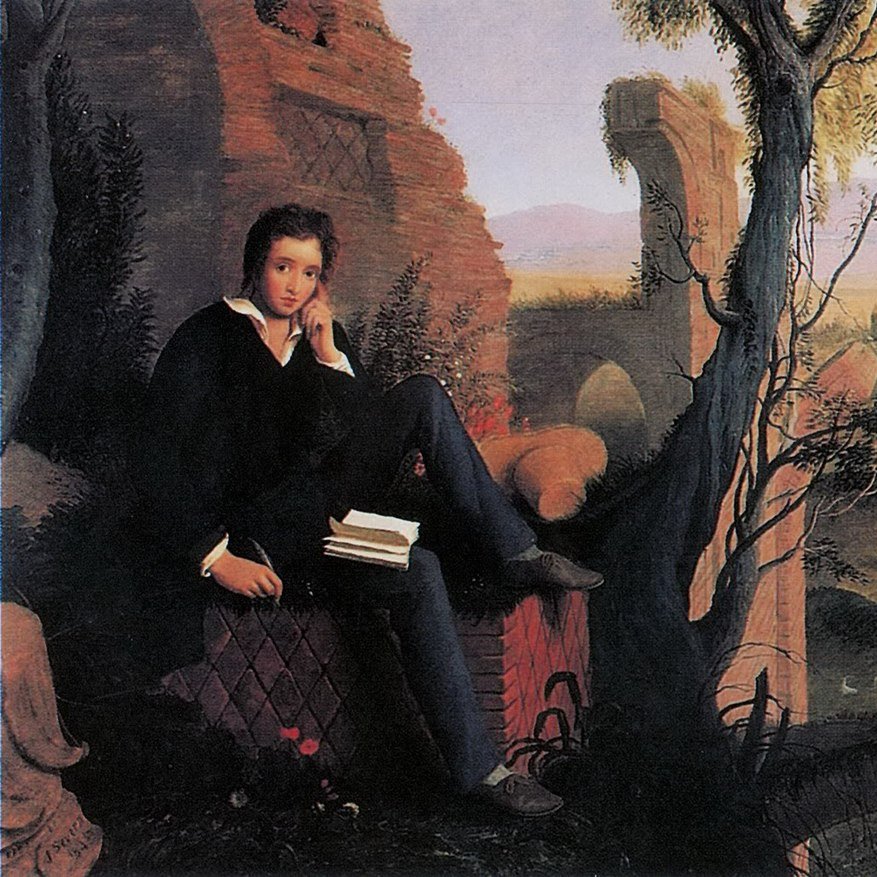

You probably haven't seen the statue that inspired Ozymandias, the famous poem by Percy Shelley.

But Shelley never saw the statue either — and that's exactly why it is such a good poem.

So here's the story of Ozymandias, and why "realism" isn't always good for art...

But Shelley never saw the statue either — and that's exactly why it is such a good poem.

So here's the story of Ozymandias, and why "realism" isn't always good for art...

When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 he took with him scholars and archaeologists, who sent their research, drawings, and findings back to Europe.

The continent was gripped by "Egyptomania."

Books, architecture, art, furniture, interior design — it was all about Ancient Egypt.

The continent was gripped by "Egyptomania."

Books, architecture, art, furniture, interior design — it was all about Ancient Egypt.

Scholars continued to work in Egypt for decades, sending a steady stream of the artefacts they had taken back to Europe.

And everybody, including Napoleon, had been after one thing: a colossal, collapsed statue of Ramesses II, created in 1,200 BC and once over 60 feet tall.

And everybody, including Napoleon, had been after one thing: a colossal, collapsed statue of Ramesses II, created in 1,200 BC and once over 60 feet tall.

In 1815 the British Consul hired an Italian explorer called Giovanni Belzoni to get the statue. It was in the "Ramesseum", a temple built to the glory of Ramesses in Luxor — in the far south of Egypt.

News spread in Europe that this legendary statue was finally on its way.

News spread in Europe that this legendary statue was finally on its way.

The statue became known as the "Younger Memnon" because the Ramesseum had been referred to in classical times as the Memnonium, from a mythical Greek king.

Ramesses, meanwhile, was known as Ozymandias; that was the Greek transliteration of his royal name, Usermaatre.

Confusing.

Ramesses, meanwhile, was known as Ozymandias; that was the Greek transliteration of his royal name, Usermaatre.

Confusing.

Excitement spread in England.

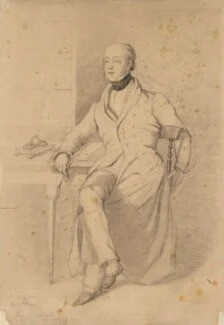

And, inspired by the idea of this broken statue of a once-mighty ruler surrounded by empty sands, Percy Shelley and his friend and fellow poet Horace Smith decided to have a private competition.

Who could write the best poem about it?

And, inspired by the idea of this broken statue of a once-mighty ruler surrounded by empty sands, Percy Shelley and his friend and fellow poet Horace Smith decided to have a private competition.

Who could write the best poem about it?

It was the age of Romanticism, after all.

Poets, painters, and composers were gripped by emotional grandeur, by tragedy, by the beauty of nature.

Consider the paintings of Friedrich, Turner, or Martin — human glory overcome by nature and the ravages of time.

Poets, painters, and composers were gripped by emotional grandeur, by tragedy, by the beauty of nature.

Consider the paintings of Friedrich, Turner, or Martin — human glory overcome by nature and the ravages of time.

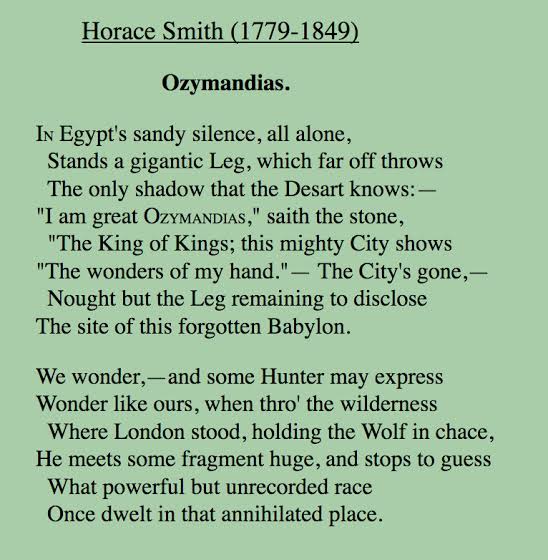

This was Horace Smith's poem, also titled Ozymandias, published in 1818.

Similar to Shelley's version, but lacking his lyrical dignity — "a gigantic Leg" sounds odd.

Although his inclusion of the image of a future generation finding the ruins of London is powerful.

Similar to Shelley's version, but lacking his lyrical dignity — "a gigantic Leg" sounds odd.

Although his inclusion of the image of a future generation finding the ruins of London is powerful.

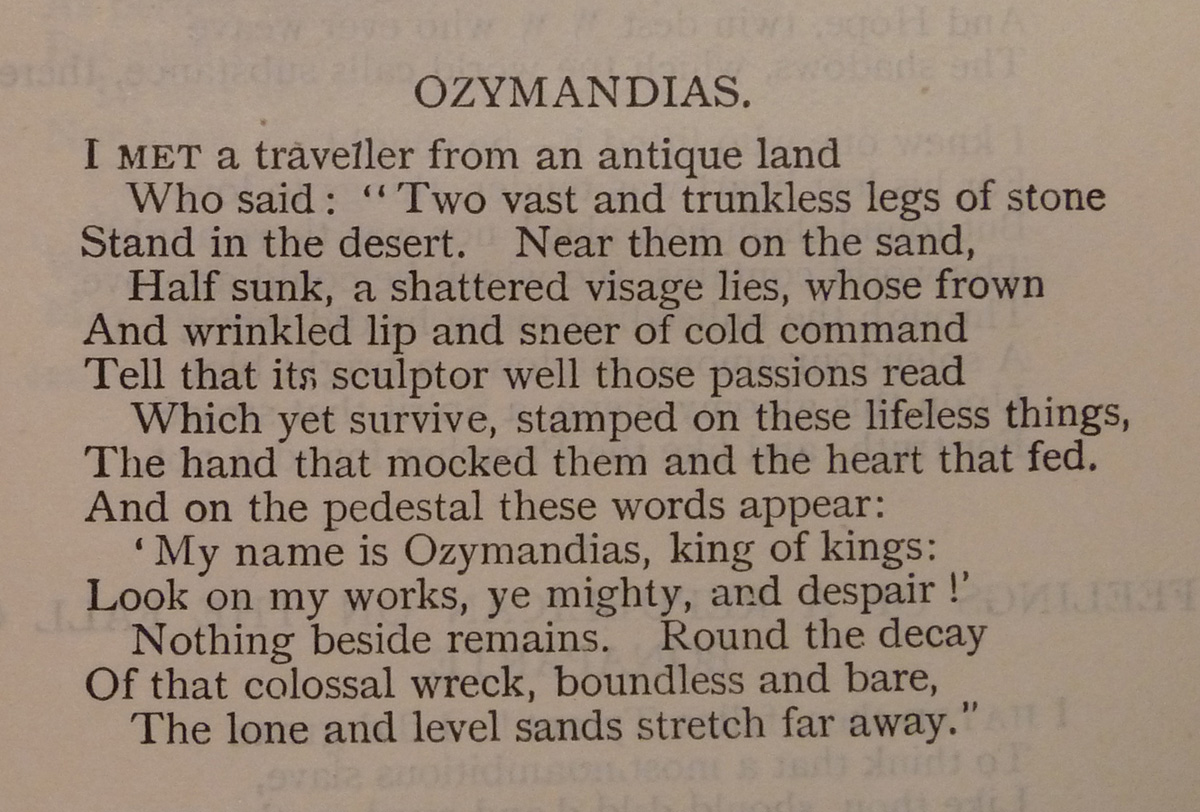

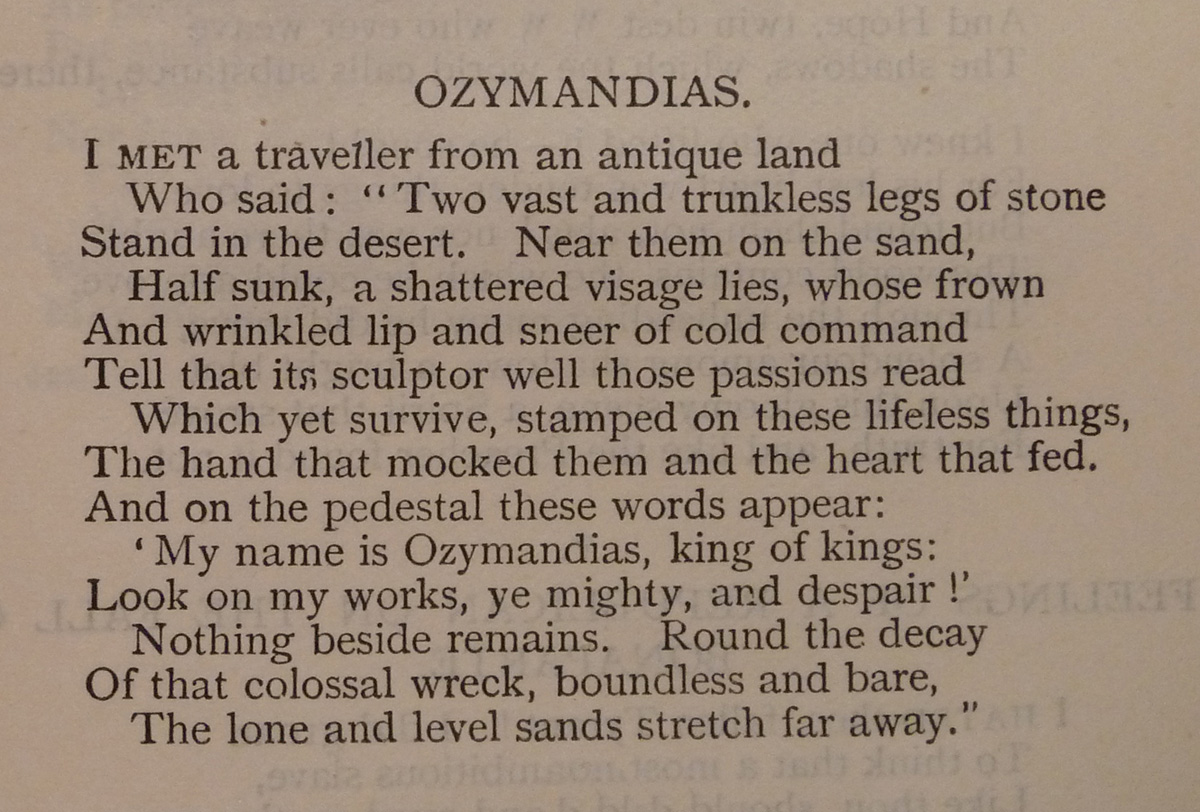

And here is Shelley's legendary Ozymandias. He wrote in December 1817, and it was published the following year.

"Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!" / Nothing beside remains.

Two haunting, ironic, unforgettable lines to capture the heart of Romanticism.

"Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!" / Nothing beside remains.

Two haunting, ironic, unforgettable lines to capture the heart of Romanticism.

And here is the statue, the famous Younger Memnon itself.

But where are the "sneer", "wrinkled lip", and "frown" Shelley wrote of? Ramesses' expression is inscrutable, and at most might be described as... friendly?

Shelley never saw the statue of Ozymandias.

But where are the "sneer", "wrinkled lip", and "frown" Shelley wrote of? Ramesses' expression is inscrutable, and at most might be described as... friendly?

Shelley never saw the statue of Ozymandias.

The Younger Memnon arrived in 1818 but did not arrive at the British Museum until 1821.

And, anyway, in March of 1818 Shelley had left England with his wife, Mary (whose Frankenstein had recently been published), and gone into self-imposed exile in Italy, never to return.

And, anyway, in March of 1818 Shelley had left England with his wife, Mary (whose Frankenstein had recently been published), and gone into self-imposed exile in Italy, never to return.

Would Shelley's poem have been "better" if he had seen the statue? No.

All Shelley needed was the *thought* of that statue of once-glorious Ramesses, ruined and unobserved in the desert, and Ozymandias simply came to him.

Seeing the statue would have impeded his imagination.

All Shelley needed was the *thought* of that statue of once-glorious Ramesses, ruined and unobserved in the desert, and Ozymandias simply came to him.

Seeing the statue would have impeded his imagination.

There is a broader point here about realism in art.

Not capital R "Realism", which was a specific 19th century movement, but the general demand that art should be as "realistic" as possible.

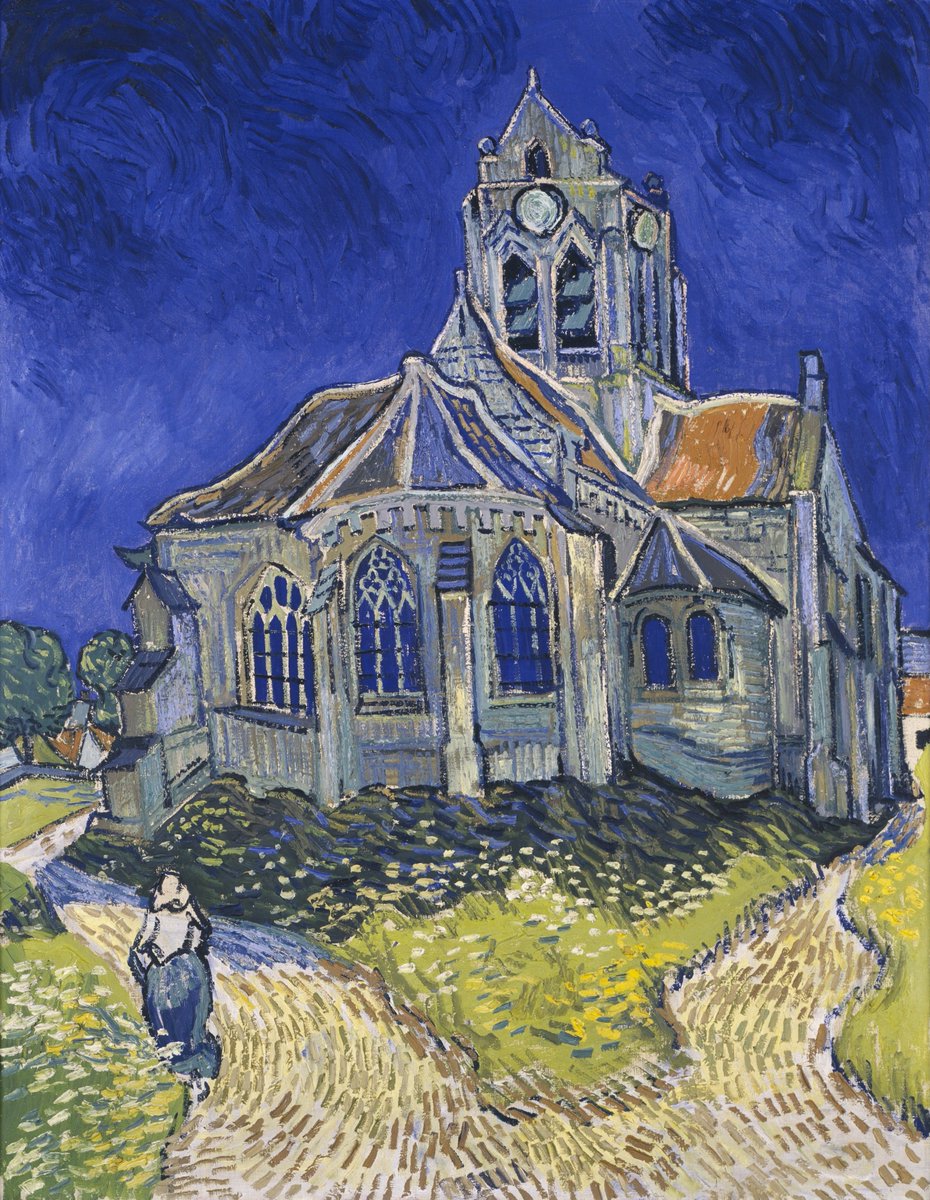

This is untrue; cold realism shackles art and always has. Was van Gogh "realistic?"

Not capital R "Realism", which was a specific 19th century movement, but the general demand that art should be as "realistic" as possible.

This is untrue; cold realism shackles art and always has. Was van Gogh "realistic?"

Even for an artist like Frederic Edwin Church, famous for his vast, glittering, highly detailed, quasi-photorealistic landscapes, the goal was never pure realism.

Take his painting of the Northern Lights — they don't actually look like that.

Does that make his painting "bad"?

Take his painting of the Northern Lights — they don't actually look like that.

Does that make his painting "bad"?

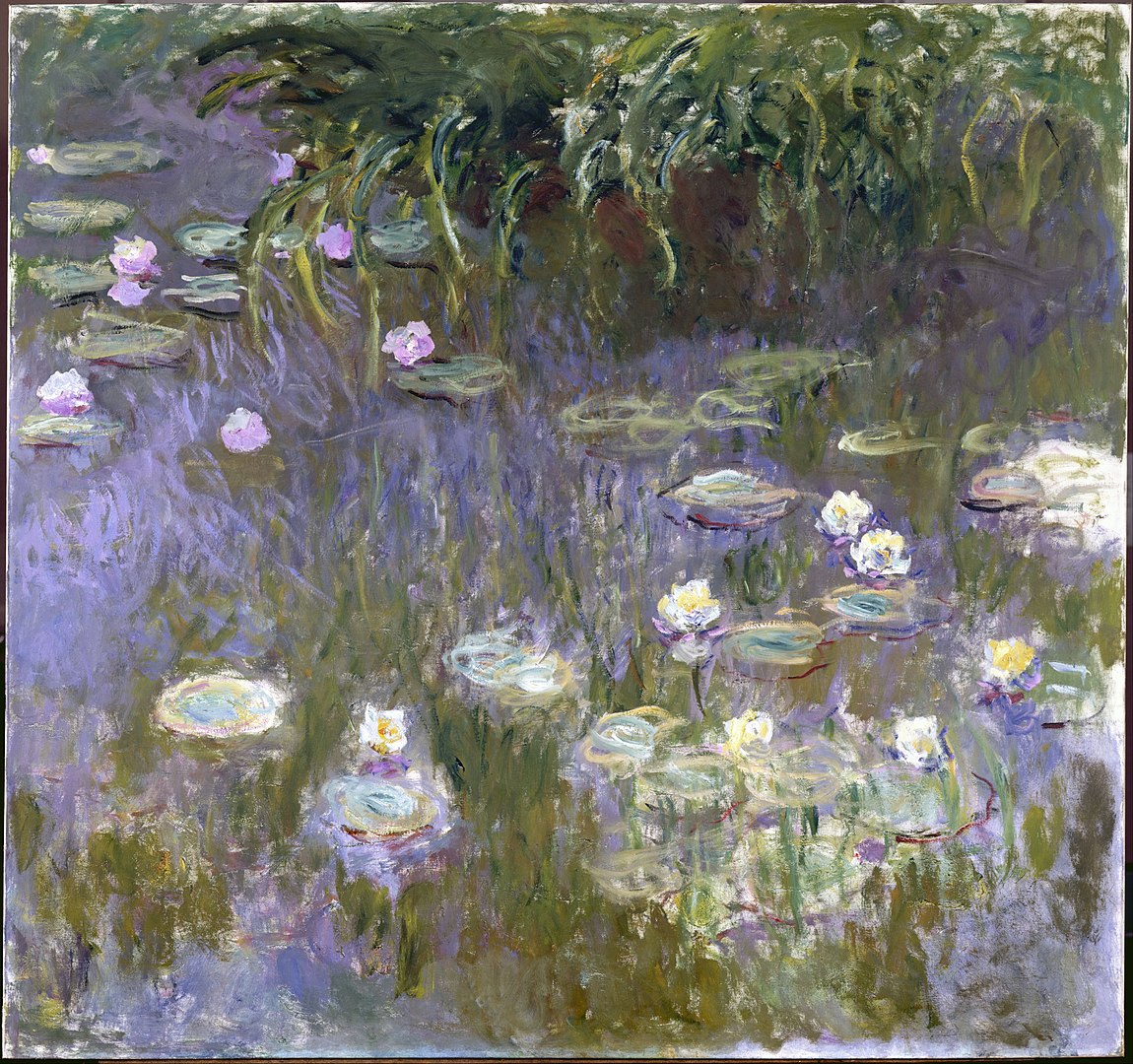

And what is Impressionism if not "unrealistic"?

Water lilies do not seem to look like this in the real world, and yet Claude Monet's paintings feel more realistic than any photograph or photorealistic painting ever could be.

Water lilies do not seem to look like this in the real world, and yet Claude Monet's paintings feel more realistic than any photograph or photorealistic painting ever could be.

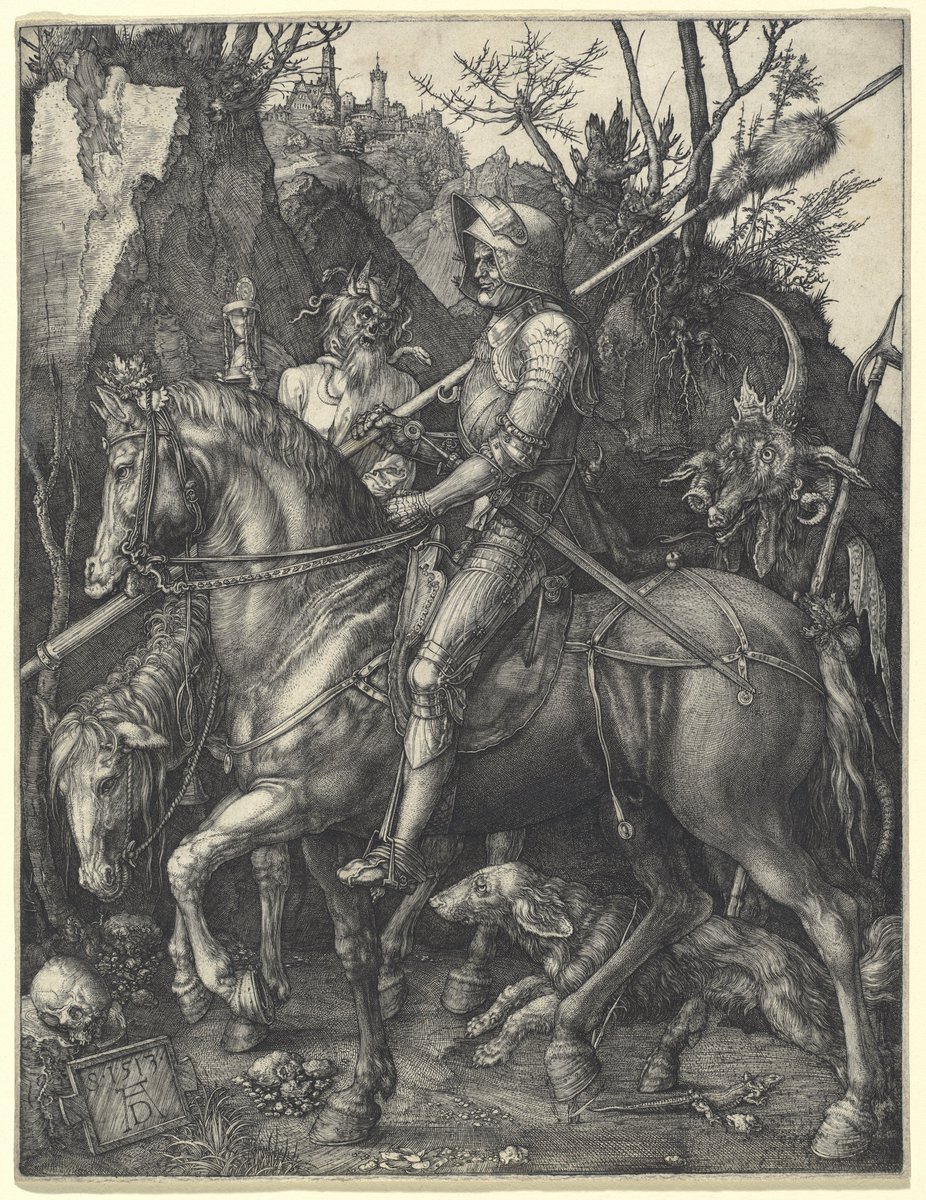

And what of the statues of Auguste Rodin? Or the prints of Utagawa Hiroshige? Or the engravings of Albrecht Dürer?

They are all clearly tied to reality in some sense, but they are not constrained by it. Realism would deaden whatever beauty, meaning, or power they have.

They are all clearly tied to reality in some sense, but they are not constrained by it. Realism would deaden whatever beauty, meaning, or power they have.

Cleaving to realism is peculiarly unartistic; it defeats the whole point of art.

Science is about things as they are in themselves; Art is about things as they relate to the human soul, heart, and imagination.

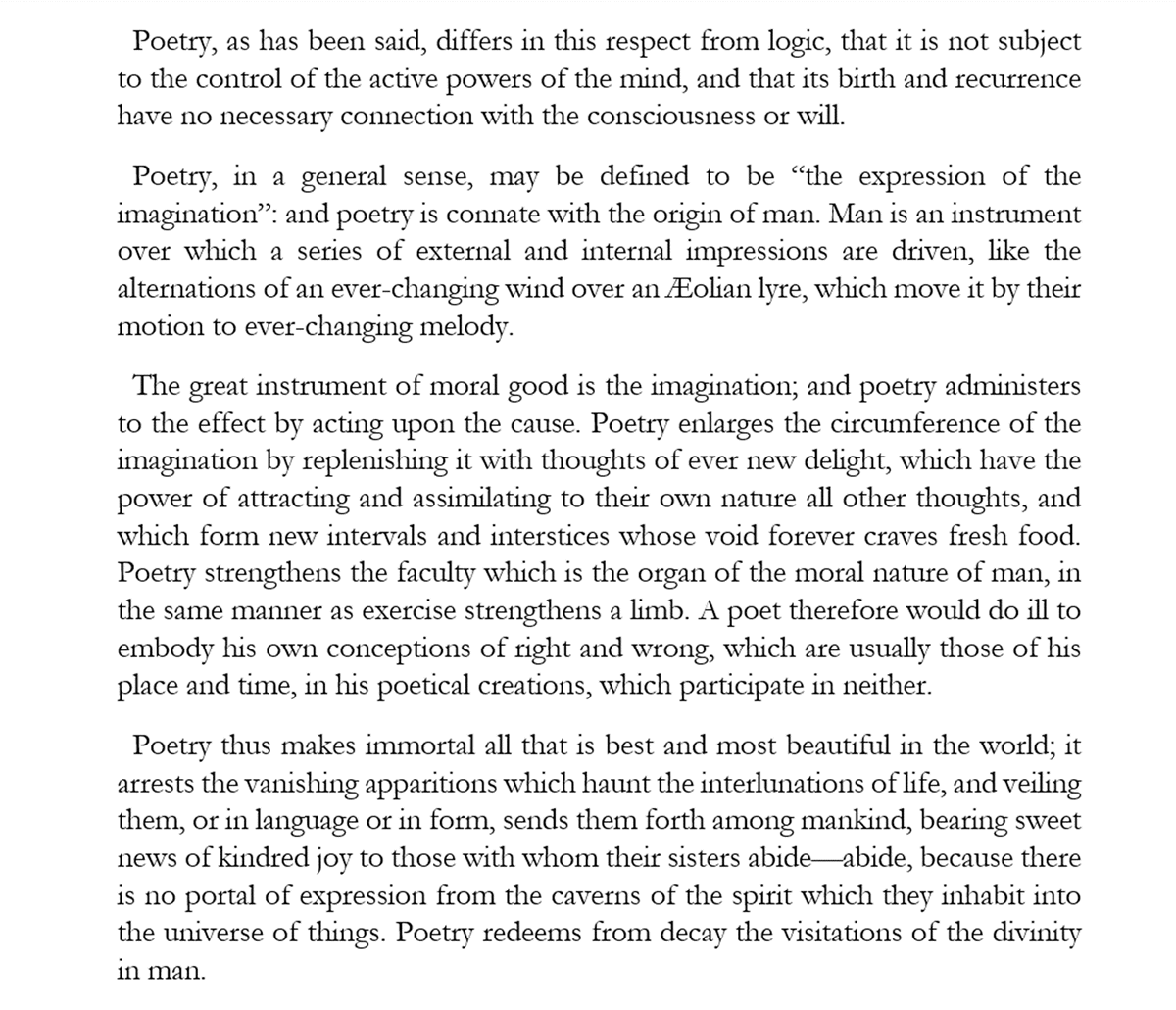

Thus said Shelley himself in his glorious "Defence of Poetry":

Science is about things as they are in themselves; Art is about things as they relate to the human soul, heart, and imagination.

Thus said Shelley himself in his glorious "Defence of Poetry":

Poetry's very "unrealism", focussing above all on the experience of a living human in this world rather than the cold facts of the universe, was what made it useful, beautiful, and worthwhile for humanity.

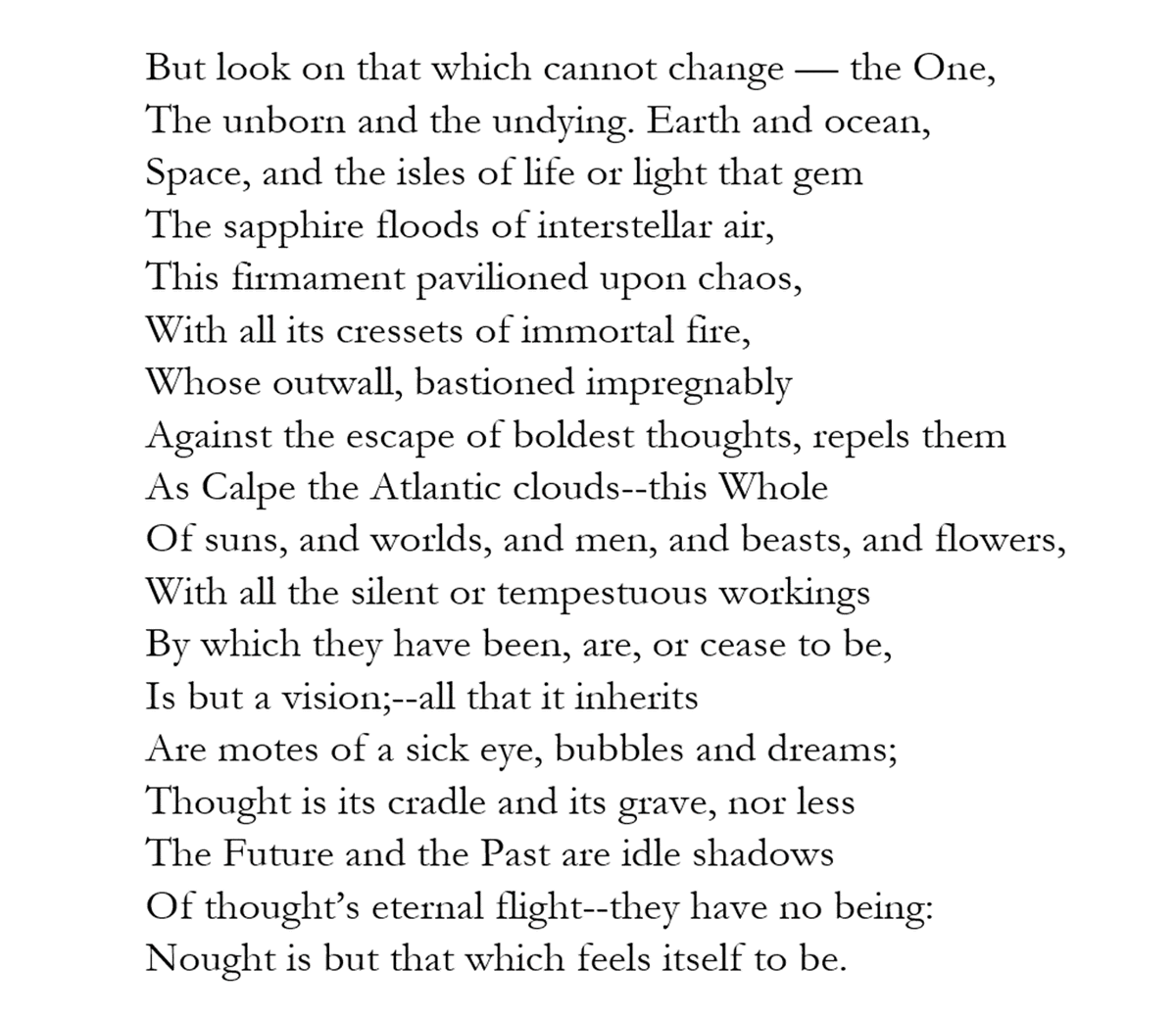

Best summarised by this excerpt from his dramtic poem Hellas:

Best summarised by this excerpt from his dramtic poem Hellas:

And so Ozymandias describes and imagines for us the feeling of fallen grandeur, of the passage of time and the transience of earthly power, better than any purely "realistic" or "factual" version ever could.

Shelley felt a deeper truth; we feel it with him.

Shelley felt a deeper truth; we feel it with him.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh