There is no single version of The Thinker by Auguste Rodin.

There are at least 28 copies of it around the world, all of them slightly different, and all "original".

How? Well, here's a brief introduction to Rodin, the man who changed art forever...

There are at least 28 copies of it around the world, all of them slightly different, and all "original".

How? Well, here's a brief introduction to Rodin, the man who changed art forever...

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was by far the most important and influential sculptor of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

And, even more than that, he was regarded during his lifetime as the world's greatest living artist.

Why?

And, even more than that, he was regarded during his lifetime as the world's greatest living artist.

Why?

Well, Rodin was an unusual man. And his unusual style — of vigorously worked surfaces and seemingly unfinished sculptures — was initially met with skepticism, rejection, and even ridicule by the artistic establishment.

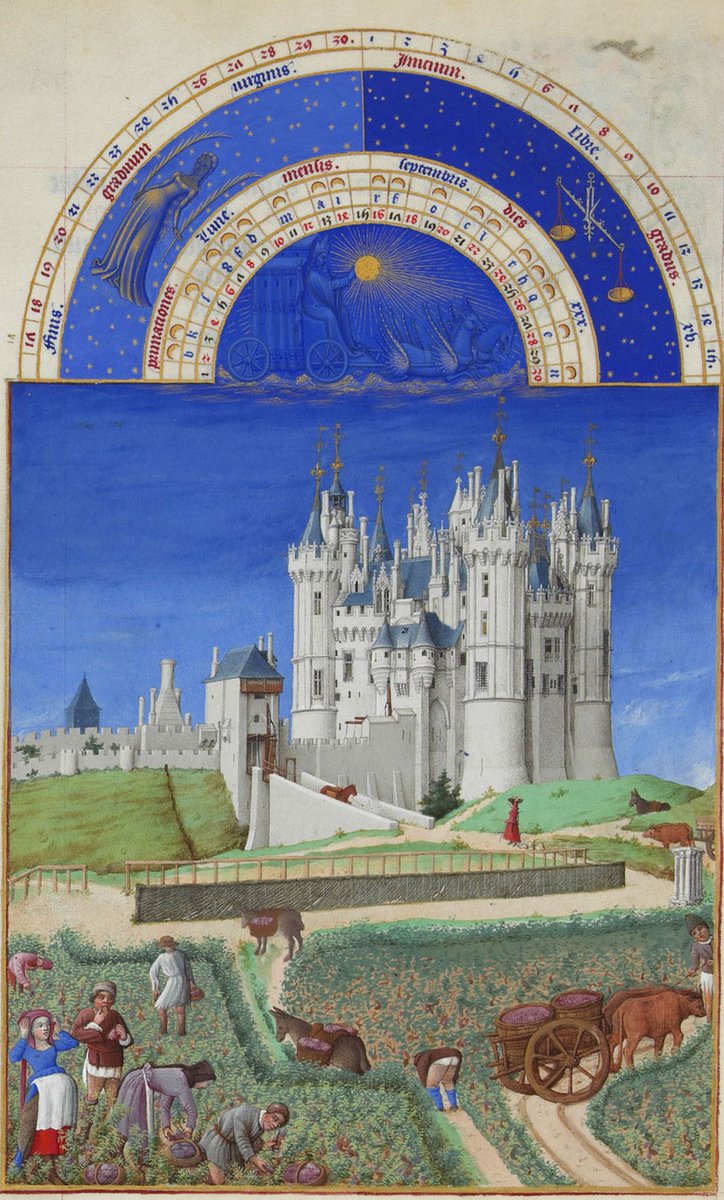

This was the sort of thing people were used to:

This was the sort of thing people were used to:

Just as shocking was that Rodin's statues rarely depicted a specific person or some figure from mythology, and nor were they allegorical.

His statues were, instead, about pure elements of the human condition.

It doesn't sound radical now; it was a revolution back then.

His statues were, instead, about pure elements of the human condition.

It doesn't sound radical now; it was a revolution back then.

And even when they depicted a specific person Rodin's sculptures were far removed from the sort of photographic realism and precise idealism of typical statues.

Nobody had ever dared to create something like this and call it a finished statue.

Nobody had ever dared to create something like this and call it a finished statue.

But that was Rodin.

He criticised the artistic establishment, accusing them of merely imitating the statues of Ancient Greece and Rome and of the Renaissance.

Rodin believed an artist should look to nature, not other artists, for their inspiration and — above all — truth:

He criticised the artistic establishment, accusing them of merely imitating the statues of Ancient Greece and Rome and of the Renaissance.

Rodin believed an artist should look to nature, not other artists, for their inspiration and — above all — truth:

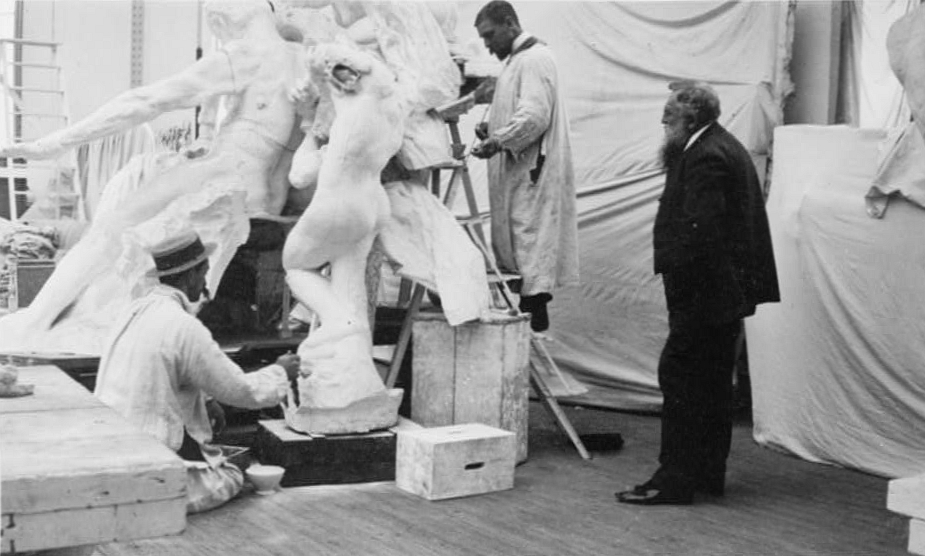

Rodin made small clay statues, working the material with his thumbs rapidly, while having the model move around naturally rather than staying still.

As the writer George Bernard Shaw later recalled about Rodin's methods:

As the writer George Bernard Shaw later recalled about Rodin's methods:

Plaster casts were made from these models by assistants in Rodin's workshop, and from those casts larger versions would be made in marble by those assistants or in bronze at specially contracted foundries.

Thus multiple different versions would be made of Rodin's works.

Thus multiple different versions would be made of Rodin's works.

David, sculpted by Michelangelo, exists in one place at one time — there is only one David.

The same is true of something like the Mona Lisa — there is only one.

Not so with Rodin's statues, which exist in several places at once, all slightly different, all equally "original".

The same is true of something like the Mona Lisa — there is only one.

Not so with Rodin's statues, which exist in several places at once, all slightly different, all equally "original".

So, what about The Thinker?

Rodin first created him in 1880 after being commissioned to create a set of bronze doors for the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris.

The museum never opened and Rodin kept working on the doors, called The Gates of Hell, until the end of his life.

Rodin first created him in 1880 after being commissioned to create a set of bronze doors for the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris.

The museum never opened and Rodin kept working on the doors, called The Gates of Hell, until the end of his life.

The Gates of Hell were inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy, and The Thinker — originally called The Poet — may have been inspired by him.

But this was not a statue of Dante; Rodin aimed at universality. Hence his statues were always unclothed; he wanted to capture eternal truths.

But this was not a statue of Dante; Rodin aimed at universality. Hence his statues were always unclothed; he wanted to capture eternal truths.

And this was, perhaps, Rodin's greatest achievement.

He liberated sculpture from cleaving blindly to "tradition" and "realism" and revitalised it with an urgent natural truthfulness and the soaring, gripping, unforgettable might of unshackled human emotion.

He liberated sculpture from cleaving blindly to "tradition" and "realism" and revitalised it with an urgent natural truthfulness and the soaring, gripping, unforgettable might of unshackled human emotion.

In this way Rodin evoked the forceful, almost barbarous, but somehow truthful and moving appearance of early Medieval sculpture.

It was imperfect and "unrealistic", but possessed greater emotional power than later works of overly precise, technically "accurate" sculpture.

It was imperfect and "unrealistic", but possessed greater emotional power than later works of overly precise, technically "accurate" sculpture.

What Rodin sought was the "inner truth" of humanity, not the mere photographic facts of outward appearance.

The Thinker was perhaps his masterpiece in this regard; it has rightly became a universal symbol for human intellect and emotional introspection.

The Thinker was perhaps his masterpiece in this regard; it has rightly became a universal symbol for human intellect and emotional introspection.

It was in 1904 that bronze casts based on the Poet from The Gates of Hell were first made — and The Thinker was born.

Now there are dozens of versions, all of different sizes and materials and made at different times, each of them thus unique in some way, whether major or minor.

Now there are dozens of versions, all of different sizes and materials and made at different times, each of them thus unique in some way, whether major or minor.

Rodin viewed sculpting as fundamentally sacred work. He once told the poet Rainer Maria Rilke that whenever he read prayers he would mentally replace the word "God" with "sculpture".

With an approach like that, no wonder his art seems to be bursting with life.

With an approach like that, no wonder his art seems to be bursting with life.

So this was a monumental personality and a revolutionary artist; so much of 20th century art was a direct consequence of Rodin's work.

For though he was met with resistance at first, by the end of his life Rodin was the undisputed Artist of the Age.

For though he was met with resistance at first, by the end of his life Rodin was the undisputed Artist of the Age.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter