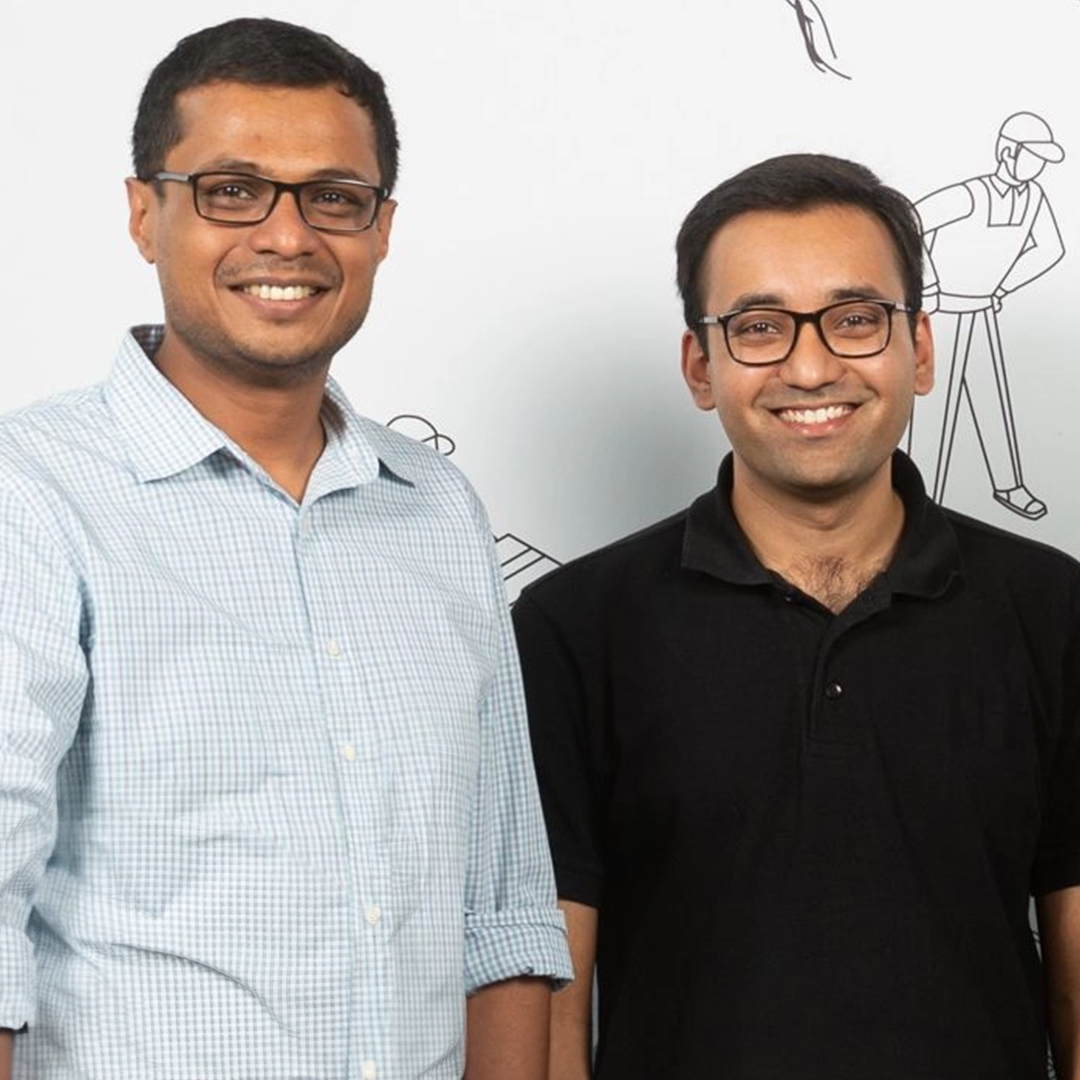

If you had visited the Robotics Lab at IIT Madras at night in 2013, there’s a good chance you would have tripped over Swapnil Jain or Tarun Mehta asleep on the floor. A decade later, both own beds and have defined India’s electric two wheeler industry. This is their story 🧵

2/45 Swapnil Jain came up with the name Ather Energy in 2009. Ather is a respelling of the classical element Aether, the purest form of energy. At the time, Swapnil was working on a unique project that he called the Famp, i.e. a fan powered by heat from oil lamps.

3/45 The Famp used a Stirling engine to convert thermal energy into power, with the goal of powering fans in remote Indian villages. Even though the Famp was discontinued, Swapnil’s desire to build an energy company persisted. Tarun Mehta joined him in his mission soon after.

4/45 They would end up spending the next three years building Stirling engines together in college, experimenting with different form factors and use cases. One of these engines leveraged solar power to generate energy, while another used the heat created by burning farm waste.

5/45 The duo even approached investors to try and finance productisation of their Stirling engines but with no business experience, no network, and no revenue, angels weren't enthused. Swapnil and Tarun’s dream of building an energy company was beginning to feel unattainable.

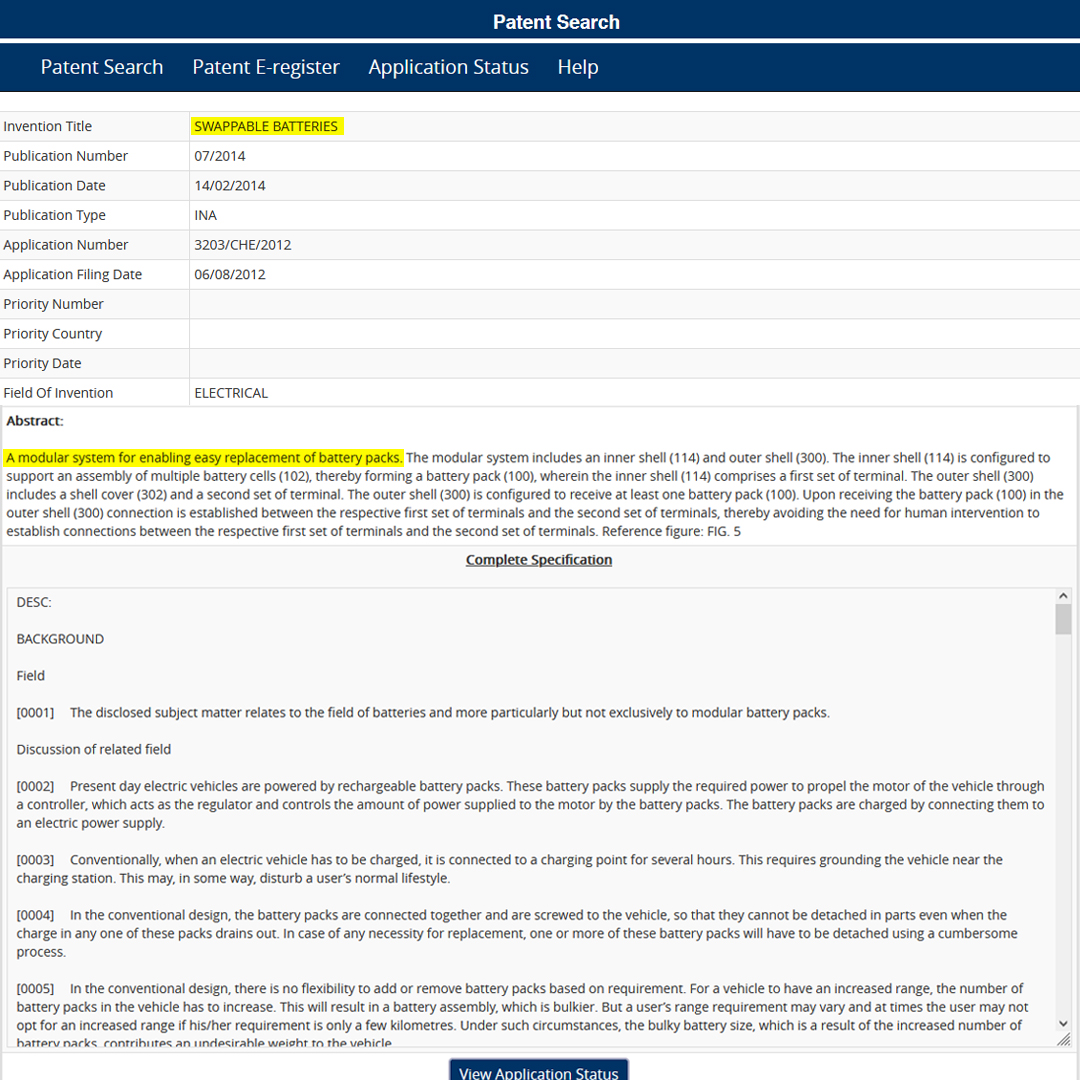

6/45 During their last semester at IIT though, Tarun discovered battery swapping. Mainstream swapping companies like Ample, BattSwap, and SUN Mobility didn’t exist in 2012, and Gogoro was in stealth. Tarun even filed a patent for a modular system to easily replace battery packs.

7/45 Before they could pursue battery swapping further, life got in the way of Swapnil and Tarun’s aspirations: not wanting to be left behind by their peers post graduation in 2012, they began working at General Motors and Ashok Leyland respectively.

8/45 They didn’t last long. After voicing their desire to continue working on Ather Energy, IIT Madras professors Krishna Kumar and Dr. Sandipan Bandhopadhyay invited them back, no strings attached. They returned to their alma mater in February of 2013.

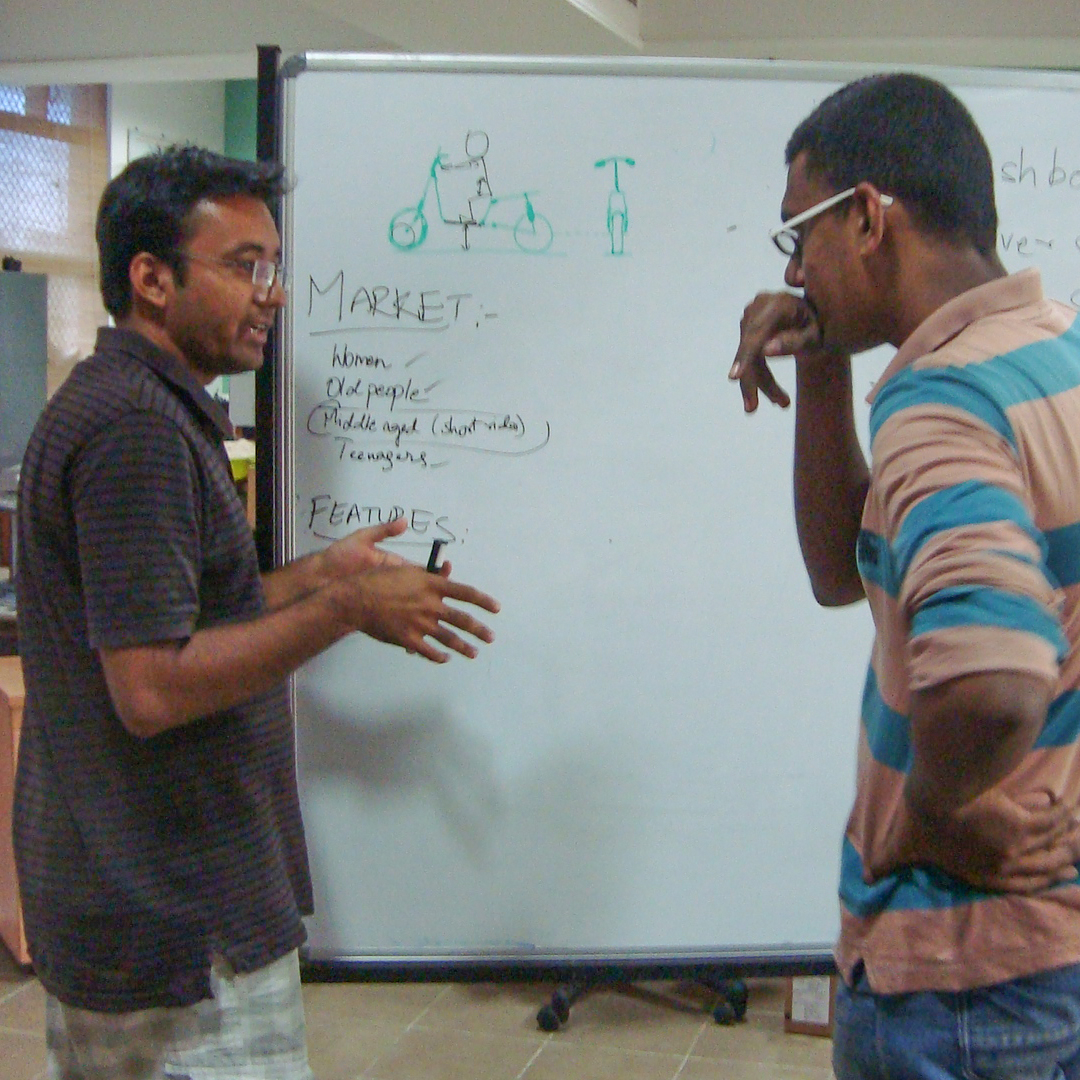

9/45 For the next six months, Swapnil and Tarun conducted market research. At first, they thought they would build a battery company, manufacturing lithium-ion batteries and selling them to EV owners who wanted to refurbish their ageing electric vehicles.

10/45 After talking to ~100 electric vehicle owners though, they realised that by and large, Indians hated their EVs. They were underpowered, unreliable, and ugly; why would anyone pay ₹40,000+ to upgrade the battery of an e-bike they wished they’d never bought?

11/45 It was at this point that Swapnil suggested something that would reroute the next decade of their lives: what if Ather Energy built an electric scooter that Indians actually wanted to buy? It had never been done before, but that didn’t mean it was impossible.

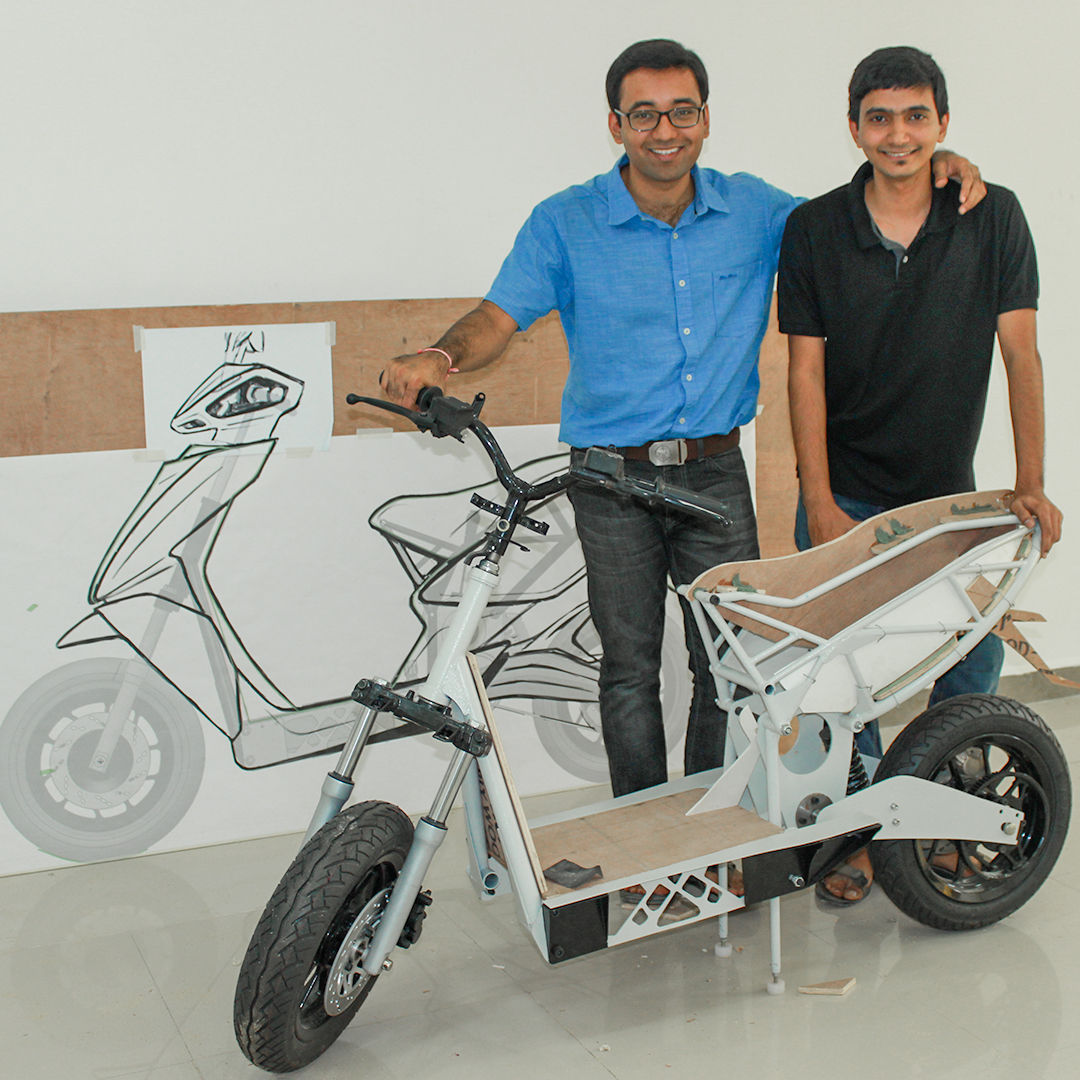

12/45 Swapnil and Tarun began this new quest by sizing up the competition; they tore down a YO EXL, noting the shape of its chassis, suspension strength, and basic dimensions. These measurements were then used to build a makeshift chassis for Ather’s first prototype EV.

13/45 By the first of May, 2015, they’d attached front and rear suspension, wheels, and handlebars to this chassis. It was a mishmash of a prototype, but it could roll, steer, and carry the weight of an ecstatic twentysomething engineer. In a word, it was remarkable.

14/45 By June they had completed a rudimentary battery pack, ensuring that they wouldn’t need to push their prototype around like a wheelbarrow anymore. This also marked the beginning of Ather’s journey of creating proprietary battery tech optimised for Indian conditions.

15/45 After wiring everything up and slapping a seat on top, Ather’s first electric scooter was ready to hit the roads of IIT Madras. From start to finish, building their first prototype had taken them four months. Also, notice the jugaad doorbell horn on the right handlebar.

16/45 Tarun shot pillion POV footage of Ather’s maiden journey, remarking that they had already overcome the sway issues faced by some Chinese e-bikes in the Indian market. Also, fun fact: this prototype was technically an electric cruiser due to a wheel configuration mistake.

17/45 This first prototype was largely financed by a ₹5 lakh research grant from IIT Madras. During this time, Ather Energy was also able to onboard its first employee, two interns, and two unpaid non-interns. They formally registered Ather Energy Pvt. Ltd. on October 21, 2013.

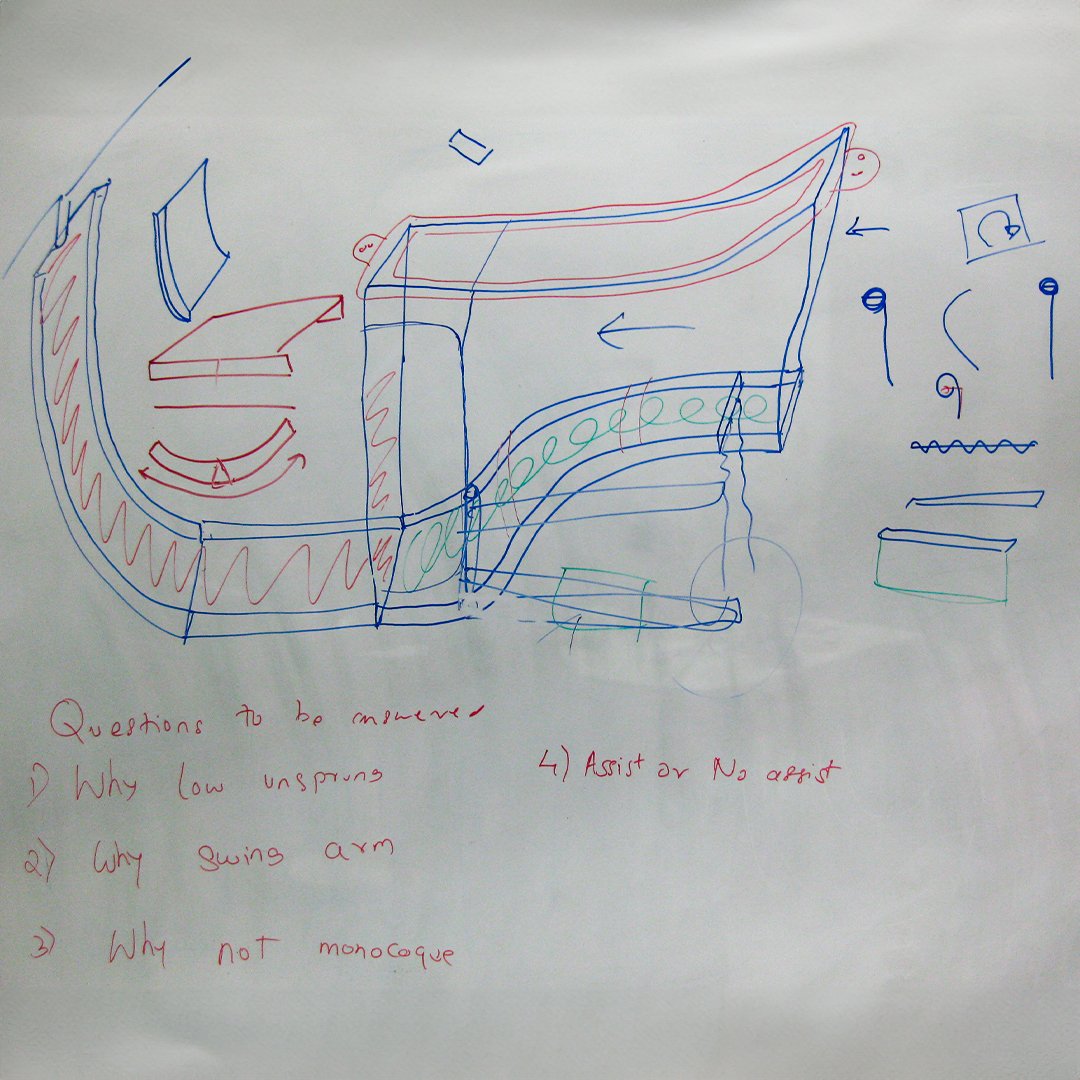

18/45 By November of 2013, progress on Ather’s second prototype was underway. Noteworthy changes include a horizontal battery housing and a bright orange cantilever swingarm with a rear mono suspension. To this day, Ather scooters use this rear fork and suspension combo.

19/45 This was also the first prototype to feature fairing. They didn’t know it then but Ather had beat Tesla to the punch with the Cybertruck aesthetic!

Ather was now one year into its startup journey and financially, things had begun to go south. The ₹5 lakh grant was spent.

Ather was now one year into its startup journey and financially, things had begun to go south. The ₹5 lakh grant was spent.

20/45 As a pre-revenue startup, investors weren’t interested in taking a risk on Ather. One VC even encouraged them to retrofit electric motors into Honda Activas. Out of options, Swapnil and Tarun raised a FFF round.

Also, it was around this time that Ather changed its logo.

Also, it was around this time that Ather changed its logo.

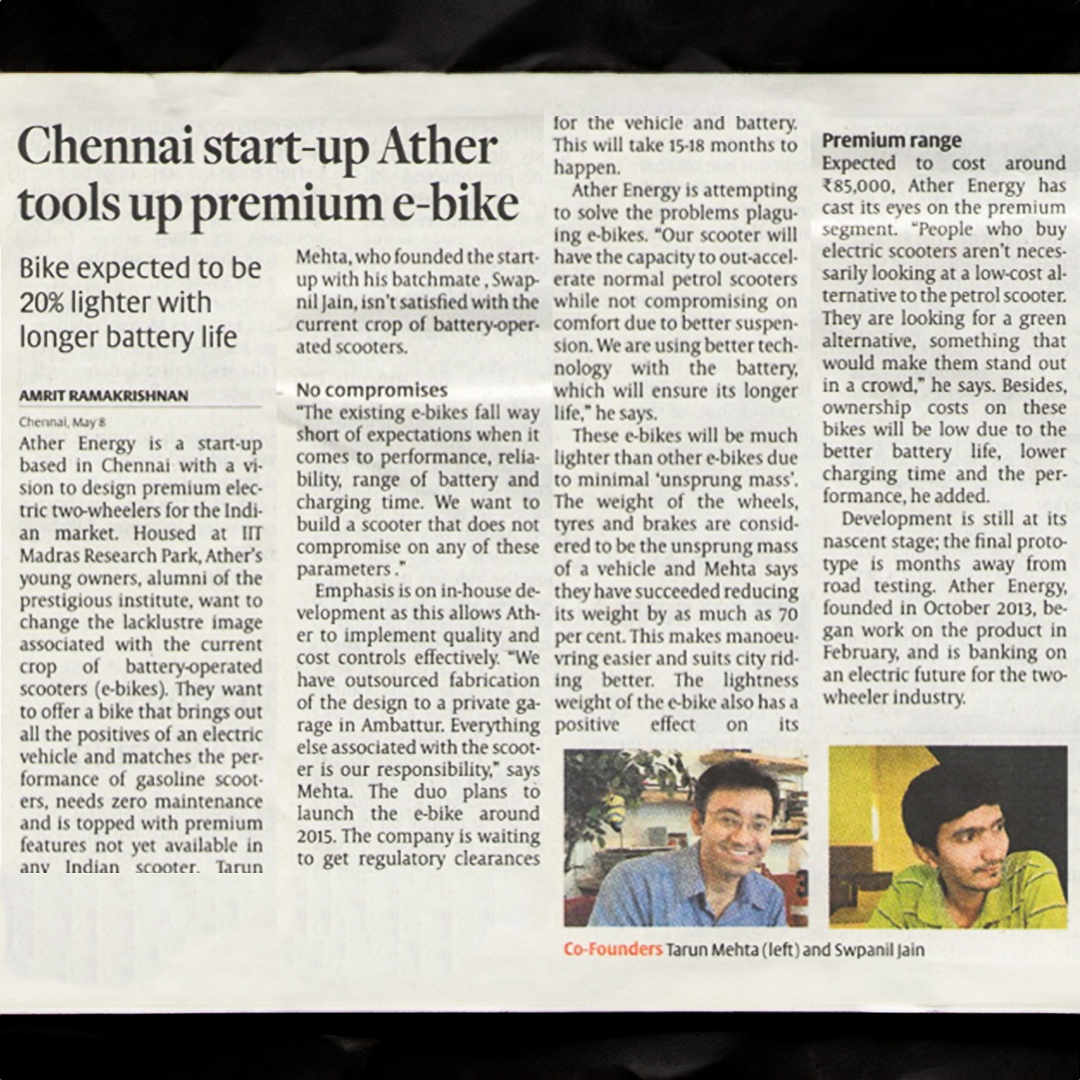

21/45 Instead of giving early backers a convertible note, Swapnil and Tarun took the crowdfunding approach, pre-selling 25 scooters for ₹85,000 each. They anticipated that they’d be able to start fulfilling these pre-orders by 2015.

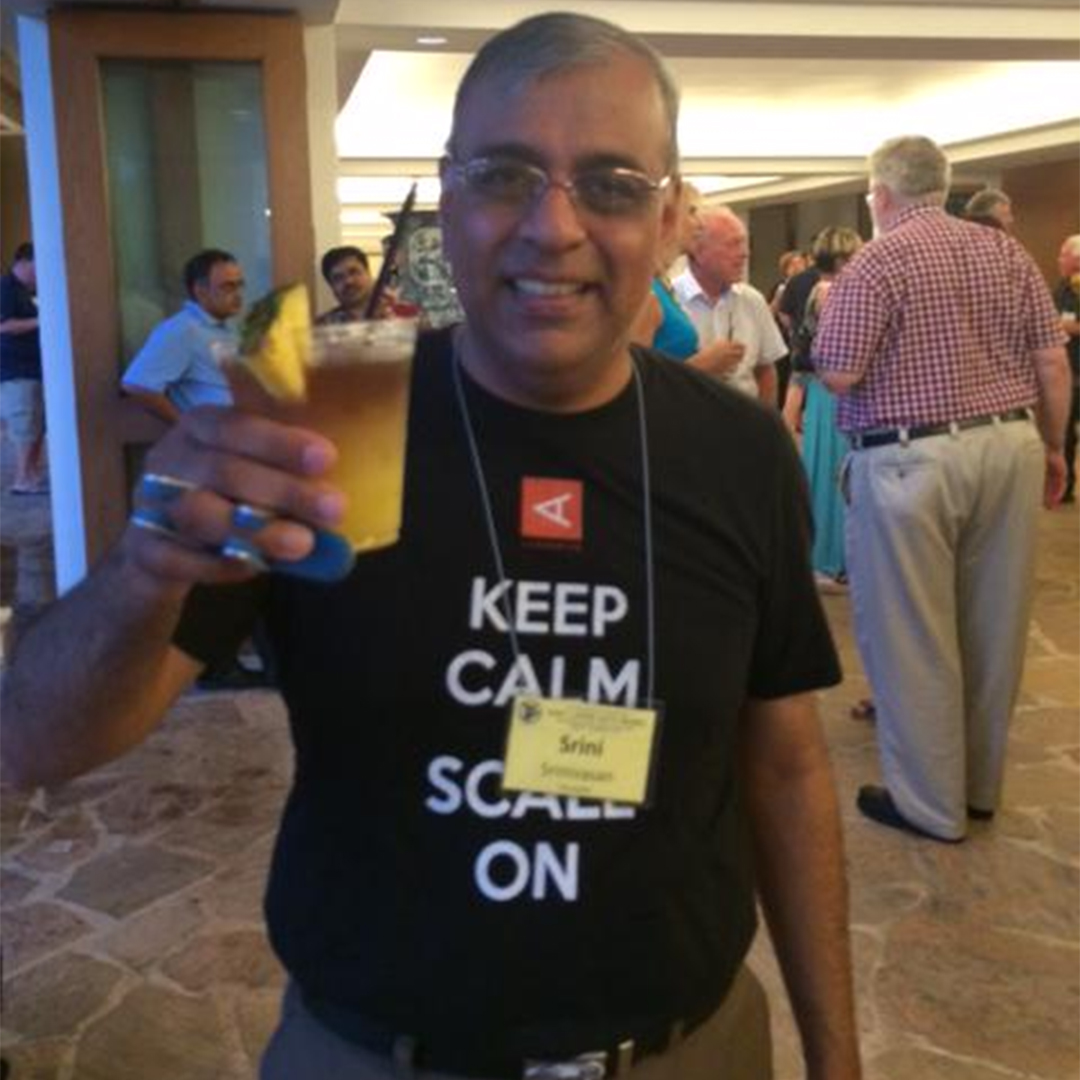

22/45 This early revenue impressed IIT Madras alumnus and entrepreneur Srini V. Srinivasan (@nasav). Srini was speaking on campus when Swapnil and Tarun approached him; he gave them ₹25 lakh, and the Government of India’s Technology Development Board invested ₹15 lakh.

23/45 This pre-seed capital enabled Ather to move into their first office space, Module 9, in IIT Madras’s Research Park. Soon after, in July of 2014, they also began work on their third and most ambitious prototype till date.

24/45 This prototype had a custom-built gearbox, two battery packs beneath the seat, and an Android tablet positioned between its handlebars. Ather would go on to become the first electric two wheeler company in the world to implement tablet-sized touch screen dashboards.

25/45 On a test drive, Tarun was able to break Ather’s speed record of 53 km/h, reaching 57 km/h. While driving, the tablet app showed him information like his battery charge and temperature, trip distance, and speed. Tragically, a button in the app replaced the doorbell horn.

26/45 If they were frugal, the ~₹45 lakh that Swapnil and Tarun had in the bank would last until October of 2014.

It didn’t. One of Ather’s employees was caught using pirated software in July, and because he was using it for Ather R&D, the startup was liable to pay damages.

It didn’t. One of Ather’s employees was caught using pirated software in July, and because he was using it for Ather R&D, the startup was liable to pay damages.

27/45 This was an embarrassing setback but to maintain momentum, Swapnil and Tarun borrowed money from their parents. They also dipped into the pre-order fund. This enabled the team of 12 to continue R&D while Swapnil and Tarun panic emailed investors.

28/45 Tarun had been in touch with a group of HNIs for the last six months, and was able to schedule a meeting with them on Lavelle Road in Bengaluru. He took a bus west from Chennai, hopeful that these angels would finance the next chapter of Ather’s journey.

They didn’t.

They didn’t.

29/45 A land deal had gone sideways for the HNIs, and they wouldn’t be able to fund Ather. Tarun was disappointed, but he decided to make the most of his time in Bengaluru and threw a Hail Mary by pitching to the co-founder of the biggest startup in the city.

30/45 Tarun’s visit to Flipkart’s Koramangala office couldn’t have happened at a better time. Sachin and Binny Bansal were on an angel spree, having just invested $1 million into MadRat Games 10 days prior, and so when he asked for ₹25 lakh, they gave him ₹6 crore instead.

31/45 After completing the skeleton of their fourth prototype, they announced this $1 million seed round in December of 2014. The news made headlines. This was the largest seed round of any indigenous Indian hardware startup, ever. Ather was in the spotlight.

32/45 By the end of the year, Ather had finished building their first clay model, and this important milestone in the company’s design process was covered by NDTV’s Gadget Guru. The startup was also in the process of shifting from Chennai to Bengaluru.

33/45 At first, the migration west was purely for Ather’s design team; they rented a bungalow in Indiranagar. As Swapnil and Tarun spent more time pitching to investors though, they realised that Bengaluru was the place to be for a rapidly growing hardware startup.

340/45 In the midst of this city transition, Ather was gearing up for the unveiling of the S340, which was scheduled for February of 2016 at Web Summit's first Indian technology conference SURGE. The startup was moving at warp speed to get the scooter done in time.

35/45 In May of 2015, Ather raised a $12 million Series A from Tiger Global. This was the capital they would use to make a full transition to Bengaluru and hire the people they needed to take the S340 over the finish line. The Indiranagar bungalow was beginning to get crowded.

36/45 By the time they had found a new home for their 40+ employees, SURGE was just six months away. They moved into the Star Avenue Building in Victoria Layout and began putting the finishing touches on the S340.

Pictured: Ather’s new design centre under renovation in 2015.

Pictured: Ather’s new design centre under renovation in 2015.

37/45 After three years of R&D, millions of dollars, and thousands of hours of hard work, Tarun finally showed the S340 to the world. Media coverage of the unveiling noted that Ather planned on commencing production of the S340 by the end of 2016. They didn’t even have a factory.

38/45 The next couple of years were difficult for Ather. Realising that the S340 couldn’t climb steep hills and couldn’t out-accelerate ICE scooters, they dropped the S and announced the 340 in June of 2018, alongside an even more powerful and more expensive scooter, the 450.

39/45 Pre-orders opened in June of 2018, and it was at this point that Ather began to realise that demand for the more powerful 450 was significantly higher than the 340. They would end up discontinuing the 340 in September of 2019.

40/45 On September 11, 2018, Ather handed out the first 450s to customers. It had been nearly six and a half years since Swapnil and Tarun quit their jobs to build an EV company, and nine years since Ather Energy got its name.

41/45 Today, Ather is the fourth-largest electric two wheeler company in India by monthly sales. They’ve set up 1,400+ fast chargers across the country, their scooters have driven a total of 1 billion kilometres, and they average a million rides per day.

42/45 Young people who never would have dreamed of launching their own hardware startup in India can now look to Swapnil and Tarun’s story for courage and inspiration. Ather even has a startup mafia of former employees who have gone on to launch hardware ventures of their own.

43/45 Looking to the future, Ather’s core mission is to reduce the cost of electricity. This is why they haven’t dropped the word Energy in their name. Electric scooters will likely remain their focus for the next decade but beyond that, there’s no telling what Ather might do.

44/45 If you enjoyed this thread, you’ll love my podcast episode with Tarun Mehta. We discussed Ather’s entry into Nepal, India’s role in the global electric two wheeler industry, and the realities of building hardware in India. You can find a link to the pod in my bio.

450/45 Also, if researching and writing about Indian startups is something that interests you, we’re hiring at Backstage with Millionaires! DM me and I’ll share a link to our job application form.

Thanks for letting me tell your story @tarunsmehta and @swapniljain89 🙏

Thanks for letting me tell your story @tarunsmehta and @swapniljain89 🙏

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter