The Library of Alexandria isn't the only library lost to time.

There was also the "House of Wisdom", built 1,000 years ago in Baghdad when it was the world's largest city.

What did it contain? What happened to it? This is the story of history's other great library...

There was also the "House of Wisdom", built 1,000 years ago in Baghdad when it was the world's largest city.

What did it contain? What happened to it? This is the story of history's other great library...

The world changed in the 7th century.

A new religion emerged in the Arabian Peninsula — Islam — and within a century its followers had conquered half the known-world.

Never before in history had such a vast conquest been carried out so quickly.

A new religion emerged in the Arabian Peninsula — Islam — and within a century its followers had conquered half the known-world.

Never before in history had such a vast conquest been carried out so quickly.

First this colossal state was ruled by the Rashidun Caliphate, which fell in 661 AD and was replaced by the Umayyad Caliphate.

The Umayyads, who ruled from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, chose Damascus in Syria for their capital, at its very centre.

The Umayyads, who ruled from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, chose Damascus in Syria for their capital, at its very centre.

But Umayyad rule did not last — in 750 AD there was a revolution and the Abbasids took control.

In order to consolidate his power the second Abbasid Caliph, al-Mansur, decided to move the capital further east.

And on the banks of the River Tigris he founded a new city: Baghdad.

In order to consolidate his power the second Abbasid Caliph, al-Mansur, decided to move the capital further east.

And on the banks of the River Tigris he founded a new city: Baghdad.

This was the place where civilisation had been born, ever caught in the cultural cross-winds of history — a few miles away lay Babylon, one of the world's most ancient cities.

Also nearby was Ctesiphon, capital of the Sasanian Empire, which had been conquered by the Umayyads.

Also nearby was Ctesiphon, capital of the Sasanian Empire, which had been conquered by the Umayyads.

And this was important, because the Sasanians had a rich, sophisticated, and storied culture with a lineage dating back one thousand years to the rule of Cyrus the Great.

Al-Mansur integrated the Sasanians and their Persian culture into his new Abbasid administration.

Al-Mansur integrated the Sasanians and their Persian culture into his new Abbasid administration.

And al-Mansur had grand plans for this capital.

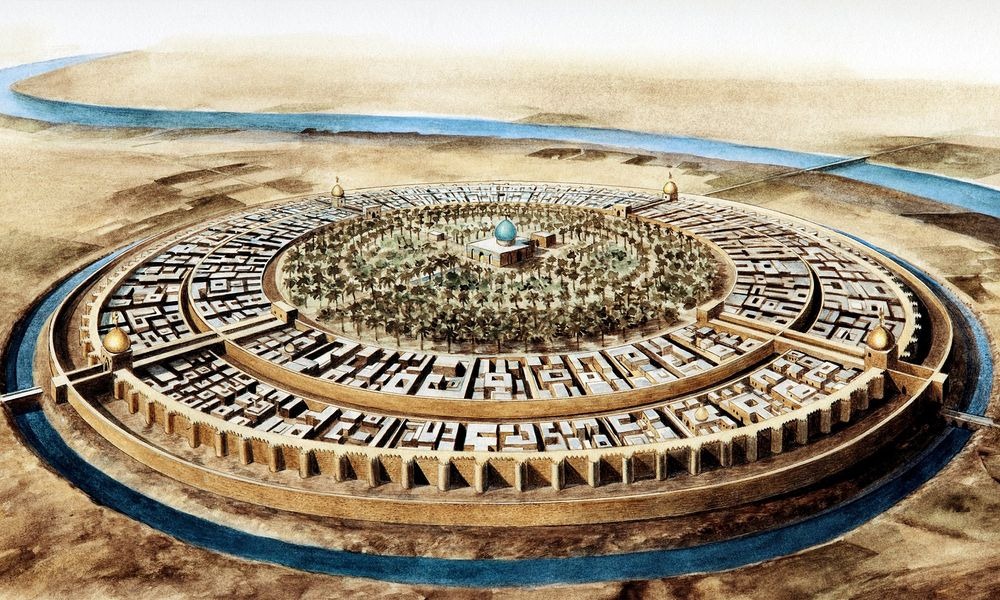

With funds pouring in from the vast Caliphate he had his architects build a circular city with four great gates, radiating boulevards, gardens, and a mosque and palace at its centre.

A model influenced by Persian urban design.

With funds pouring in from the vast Caliphate he had his architects build a circular city with four great gates, radiating boulevards, gardens, and a mosque and palace at its centre.

A model influenced by Persian urban design.

Among the crowning jewels of the Round City of Baghdad was a library built to hold al-Mansur's personal collection of Arabic books and poetry, along with the chronicles and literature of the Sasanians.

It was called the Bayt al-Hikmah — the "House of Wisdom".

It was called the Bayt al-Hikmah — the "House of Wisdom".

The House of Wisdom developed further under al-Mansur's grandson, the fifth caliph, Harun al-Rashid.

And Baghdad itself, sitting on vital trade routes from east to west, flourished under al-Rashid, even becoming the world's largest city in the early 9th century.

And Baghdad itself, sitting on vital trade routes from east to west, flourished under al-Rashid, even becoming the world's largest city in the early 9th century.

Scholars flocked to the House of Wisdom from all over the Caliphate.

Along with librarians, binders, copyists, translators... this was both a treasury of ancient texts and a place of study, of medicine, mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, of music and poetry and literature.

Along with librarians, binders, copyists, translators... this was both a treasury of ancient texts and a place of study, of medicine, mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, of music and poetry and literature.

It peaked under the seventh caliph, al-Mamun, who patronised the "Translation Movement" a state-funded effort to translate Ancient Greek texts into Arabic.

He also appointed the Persian scholar al-Khwarizmi — the father of algebra — as head of the Bayt al-Hikmah.

He also appointed the Persian scholar al-Khwarizmi — the father of algebra — as head of the Bayt al-Hikmah.

Thus the House of Wisdom has come to embody the Islamic Golden Age.

It lay at the centre of the Islamic world, Baghdad, an institution simultaneously preserving the past and striding into the future.

A beacon of literacy, enlightenment, science, culture, and education.

It lay at the centre of the Islamic world, Baghdad, an institution simultaneously preserving the past and striding into the future.

A beacon of literacy, enlightenment, science, culture, and education.

And Baghdad as a whole became a city legendary around the world, from the Tang Dynasty in China to the Franks in Europe, for its size, wealth, luxury, and sophistication.

Indeed, the famous "One Thousand and One Nights" is set during the splendid reign of Harun al-Rashid.

Indeed, the famous "One Thousand and One Nights" is set during the splendid reign of Harun al-Rashid.

Alas, the great wheel of history churned and Baghdad's days of glory faded.

Al-Mu'tasim, the eight caliph, moved the capital to Samarra — and the Abbasid Caliphate fractured into the Ayyubids, Fatimids, Mamluks, Buyids, Seljuks, and even an Umayyad resurgence in Spain.

Al-Mu'tasim, the eight caliph, moved the capital to Samarra — and the Abbasid Caliphate fractured into the Ayyubids, Fatimids, Mamluks, Buyids, Seljuks, and even an Umayyad resurgence in Spain.

But even if Baghdad was diminished the House of Wisdom survived as a treasury of old books.

Until, in the 13th century, world history changed course again.

A new power emerged that would exceed in pace and scale even those Islamic conquests of the 7th century...

Until, in the 13th century, world history changed course again.

A new power emerged that would exceed in pace and scale even those Islamic conquests of the 7th century...

Genghis Khan came storming out of Mongolia and within three generations his family had established the largest contiguous state in human history, before or since.

And it was Genghis Khan's grandson, Hulegu Khan, who laid siege to Baghdad in 1258.

And it was Genghis Khan's grandson, Hulegu Khan, who laid siege to Baghdad in 1258.

The city was conquered, its treasures sacked, its people slaughtered, its buildings burned.

The Round City of Baghdad, the crowning jewel of the Abbasid Caliphate, the glorious capital of Harun al-Rashid, and the House of Wisdom... it was over.

The Round City of Baghdad, the crowning jewel of the Abbasid Caliphate, the glorious capital of Harun al-Rashid, and the House of Wisdom... it was over.

And thus, like the Library of Alexandria, destroyed during the chaos of the Roman civil wars, the House of Wisdom was lost to time.

Who knows what it contained? Who knows of what treastures posterity has been deprived?

We will never know.

Who knows what it contained? Who knows of what treastures posterity has been deprived?

We will never know.

The House of Wisdom speaks to the greatness of Baghdad under of the Abbasids, and of the Islamic Golden Age more broadly.

And, like the Library of Alexandria before it, the House of Wisdom reminds us, even in our digital 21st century, that civilisation is fragile...

And, like the Library of Alexandria before it, the House of Wisdom reminds us, even in our digital 21st century, that civilisation is fragile...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh