The Leaning Tower of Pisa might just be the most famous tower in the world.

But... what the hell is it? where is it? who built it? and why hasn't it fallen down yet?

All these questions (& more) answered here:

But... what the hell is it? where is it? who built it? and why hasn't it fallen down yet?

All these questions (& more) answered here:

The Leaning Tower of Pisa is known to all by a litany of witty tourist photographs. Little wonder, given its gravity-defying tilt!

But, as with anything so monstrously famous, the thing itself fades away and we know it merely as a silhouette devoid of context...

But, as with anything so monstrously famous, the thing itself fades away and we know it merely as a silhouette devoid of context...

So let us shine some light on this "Leaning Tower of Pisa."

First of all: where is it?

Pisa, of course. But where is Pisa? In Tuscany, Italy, about six miles from the sea and about fifty miles west of Florence.

First of all: where is it?

Pisa, of course. But where is Pisa? In Tuscany, Italy, about six miles from the sea and about fifty miles west of Florence.

And... what is it?

The Leaning Tower of Pisa is a campanile. This is an Italian word which refers to a freestanding belltower — freestanding meaning that it is unconnected to its church.

Campaniles are common in Italian architecture, as at St Mark's in Venice.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa is a campanile. This is an Italian word which refers to a freestanding belltower — freestanding meaning that it is unconnected to its church.

Campaniles are common in Italian architecture, as at St Mark's in Venice.

Whereas the bells of Lincoln Cathedral, for example, are in that colossal tower soaring up from its nave, those of the Florence Duomo are in "Giotto's Campanile", just to the side of it.

Here you can see two of the seven bells of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, right at the very top and open to the Tuscan skies.

They were cast between the 13th and 18th centuries and each have their own names.

They were cast between the 13th and 18th centuries and each have their own names.

But if the Leaning Tower is a campanile, it must be next to a church...

Well, unless you have visited yourself, you probably won't know that the Leaning Tower of Pisa stands (or reclines?) beside a vast and beautiful cathedral on a broad green square in the heart of the city.

Well, unless you have visited yourself, you probably won't know that the Leaning Tower of Pisa stands (or reclines?) beside a vast and beautiful cathedral on a broad green square in the heart of the city.

This is the cathedral for which the Leaning Tower's bells are tolled — the Cattedrale Metropolitana Primaziale di Santa Maria Assunta.

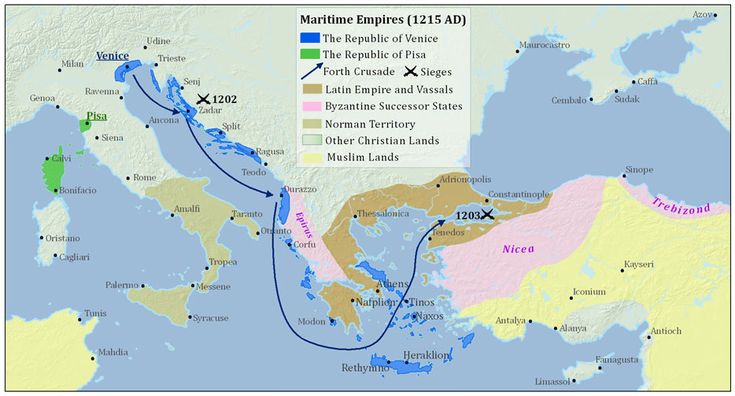

It was built when Pisa was a wealthy and powerful maritime republic directing merchant and naval fleets all across the Mediterranean.

It was built when Pisa was a wealthy and powerful maritime republic directing merchant and naval fleets all across the Mediterranean.

It was the gold from Pisa's trade and conquest that paid for the construction of her grand cathedral, which began in the 11th century.

So why is the tower leaning? Because its foundations gave way... but there's more to the story than that.

See, construction started in 1173 under Diotisalvi and took 199 years. And it was during the construction process that the tower's foundations first shifted.

See, construction started in 1173 under Diotisalvi and took 199 years. And it was during the construction process that the tower's foundations first shifted.

But the architects, masons, and engineers ploughed on and devised several ingenious solutions to ensure that the tower, even if slanted, would be structurally sound.

As the tower grew in height they built the walls of each floor taller on one side than the other.

As the tower grew in height they built the walls of each floor taller on one side than the other.

They also made sure to unevenly distribute the weight of its construction materials so that, even if the tower looks off-kilter, its centre of gravity would be more or less over the base — so it wouldn't fall down.

And, 800 years later, it is still standing.

And, 800 years later, it is still standing.

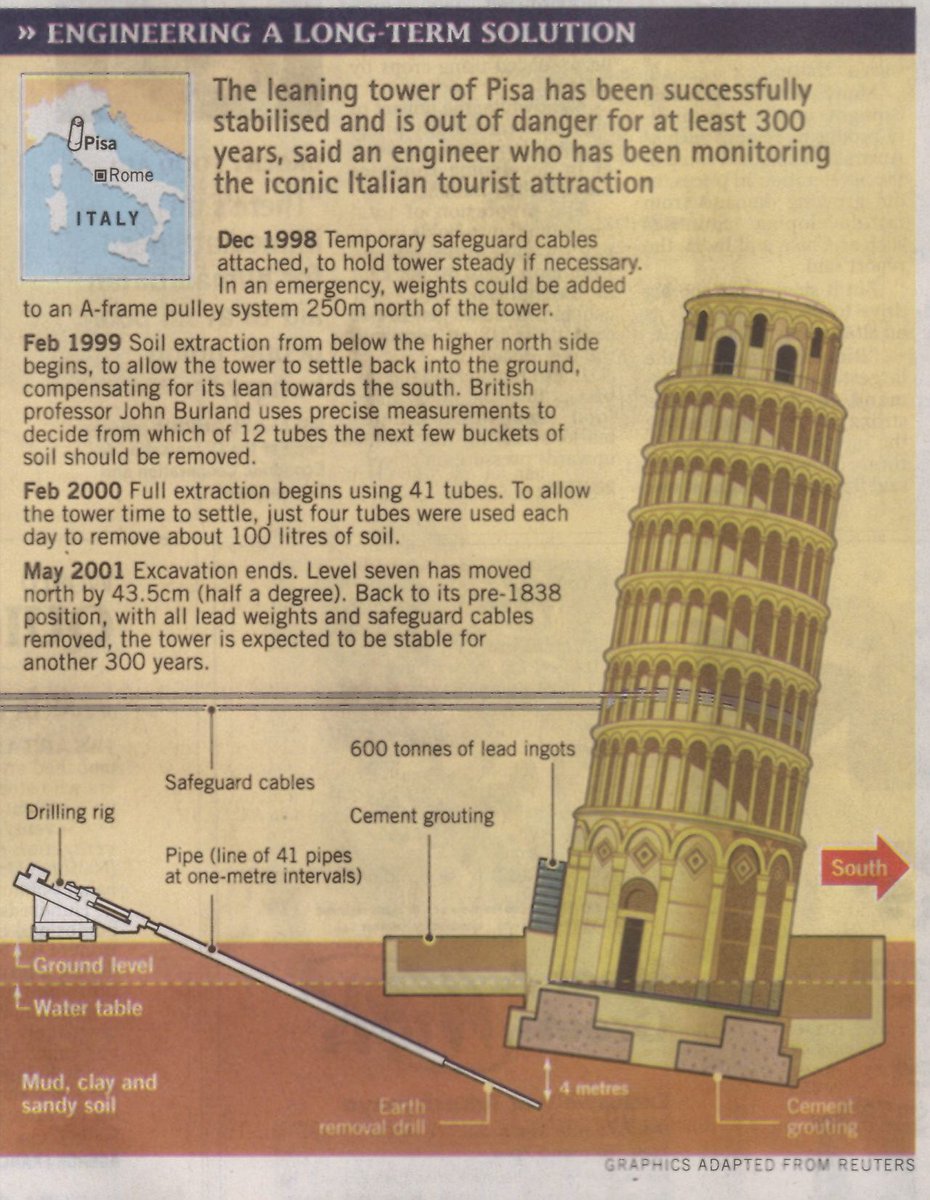

Albeit with some help from stabilisation projects over the years, most recently in the 1990s.

It might have been possible to make the tower completely vertical, but that would have damaged Pisa's tourism industry; thus they decided to maintain its lean.

It might have been possible to make the tower completely vertical, but that would have damaged Pisa's tourism industry; thus they decided to maintain its lean.

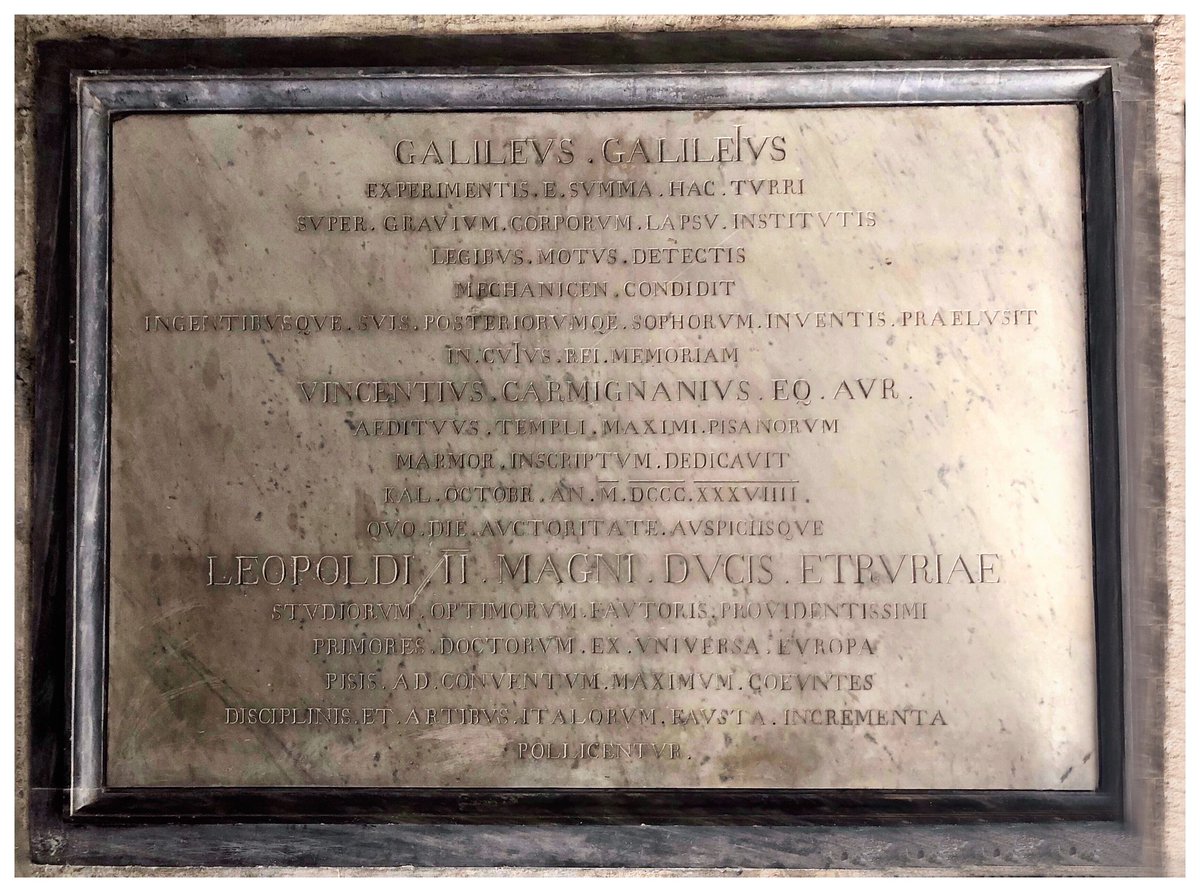

There is an apocryphal story that in 1591 the astronomer Galileo dropped two cannonballs from the top, each of different mass, to prove the Law of Free Fall.

The Tower is nearly 60 metres tall, after all.

And, apocryphal or not, a plaque commemorates his experiment.

The Tower is nearly 60 metres tall, after all.

And, apocryphal or not, a plaque commemorates his experiment.

But the Leaning Tower of Pisa, regardless of its legendary leaning, would still be famous as a masterpiece of Romanesque Architecture.

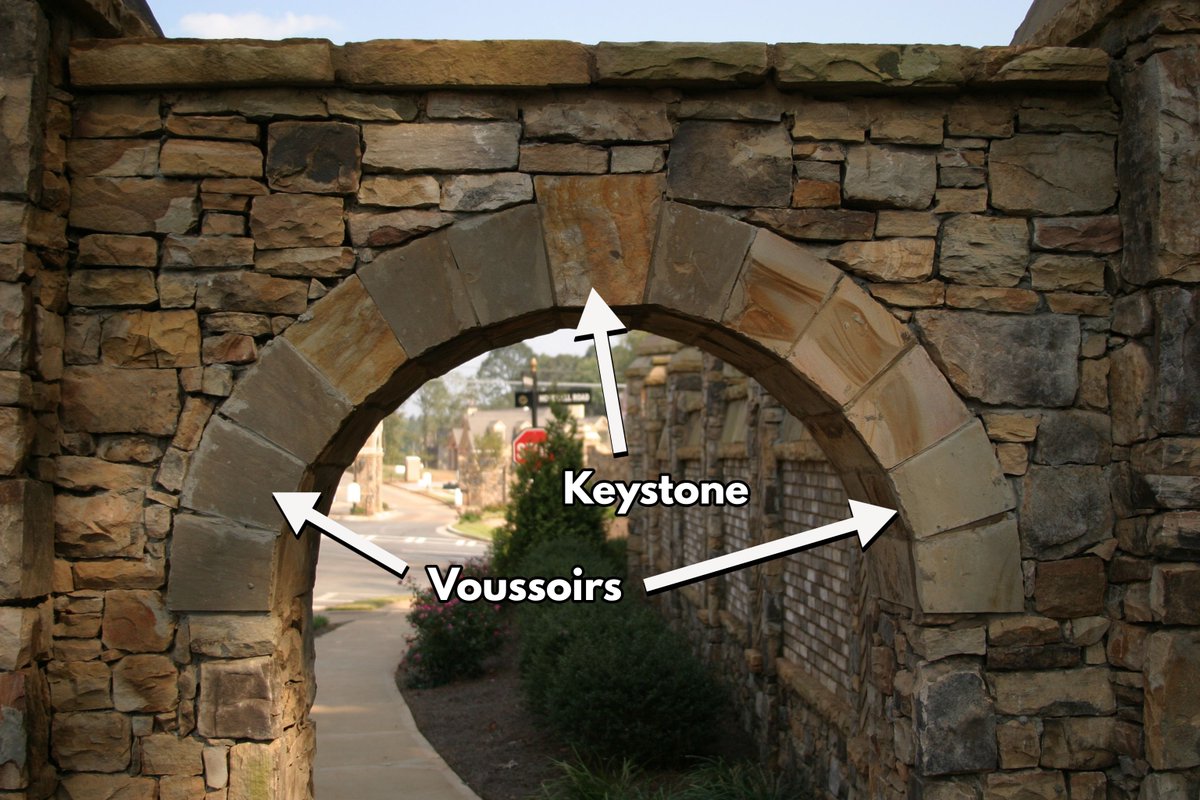

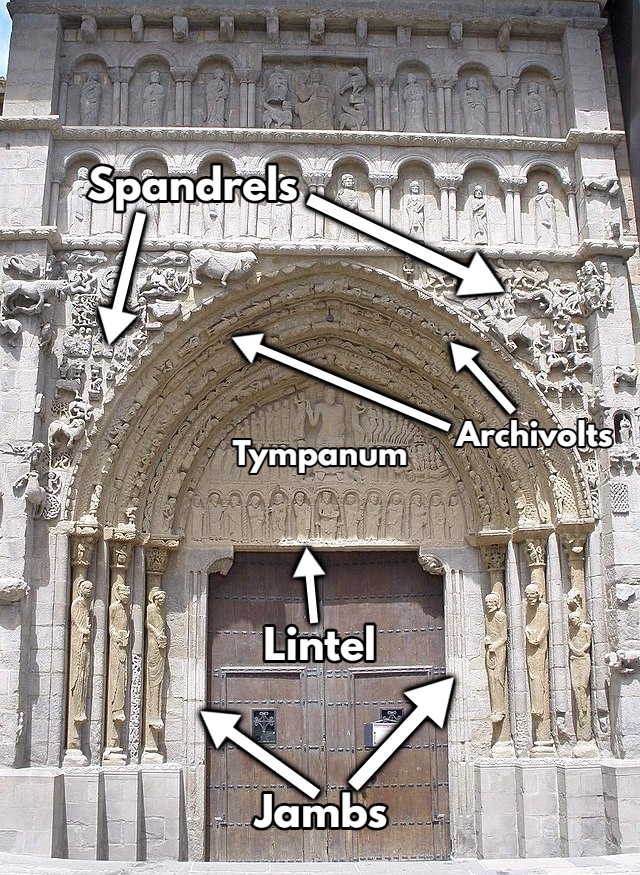

This was the style that preceded the Gothic: rounded arches, small windows, arcades, and a sense of robust, almost monolithic proportion.

This was the style that preceded the Gothic: rounded arches, small windows, arcades, and a sense of robust, almost monolithic proportion.

Row after row of round-arched arcades carved from glittering limestone and snow-white marble, each decorated with an endless variety of capitals, whether flowers or hideous beasts, typical of Romanesque architecture.

It is simply, lean or no lean, a beautiful and unusual tower.

It is simply, lean or no lean, a beautiful and unusual tower.

We can say the same of Pisa Cathedral; its striking facade, a four-tiered cacophony of colonnades, is almost entirely unique.

Indeed, the "Pisan Romanesque" is considered its own style; this is Romanesque Architecture at its most delicate and most exuberant.

Indeed, the "Pisan Romanesque" is considered its own style; this is Romanesque Architecture at its most delicate and most exuberant.

Not to mention the interior of the cathedral, with its pulpit and bronze doors. This is a place filled with masterpieces of art from the Romanesque through the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque.

On the other side of the cathedral is the Baptistery, a splendid building in its own right and — notice the gabled arcades — a masterpiece of Italian Gothic, which was related to but distinct from Northern European Gothic.

The three together are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The three together are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa is a marvellous building regardless of its famous tilt, a monument to the zenith of the Pisan Republic, when it was one of Europe's richest and most important cities, and a testament to the beauty of Romanesque Architecture.

And it is still standing...

And it is still standing...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh