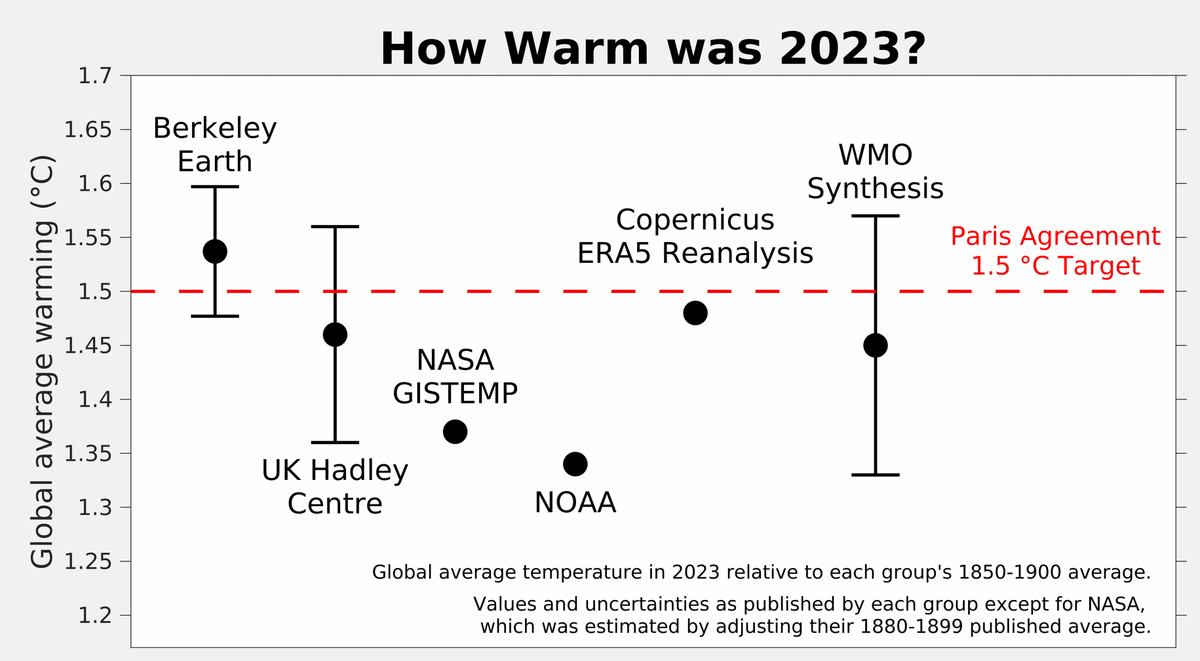

How warm was 2023?

It was the first year that any of the major temperature analysis groups exceeded 1.5 °C above their "preindustrial" 1850-1900 average, thus touching the Paris Agreement limit.

It was the first year that any of the major temperature analysis groups exceeded 1.5 °C above their "preindustrial" 1850-1900 average, thus touching the Paris Agreement limit.

Under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change countries agreed to "pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels".

The exact definition of how that would be measured is intentionally vaguely, but most agree it refers to a multi-year average.

The exact definition of how that would be measured is intentionally vaguely, but most agree it refers to a multi-year average.

A single year above 1.5°C won't, by itself, be a breach of the limit, as the focus is on the long-term average.

However, reaching 1.5 °C for the first time shows how little time remains.

However, reaching 1.5 °C for the first time shows how little time remains.

However, why do different analysis groups get slightly different answers for how much warming has already occurred?

If one focuses on a modern frame of reference, then all of the groups show similar trends.

Aligned here to each group's 1981-2010 average.

If one focuses on a modern frame of reference, then all of the groups show similar trends.

Aligned here to each group's 1981-2010 average.

However, problems arise when trying to compare warming since the 19th century.

Sparser global coverage and systematic biases in early instruments & methods make the early period more uncertain.

That uncertainty adds spread to the modern values when using a 1850-1900 reference.

Sparser global coverage and systematic biases in early instruments & methods make the early period more uncertain.

That uncertainty adds spread to the modern values when using a 1850-1900 reference.

The biggest source of uncertainty in the long-term change comes from the oceans.

Only two major ocean instrumental analyses exist HadSST & ERSST), and they do not agree!

Groups using HadSST (Hadley & Berkeley Earth) thus have more warming that those using ERSST (NASA & NOAA).

Only two major ocean instrumental analyses exist HadSST & ERSST), and they do not agree!

Groups using HadSST (Hadley & Berkeley Earth) thus have more warming that those using ERSST (NASA & NOAA).

The main reason for disagreement between ERSST and HadSST comes down primarily to bias corrections.

Over time the ways that ocean temperatures have been measured evolved.

Originally, buckets were lowered into the sea, hauled up, and measured with thermometers on deck.

Over time the ways that ocean temperatures have been measured evolved.

Originally, buckets were lowered into the sea, hauled up, and measured with thermometers on deck.

Wooden buckets were replaced with waterproof fabric sacks, and later rubber buckets.

Rubber buckets gave way to measuring engine intake water, or checking the outer hull temperature.

Those were replaced with automated buoys.

Etc, etc.

Rubber buckets gave way to measuring engine intake water, or checking the outer hull temperature.

Those were replaced with automated buoys.

Etc, etc.

Every evolution of how ocean temperatures were measured has added small systematic biases.

For example, engine intake water typically came from several meters below the surface, and was often a few 0.1 °C colder than the buckets hauled from the ocean's surface.

For example, engine intake water typically came from several meters below the surface, and was often a few 0.1 °C colder than the buckets hauled from the ocean's surface.

Correcting for the systematic changes in how oceans have been measured is the largest challenge in ocean analysis.

And disagreements about bias corrections are the main difference between ERSST & HadSST, and hence overall uncertainty in global warming since preindustrial.

And disagreements about bias corrections are the main difference between ERSST & HadSST, and hence overall uncertainty in global warming since preindustrial.

In recent years, there have been renewed calls for more research focus on understanding the uncertainties and biases in ocean temperature histories, but that work has yet to be done.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh