This is the Lonely Castle, a 2,000 year old tomb in Hegra, an ancient city in Saudi Arabia.

It's a perfect example of "rock-cut architecture" — when you carve a whole building out of stone.

And there are plenty more places like it, all around the world...

It's a perfect example of "rock-cut architecture" — when you carve a whole building out of stone.

And there are plenty more places like it, all around the world...

There is something instinctively awe-inspiring about rock-cut architecture.

To carve a building out the living stone of the earth feels elemental.

Nothing artificial here, only solid rock. Everything is part of one great whole. Monolithic, ancient, mysterious.

To carve a building out the living stone of the earth feels elemental.

Nothing artificial here, only solid rock. Everything is part of one great whole. Monolithic, ancient, mysterious.

It's also a technical marvel.

This is construction in reverse — rather than building up bit by bit you are removing parts, taking away rather than adding.

Just as a sculpture is carved from a single block, this is architecture-as-sculpture... sculpture you can walk inside.

This is construction in reverse — rather than building up bit by bit you are removing parts, taking away rather than adding.

Just as a sculpture is carved from a single block, this is architecture-as-sculpture... sculpture you can walk inside.

Over the millennia four types of rock-cut architecture have emerged.

First... tombs.

Like these, made in the time the of ancient Kingdom of Lycia over two thousand years ago, in modern-day Turkey, as a rock-cut necropolis for kings and princes.

First... tombs.

Like these, made in the time the of ancient Kingdom of Lycia over two thousand years ago, in modern-day Turkey, as a rock-cut necropolis for kings and princes.

Sometimes carving tombs out of the rock was necessary because of a lack of other durable materials — an advantage of rock-cut architecture is that it will last.

As at Hegra in Saudi Arabia, where the so-called "Lonely Castle" was built by the Nabataeans two thousand years ago.

As at Hegra in Saudi Arabia, where the so-called "Lonely Castle" was built by the Nabataeans two thousand years ago.

What king would not want their tomb to outlast the generations to come?

Like Darius the Great, King of the Persian Empire, whose colossal tomb survives — along with several others — at the rock-cut necropolis of Naqsh-e Rostam in Iran.

This is two and a half thousand years old.

Like Darius the Great, King of the Persian Empire, whose colossal tomb survives — along with several others — at the rock-cut necropolis of Naqsh-e Rostam in Iran.

This is two and a half thousand years old.

The second type of rock-cut architecture is the most common: temples and churches.

Like Lalibela in Ethiopia, where King Gebre Meskel had fourteen churches carved from the hills, connected by tunnels and passages, to recreate his own Jerusalem in the 13th century.

Like Lalibela in Ethiopia, where King Gebre Meskel had fourteen churches carved from the hills, connected by tunnels and passages, to recreate his own Jerusalem in the 13th century.

Christians who lived in Cappadoccia, Turkey — a region with a rich heritage of rock-cut architecture — had little choice but to carve churches for themsleves into its hillsides.

Simple at first, when hiding from Roman persecution, but later on a grander scale.

Simple at first, when hiding from Roman persecution, but later on a grander scale.

The strange thing about many of these rock-cut churches is that they are designed as if they had been built normally.

The same columns and capitals are used, the same vaults and arcades, even though it wasn't necessary.

A peculiar form of architectural skeuomorphism.

The same columns and capitals are used, the same vaults and arcades, even though it wasn't necessary.

A peculiar form of architectural skeuomorphism.

In any case, nowhere has rock-cut architecture been perfected and developed as in India — here there are more rock-cut buildings than anywhere else on earth.

The most famous example is the vast complex at Ellora, a place that defies explanation and fires the imagination.

The most famous example is the vast complex at Ellora, a place that defies explanation and fires the imagination.

But Ellora isn't unique.

India is filled with places like it, whether whole temples with multiple stories cut into mountainsides or large boulders sculpted down and hollowed out.

For centuries it was normal to carve temples from the earth rather than "build" them.

India is filled with places like it, whether whole temples with multiple stories cut into mountainsides or large boulders sculpted down and hollowed out.

For centuries it was normal to carve temples from the earth rather than "build" them.

The Ajanta Caves are another fabulous example — a vast network of cave-temples, monasteries, and shrines, all richly painted and filled with sculpture.

These artists and architects have bequeathed beautiful cultural treasures to posterity.

These artists and architects have bequeathed beautiful cultural treasures to posterity.

Some of the oldest rock-cut architecture in India is the Barabar Caves, dating back to the reign of Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BC.

They feature unusual interiors where the stone has been polished to perfection so that it has a mirror-like surface.

They feature unusual interiors where the stone has been polished to perfection so that it has a mirror-like surface.

The third type of rock-cut architecture is urban — when we carve a place to live, a settlement, into the stone.

Petra is the best example of urban rock-cut architecture, and is indeed the most famous example of rock-cut architecture full stop.

Petra is the best example of urban rock-cut architecture, and is indeed the most famous example of rock-cut architecture full stop.

And for good reason — this is a rock-cut city.

It was created by the Nabataeans, an ancient kingdom who traded and fought with, among others, the Romans.

This was their capital, complete with tombs, temples, a theatre, a water management system, and more.

It was created by the Nabataeans, an ancient kingdom who traded and fought with, among others, the Romans.

This was their capital, complete with tombs, temples, a theatre, a water management system, and more.

Not far away is another Nabataean town usually called "Little Petra".

Though not as large it is still an impressive place, and speaks to the power and sophistication of the Nabataeans.

Here there is a dining room carved into the sandstone... with ancient paintings on the walls.

Though not as large it is still an impressive place, and speaks to the power and sophistication of the Nabataeans.

Here there is a dining room carved into the sandstone... with ancient paintings on the walls.

But not all rock-cut cities are quite so grand.

Cappadoccia, mentioned already, has been home to rock-cut settlements for millennia, partly because of its soft stone.

Here were carved houses of all sizes, castles, churches, and even toilets.

Cappadoccia, mentioned already, has been home to rock-cut settlements for millennia, partly because of its soft stone.

Here were carved houses of all sizes, castles, churches, and even toilets.

The fourth kind of rock-cut architecture is sculpture.

Rather than using a single block of stone... artists carved whole mountainsides instead.

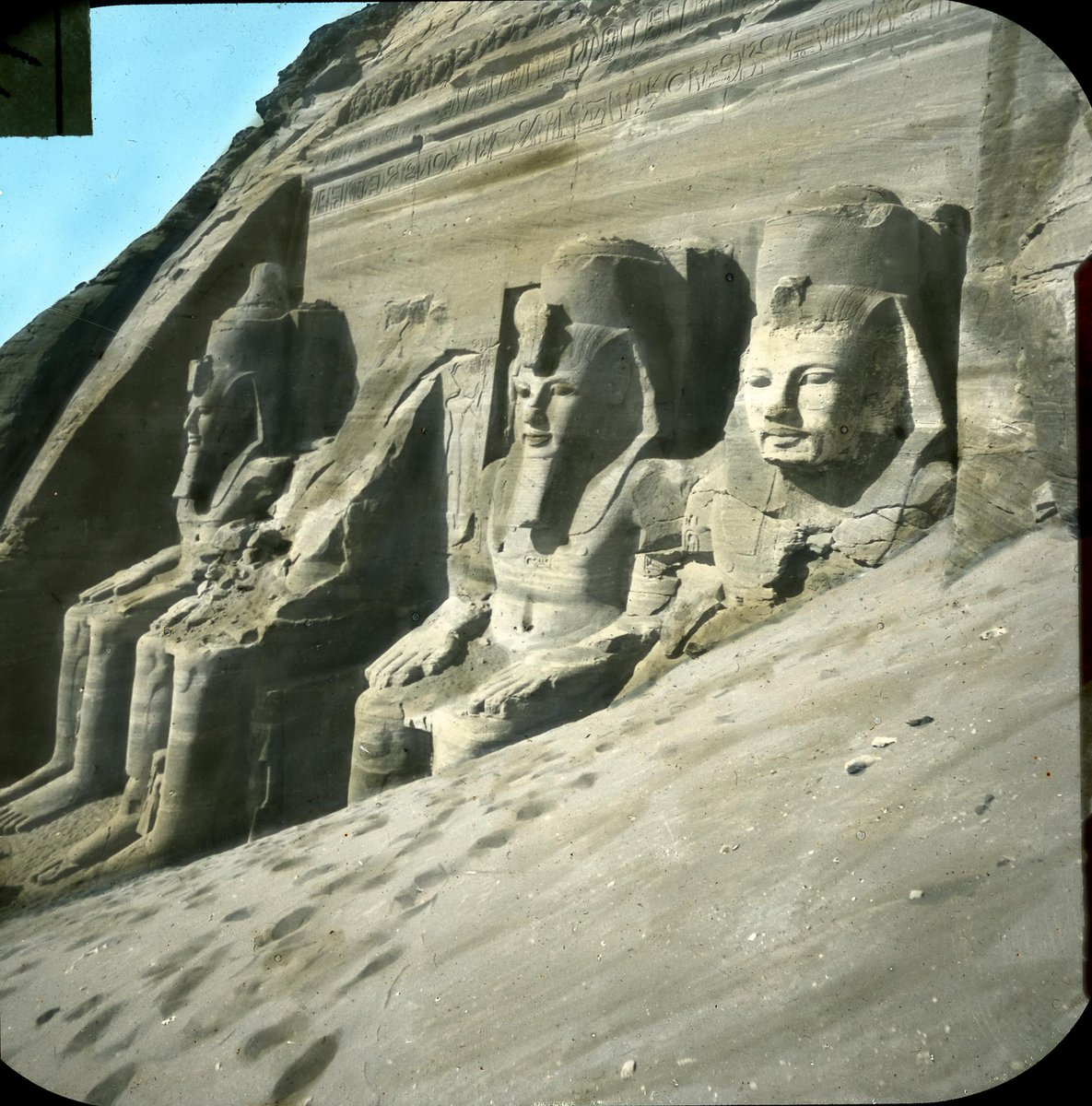

Mount Rushmore is an example, or Abu Simbel in Egypt, made for Ramesses II in 1200 BC, an eternal monument to the mighty.

Rather than using a single block of stone... artists carved whole mountainsides instead.

Mount Rushmore is an example, or Abu Simbel in Egypt, made for Ramesses II in 1200 BC, an eternal monument to the mighty.

Rock-cut sculpture has a particularly rich heritage in China — like the Leshan Buddha, which was the largest statue in the world for one thousand years.

But, even if not quite as large, the rock-cut art of the Longmen Grottos are perhaps more impressive.

The amount of sculpture here (and elsewhere in China, for example at Dazu) is almost incalculably large, all of it varied and exquisitely crafted.

The amount of sculpture here (and elsewhere in China, for example at Dazu) is almost incalculably large, all of it varied and exquisitely crafted.

Of course, the line between rock-cut sculpture and any other form of rock-cut architecture is easily blurred... but is that not the beauty of it?

These are miracles of engineering, design, architecture, and imagination.

These are miracles of engineering, design, architecture, and imagination.

Rock-cut architecture feels like a unique form of building, a category of its own wholly unlike anything else.

These monoliths were time-consuming, expensive and difficult... but they have lasted for millennia and speak to us across that gulf of time.

Wondrous.

These monoliths were time-consuming, expensive and difficult... but they have lasted for millennia and speak to us across that gulf of time.

Wondrous.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh