In recent days, I have seen many asking ‘how does Israel justify killing so many civilians to kill one man?’

I want to explain the concept of non-civilian cutoff values (NCVs) - essentially the number of civilians a military deems acceptable 'collateral damage' when striking.

I want to explain the concept of non-civilian cutoff values (NCVs) - essentially the number of civilians a military deems acceptable 'collateral damage' when striking.

Let me start with caveats. NCVs is an American term. There isn’t any public evidence the Israelis use the exact same system, Israeli war lawyers I have spoken say they aren't as explicit.

But their system is based on the US/UK one and so something similar likely exists.

But their system is based on the US/UK one and so something similar likely exists.

I'm also not a lawyer and am relying heavily on two brilliant books - The War Lawyers by Craig Jones @thewarspace (who fact checked this thread) and The Bodies in Person by Nick McDonell, plus conversations w @marcgarlasco and others.

I will screenshot relevant bits in the books

I will screenshot relevant bits in the books

Final caveat is that I am explaining, not justifying.

I am not saying whether any particular strike is legal or proportionate, but explaining how military lawyers (“JAGs” in the US system) decide if a strike that will kill civilians is within the realms of international law.

I am not saying whether any particular strike is legal or proportionate, but explaining how military lawyers (“JAGs” in the US system) decide if a strike that will kill civilians is within the realms of international law.

Targeting law is based on four key principles - necessity, distinction, proportionality and humanity.

If, as in the case of Jabalia, a military knows a strike on a military objective will kill civilians then the crucial legal term is proportionality.

If, as in the case of Jabalia, a military knows a strike on a military objective will kill civilians then the crucial legal term is proportionality.

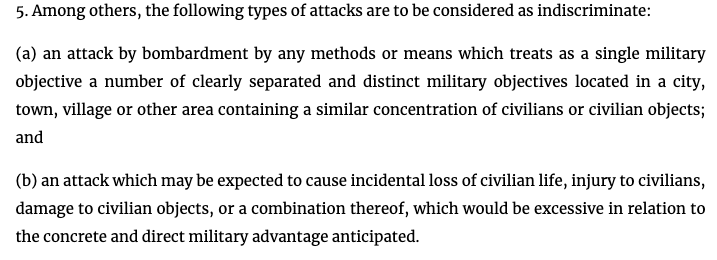

The Geneva Conventions, and specifically Article 51(5)(b) of Additional Protocol I, says a strike is indiscriminate or disproportionate if the impact on civilians is "excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated."

ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treatie…

ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treatie…

This is an inherently open question.

Excessive to who?

How do you weigh the life of civilians - including in many cases young children - against the military gain of killing a particular individual or hitting a particular site?

Excessive to who?

How do you weigh the life of civilians - including in many cases young children - against the military gain of killing a particular individual or hitting a particular site?

In the early 2000s, as America fought wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and drone campaigns in Pakistan, Yemen and elsewhere, this question grew.

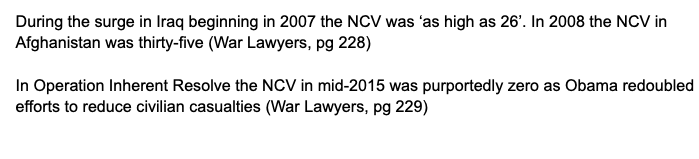

To 'quantify' this, lawyers under President Obama invented the concept of NCVs (though previous presidents had comparable mechanisms).

To 'quantify' this, lawyers under President Obama invented the concept of NCVs (though previous presidents had comparable mechanisms).

NCVs were not legal - they are a policy interpretation of international law. The idea being it would impose restrictions on civilian harm.

In practice over time it became a system by which the US military and its lawyers decided how many civilians was 'proportionate'.

In practice over time it became a system by which the US military and its lawyers decided how many civilians was 'proportionate'.

If a strike was expected to kill 8 civilians and the NCV was 10, it would go ahead.

Strikes with a higher than typical expected number of civilian deaths (NCV +1) were not absolutely prohibited, but they required specific permission from the US Secretary Defense and President.

Strikes with a higher than typical expected number of civilian deaths (NCV +1) were not absolutely prohibited, but they required specific permission from the US Secretary Defense and President.

This became the way in which advanced militaries - particularly the US but also others - decided whether a strike was 'proportionate'.

This is not to say they didn't try to prevent civilian harm in other ways (they did), but the NCV was a key factor.

This is not to say they didn't try to prevent civilian harm in other ways (they did), but the NCV was a key factor.

From the beginning critics said it was pretty arbitrary.

There was no fixed rule to what the 'number' was - it changed over time depending on the decisions of political and military leaders.

There was no fixed rule to what the 'number' was - it changed over time depending on the decisions of political and military leaders.

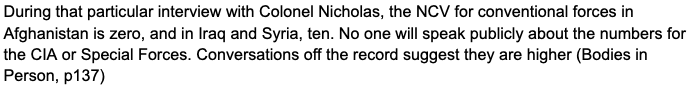

It was not even the same in different war zones at the same time.

At one point the Americans NCV allowed the killing of 10 civilians in a strike in Iraq and Syria, but none in Afghanistan.

At one point the Americans NCV allowed the killing of 10 civilians in a strike in Iraq and Syria, but none in Afghanistan.

Even within Coalitions, member nations apply different rules.

During the war against ISIS, for example, the Belgians were understood to have had a figure of 0 - meaning no strike took place if a civilian would be harmed.

The American figure, though classified, was far higher.

During the war against ISIS, for example, the Belgians were understood to have had a figure of 0 - meaning no strike took place if a civilian would be harmed.

The American figure, though classified, was far higher.

Now let's return to Israel.

Generally Israel - like the US - has 'looser' rules regarding civilian harm than other advanced militaries.

Generally Israel - like the US - has 'looser' rules regarding civilian harm than other advanced militaries.

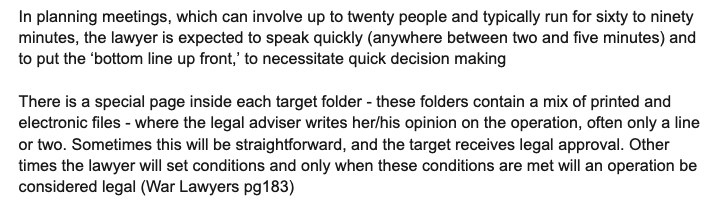

But each strike against large, non-dynamic targets will typically be signed off by a lawyer.

Jones outlines how they operate inside Israeli military meetings.

Jones outlines how they operate inside Israeli military meetings.

In Jabalia, a reasonable pre-strike assessment would have expected dozens, possibly hundreds, of civilians to be killed in a series of strikes on a heavily populated refugee camp.

So far we @airwars have tracked almost 100 civilians killed, with full research published next week

So far we @airwars have tracked almost 100 civilians killed, with full research published next week

Israel justified the strike as necessary to kill a senior Hamas operative, and other militants. See this intv with the IDF:

“This is the tragedy of war. We have been saying for days ‘move south, civilians that are not involved in Hamas move south.’

“This is the tragedy of war. We have been saying for days ‘move south, civilians that are not involved in Hamas move south.’

https://twitter.com/justinbaragona/status/1719412278351507487

This suggests that Israel sees its decision to tell one million Palestinians to flee to the south of the strip has some bearing on the civilian status of those who remain.

Most IHL lawyers would totally reject this.

Most IHL lawyers would totally reject this.

If this strike was signed off by Israeli military lawyers despite the expectation it would kill up to 100 civilians it indicates a major loosening of the rules of engagement.

In effect the NCV - or Israeli equivalent - has radically changed since Oct 7.

In effect the NCV - or Israeli equivalent - has radically changed since Oct 7.

https://twitter.com/MGLattimer/status/1720112321593258010

As quite rightly pointed out by @Lakhnaton, I wrote in the first tweet NCV stood for non-civilian cut off value when obviously it is non-combatant cut off value.

I did know that, honestly...

I did know that, honestly...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter