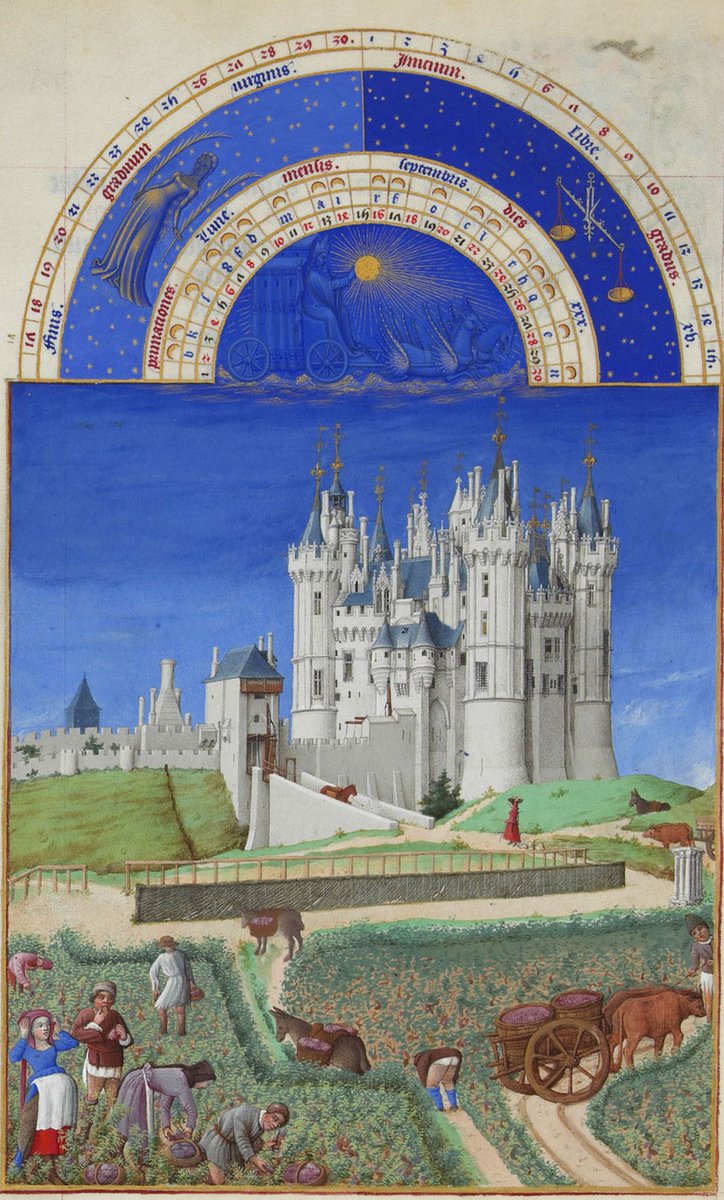

International Gothic (1350-1450)

The late flowering of Medieval art. Little concern for "realism" — hundreds of figures crammed into impossible spaces, abundant details, strange castles, and lots of flowers.

The final days of chivalry in art.

The late flowering of Medieval art. Little concern for "realism" — hundreds of figures crammed into impossible spaces, abundant details, strange castles, and lots of flowers.

The final days of chivalry in art.

Early Renaissance (1425-1490)

Italian painters, inspired by the classical art of Ancient Greece and Rome, were getting to grips with realistic perspective, human form, and natural lighting.

But things were still fairly stylised — a leftover of the Gothic.

Italian painters, inspired by the classical art of Ancient Greece and Rome, were getting to grips with realistic perspective, human form, and natural lighting.

But things were still fairly stylised — a leftover of the Gothic.

High Renaissance (1490-1530)

The brief consummation of the Italian Renaissance.

Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo — this famous triumvirate dominates an era of naturalistic, idealised, and harmonious art.

Mellow colours, smooth brushwork, and emphasis on the human form.

The brief consummation of the Italian Renaissance.

Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo — this famous triumvirate dominates an era of naturalistic, idealised, and harmonious art.

Mellow colours, smooth brushwork, and emphasis on the human form.

Netherlandish Renaissance (1420-1570)

Concurrent with the Italian Renaissance was a similar revolution in Northern European art, particularly in the Netherlands.

They were masters of highly detailed, almost photorealistic oil paintings and of the fantastically bizarre.

Concurrent with the Italian Renaissance was a similar revolution in Northern European art, particularly in the Netherlands.

They were masters of highly detailed, almost photorealistic oil paintings and of the fantastically bizarre.

Mannerism (1530-1600)

A peculiar time for European art which has generated much controversy. It was, perhaps, all about finding a new direction for art after the great heights of the Renaissance.

Experimental, artificial, peculiar — as in Giuseppe Arcimbolo's portraits.

A peculiar time for European art which has generated much controversy. It was, perhaps, all about finding a new direction for art after the great heights of the Renaissance.

Experimental, artificial, peculiar — as in Giuseppe Arcimbolo's portraits.

Baroque (1600-1750)

An era so broad it can hardly be described properly.

Though, from the gruesome and shadowy art of Caravaggio to the bombastic and colourful classical paintings of Rubens, the Baroque was, generally, an age of intense drama in art.

An era so broad it can hardly be described properly.

Though, from the gruesome and shadowy art of Caravaggio to the bombastic and colourful classical paintings of Rubens, the Baroque was, generally, an age of intense drama in art.

Then again, just as Caravaggio and Rubens are called Baroque despite their immense differences, so too is somebody like the French landscapist Claude Lorrain.

Landscapes like these, idealised and highly classicising, were finally becoming a serious genre.

Landscapes like these, idealised and highly classicising, were finally becoming a serious genre.

Rococo (1730-1780)

A frivolous evolution of the Baroque which was intimately tied up with European high society before the revolutions of the 19th century.

Theatrical and fanciful, best captured by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in Italy and Fragonard or Watteau in France.

A frivolous evolution of the Baroque which was intimately tied up with European high society before the revolutions of the 19th century.

Theatrical and fanciful, best captured by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in Italy and Fragonard or Watteau in France.

Neoclassicism (1780-1815)

An artistic reaction against the frivolities of Rococo; painters and thinkers turned to Ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration.

Austere, bold, statuesque — this was the style of the French Revolutionaries, most of all Jacques-Louis David.

An artistic reaction against the frivolities of Rococo; painters and thinkers turned to Ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration.

Austere, bold, statuesque — this was the style of the French Revolutionaries, most of all Jacques-Louis David.

Romanticism (1790-1850s)

A reaction against the Enlightenment and the Age of Science.

Romanticism was about the power, beauty, and mystery of nature, and the depths of the human soul and of our emotions.

The art of the sublime — whatever, precisely, that was.

A reaction against the Enlightenment and the Age of Science.

Romanticism was about the power, beauty, and mystery of nature, and the depths of the human soul and of our emotions.

The art of the sublime — whatever, precisely, that was.

Pre-Raphaelitism (1848-1900)

A peculiar British movement which aimed to recapture the truthfulness, love of nature, bright colours, and vigour of Medieval art.

The original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood disbanded quickly, but they influenced Victorian Art for decades.

A peculiar British movement which aimed to recapture the truthfulness, love of nature, bright colours, and vigour of Medieval art.

The original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood disbanded quickly, but they influenced Victorian Art for decades.

Academicism (1815-1900)

This was the style of the cultural establishment in 19th century Europe, as taught in the Academies and promoted in exhibitions.

Inspired by the Renaissance, usually idealised, and all about scenes from mythology or history.

This was the style of the cultural establishment in 19th century Europe, as taught in the Academies and promoted in exhibitions.

Inspired by the Renaissance, usually idealised, and all about scenes from mythology or history.

Realism (1840s-1900)

A rebellion against the art of the Academies.

Painters like Jean-Francois Millet and Gustave Courbet went into the world and painted ordinary scenes.

They wanted to depict the unidealised world as it really was: sweat, blood, mud, and tears.

A rebellion against the art of the Academies.

Painters like Jean-Francois Millet and Gustave Courbet went into the world and painted ordinary scenes.

They wanted to depict the unidealised world as it really was: sweat, blood, mud, and tears.

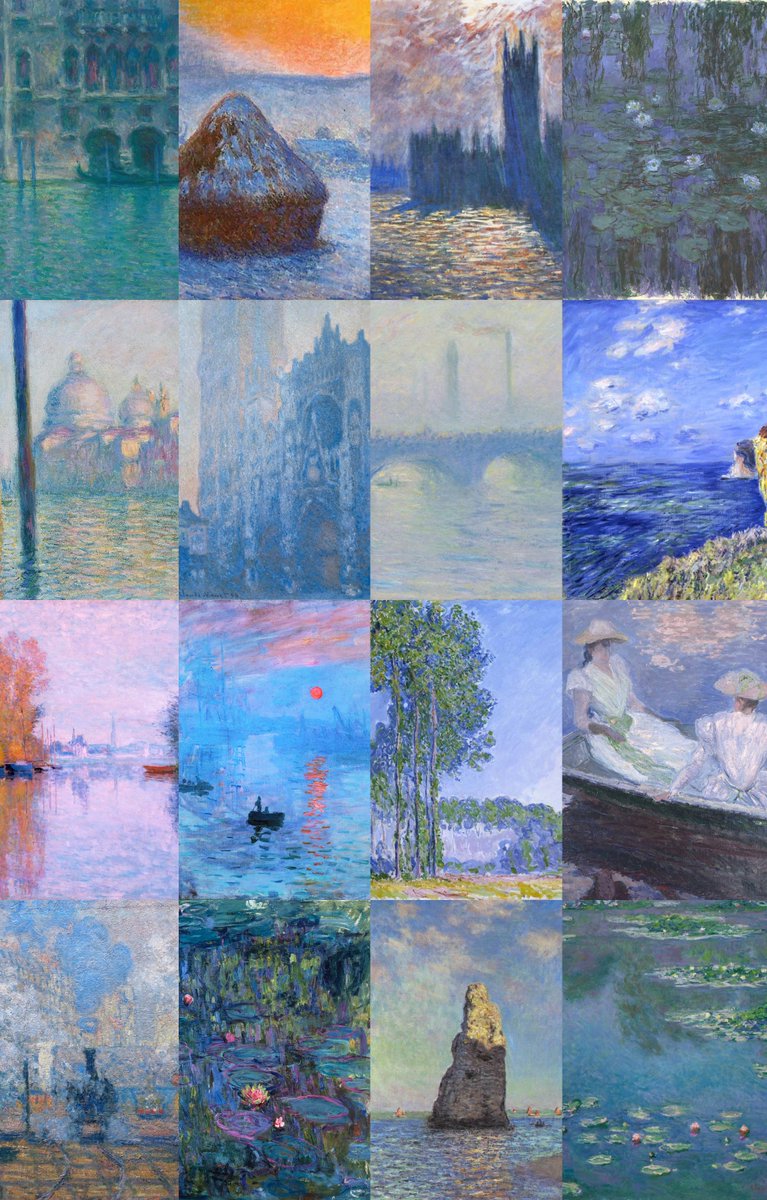

Impressionism (1871-1926)

The movement that changed the world, led by Monet and Manet.

They wanted to find a more realistic way of painting reality than Academicism, which it rebelled against.

Fundamentally, Impressionism is about the effects of light on the world around us.

The movement that changed the world, led by Monet and Manet.

They wanted to find a more realistic way of painting reality than Academicism, which it rebelled against.

Fundamentally, Impressionism is about the effects of light on the world around us.

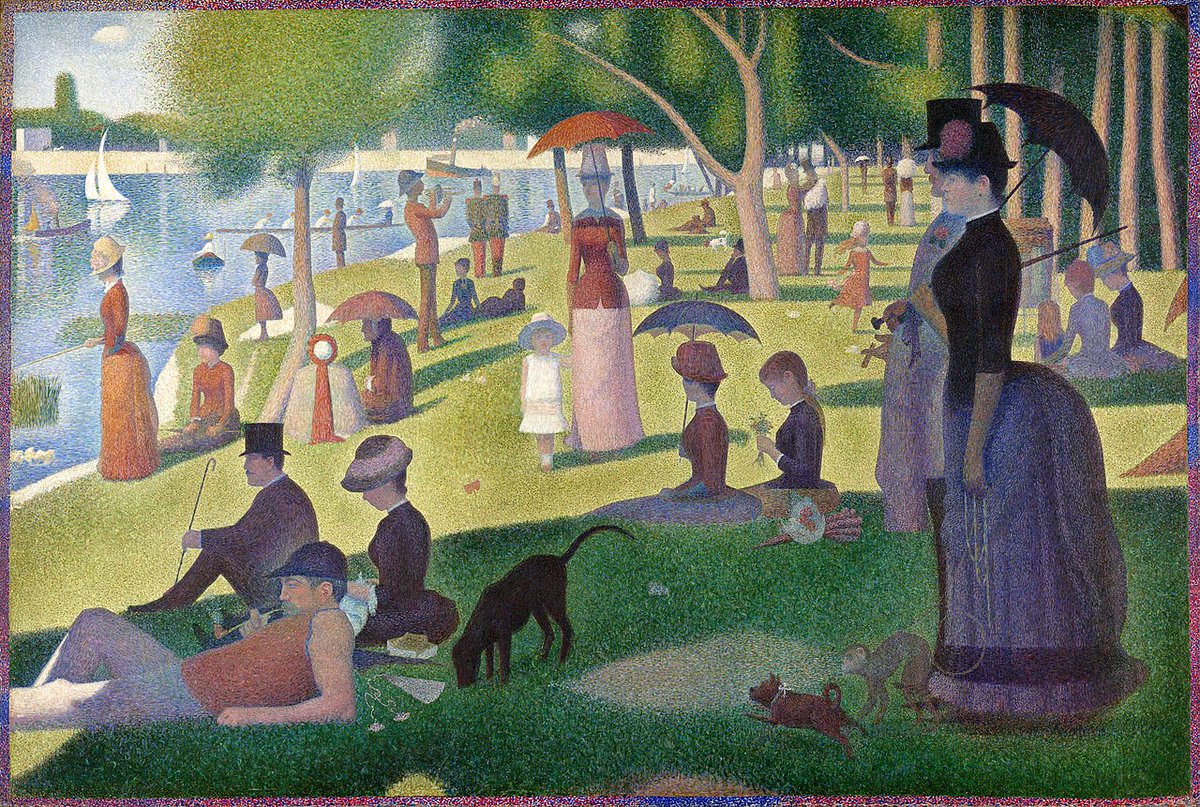

Pointillism (1884-1925)

A movement founded by one man, Georges Seurat, and continued by his pupil, Paul Signac.

Inspired by new science regarding human eyesight and optics, they made paintings out of thousands of tiny, individual dots of colour.

A movement founded by one man, Georges Seurat, and continued by his pupil, Paul Signac.

Inspired by new science regarding human eyesight and optics, they made paintings out of thousands of tiny, individual dots of colour.

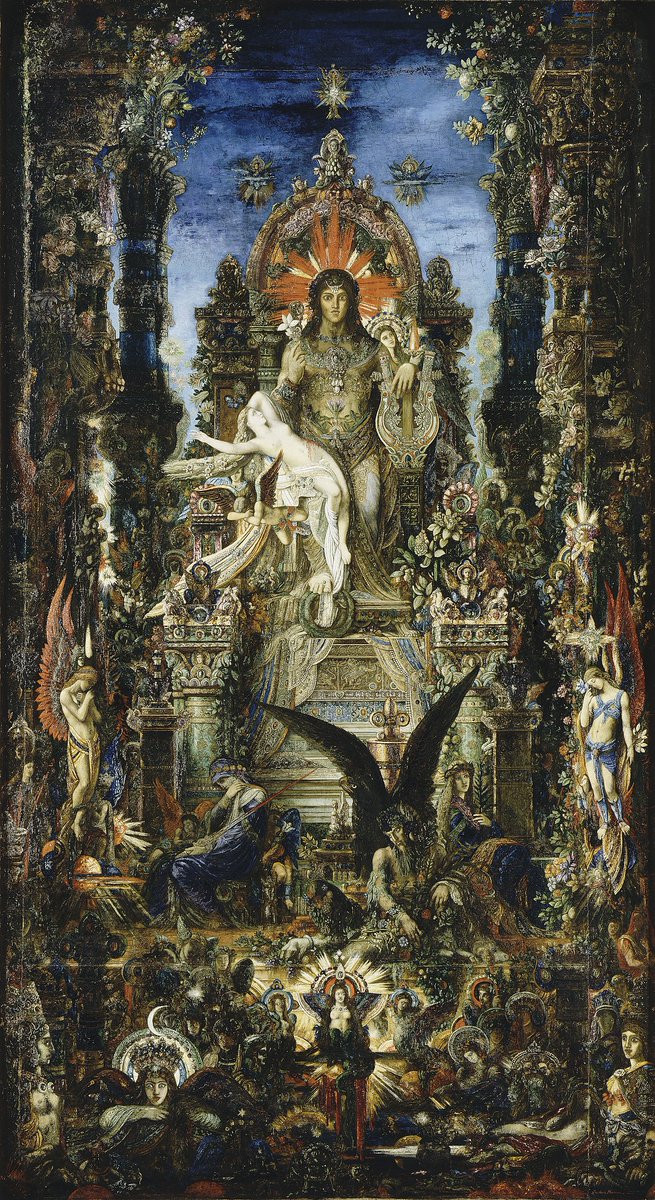

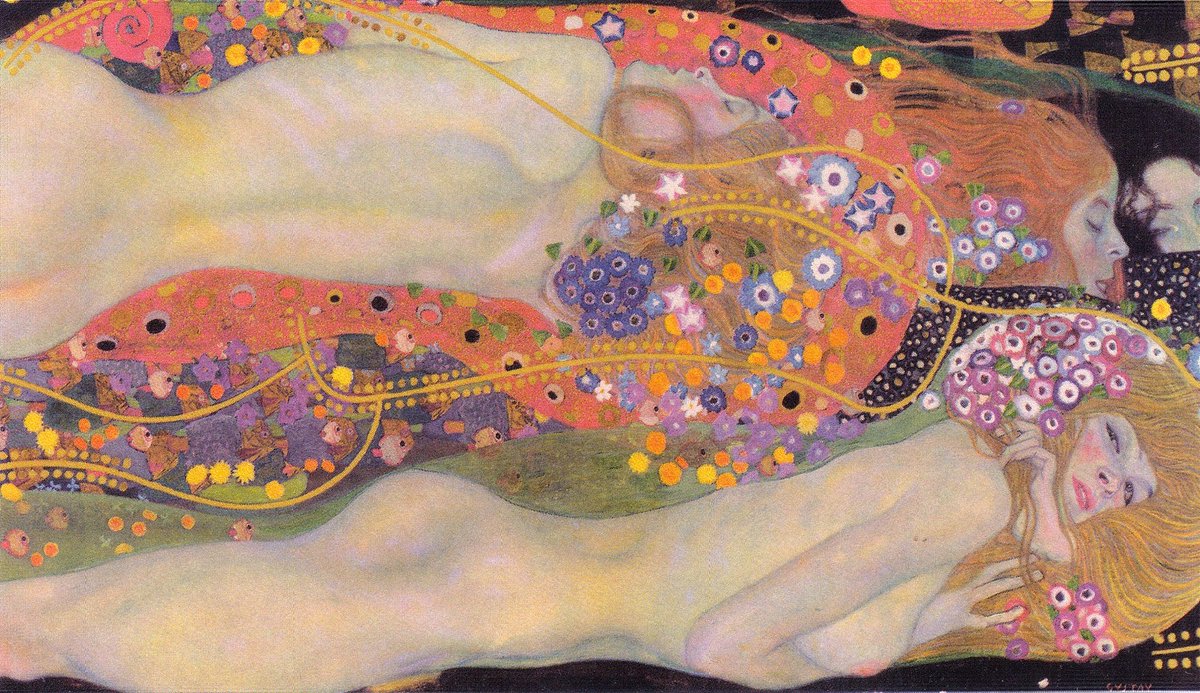

Symbolism (1857-1914)

A strange late 19th century European art movement which saw artists retreat inwards.

This is still "realistic" art, but it is filled with obscure imagery and mysterious scenes, often dark and fantastical.

Think of Moreau, Malczewski, Böcklin, and Klimt.

A strange late 19th century European art movement which saw artists retreat inwards.

This is still "realistic" art, but it is filled with obscure imagery and mysterious scenes, often dark and fantastical.

Think of Moreau, Malczewski, Böcklin, and Klimt.

Cubism (1907-1920s)

As the name suggests, this movement — founded by Picasso — was all about transforming the world as we perceive it into a different reality: one of geometry.

It was partly inspired by the way cameras could capture an object from many different angles.

As the name suggests, this movement — founded by Picasso — was all about transforming the world as we perceive it into a different reality: one of geometry.

It was partly inspired by the way cameras could capture an object from many different angles.

Art Deco (1920-1935)

Art Deco is most often associated with architecture and interior design: sharp geometry, dramatic lighting, shiny surfaces, and an atmosphere which still feels futuristic over a century later.

Tamara de Lempicka was probably the ultimate Art Deco painter.

Art Deco is most often associated with architecture and interior design: sharp geometry, dramatic lighting, shiny surfaces, and an atmosphere which still feels futuristic over a century later.

Tamara de Lempicka was probably the ultimate Art Deco painter.

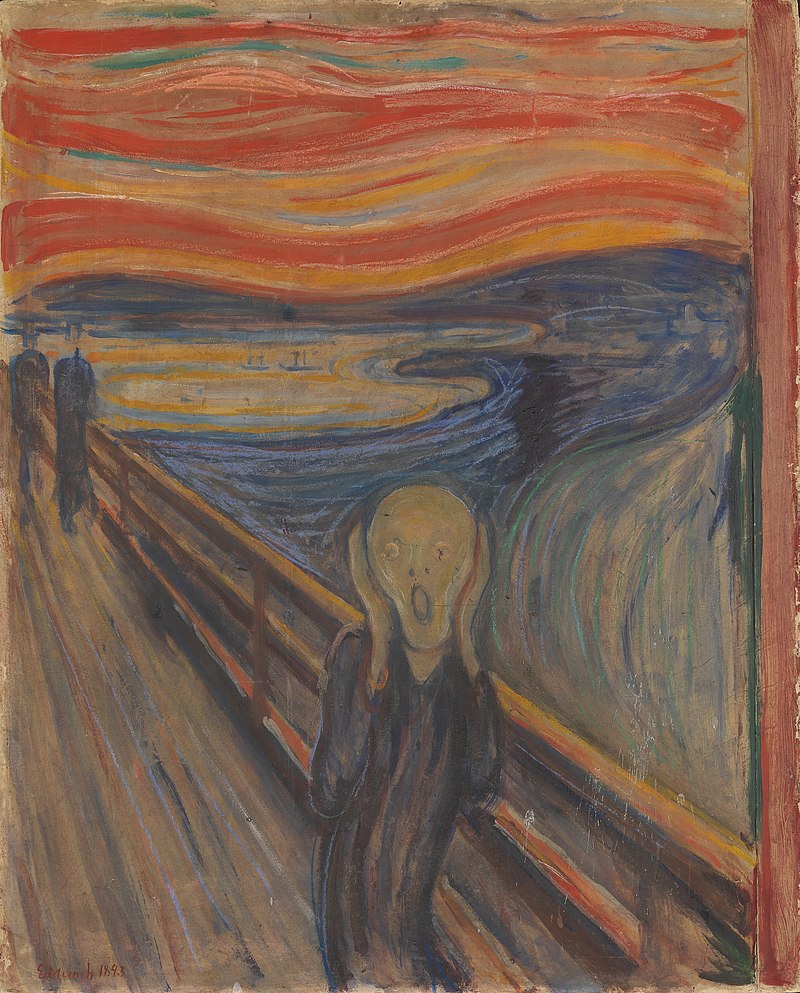

Expressionism (1900-1930s)

Edvard Munch was a precursor in the late 19th century with his famous Scream.

Expressionism was the art of emotion: unnatural and vivid colours, distorted forms and faces, and an almost nightmarish intensity.

Edvard Munch was a precursor in the late 19th century with his famous Scream.

Expressionism was the art of emotion: unnatural and vivid colours, distorted forms and faces, and an almost nightmarish intensity.

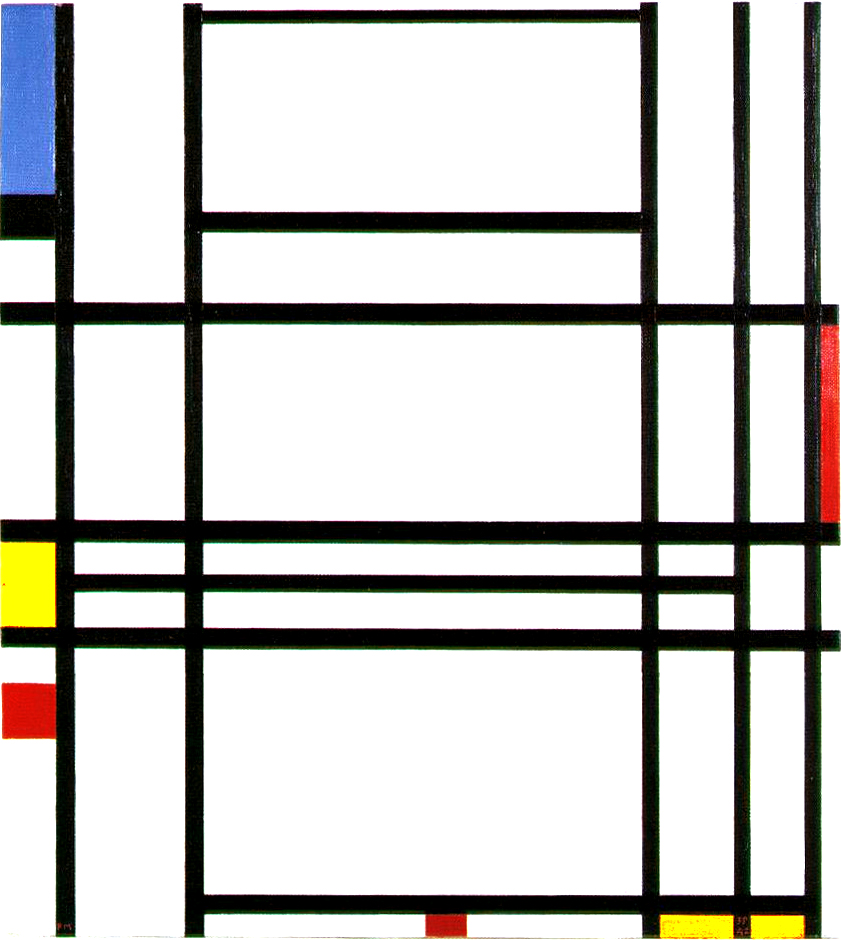

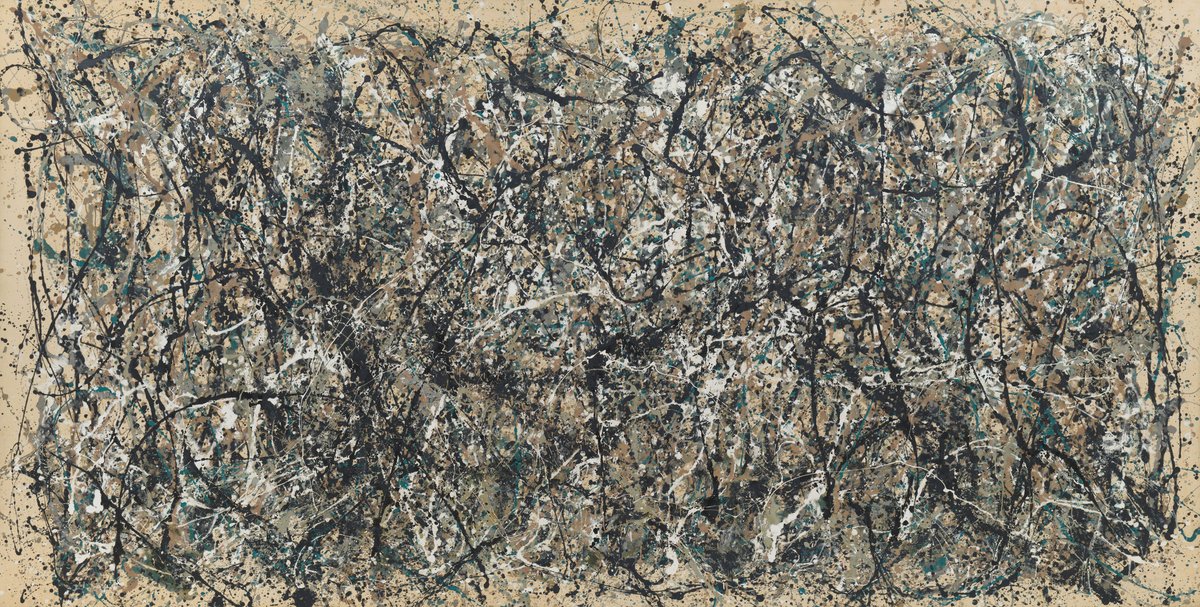

Abstract (1900-1960s)

Within the broad school of Abstract Art there is everything from the sharp geometry of Kasimir Malevich's Suprematism to the abstract shapes of Piet Mondrian or Hilma af Klint and the wilderness of Jackson Pollock.

Art had changed decisively.

Within the broad school of Abstract Art there is everything from the sharp geometry of Kasimir Malevich's Suprematism to the abstract shapes of Piet Mondrian or Hilma af Klint and the wilderness of Jackson Pollock.

Art had changed decisively.

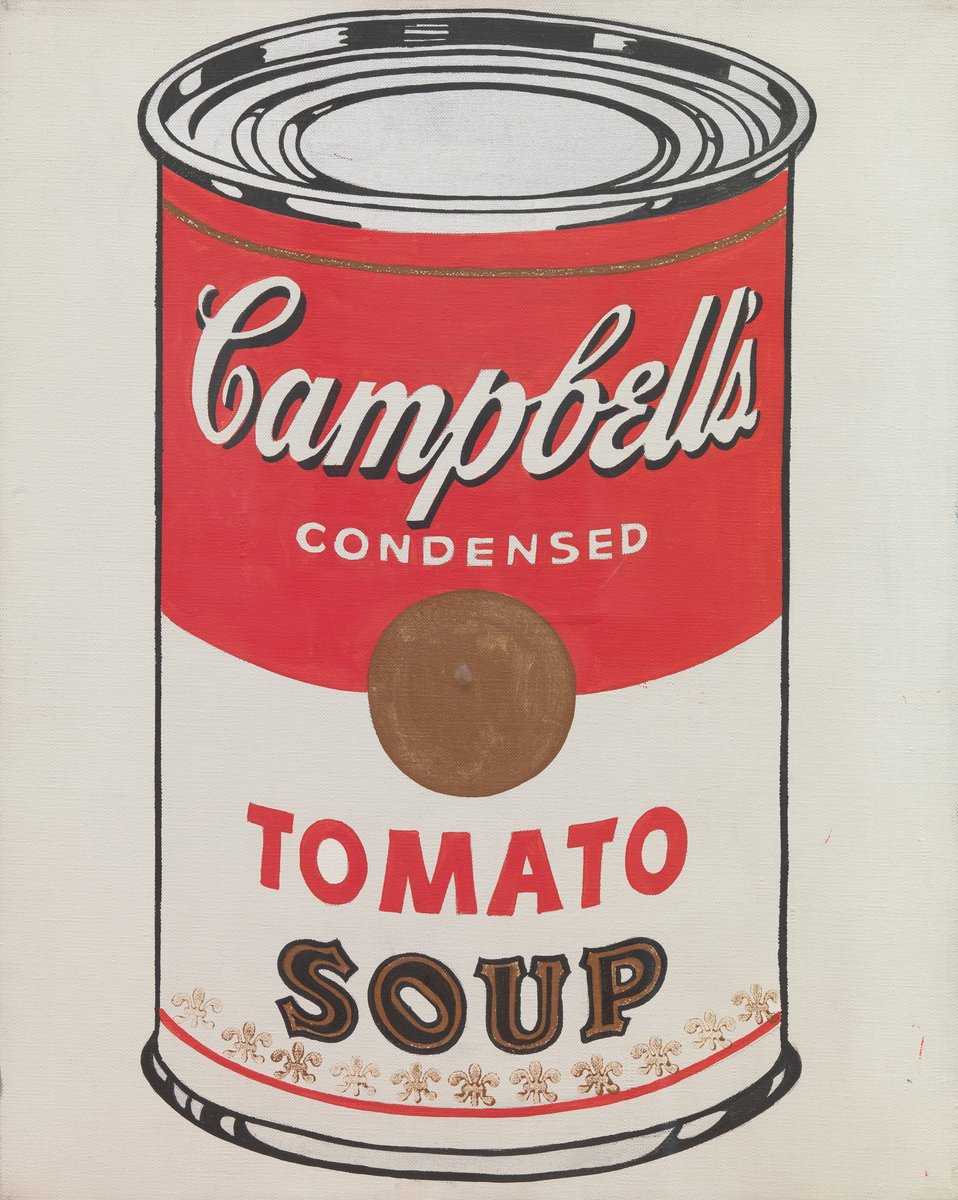

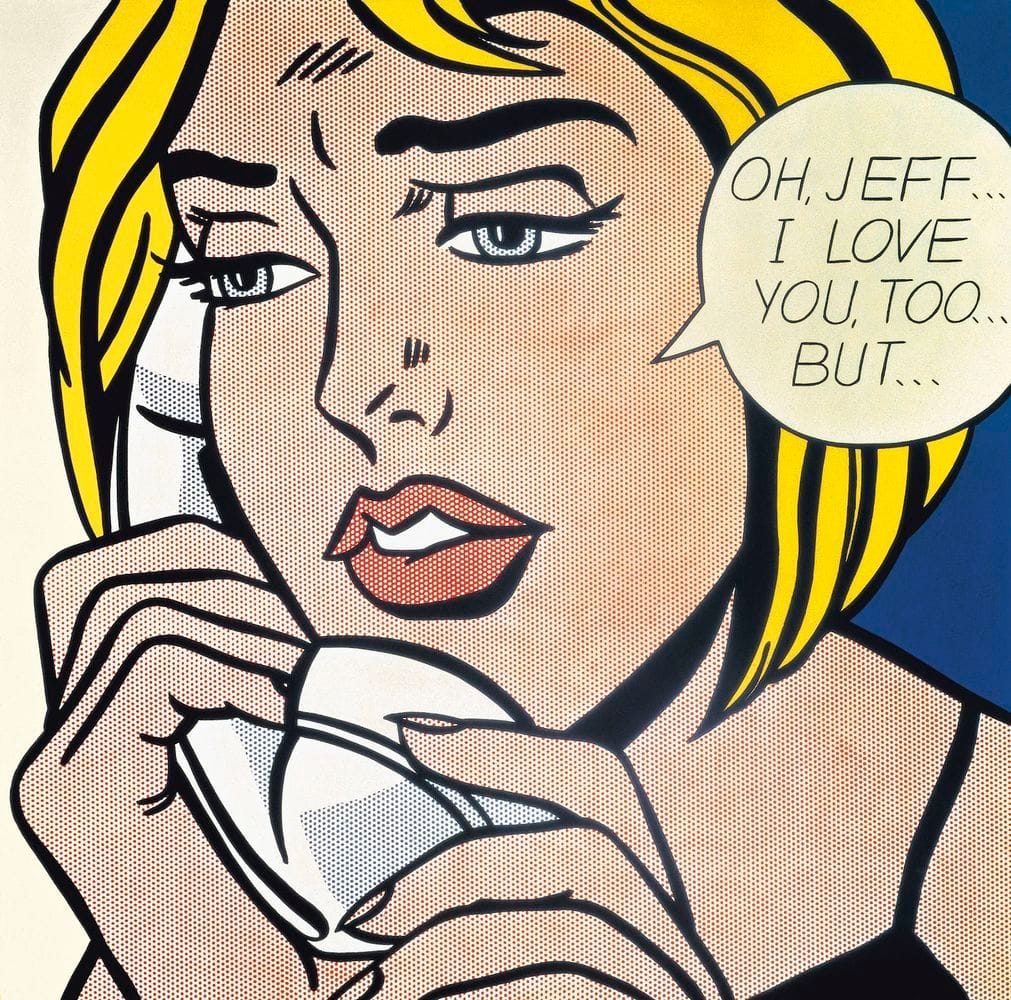

Pop Art (1950s-1970s)

Roy Lichtenstein, who alongside Andy Warhol was the definitive Pop Art artist, said that he realised galleries would accept anything as art — even urinals — apart from advertisements and the popular art of, say, comic books.

Thus Pop Art was born.

Roy Lichtenstein, who alongside Andy Warhol was the definitive Pop Art artist, said that he realised galleries would accept anything as art — even urinals — apart from advertisements and the popular art of, say, comic books.

Thus Pop Art was born.

This is an oversimplified and non-comprehensive list.

Each of these movements have many subdivisions of their own, and most of them are only from western art anyway.

There is a world of art out there, almost too voluminous and varied to be quantified.

Each of these movements have many subdivisions of their own, and most of them are only from western art anyway.

There is a world of art out there, almost too voluminous and varied to be quantified.

But, then again, all these "isms" aren't even that important. No movement ever painted a picture — only a person can do that.

Understanding art — if that's even possible! — isn't about being able to tell the difference between Mannerism and Baroque.

Understanding art — if that's even possible! — isn't about being able to tell the difference between Mannerism and Baroque.

And so, even if thinking about movements can be helpful, it can also be distracting.

We mustn't confuse recognising when and who painted something for understanding it or appreciating it fully.

In fact, you're probably best off knowing nothing about "movements" at all...

We mustn't confuse recognising when and who painted something for understanding it or appreciating it fully.

In fact, you're probably best off knowing nothing about "movements" at all...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter