Blood and Iron, painted in 1914 by Charles Ernest Butler, perhaps sums up the way in which people across Europe initially thought about the war.

Here would be a heroic and fundamentally righteous conflict; everybody believed that God was on their side.

Here would be a heroic and fundamentally righteous conflict; everybody believed that God was on their side.

And, in verse, it is the much misunderstood Rupert Brooke who captured that old-fashioned spirit of noble conquest.

He was known as the "handsomest young man in England" and seemed to be the very best of the next generation.

Brooke died in 1915.

He was known as the "handsomest young man in England" and seemed to be the very best of the next generation.

Brooke died in 1915.

Things turned out different. Rather than the noble war that had been predicted, trenches were dug and winter set in.

The Kensingtons at Laventie by Eric Kennington (1915) shows WWI soldiers as they really were; not chivalrous knights, but men trying to keep out the bitter cold.

The Kensingtons at Laventie by Eric Kennington (1915) shows WWI soldiers as they really were; not chivalrous knights, but men trying to keep out the bitter cold.

And it became even worse.

The war which was supposed be over by Christmas dragged on; new weapons and cruel new ways of slaughtering were invented.

Gassed by John Singer Sargent (1919) shows the effect of chemical weapons on a group of soldiers — they are all blinded.

The war which was supposed be over by Christmas dragged on; new weapons and cruel new ways of slaughtering were invented.

Gassed by John Singer Sargent (1919) shows the effect of chemical weapons on a group of soldiers — they are all blinded.

And, of course, it is Wilfred Owen's famous poem which most vividly describes the experience of being gassed in the trenches.

Like many others, Owen had become totally disillusioned — an entire generation had been betrayed by "an old lie" and was suffering unimaginable evils.

Like many others, Owen had become totally disillusioned — an entire generation had been betrayed by "an old lie" and was suffering unimaginable evils.

There was also a home front; somebody had to make the weapons, plough the fields, keep things going — often it was women who stepped up to replace the men who had gone to fight.

In the Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal by George Clausen (1918) remembers those who stayed at home.

In the Gun Factory at Woolwich Arsenal by George Clausen (1918) remembers those who stayed at home.

But it was Edward Thomas, writing his poetry in the trenches, who most poignantly remembered those at home.

Simple, understated, devastating — unpicked flowers as a symbol of what was missing.

Simple, understated, devastating — unpicked flowers as a symbol of what was missing.

The long years of the Great War were also a time for satire and critique; everybody knew that Europe was self-imploding, but nobody could do anything about it.

This 1916 cartoon by Boardman Robinson summarises how many people felt about the war.

This 1916 cartoon by Boardman Robinson summarises how many people felt about the war.

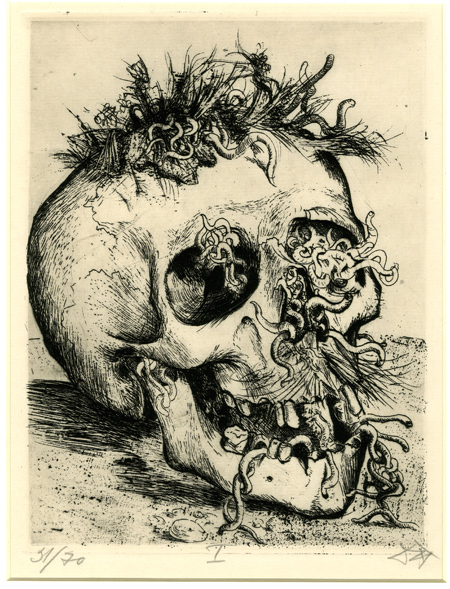

And it wasn't only satire or bitterness that came out of the war; it was madness too.

There's no coincidence that Surrealism as an art movement appeared after WWI — a generation betrayed turned inwards.

Apollinaire, who coined the term "Surrealism", did not survive it.

There's no coincidence that Surrealism as an art movement appeared after WWI — a generation betrayed turned inwards.

Apollinaire, who coined the term "Surrealism", did not survive it.

But perhaps nobody captured the sheer madness, the unabating nightmarish dread and inhuman horror of the war like Otto Dix — this is his War Triptych.

There had been terrible wars in the past, but nothing on this scale and nothing of this mechanised, industrial nature.

There had been terrible wars in the past, but nothing on this scale and nothing of this mechanised, industrial nature.

Dix, who fought in the war and survived it, created these etchings in the 1920s — the miseries of the fighting imprinted themselves on a whole generation.

Some things simply could not be forgotten.

Some things simply could not be forgotten.

And so the idea that this might be a glorious and noble war, that "God is on our side" and "the boys will be home by Christmas", was shattered.

Paths of Glory, painted by CRW Nevinson in 1917, epitomises that shift in perception.

*This* was the "glory" of the Great War...

Paths of Glory, painted by CRW Nevinson in 1917, epitomises that shift in perception.

*This* was the "glory" of the Great War...

And it wasn't only humans who suffered; nature was also ravaged by the bombs.

As in Zonnebeke by William Orpen (1918), forests and meadows became oceans of mud and blackened tree stumps, spotted with craters, trenches, and barbed war.

"What have we done?" they asked themselves.

As in Zonnebeke by William Orpen (1918), forests and meadows became oceans of mud and blackened tree stumps, spotted with craters, trenches, and barbed war.

"What have we done?" they asked themselves.

The poets and painters of the war thought of nature often. Some found in it a release from conflict — for the birds still sang every morning.

Others, like Carl Sandburg, looked forward to the day that nature would reclaim all that had been laid to waste.

Others, like Carl Sandburg, looked forward to the day that nature would reclaim all that had been laid to waste.

And that would happen eventually — the battlefields of the Western Front are now covered, as Sandburg said, with grass once again.

But that would have been hard to believe for soliders like those in Wyndham Lewis' Canadian Gun-pit (1919) — the fighting did not cease.

But that would have been hard to believe for soliders like those in Wyndham Lewis' Canadian Gun-pit (1919) — the fighting did not cease.

Not everybody took a purely negative, satirical, bitter view of the war.

There were those like W.N. Hodgson, who died in 1916 — he did not defend the war, but nor did he condemn it.

Hodgson merely reconciled himself to the fighting, and even found some good in it.

There were those like W.N. Hodgson, who died in 1916 — he did not defend the war, but nor did he condemn it.

Hodgson merely reconciled himself to the fighting, and even found some good in it.

Another was Alan Seeger, an American poet who fought with the French Foreign Legion and died at the Somme in 1916.

He, like Hodgson, found meaning in the suffering and in the fighting.

He, like Hodgson, found meaning in the suffering and in the fighting.

A war of such scale was bound to have long lasting and powerful consequences for the culture, politics, society, and economy of Europe.

But it also had a profound impact on people's mindset — a new world, as Paul Nash called one of his paintings, was emerging.

But it also had a profound impact on people's mindset — a new world, as Paul Nash called one of his paintings, was emerging.

And this "Great War", as it was once known, loomed large over society for decades.

As the grass and the trees returned, monuments to the dead were created.

Menin Gate at Midnight, painted by Will Longstaff in 1927, imagines the thousands of lost soldiers it memorialises.

As the grass and the trees returned, monuments to the dead were created.

Menin Gate at Midnight, painted by Will Longstaff in 1927, imagines the thousands of lost soldiers it memorialises.

But not everybody was happy with how the war was being remembered.

Siegfried Sassoon was disgusted by how the world seemed to have misunderstood the conflict, that the betrayal had not been rectified.

Here he is writing about the Menin Gate:

Siegfried Sassoon was disgusted by how the world seemed to have misunderstood the conflict, that the betrayal had not been rectified.

Here he is writing about the Menin Gate:

It's worth remembering that this has been a compilation of art and poetry from the Western Front alone, and largely from Britain.

But this conflict was global — there is much more out there, and these paintings and poems haven't even scratched the surface.

But this conflict was global — there is much more out there, and these paintings and poems haven't even scratched the surface.

The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge by Will Longstaff (1931) is among the most moving of post-war paintings.

WWII was bigger, but it was after "the Great War" that the world would, truly, never be the same again.

Peace came 105 years ago today, but the consequences are still being felt.

WWII was bigger, but it was after "the Great War" that the world would, truly, never be the same again.

Peace came 105 years ago today, but the consequences are still being felt.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh