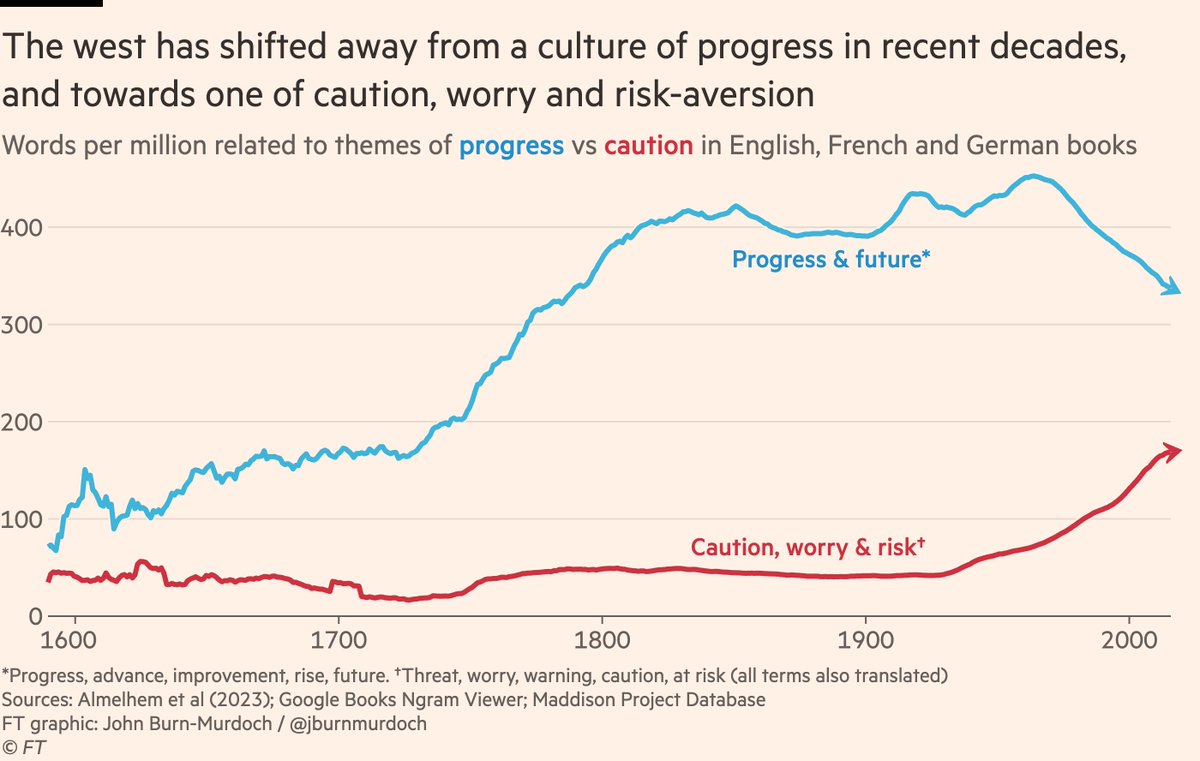

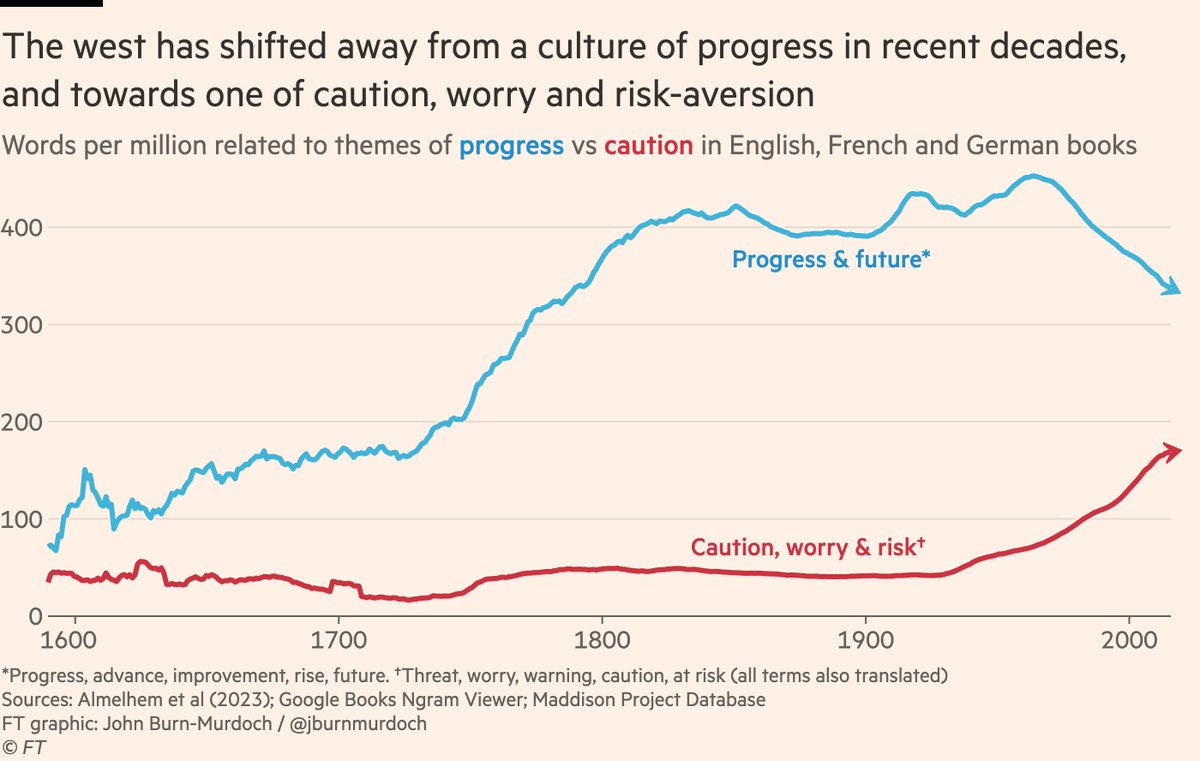

NEW: analysis of millions of books published over the centuries suggests western society is shifting away from a culture of progress, and towards one of caution, worry and risk-aversion.

I think this is one of the most important challenges facing us today.

I think this is one of the most important challenges facing us today.

My column this week explores how language and culture have historically played under-rated roles in human progress, and what that means for our present and future

But let’s get into the details:ft.com/content/e57741…

But let’s get into the details:ft.com/content/e57741…

The industrial revolution was one of the most important events in human history.

Technological breakthroughs kicked economic output off its centuries-long low plateau and sent living standards soaring. Yet there’s still disagreement over why it took off when and where it did.

Technological breakthroughs kicked economic output off its centuries-long low plateau and sent living standards soaring. Yet there’s still disagreement over why it took off when and where it did.

One of the most compelling arguments comes from US economic historian Robert Allen, who argues that high wages and low energy costs in Britain created strong incentives to substitute energy and capital for labour and to mechanise manufacturing processes cepr.org/voxeu/columns/…

Some including @DAcemogluMIT place a greater emphasis on the role of Britain’s institutions, while others argue that ideas simply emerged as a result of increasing interactions among growing and densifying populations.

But another theory comes from Joel Mokyr, who argues culture was key. British thinkers like Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton championed a progress-oriented worldview, centred on the idea that science and experimentation were key to increasing human wellbeing imf.org/external/pubs/…

While persuasive, Mokyr’s theory has until recently been only that: a theory.

But a fascinating paper published last month puts some evidence behind the argument

But a fascinating paper published last month puts some evidence behind the argument

https://twitter.com/jaredcrubin/status/1737095261875277833

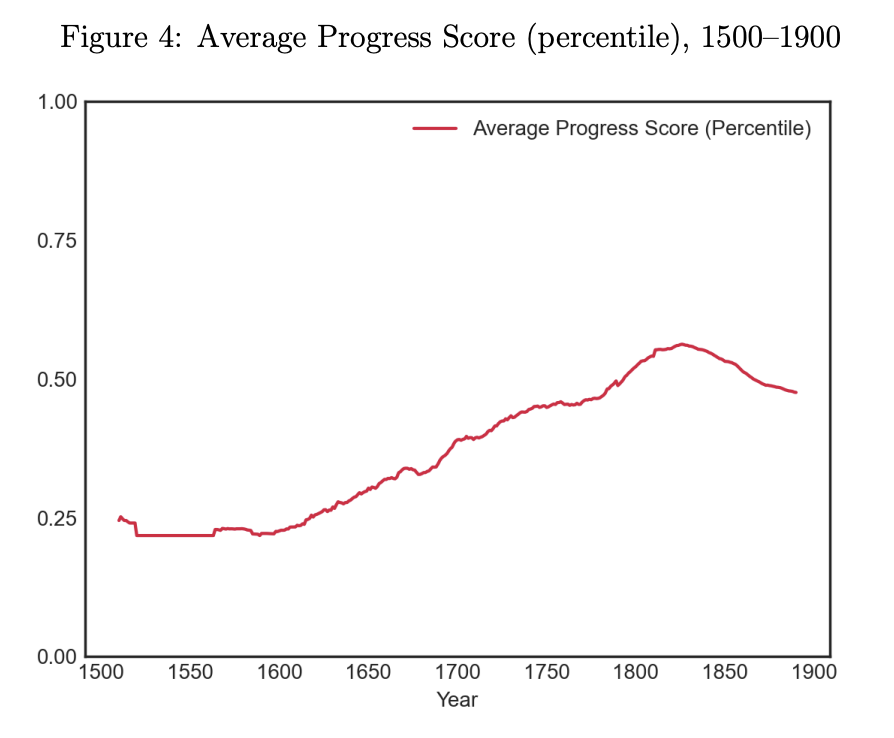

The researchers analysed the contents of 173,031 books printed in England between 1500 and 1900, tracking how the frequency of different terms changed over time, which they use as a proxy for the cultural themes of the day.

They found a marked rise in terms related to progress and innovation starting in the 17th century, supporting the idea that “a cultural evolution in attitudes towards the potential of science accounts in some part for the British industrial revolution and its economic take-off”.

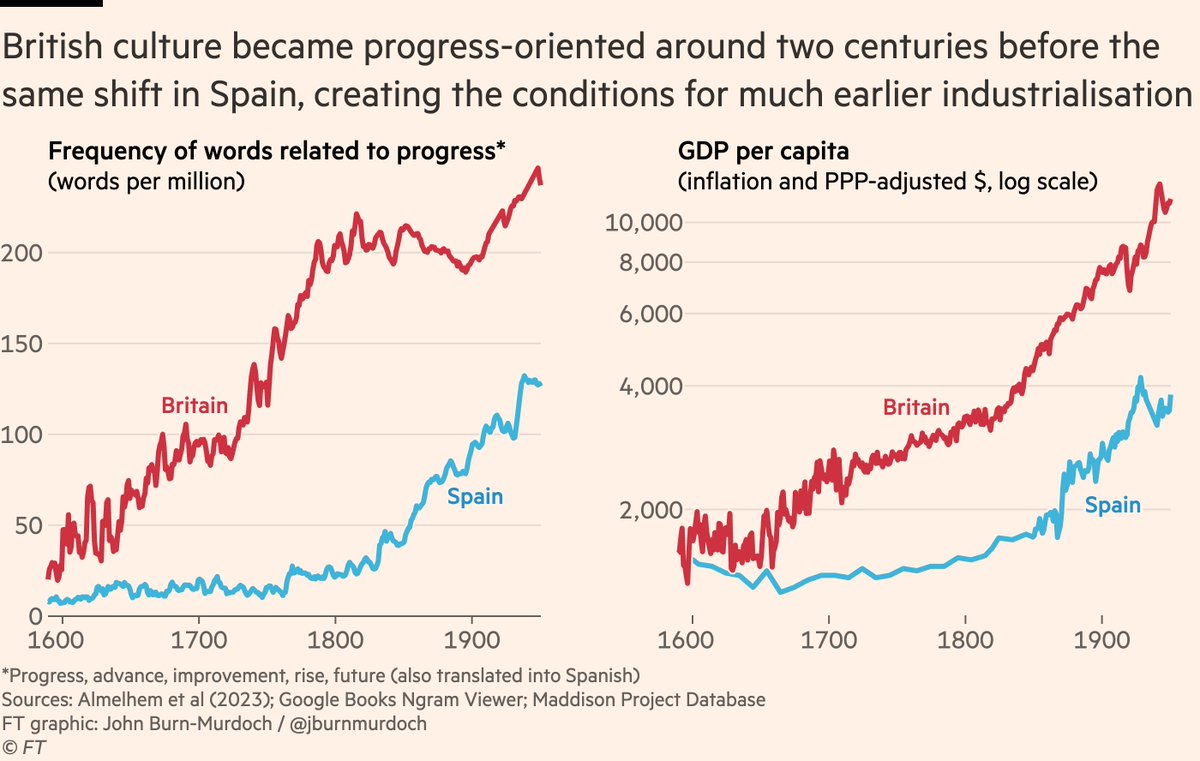

But we can go further: take two countries that were similarly prosperous before the industrial revolution but then diverged: Britain & Spain. Britain underwent the reformation and adopted a culture of using science & experimentation to increase wellbeing. Spain went the other way

What happened next?

The countries’ economic trajectories followed suit.

Britain’s adoption of a culture of progress, science and experimentation was followed by industrialisation. Spain was 200 years later in adopting a similar culture, and 200 years later to industrialise

The countries’ economic trajectories followed suit.

Britain’s adoption of a culture of progress, science and experimentation was followed by industrialisation. Spain was 200 years later in adopting a similar culture, and 200 years later to industrialise

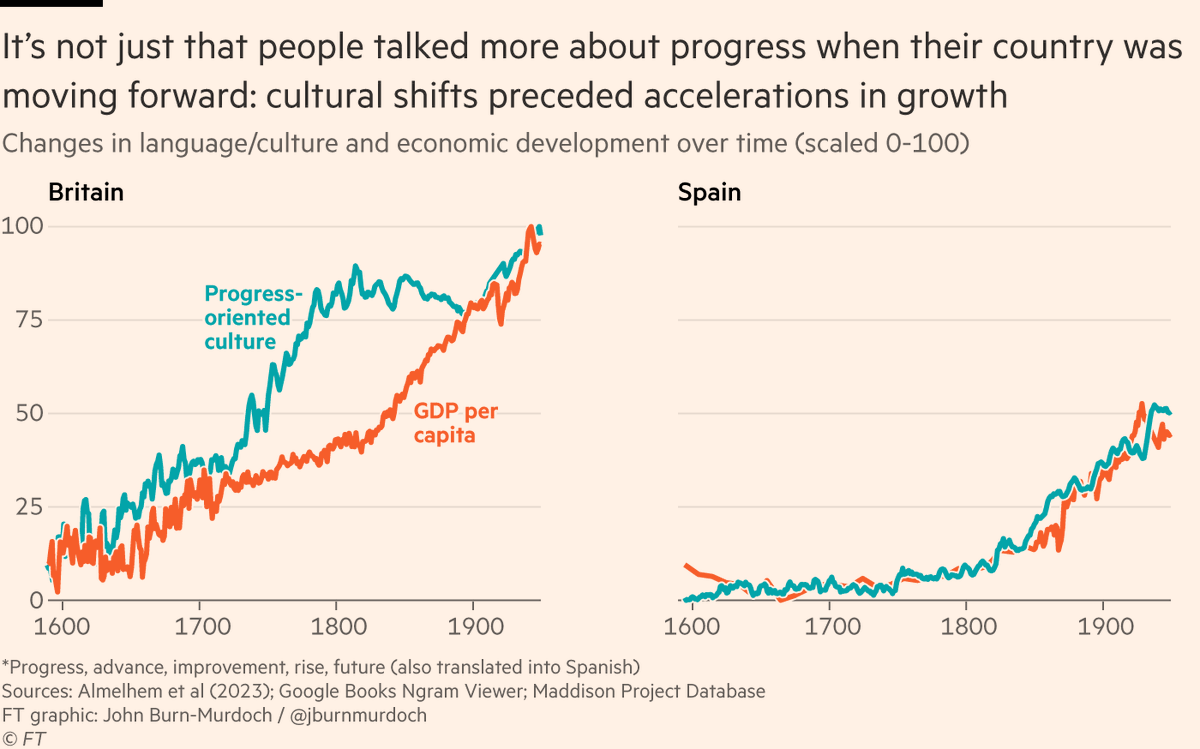

And NB it’s not just that people write more about progress when their country is progressing. Britain’s cultural shift preceded its economic acceleration, as did Spain’s

This is a crucial point:

Language — particularly in books — doesn’t just describe the world as it is, it describes the world as it could be. Writing about how to progress to a better future can make that better future more likely. Writing about worries can create a worried world

Language — particularly in books — doesn’t just describe the world as it is, it describes the world as it could be. Writing about how to progress to a better future can make that better future more likely. Writing about worries can create a worried world

This brings us to the present day, and that striking pattern:

A culture of progress made the west, but over recent decades western culture has been moving away from values of progress and betterment.

In their place, a culture of caution, worry and risk-aversion is on the rise.

A culture of progress made the west, but over recent decades western culture has been moving away from values of progress and betterment.

In their place, a culture of caution, worry and risk-aversion is on the rise.

This explains a lot of recent negative trends.

To take one narrow example, in a society based around ideals of progress and abundance, things get built.

In a society preoccupied with downsides, things get blocked.

Increasingly our society is the latter

To take one narrow example, in a society based around ideals of progress and abundance, things get built.

In a society preoccupied with downsides, things get blocked.

Increasingly our society is the latter

Here, @ruxandrateslo makes a persuasive argument that the growing scepticism of technology and the broader rise in zero-sum thinking is one of the defining ideological challenges of our time writingruxandrabio.com/p/ideas-matter…

I tend to agree. A zero-sum world is a more worried world, and as well as obstructing progress, these views are often associated with populism, nativism and conspiracy theories. Here’s an earlier thread that gets deeper into that

https://twitter.com/jburnmurdoch/status/1705177762305114599

To be clear, some people take a different view.

Many look at the world around them and say that a rebalancing of priorities from perpetual progress to caution is no bad thing.

But I think this would be a big mistake.

Many look at the world around them and say that a rebalancing of priorities from perpetual progress to caution is no bad thing.

But I think this would be a big mistake.

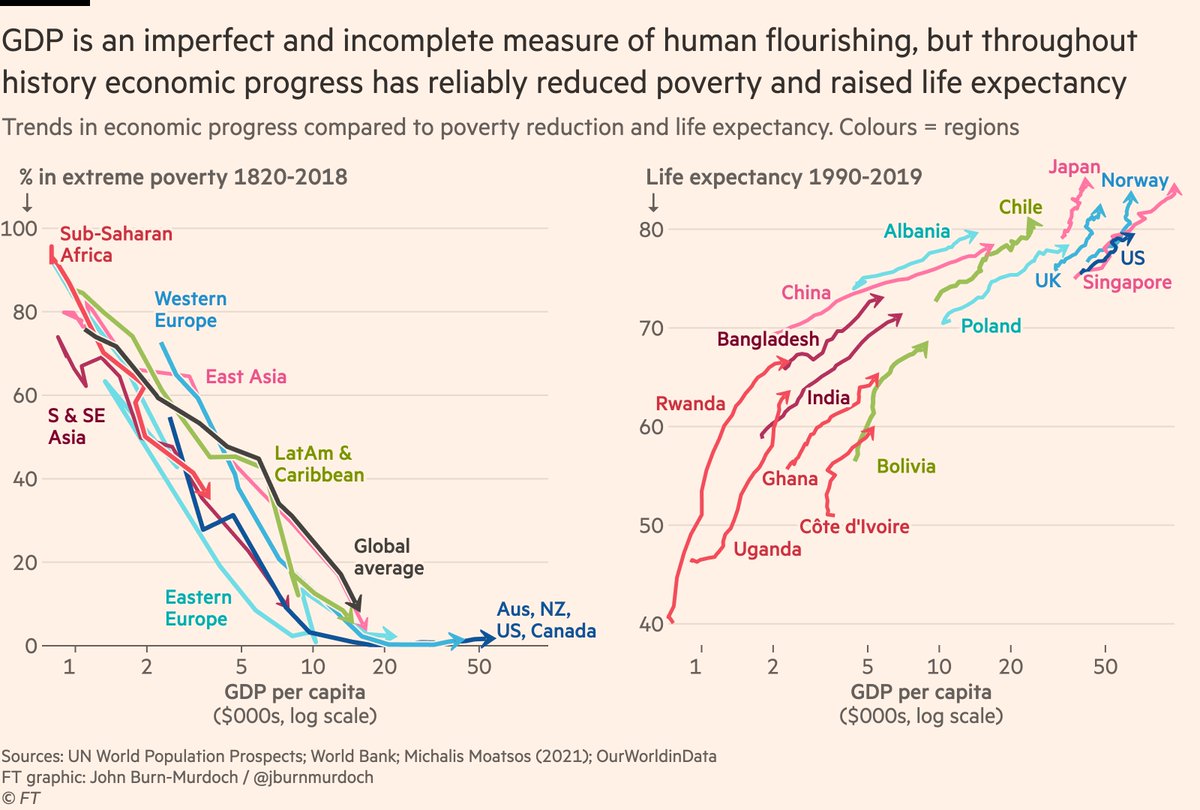

As well as GDP, the drive for progress brought us modern medicine, longer and healthier lives, plentiful food supplies, dramatic reductions in poverty, and more and cheaper renewable energy. The challenges facing the modern world will be solved by more focus on progress, not less

We know what a society that denigrates progress looks like. The pre-industrial world was one of mass conflict, exploitation and suffering.

If we are to avoid backsliding, advocates for innovation, growth and abundance must win the economic culture war.

If we are to avoid backsliding, advocates for innovation, growth and abundance must win the economic culture war.

Here’s the column again in full:

Culture and language are often overlooked in discussions about economics and development, but I think this is a fascinating and vital topic.

Kudos to @jaredcrubin and co for a brilliant and thought-provoking paper.ft.com/content/e57741…

Culture and language are often overlooked in discussions about economics and development, but I think this is a fascinating and vital topic.

Kudos to @jaredcrubin and co for a brilliant and thought-provoking paper.ft.com/content/e57741…

Common response in replies is “but the world is a lot scarier now”.

I think “scarier” is the key. The world may feel scarier, but is it actually more dangerous in any objective way?

Scariness depends as much (if not more!) on how facts are communicated as on what the facts are.

I think “scarier” is the key. The world may feel scarier, but is it actually more dangerous in any objective way?

Scariness depends as much (if not more!) on how facts are communicated as on what the facts are.

Is the world more dangerous now than it was in the late 1930s? The Second World War? Cuban Missile Crisis?

Rates of conflict and violent crime have plummeted. All measures of poverty and hardship are way down. Every year we invent and deploy new means of tackling climate change.

Rates of conflict and violent crime have plummeted. All measures of poverty and hardship are way down. Every year we invent and deploy new means of tackling climate change.

I’m with @_HannahRitchie and @MaxCRoser on this one. There are many *many* problems in the world today.

But the world is a much better place today than at ~any time in the past.

But the world is a much better place today than at ~any time in the past.

https://twitter.com/_hannahritchie/status/1742127665908207707

imo what’s changed is:

• We hear more scary stories these days

• In particular we hear more scary stories about things outside our individual control (these are more anxiety-inducing)

• *Because our lives are less grim* we have more time to think about distant scariness

• We hear more scary stories these days

• In particular we hear more scary stories about things outside our individual control (these are more anxiety-inducing)

• *Because our lives are less grim* we have more time to think about distant scariness

To be clear, I think the overwhelming majority of people telling scary stories or worrying about worrying things are entirely well-intentioned! They care deeply about the people affected by these problems.

But out of the two ways of framing problems — as challenges we must rise up to, or as woes that we must wring our hands over or impending doom — I think we’re forgetting how to do the former, and this is making it harder to solve those problems.

Discuss!

Discuss!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh