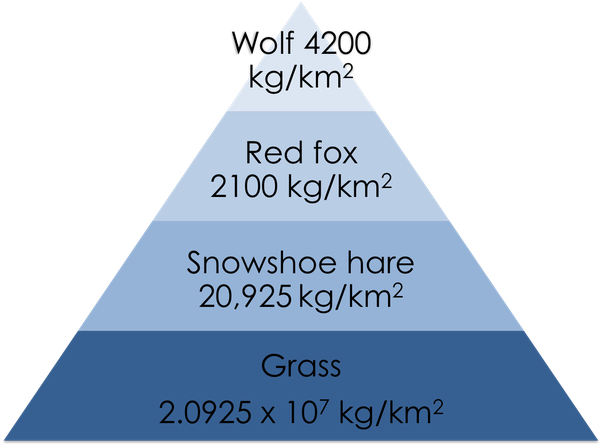

Somehow we all get the idea of biomass pyramid

There's more plants than herbivores, more herbivores than carnivores etc. The lower trophic levels weigh more. And "more" means few orders of magnitude more

Perhaps, we need to introduce an idea of a technology chain pyramid 🧵

There's more plants than herbivores, more herbivores than carnivores etc. The lower trophic levels weigh more. And "more" means few orders of magnitude more

Perhaps, we need to introduce an idea of a technology chain pyramid 🧵

https://twitter.com/Ulfberht75/status/1717891428435562600

Consumer goods would constitute the lowest trophic level. Which means, the largest level by far. There's just way more of them compared all the upper levels combined

This is also the only level of the technology chain visible to the general audience

This is also the only level of the technology chain visible to the general audience

"Everything produced in China" means "everything I buy is produced in China". And everything I buy means consumer goods

1. We see only the lowest trophic level of the technology chain

2. We notice it is dominated by the Chinese production

3. Voila, China produces everything

1. We see only the lowest trophic level of the technology chain

2. We notice it is dominated by the Chinese production

3. Voila, China produces everything

Data seems to support this idea. Indeed, Chinese manufacturing output may exceed the output of Europe + next few major industrial powers combined

That is because the upper trophic levels are just as invisible to the statistics as they are to the human eye

They are just small

That is because the upper trophic levels are just as invisible to the statistics as they are to the human eye

They are just small

Metalworking tools constitute principal industrial equipment for any manufacturing industry. Japan is the world's second largest exporter, almost on pair with Germany. And yet, machine tool industry makes for less than 2% of its manufacturing output

The upper levels are small

The upper levels are small

That makes the upper levels of the production chain completely invisible in the aggregate data. They're just very much smaller than the lower levels they feed off

Market of spoons > market of spoon producing machines

for the same reason there's more phyto- than zooplankton

Market of spoons > market of spoon producing machines

for the same reason there's more phyto- than zooplankton

Aggregation makes the upper levels of economy invisible for the same reason it makes invisible the upper levels of the trophic pyramid. There is way more grass than rabbits, there's way more frying pans than turning machines

Aggregation -> The structure lost

Aggregation -> The structure lost

Now the thing with the upper levels is that they tend to be not only quantitatively smaller than the lower levels (-> hence invisibility), but also qualitatively different

More knowledge intensive

More tacit knowledge (craftsmanship) intensive

Harder to pick up

The bottleneck

More knowledge intensive

More tacit knowledge (craftsmanship) intensive

Harder to pick up

The bottleneck

Let's zoom in to something bottleneckish. The pressing die production could be a good example

Here is an Audi. What is interesting about the Audi is that it may have been one of the top metalworkers on the world

Here is an Audi. What is interesting about the Audi is that it may have been one of the top metalworkers on the world

How do you make its car body elements? Most probably, you will:

1. Take a sheet of metal and feed it into a pressing machine

2. Machine it with a mill etc. to give it precise form and dimensions

3. Assemble it all

1, 2 and even 3 may be automatable

1. Take a sheet of metal and feed it into a pressing machine

2. Machine it with a mill etc. to give it precise form and dimensions

3. Assemble it all

1, 2 and even 3 may be automatable

Pressing is automatable. You feed a sheet of metal into a CNC press and, kaboom, it is formed into the shape

Machining is automatable. Your CNC machine tool cuts off the excess metal from a workpiece giving it precise form and dimensions

Now what is un-automatable? Production of a pressing die

This is a bottleneck of a bottleneck. Each pressing die gives its impression to thousands of doors, etc. Every die error will be scaled up thousandfold

Dies are fixed manually, with fingers. That is semi-artisanal labor

This is a bottleneck of a bottleneck. Each pressing die gives its impression to thousands of doors, etc. Every die error will be scaled up thousandfold

Dies are fixed manually, with fingers. That is semi-artisanal labor

Craftsman expertise like this cannot be bought. You can only grow it, in the process of one on one mentorship, taking years

Can you do without it? You can. You will probably end up with the lower quality dies -> lower quality product

Lots of defects, same on every car

Can you do without it? You can. You will probably end up with the lower quality dies -> lower quality product

Lots of defects, same on every car

So what did we learn? We dived in into the production of some of the most sophisticated consumer goods there are. We observed a bottleneck in this process (pressing die)

And in this bottleneck we found the manual, craftsman labor based on a semi-artisanal expertise

And in this bottleneck we found the manual, craftsman labor based on a semi-artisanal expertise

Now you may ask:

But is it really necessary to have all this artisanal expertise to produce a car? 🤔

Of course, not. The skills you may observe here are vastly excessive compared with the bare minimum necessary to produce a car that drives (and that you can sell at a profit)

But is it really necessary to have all this artisanal expertise to produce a car? 🤔

Of course, not. The skills you may observe here are vastly excessive compared with the bare minimum necessary to produce a car that drives (and that you can sell at a profit)

And that is exactly the thing with Western Europe

It is excessive

It is excessive architecturally. You may notice it when visiting old European towns. There's just lots of stuff out there that has magically survived through all the political turmoils

Very un-optimized

It is excessive

It is excessive architecturally. You may notice it when visiting old European towns. There's just lots of stuff out there that has magically survived through all the political turmoils

Very un-optimized

It is excessive intellectually, excessive in terms of skills and craftsmanship. Carrying the uninterrupted tradition since the earliest days of Industrial Revolution, it is the largest reservoir of niche and unobvious manufacturing competences by far

Again, very un-optimized

Again, very un-optimized

I have been long puzzled by how widespread is contempt to Europe in the United States. I used to find this attitude exaggerated and almost performative

Now I tend to explain it with the un-optimized character of the European industry and economy in general

Now I tend to explain it with the un-optimized character of the European industry and economy in general

Excessive rather than optimised, driven by the craftsman more than entrepreneurial spirit, accumulating a great deal of obscure, niche knowledge, European industry may not be very efficient in terms of money making

You won't sell that much, if you insist on producing on your own terms

You won't sell that much, if you insist on producing on your own terms

But

If a foreign martial state aims to produce something niche and unobvious

(like and intercontinental ballistic missile)

then it will have little choice but to outsource much of the production chain

(specifically its upper levels)

to the best craftsmen there are

If a foreign martial state aims to produce something niche and unobvious

(like and intercontinental ballistic missile)

then it will have little choice but to outsource much of the production chain

(specifically its upper levels)

to the best craftsmen there are

The end

I will post a full version in my newsletter kamilkazani.substack.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh