Can the oil and gas industry play a constructive role in transitions? This is one of the burning questions for the climate. Today, the @IEA released a massive new report on the subject. Let’s dive in for a quick one, shall we?

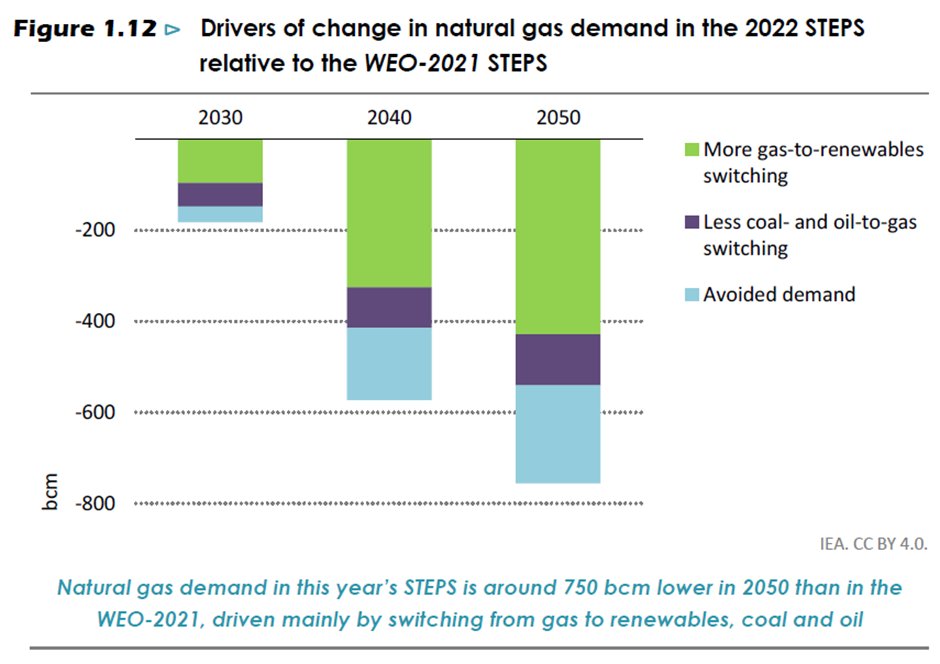

If you’re an oil and gas company, how do you play a part in transitions, especially now that a peak in fossil fuels is visible before 2030? How do you plan for a scenario reaching net zero where, for every dollar invested in fossil fuels, 10 dollars gets invested in clean energy?

Essentially, you have 2 choices: the first is to disappear. This means winding down operations, not investing in new fields, returning cash to shareholders, and cutting scope 1+2 emissions on your way out. Not selling your assets to a company with low ESG standards would be ideal

The second option is to invest in clean energy to future-proof your business. There are many different routes: create a subsidiary, go into the innovation ecosystem with VC, go the M&A route, set up your own shop, or partner up with clean energy firms. The list is endless.

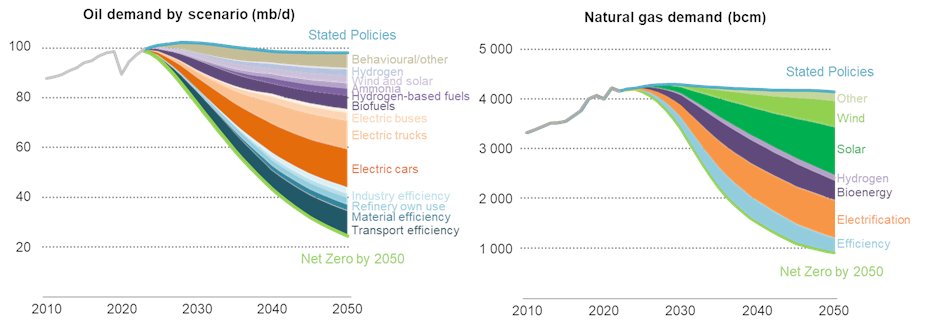

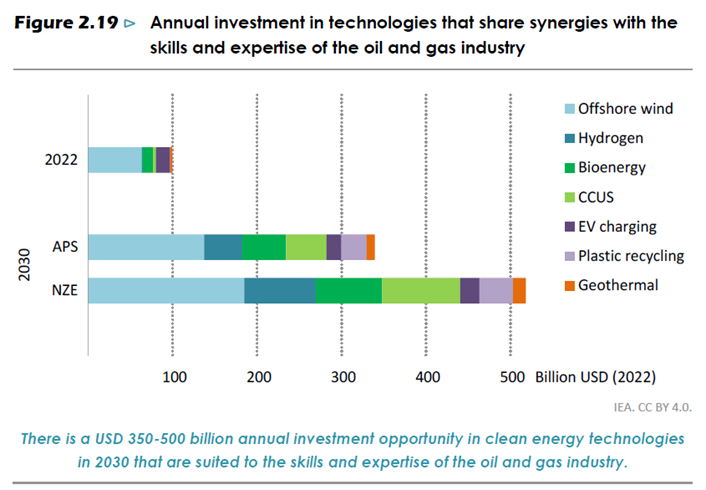

As for technologies – take your pick: solar, wind, biofuels, biogas, synthetic fuels, electrolysers, grids, geothermal, … this is all the stuff that will replace oil and gas, so why not invest in them instead?

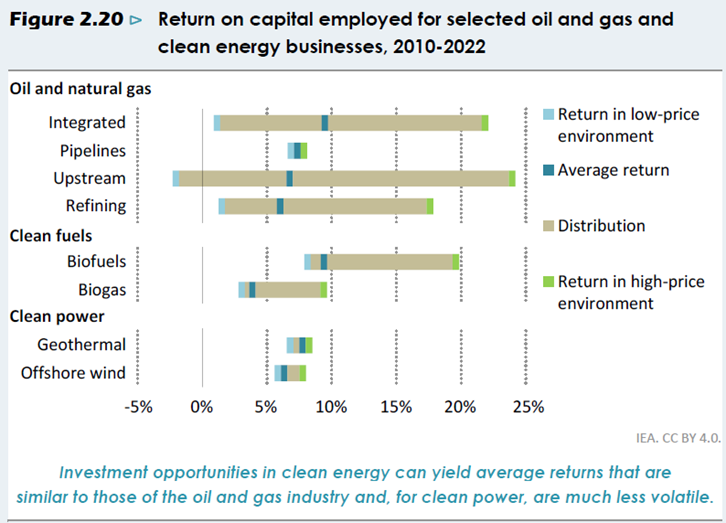

“Because returns are low/there are no bankable projects.” This is a common refrain. But looking back, clean energy yields a 6% return. Not as good as the 6-9% average return on capital invested in oil and gas, but decent… and generally more reliable!

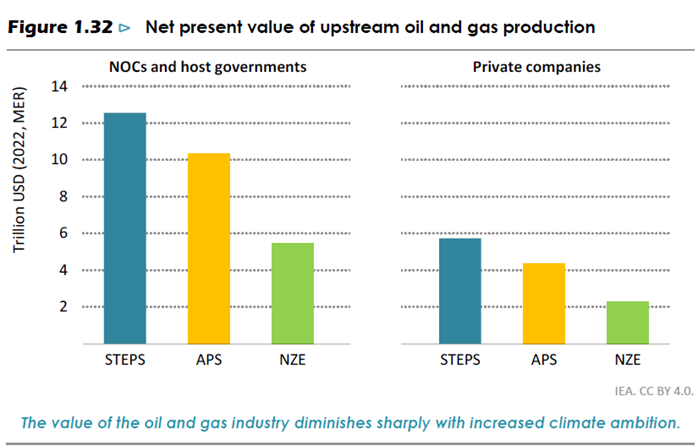

And anyway, who says selling oil and gas will remain profitable in the years ahead? If governments meet their climate ambitions, the value of today’s private oil and gas companies will drop by 25%. If the world reaches 1.5°C, it will be cut in half.

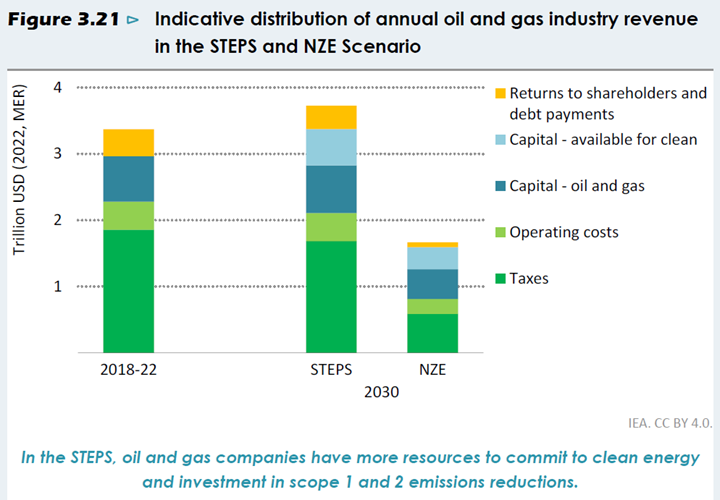

If you think the NZE is unlikely, then know that the capital available to spend on clean energy is even higher in STEPS, because oil and gas demand and prices are higher, leaving more money to throw around. So diversification is sensible risk management, whatever the scenario.

There’s no one solution that makes sense for all, but the oil and gas industry generally has some unique strengths – they are good at drilling holes in the ground, carrying gases and liquids around the world, financing and executing big, capital-intensive projects, etc.

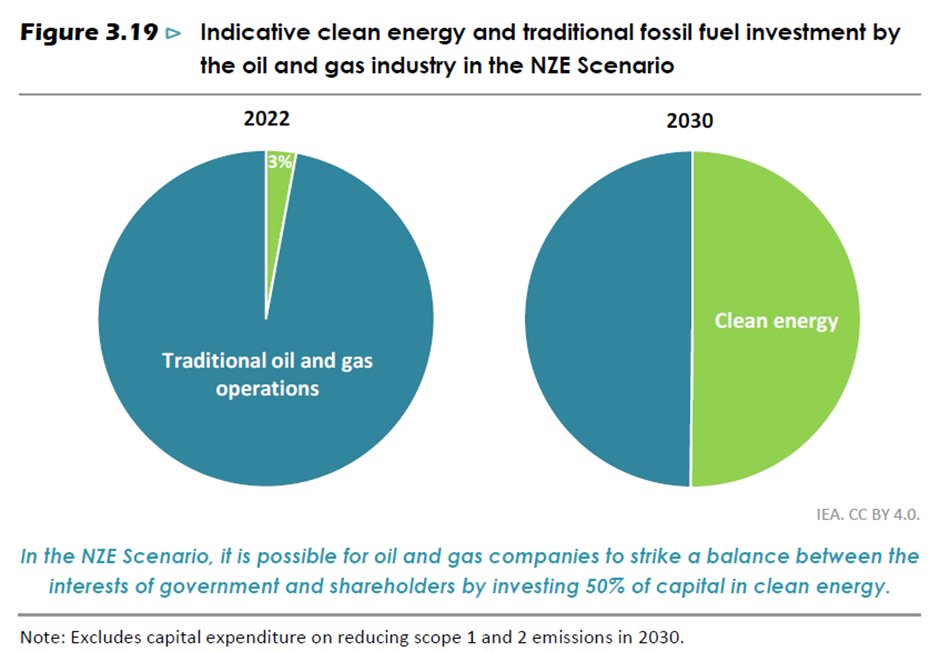

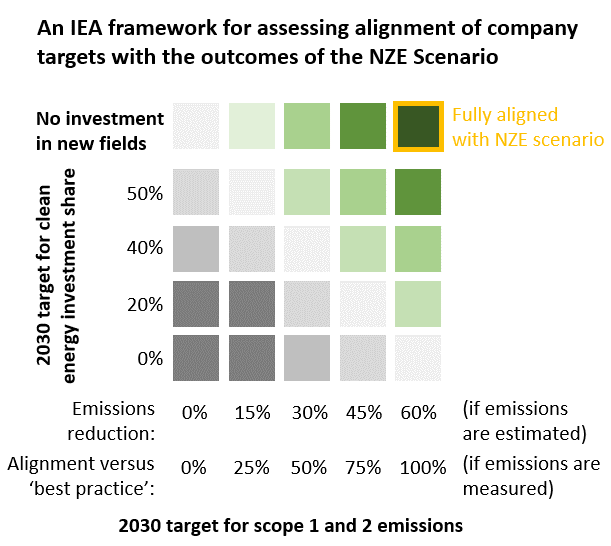

Today, the oil and gas industry invests 2.5% of its capital on clean energy. By 2030, based on our bottom-up assessment of oil and gas demand, supply, prices, and revenue, it could be possible to spend 50% of total CAPEX on clean energy to align with net zero by 2050.

This is a key part of our framework to assess oil and gas industry alignment with net zero transitions. It gives more nuance to companies and financial actors, allowing them some bandwidth to choose the most appropriate pathway based on their skills, resources and strategy.

Follow the launch live with here, with starts in 2 minutes:

And the report itself: iea.org/events/the-oil…

iea.li/3R79gDf

And the report itself: iea.org/events/the-oil…

iea.li/3R79gDf

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh