1. Amazon is in a world of legal hurt — I just read the less-redacted version of the FTC’s monopoly lawsuit. Lots of evidence of Amazon execs knowingly screwing consumers & killing competition, aware of their own wrong-doing.

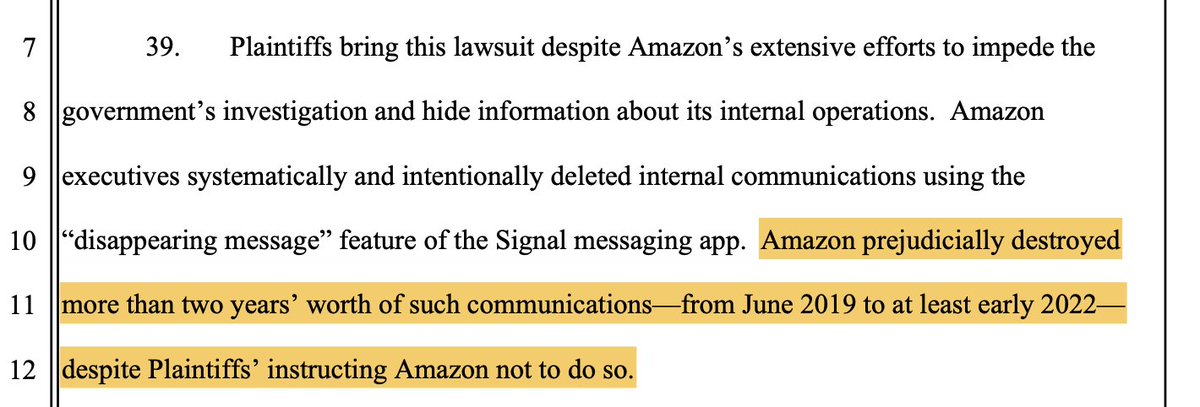

A few highlights. First, destroying evidence.

A few highlights. First, destroying evidence.

2. Here’s an exec saying that blocking sellers from offering lower prices on other sites is "a dirty job, but we need to do it."

3. This is wild — Amazon retaliates so harshly against sellers who discount elsewhere that a competing platform (maybe Walmart?), in order to attract sellers, had to create an algorithm that ensures sellers’ prices can never ever drop below what they charge on Amazon.

4. “Prices will go up,” declared Jeff Wilke, Amazon’s CEO of Worldwide Consumer, after implementing an algorithm that makes it impossible for competitors to win market share by lowering their prices.

5. Amazon's secret price-raising system, Project Nessie, fleeced at least $1 billion from shoppers.

To evade detection, Amazon turned Nessie off when attention to prices was highest, such as during the holiday season.

To evade detection, Amazon turned Nessie off when attention to prices was highest, such as during the holiday season.

6. If you control a spigot that can dump tens of millions of dollars into your lap just like that, you are a monopoly. No question.

7. Why is there no alternative to Amazon? Here’s Amazon using its price manipulation tools to kill Jet, an upstart competitor. Three months after Jet launched, it was forced to "revise [I [its] price leadership strategy…”

10. Here’s Jeff Bezos, founder of "the world's most consumer-centric company," telling executives to stuff “defect” ads in front of shoppers — ads that aren’t relevant to their search — because it’s a way to make lots of money.

12. Lots of new evidence about how Amazon thwarts competition by forcing sellers to use its fulfillment.

Amazon had an “oh crap” moment when it looked at the numbers and realized that Seller Fulfilled Prime (SFP) was undermining its monopoly control of e-commerce.

Amazon had an “oh crap” moment when it looked at the numbers and realized that Seller Fulfilled Prime (SFP) was undermining its monopoly control of e-commerce.

13. A top executive couldn’t sleep as he realized that SFP was helping independent shippers compete against Amazon.

15. Amazon moved to kill SFP after an executive learned that UPS was advertising that its fulfillment service could fulfill Prime orders.

With just the thought of having to compete on the merits, this executive was "losing [his] mind."

With just the thought of having to compete on the merits, this executive was "losing [his] mind."

16/16. Also fascinating is the fact that at every turn, there's someone inside Amazon saying "don't do this, it's bad for shoppers!" And Amazon does it anyway.

PS — To get our latest research on Amazon, anti-monopoly policy, and how communities can take charge of their local economies dropped in your inbox every 3 weeks, sign up: hometownadvantage.org

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

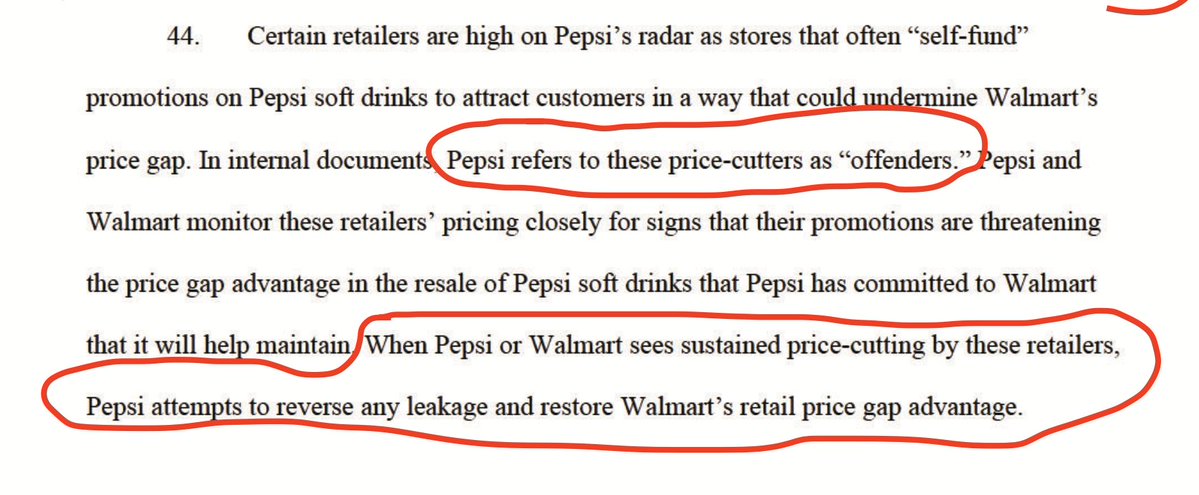

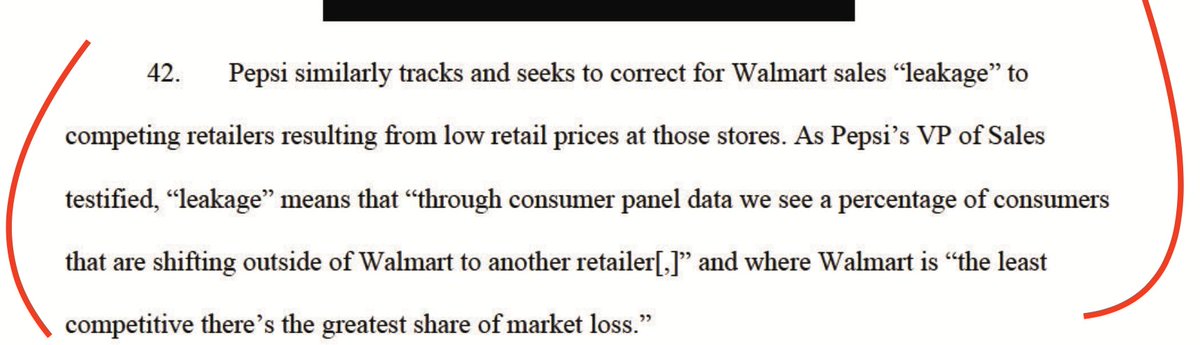

force a refresh