One of the coolest concepts in urban design is "Architecture of the Night".

It's about how we illuminate our cities and buildings and streets.

And though it originated in 1920s New York, in 2023 the Architecture of the Night is more important than ever...

It's about how we illuminate our cities and buildings and streets.

And though it originated in 1920s New York, in 2023 the Architecture of the Night is more important than ever...

The concept of "Architecture of the Night", or "Nocturnal Architecture", first appeared in the 1920s.

Although we've been lighting our cities for centuries, it was with the invention of powerful electric lights that a new sort of nocturnal urban landscape became possible.

Although we've been lighting our cities for centuries, it was with the invention of powerful electric lights that a new sort of nocturnal urban landscape became possible.

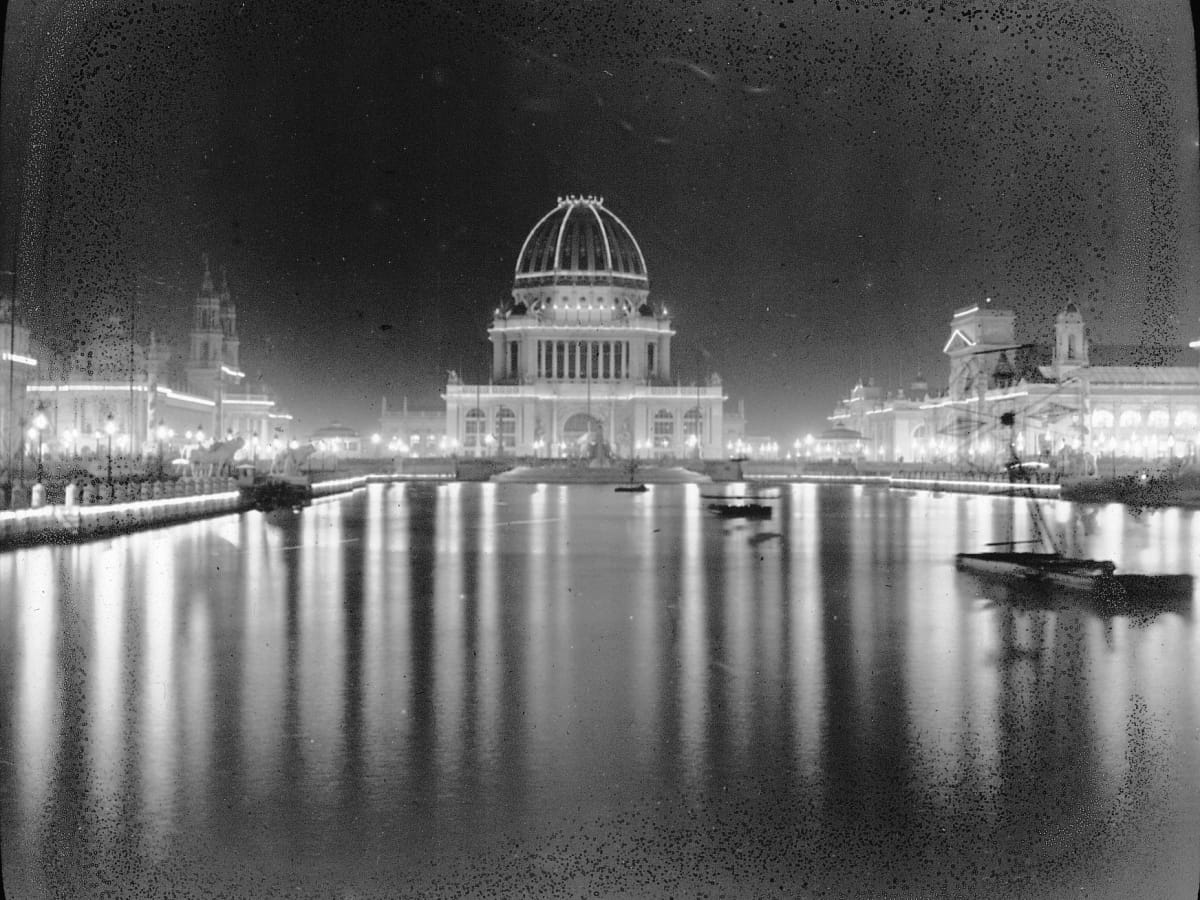

The first experiments came in the late 19th century with the World's Fairs, particularly in Paris in 1889 and Chicago in 1893.

Consider the Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle — then the world's tallest building by far — rigged up with spotlights:

Consider the Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle — then the world's tallest building by far — rigged up with spotlights:

Nobody had ever seen anything like that before — the days of candles and gas lamps were over; the Age of Electricity was about to begin.

In Chicago, four years later, the experiments with electrical lighting were turned up a notch:

In Chicago, four years later, the experiments with electrical lighting were turned up a notch:

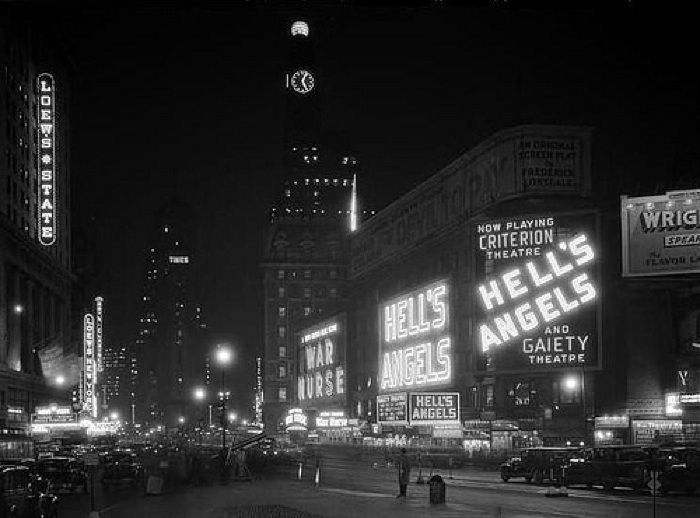

By the 1920s the importance of light had become obvious — not only for lighting buildings and streets but also in advertising.

For people who had lived through the change it's hard to imagine just how much *brighter* cities had become.

Consider New York's Times Square:

For people who had lived through the change it's hard to imagine just how much *brighter* cities had become.

Consider New York's Times Square:

But not everybody thought electric illumination was being used properly. As one critic said of London's Piccadilly Circus:

"This is hideous and discordant... no architectural scheme runs through the electric signs."

"This is hideous and discordant... no architectural scheme runs through the electric signs."

Thus architects, designers, and urban planners started thinking more carefully about how to use lighting.

In 1929 Gordon Selfridge even said "light is as necessary to architectural production today as was colour to the painter."

In 1929 Gordon Selfridge even said "light is as necessary to architectural production today as was colour to the painter."

And it was the American Art Deco architect Raymond Hood, who designed the Rockefeller Center and the American Radiator Building, who seems to have first coined the term "Architecture of the Night".

Hood considered it a new art form which had barely got going.

Hood considered it a new art form which had barely got going.

And if we look at Raymond Hood's Rockefeller Center we can see just how seriously he had approached its illumination.

This is far from the "discordant" Piccadilly Circus; here we have lighting carefully curated to enhance the sheer scale, the lofty drama, the soaring lines.

This is far from the "discordant" Piccadilly Circus; here we have lighting carefully curated to enhance the sheer scale, the lofty drama, the soaring lines.

Architects like Hood realised that lighting wasn't arbitrary — used properly it could enhance the design of a building and improve the appearance of a city overall.

Or, used carelessly, electric lighting could turn cities into aesthetic and psychological hellscapes of confusion.

Or, used carelessly, electric lighting could turn cities into aesthetic and psychological hellscapes of confusion.

The Chrysler Building represents the pinnacle of the first age of Noctural Architecture, with a lighting scheme designed by William Di Giacomo and Steve Negrin.

Nearly a century later it still fires the imagination with the interplay of light & shadow so typical of Art Deco.

Nearly a century later it still fires the imagination with the interplay of light & shadow so typical of Art Deco.

Urban growth slowed during the 1940s, before exploding into life again after the Second World War and continuing breathlessly through to today.

Lighting has also developed dramatically, and so the Architecture of the Night has entered another Age.

Just look at Kuala Lumpur:

Lighting has also developed dramatically, and so the Architecture of the Night has entered another Age.

Just look at Kuala Lumpur:

Or consider the Sky Beam installed atop the Luxor Las Vegas Hotel in 1993; this is the world's single most powerful light.

It can be seen from nearly 300 miles away.

Raymond Hood's prediction that Architecture of the Night was barely getting started has proven true.

It can be seen from nearly 300 miles away.

Raymond Hood's prediction that Architecture of the Night was barely getting started has proven true.

The whole concept of Nocturnal Architecture rests on the simple fact that lighting causes both buildings and entire cities to look completely different at night.

Consider Singapore's Gardens by the Bay.

During the day a strange metal structure; by night a technicolour fantasy.

Consider Singapore's Gardens by the Bay.

During the day a strange metal structure; by night a technicolour fantasy.

There's a peculiar way in which our modern Architecture of the Night — which is all about colour — harks back to the stained glass windows of Medieval Cathedrals.

A purity of form: colour and light are elemental forces, and thus more direct than any other form of art.

A purity of form: colour and light are elemental forces, and thus more direct than any other form of art.

And there's important science to this: lighting has a colossal impact on our psychology, health, and behaviour.

After all, we evolved according to the sun and the day-night cycle.

Thus Noctural Architecture isn't only about aesthetics; it is also about public health.

After all, we evolved according to the sun and the day-night cycle.

Thus Noctural Architecture isn't only about aesthetics; it is also about public health.

And the Architecture of the Night isn't only about new buildings; it has also allowed us to illuminate older buildings in ways never before possible.

Cathedrals, already awe-inspiring, have only been enhanced by the great swathes of light now cast upon them.

Cathedrals, already awe-inspiring, have only been enhanced by the great swathes of light now cast upon them.

And nor is it only about skyscrapers.

The Architecture of the Night is about *everything* we build, from roads to football stadiums.

Like the Allianz Arena in Munich, home of FC Bayern, which lights up in different colours:

The Architecture of the Night is about *everything* we build, from roads to football stadiums.

Like the Allianz Arena in Munich, home of FC Bayern, which lights up in different colours:

And the Architecture of the Night is more important than ever.

Our urban environments are expanding rapidly and, wherever you have a town or city, you *need* lighting.

Why shouldn't we think about our lighting more carefully, then?

Our urban environments are expanding rapidly and, wherever you have a town or city, you *need* lighting.

Why shouldn't we think about our lighting more carefully, then?

As Raymond Hood realised a century ago, lighting is an art form of its own, with immense aesthetic and artistic potential to enhance our urban environments.

Not to mention the psychology of light, which can make us happy or depressed, energised or tired, comfortable or confused.

Not to mention the psychology of light, which can make us happy or depressed, energised or tired, comfortable or confused.

And that is the Architecture of the Night.

Technology has realised Hood's dream; the possibilities for turning our cities into carefully curated kaleidoscopes of light and colour, of illumination and shadow, are nearly endless.

Time for the Architects of the Night to rise.

Technology has realised Hood's dream; the possibilities for turning our cities into carefully curated kaleidoscopes of light and colour, of illumination and shadow, are nearly endless.

Time for the Architects of the Night to rise.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh