This Day in Labor History: October 27, 1948. An air inversion trapped the pollution spewed out by U.S. Steel-owned factories in Donora, Pennsylvania. The Donora Smog killed 20 people and sickened 6000 others. Let's talk about this environmental horror spawned by corporations!

That picture above was taken at noon on the day.

This event was one of the most important toxic events in the postwar period that sparked the rise of the environmental movement and groundbreaking legislation to protect Americans from the worst impacts of industrialization.

Donora was a town dominated by U.S. Steel. Southeast of Pittsburgh, the town had both the Donora Zinc Works and the American Steel and Wire plant, both owned by U.S. Steel.

The pollution throughout southwest Pennsylvania was legendary as the combination of the steel industry and the region’s hills and valleys meant incredible smoke.

While Pittsburgh was nationally famous for its pollution, surrounding towns had similar problems. For the 19th and first half of the twentieth century, this pollution was seen as a sign of progress.

But after World War II, with the struggles for mere survival that marked American labor history for the previous century over, workers began demanding more of their employers and government when it came to the environment.

The factories routinely released hydrogen fluoride, sulfur dioxide, sulfuric acid, nitrogen dioxide, fluorine, and other poisons into the air. Nearly all the vegetation within a half mile of the Zinc Works was already dead.

Donora already suffered from high rates of respiratory deaths, a fact noted at the time, which is significant because people didn’t much talk about that in 1948. The people who had to deal with these problems were the workers themselves.

The companies poisoned their bodies inside the factories through toxic exposure on the job and they poisoned their bodies outside the factories through air, water, and ground pollution.

Being an industrial worker in mid-twentieth century America was to be under a constant barrage of toxicity.

In Donora, people had been complaining about the air quality for decades. U.S. Steel opened the American Steel and Wire plant in 1915.

By 1918, it was already paying people off for the air pollution and it faced lawsuits from residents, especially farmers, through the Great Depression. But in a climate of weak legal repercussions or regulation, this was merely a nuisance for U.S. Steel.

The air inversion started on October 27 and continued until November 2. When it began, this meant that the pollution spewing from the smokestacks just sat in the valley, turning the air into a toxic stew.

By October 29, the police closed the town to traffic because no one could see well enough to drive. By that time, people were getting very sick. 6000 people became ill out of a town of 13,000.

Almost all of these people were workers and their families who relied upon U.S. Steel for survival. Yet that could also kill them. 800 pets also died.

The smog could easily have been worse. An assessment released in December estimated that thousands more could have died if it lasted a couple extra days.

The weather inversion was region-wide, but Pittsburgh, avoided any serious health problems like Donora because it had recently passed new ordinances against burning bituminous coal, thus lowering the pollution levels and saving its citizens’ lives.

Alas, Donora had not passed such regulations.

U.S. Steel of course called the Donora Fog “an act of God,” because only a higher power could have led to a factory without pollution controls. This is standard strategy for corporations when their environmental policies kill people.

The Donora Fog put U.S. Steel workers, organized with the United Steelworkers of America, into a difficult situation. Six of the seven members of the Donora city council were USWA members. And they were sick too. But what if U.S. Steel closed the factories?

Even in 1948, this was already on workers’ minds. Yet they also wanted real reform. Workers did not trust federal and state regulators. The U.S. Public Health Service originally rejected any investigation of Donora, calling it an “atmospheric freak.”

When investigations finally did happen a few days later, there were no air samples from the pollution event itself and the government recommended the factories reopen.

So the USWA and city council filled with its own members conducted their own investigation. CIO president Phil Murray offered the locals $10,000 to start this process.

Working with a medical school professor from the University of Cincinnati, the USWA hired six housewives to conduct health effects survey to create the basis for a lawsuit. This continued pressure finally forced a government response.

When the Zinc Works decided to reopen in order to “prove” that the plant could not possibly cause smog, locals pressured the Public Heath Service to make the test public.

When it did, the health complaints started rolling in, with parents keeping their children home from school.

Ultimately, the Public Health Service had no interest in holding U.S. Steel accountable for their subsidiary plants and the company itself wanted to avoid liability without creating a new regulatory structure that would limit emissions.

U.S. Steel openly claimed they would close the plants if it had to make major reforms. And in the end, the Public Health Service report, released in October 1949, did not pin culpability on the factories.

The people of Donora sued the plants in response. The company returned to its “act of God” legal defense. The Zinc Works lawsuit paid 80 families $235,000 when it was settled, but that barely covered their legal fees.

The American Steel and Wire suit was more successful, leading to a $4.6 million payout. But this was a still a pittance considering the damage done to the people of Donora by the steel industry.

Yet in the end, this was an industry the town also needed to survive. U.S. Steel closed both plants by 1966, leading to the long-term decline of Donora, a scenario repeated across the region as steel production moved overseas.

Today, Donora’s population is less than half what it was in 1948.

The Donora Fog helped lead to laws cleaning up the air. The first meaningful air pollution legislation in the nation’s history passed Congress and was signed by President Eisenhower in 1955. 1963 saw the first Clean Air Act and 1970 the most significant Clean Air Act.

Supporters of all these laws cited Donora as evidence of the need for air pollution legislation.

I drew from Lynn Page Snyder, “Revisiting Donora, Pennsylvania’s 1948 Air Pollution Disaster, in Joel Tarr, ed., Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region for this thread.

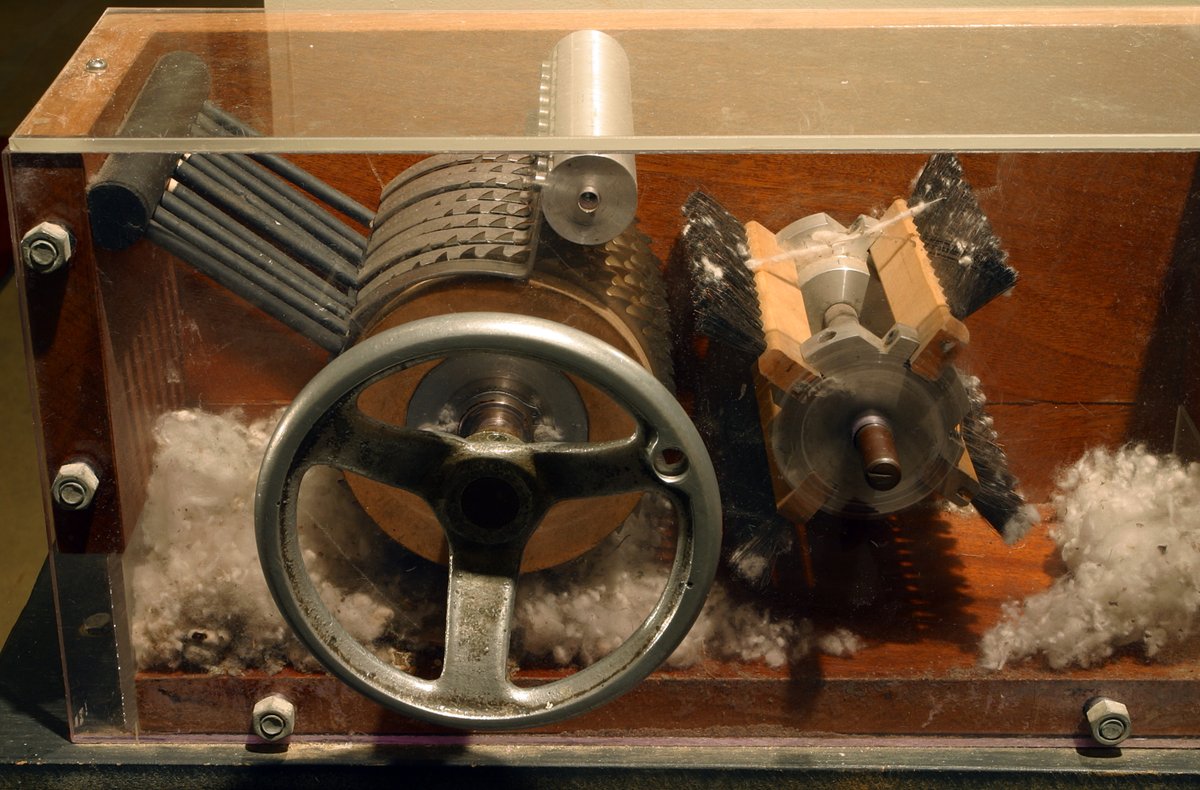

Back tomorrow to discuss the invention of the cotton gin.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter