Gianlorenzo Bernini was born in Naples in 1598. His father Pietro was a successful sculptor and he taught his son everything he knew.

They moved to Rome in 1606 when Pietro was commissioned to decorate a church there, and Gianlorenzo's education continued...

They moved to Rome in 1606 when Pietro was commissioned to decorate a church there, and Gianlorenzo's education continued...

In Rome, under the careful tutelage of his father and later working alongside him, Bernini blossomed into a prodigiously talented artist.

He made this statue when he was only 17; no wonder Pope Paul V said "this child will be the Michelangelo of his age."

He made this statue when he was only 17; no wonder Pope Paul V said "this child will be the Michelangelo of his age."

Thus started Bernini's long career in Rome — he received patronage from a succession of Popes and Cardinals, most of all Maffeo Barberini (later Pope Urban VIII) and Scipione Borghese.

Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius was one of the statues Bernini made for Borghese... he was 22.

Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius was one of the statues Bernini made for Borghese... he was 22.

Bernini worked almost relentlessly for six decades, producing an immense volume of work and slowly reshaping the city of Rome itself.

Borghese gave Bernini the chance to prove himself and soon enough everybody wanted Bernini to make them one of his famously lifelike busts.

Borghese gave Bernini the chance to prove himself and soon enough everybody wanted Bernini to make them one of his famously lifelike busts.

Bernini was praised for his technical ability; his skill in carving marble was literally unmatched. This young sculptor could make stone look like anything.

Consider the sling from his statue of David. This is marble, but it looks as taught as real rope:

Consider the sling from his statue of David. This is marble, but it looks as taught as real rope:

Or consider Daphne's hands from Daphne and Apollo, or the hand of Pluto on Proserpina's thigh, or Proserpina's tears.

There was seemingly nothing Bernini couldn't do with marble.

Both of these were made in Bernini's early career when he was working for Scipione Borghese.

There was seemingly nothing Bernini couldn't do with marble.

Both of these were made in Bernini's early career when he was working for Scipione Borghese.

Bernini didn't make all his sculptures alone.

As the years went by he increasingly relied on a small group of trusted assistants. Bernini designed statues for his commissions; they executed his designs.

Thus Noli Me Tangere was designed by Bernini but carved by Antonio Raggi.

As the years went by he increasingly relied on a small group of trusted assistants. Bernini designed statues for his commissions; they executed his designs.

Thus Noli Me Tangere was designed by Bernini but carved by Antonio Raggi.

Bernini was an artistic force of nature who did things that literally nobody else could; thus he inspired a generation of imitators.

And his style — all full of life and detail and drama and dynamism — almost singlehandely defined a new art movement: the Baroque.

And his style — all full of life and detail and drama and dynamism — almost singlehandely defined a new art movement: the Baroque.

Baroque Art, in both painting and sculpture, was defined by high drama, intense emotion, exuberant decoration, manifold details, and movement.

Just compare Bernini's David with Michelangelo's David, from 1504, to get a sense of the difference between Renaissance and Baroque Art.

Just compare Bernini's David with Michelangelo's David, from 1504, to get a sense of the difference between Renaissance and Baroque Art.

The commissions came thick and fast from all across Europe, but it was the interior of St Peter's Basilica to which Bernini dedicated most of his time and work.

He made the Baldachin, the Chair of St Peter, and countless more tombs, sculptures, and decorations throughout.

He made the Baldachin, the Chair of St Peter, and countless more tombs, sculptures, and decorations throughout.

And he was not only a sculptor — Bernini was also a painter, a set designer, an urban planner, and an architect.

He created a number fountains that still grace the streets of Rome, perhaps most eye-catchingly of all the elaborate Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi.

He created a number fountains that still grace the streets of Rome, perhaps most eye-catchingly of all the elaborate Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi.

His architectural masterpiece was the colonnade outside St Peter's Basilica.

Nothing like this had been built before. All the rules of Classical and Renaissance architecture were reinvented by Bernini.

Little wonder he was the Vatican's favourite artist.

Nothing like this had been built before. All the rules of Classical and Renaissance architecture were reinvented by Bernini.

Little wonder he was the Vatican's favourite artist.

Rarely has an artist dominated their age like Bernini. The city of Rome was shaped, its atmosphere created, its culture guided, by Bernini's sculptures and architecture.

Kings, Queens, Popes, and Cardinals chased him; he was *the* artistic superstar of 17th century Europe.

Kings, Queens, Popes, and Cardinals chased him; he was *the* artistic superstar of 17th century Europe.

It's not hard to see why Bernini was so highly praised.

What the Renaissance had started, with its dreams of matching the sculptors of Ancient Greece and Rome, Bernini had taken to its technical zenith.

He could make marble look as light as air — literally.

What the Renaissance had started, with its dreams of matching the sculptors of Ancient Greece and Rome, Bernini had taken to its technical zenith.

He could make marble look as light as air — literally.

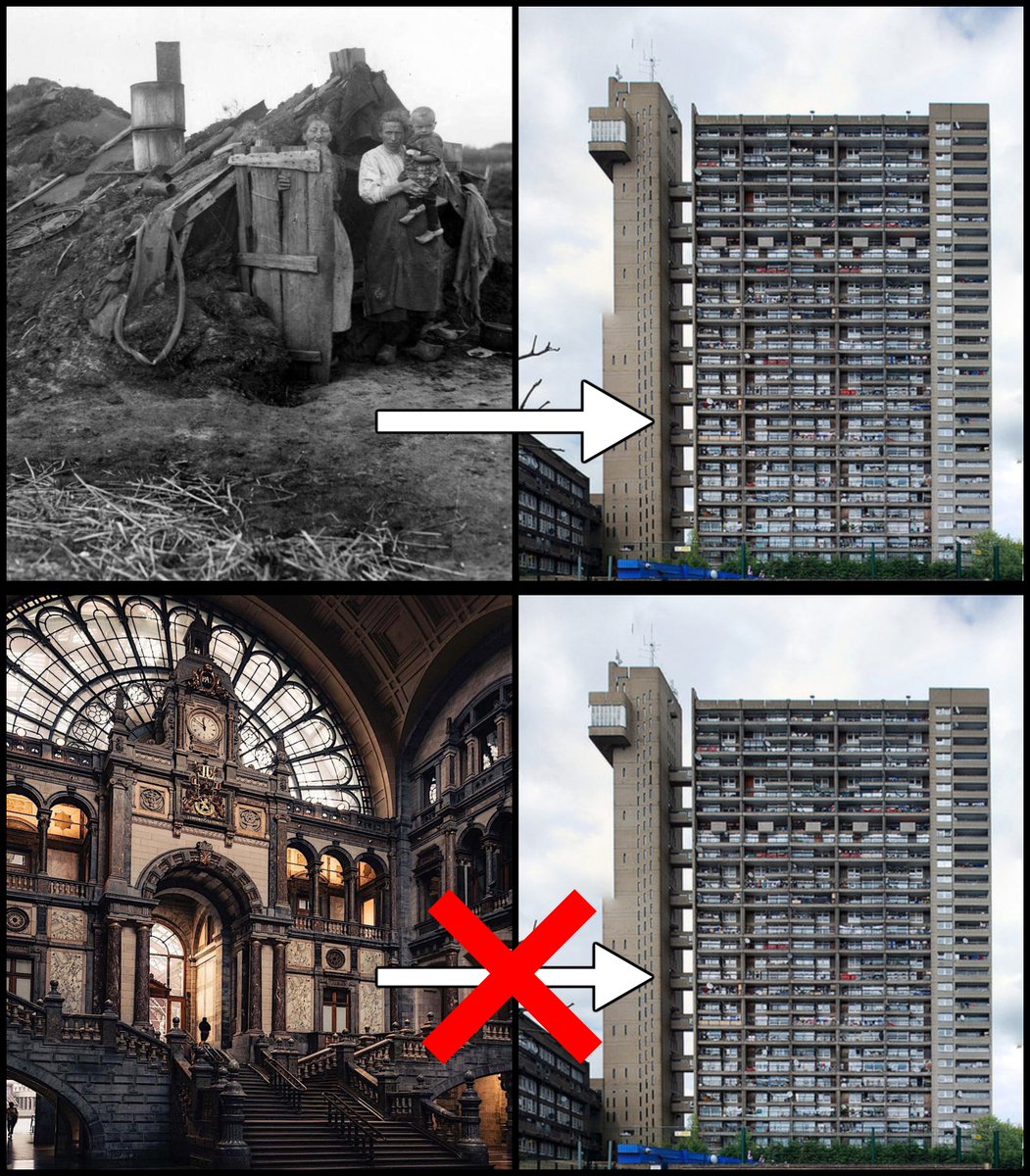

But this is exactly why Bernini has been criticised.

In the 18th century, with Neoclassicism on the rise, philosophers like Joachim Winckelman argued Bernini's art was too dynamic and emotional.

It lacked the intellectual might and solemn grandeur of Ancient Greek sculpture:

In the 18th century, with Neoclassicism on the rise, philosophers like Joachim Winckelman argued Bernini's art was too dynamic and emotional.

It lacked the intellectual might and solemn grandeur of Ancient Greek sculpture:

Others have argued that Bernini's use of marble was ridiculous.

As in the Ecstacy of Saint Teresa, Bernini delighted in elaborate designs of almost incomprehensible intricacy.

Some have called this idolatry; people venerated the art and artist rather than the saint it depicts.

As in the Ecstacy of Saint Teresa, Bernini delighted in elaborate designs of almost incomprehensible intricacy.

Some have called this idolatry; people venerated the art and artist rather than the saint it depicts.

These critics said that Bernini prized technical mastery over real meaning or depth; we admire his ability, but do we actually admire the art itself?

Is it genuinely moving? Or are we merely impressed in a superficial way by something that we could not have done ourselves?

Is it genuinely moving? Or are we merely impressed in a superficial way by something that we could not have done ourselves?

What is the point of making marble flutter like cloth, after all?

Is art improved by a perfect imitation of reality, or is there something more than mere technical perfection to beauty and meaning?

Is art improved by a perfect imitation of reality, or is there something more than mere technical perfection to beauty and meaning?

When making a bust of King Louis XIV of France somebody said that whereas a painter could drape a lock of hair across the forehead of a portrait, marble made this impossible for sculptors.

Bernini proved him wrong — but only by cutting back Louis' forehead and ruining the bust.

Bernini proved him wrong — but only by cutting back Louis' forehead and ruining the bust.

He has also been criticised for the luxury and extravagance of his art.

A Scottish architect called Colen Campbell said his statues were "capricious ornaments... affected and licentious", and that he had "endeavoured to debauch Mankind with his odd and chimerical Beauties."

A Scottish architect called Colen Campbell said his statues were "capricious ornaments... affected and licentious", and that he had "endeavoured to debauch Mankind with his odd and chimerical Beauties."

Such criticisms have been made against Baroque Art more generally, including Bernini's contemporaries Pietro da Cortona and Borromini.

They say Baroque Art is decadent, that it lacks seriousness, piety, or deeper beauty; that it is all show and no meaning, all hand and no heart.

They say Baroque Art is decadent, that it lacks seriousness, piety, or deeper beauty; that it is all show and no meaning, all hand and no heart.

Love him or hate him, the influence of Bernini cannot be denied — he dominated 17th century Rome and almost singlehandedly created Baroque Art.

Whether or not that influence was good depends on your tastes and beliefs.

So... what do you think of Bernini?

Whether or not that influence was good depends on your tastes and beliefs.

So... what do you think of Bernini?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter