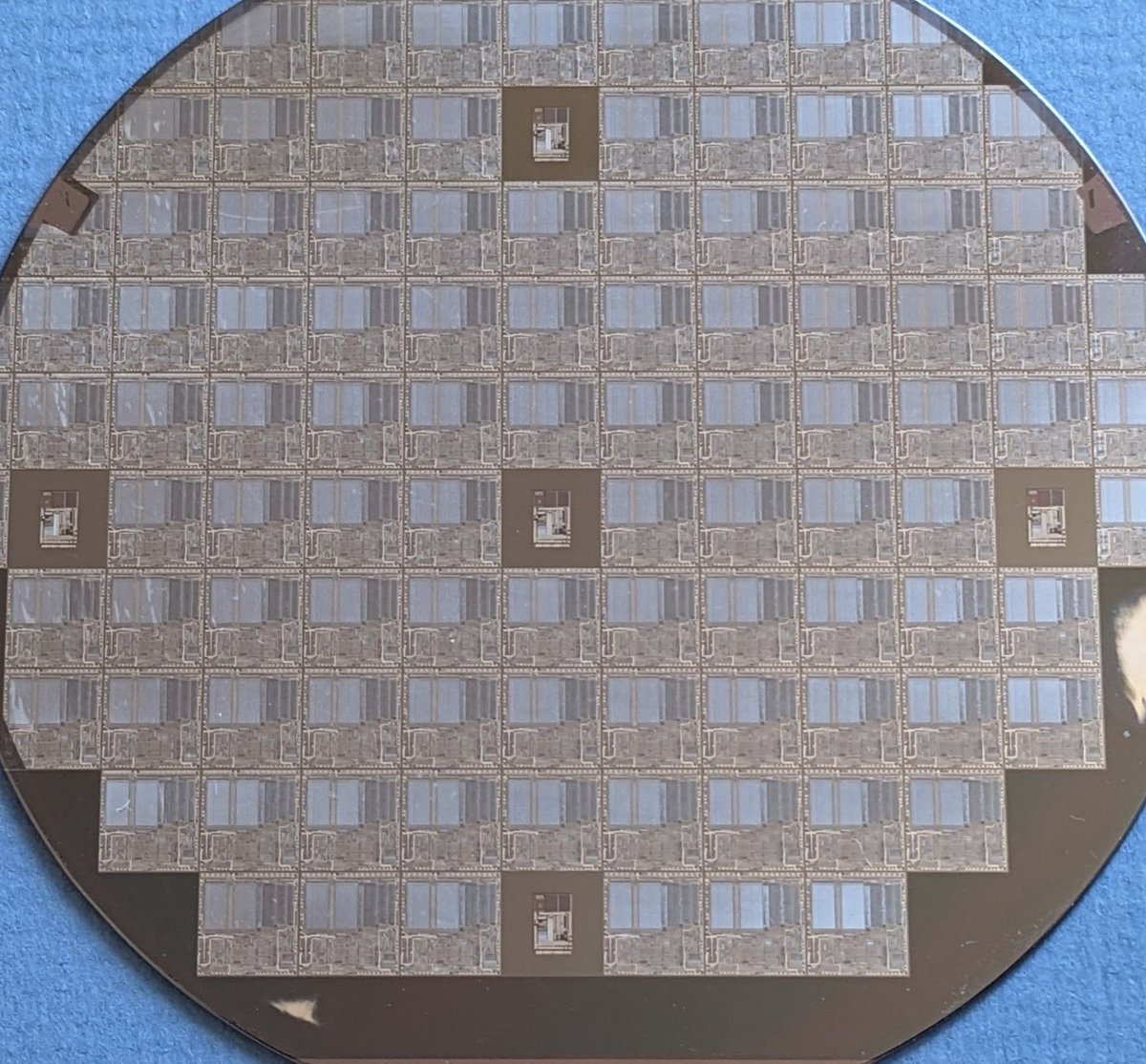

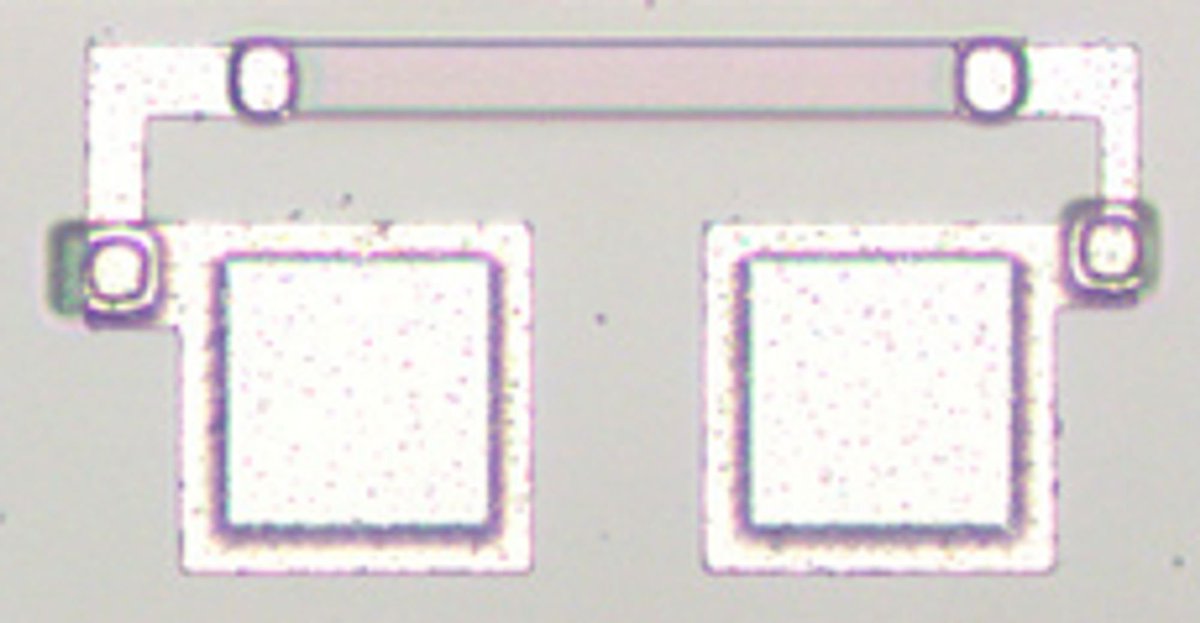

Credits: thanks to @Siliconinsid for the die images. The wall-sized 386 photo is from Intel's 1985 annual report. Thanks to Pat Gelsinger who sent me copies of his 1985 papers on the 386. 9/9

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh