As the waters recede on another monster flood, thousands of homes and businesses along the Severn and Wye remain dry thanks to flood defences.

They work.

But they’re not the answer to future flooding and are creating a false sense of security.

A (long!) 🧵

They work.

But they’re not the answer to future flooding and are creating a false sense of security.

A (long!) 🧵

Since the devastating floods of 1998 and 2000 this area has been a test bed for novel flood protection methods and has also received many millions of £ to build defences.

Remember Prescott in his wellies, the flood sausage, prototype A frames?

Remember Prescott in his wellies, the flood sausage, prototype A frames?

Many communities along the Severn and Wye now have operational flood defences.

And they work.

Thousands of homes and businesses are dry today because they’re there.

If this same flood had happened in 2000 it would have been carnage.

And they work.

Thousands of homes and businesses are dry today because they’re there.

If this same flood had happened in 2000 it would have been carnage.

Take Upton for example, dubbed the most flooded town in the UK.

Defences built in 2011 after the catastrophic floods of 2007 at a cost of £4.5m have now protected the town over 50 times.

Last week flood water would have been chest high in the waterside buildings.

Defences built in 2011 after the catastrophic floods of 2007 at a cost of £4.5m have now protected the town over 50 times.

Last week flood water would have been chest high in the waterside buildings.

Or Bewdley where £11m was spent in 2006 defending the west side of the town, protecting 200 homes and businesses.

The demountable barriers have done the job on dozens of occasions now keeping Bewdley open and dry even during big floods.

The demountable barriers have done the job on dozens of occasions now keeping Bewdley open and dry even during big floods.

So far, so good.

And it is undoubtedly a success story.

But.

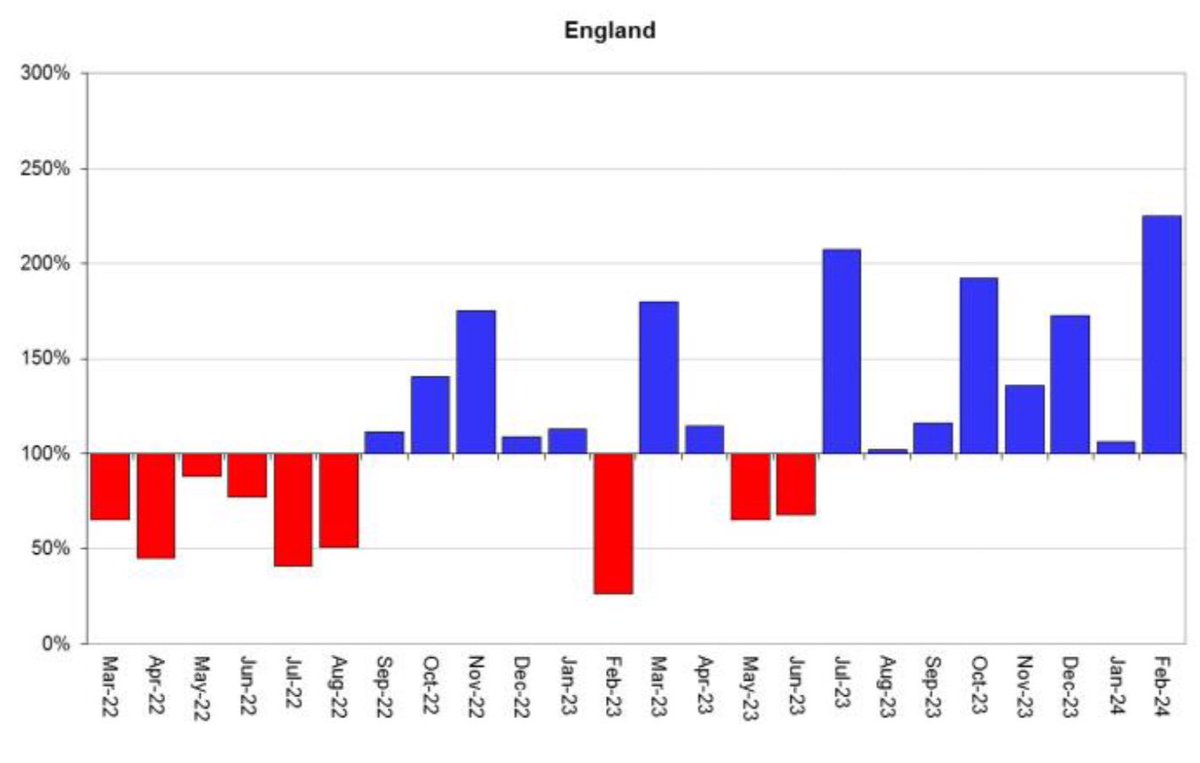

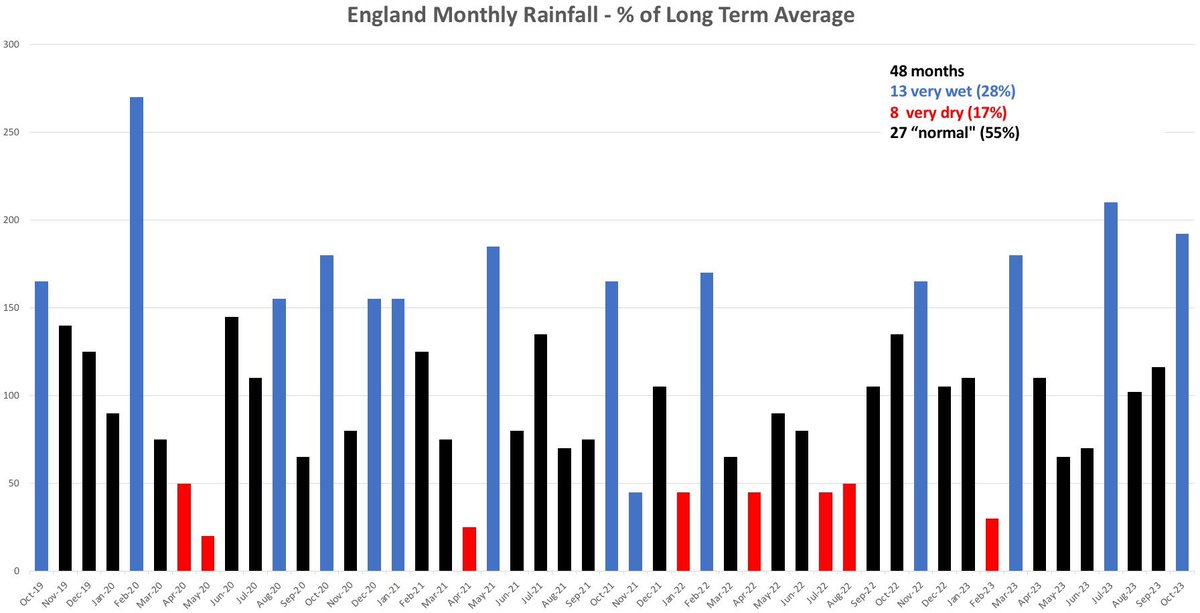

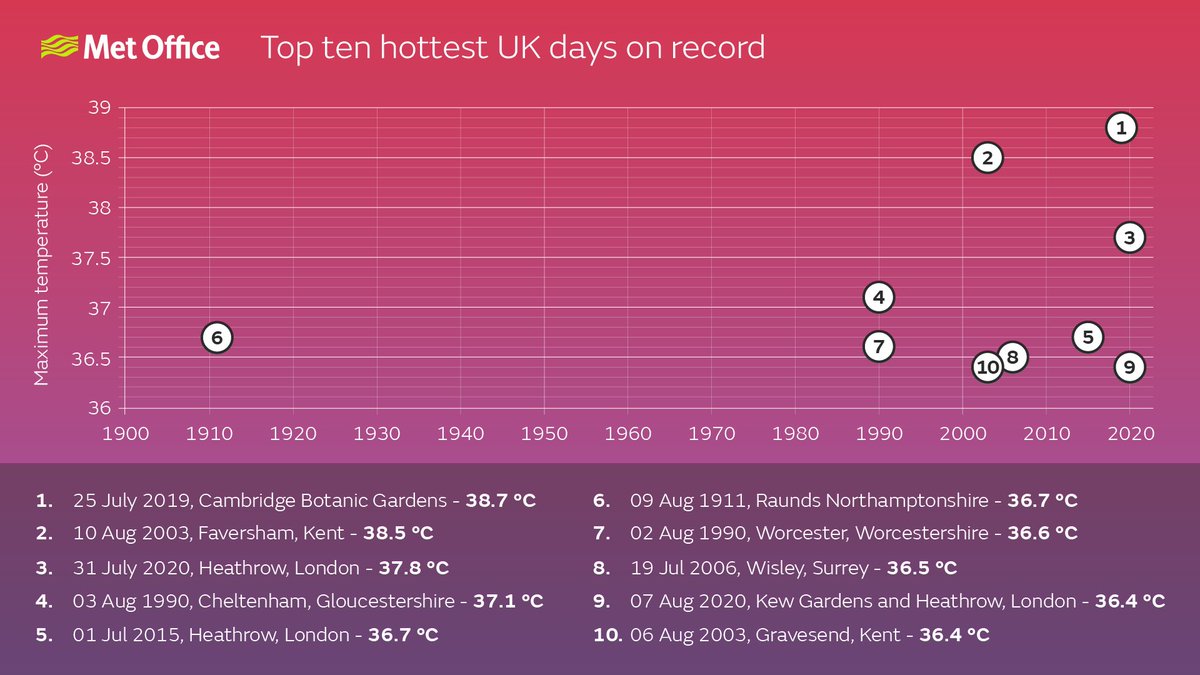

Floods are getting bigger due to a rapidly changing climate.

During the floods of 2020 every flood defence on the Severn & Wye was within 0.5-1.0m of overtopping.

It will have been a similar story last week.

And it is undoubtedly a success story.

But.

Floods are getting bigger due to a rapidly changing climate.

During the floods of 2020 every flood defence on the Severn & Wye was within 0.5-1.0m of overtopping.

It will have been a similar story last week.

Traditionally flood defences were built to withstand a 1 in 100 year flood.

This has since been increased to allow extra for climate change - around 1 in 120-140 year.

But as you can imagine these figures are pretty meaningless today.

This has since been increased to allow extra for climate change - around 1 in 120-140 year.

But as you can imagine these figures are pretty meaningless today.

Recent years have brought a mind boggling series of extremes.

The 2009 Cumbria floods were calculated as a 1 in 500 to 1 in 2000 year event around Cockermouth.

The hydrograph is scarcely believable when assessed against previous floods.

The 2009 Cumbria floods were calculated as a 1 in 500 to 1 in 2000 year event around Cockermouth.

The hydrograph is scarcely believable when assessed against previous floods.

The 2015 floods in the north of England resulted in a number of rivers seeing levels that you would only expect to see once in 200 years according to historical precedent.

February 2020 brought record breaking river levels across the UK, including the Lugg and Wye where return periods were between 150 and 550 years.

And Storm Babet in October last year brought extreme levels and flooding to eastern parts of the UK.

The River Esk at Brechin and the Rother in Sheffield recording extreme levels and severe flooding.

The River Esk at Brechin and the Rother in Sheffield recording extreme levels and severe flooding.

It’s not surprising then that flood defences built to cope with 1 in 100 year floods are struggling.

Keswick defences were built in 2012 were overtopped by a metre in 2015.

Brechin flood defences completed in 2015 to defend against a 1 in 200 year flood were overtopped in 2023

Keswick defences were built in 2012 were overtopped by a metre in 2015.

Brechin flood defences completed in 2015 to defend against a 1 in 200 year flood were overtopped in 2023

Locally Powick flood defences were overtopped in 2020 and Beales Corner temporary defences overtopped or failed on 3 occasions.

Important to note though that these defences have less than 1 in 100 year standards of protection.

Important to note though that these defences have less than 1 in 100 year standards of protection.

This doesn’t mean the flood defences have failed.

They’ve done what they were designed to do.

Protect to a certain size of flood.

When you get a bigger one it goes over the top or round the edge.

They’ve done what they were designed to do.

Protect to a certain size of flood.

When you get a bigger one it goes over the top or round the edge.

And now the real kicker!

Every prediction is showing very significant increases in peak river flows and levels in the near future due to climate change.

You can check out your local rivers here eip.ceh.ac.uk/hydrology/cc-i…

Every prediction is showing very significant increases in peak river flows and levels in the near future due to climate change.

You can check out your local rivers here eip.ceh.ac.uk/hydrology/cc-i…

As an example, on the lower River Severn where levels are currently dropping from near record highs, it’s predicted that flood peaks will rise by 15-25% through the next 20 years.

The nearby River Teme is even more watering with peaks predicted to increase by 20-30%

The nearby River Teme is even more watering with peaks predicted to increase by 20-30%

So coming full circle, a big flood on the Severn, like the one we’ve just seen, or 2020 or 2021, is getting quite close to the capability of flood defences.

And we expect significant increases in flood peaks due to climate change in the very near future.

And we expect significant increases in flood peaks due to climate change in the very near future.

What to do?

We can’t engineer our way out. Raising existing defences won’t be technically, financially or environmentally possible.

Designing future defences to a much higher standard of protection would make them many times more expensive & physically huge.

We can’t engineer our way out. Raising existing defences won’t be technically, financially or environmentally possible.

Designing future defences to a much higher standard of protection would make them many times more expensive & physically huge.

Catchment scale attenuation provides some hope for the future. But is complex, requiring joined up policy & funding.

Reducing flood peaks by slowing runoff with multiple interventions.

Before anyone asks wide-scale dredging would make things much worse (here at least).

Reducing flood peaks by slowing runoff with multiple interventions.

Before anyone asks wide-scale dredging would make things much worse (here at least).

Finally, if you live behind a flood defence, don’t be complacent.

They will protect you from most floods. But not all.

You should expect to be flooded in future.

Have a plan for when it happens.

Ends gov.uk/government/pub…

They will protect you from most floods. But not all.

You should expect to be flooded in future.

Have a plan for when it happens.

Ends gov.uk/government/pub…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh