This photo is 113 years old.

It was taken by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, an early pioneer of colour photography.

If you've ever wondered what the world used to look like, Prokudin-Gorsky's photos will show you...

It was taken by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, an early pioneer of colour photography.

If you've ever wondered what the world used to look like, Prokudin-Gorsky's photos will show you...

Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky was born to an aristocratic family in rural Russia in 1863.

He studied chemistry in St Petersburg under the creator of the periodic table, Dmitri Mendeleev, and also took art classes.

And he combined these two passions by devoting himself to photography.

He studied chemistry in St Petersburg under the creator of the periodic table, Dmitri Mendeleev, and also took art classes.

And he combined these two passions by devoting himself to photography.

Prokudin-Gorsky wanted to master colour photography — he saw it as a force for education and for documenting history.

Though black and white was the norm, a German chemist called Adolf Miethe had been experimenting with colour.

So he travelled to Berlin to study with him.

Though black and white was the norm, a German chemist called Adolf Miethe had been experimenting with colour.

So he travelled to Berlin to study with him.

He returned to Russia and in the early 1900s set up his own studio — and started producing colour photographs, including one of Leo Tolstoy.

These were shown to Tsar Nicholas II, who happily gave Prokudin-Gorsky the funds to travel across and photograph the vast Russian Empire.

These were shown to Tsar Nicholas II, who happily gave Prokudin-Gorsky the funds to travel across and photograph the vast Russian Empire.

So Prokudin-Gorsky set out in a train with a specially-fitted dark room carriage, plus royal permission to go wherever he wanted.

There was hardly anything he didn't photograph: churches, mosques, rivers, peasants, relics, fields, trains, bridges... a chronicle of his times.

There was hardly anything he didn't photograph: churches, mosques, rivers, peasants, relics, fields, trains, bridges... a chronicle of his times.

It's hard to grasp how miraculous his photographs must have been back then.

Just compare one of Prokudin-Gorsky's colour photographs with his work in black and white to see the difference.

A new and technicolour world: lush, radiant, glistening, thrilling... real!

Just compare one of Prokudin-Gorsky's colour photographs with his work in black and white to see the difference.

A new and technicolour world: lush, radiant, glistening, thrilling... real!

Some of his best photographs were taken in Samarqand, in Uzbekistan, which under Timur in the 14th century had been one of the largest, richest, and most beautiful cities in the world.

Here we see Timur's mausoleum, then six hundred years old.

Here we see Timur's mausoleum, then six hundred years old.

And here the Registan, the fabulous complex of three madrasahs in the heart of the city, then in a state of relative disrepair.

Prokudin-Gorsky had used his chemical expertise to become a master of colour photography.

It was a complex process... but he had found a way.

Prokudin-Gorsky had used his chemical expertise to become a master of colour photography.

It was a complex process... but he had found a way.

The architecture of Samarqand has been restored since Prokudin-Gorsky's photos were taken.

Like the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, one of the largest in the world when it was built in the 15th century, a testament to the greatness of the Timurids.

Like the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, one of the largest in the world when it was built in the 15th century, a testament to the greatness of the Timurids.

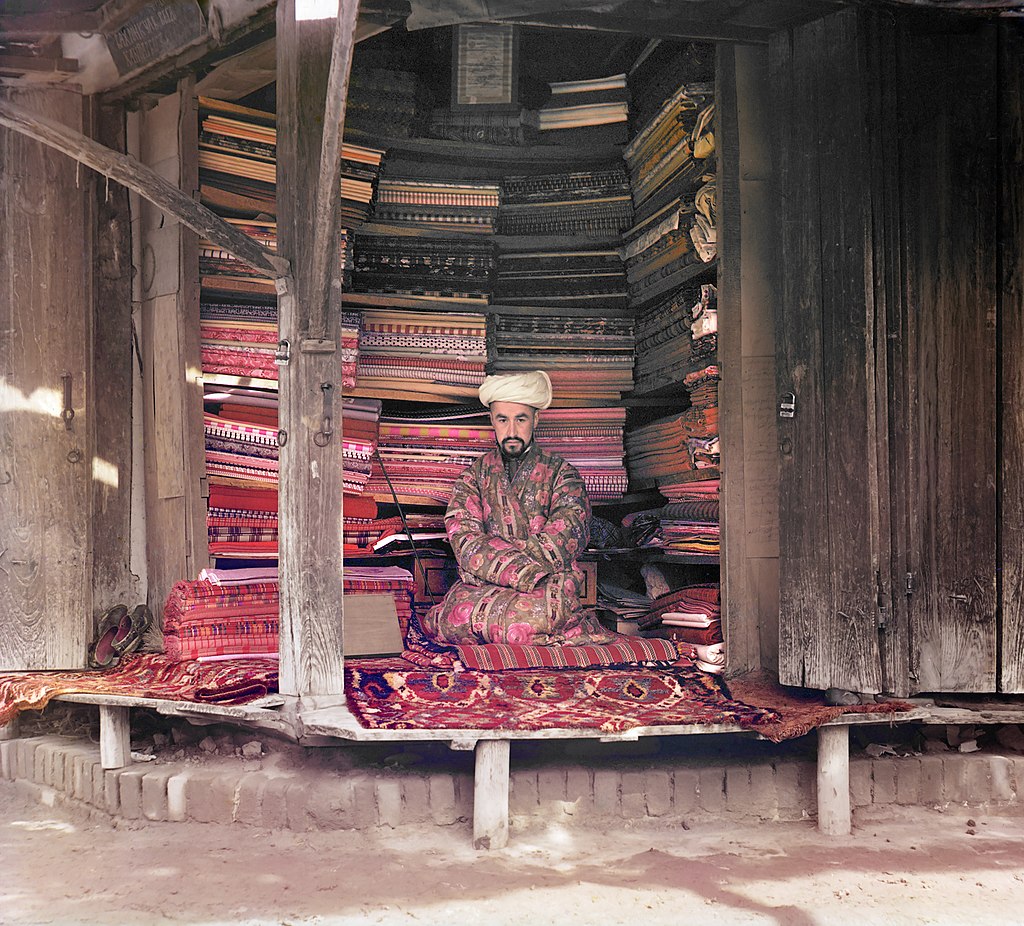

But perhaps the most striking pictures are those of the ordinary people of Samarqand, whether melon sellers and fabric merchants.

Or doctors and water-carriers.

It almost seems hard to believe that these photos were taken more than one hundred years ago.

But they were, and they give us beautifully crisp details from the past, down to every brick and speck of dust.

It almost seems hard to believe that these photos were taken more than one hundred years ago.

But they were, and they give us beautifully crisp details from the past, down to every brick and speck of dust.

Prokudin-Gorsky also went to Bukhara, where he photographed Alim Khan, the last ruler of the Emirate of Bukhara.

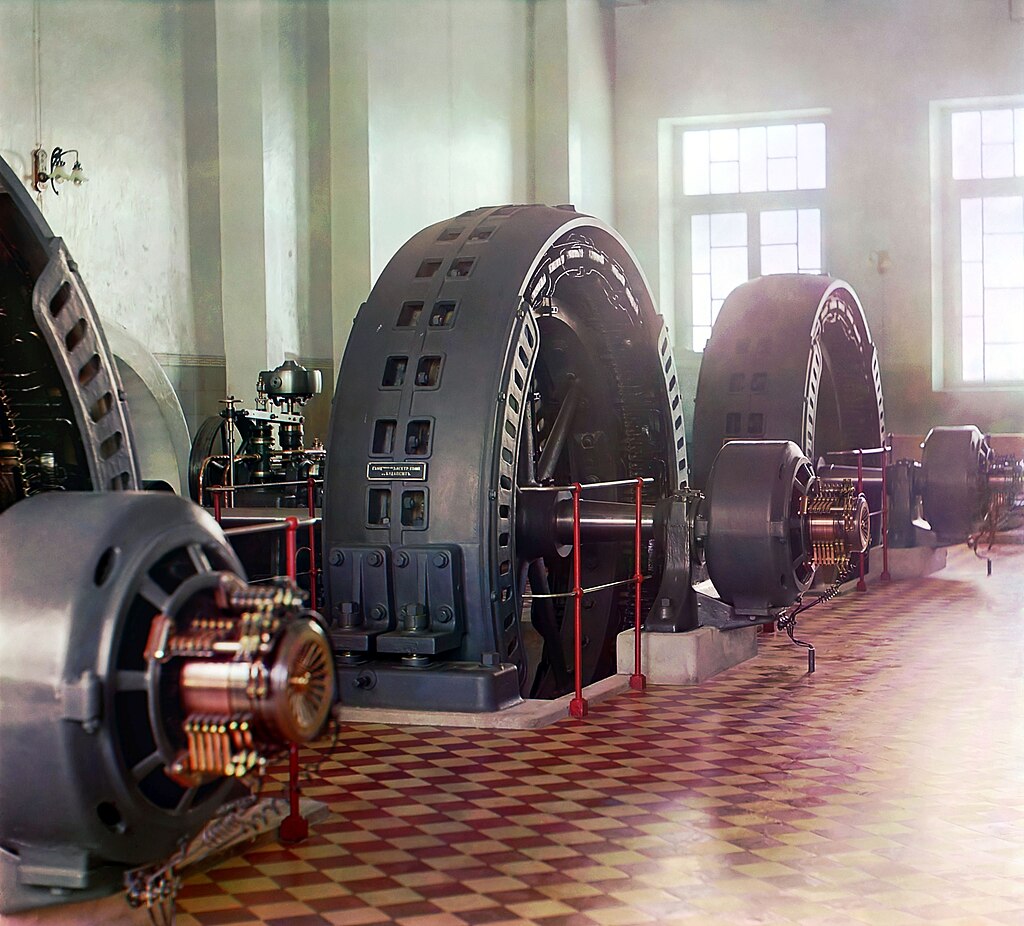

Change was coming: politically, in the shape of the Soviet Union, and technologically, as the Industrial Revolution fundamentally reshaped global society.

Change was coming: politically, in the shape of the Soviet Union, and technologically, as the Industrial Revolution fundamentally reshaped global society.

Thus Prokudin-Gorsky's photographs give us a vivid glimpse into a world on the verge of changing forever, on the verge of being lost.

Here we see a nomadic Kyrgyz family:

Here we see a nomadic Kyrgyz family:

Prokudin-Gorsky gives us endless vignettes of life in those long-gone times, whether a village in Turkmenistan or an old canal supervisor in his uniform:

Here we see the crumbling Sultan Sanjar Mausoleum in Merv, Turkmenistan, originally built in the 12th century.

It has been fully restored since then, and so Prokudin-Gorsky shows it to us as we can no longer see it — authentically.

It has been fully restored since then, and so Prokudin-Gorsky shows it to us as we can no longer see it — authentically.

The clothes of the people photographed by Prokudin-Gorsky stand out.

Black and white photographs lull us into thinking that the past was a less colourful time than now.

The rich and technicolour clothes of these people tell a different story, however.

Black and white photographs lull us into thinking that the past was a less colourful time than now.

The rich and technicolour clothes of these people tell a different story, however.

The past was not the grim and colourless era we see often see in in cinema or television, and peasants did not all wear drab and filthy rags.

One thing you can't help but notice is how these landscapes are dominated by churches.

Such towers are still impressive now — but back then, when most buildings were small and wooden, these churches were the tallest and grandest structures by far.

Such towers are still impressive now — but back then, when most buildings were small and wooden, these churches were the tallest and grandest structures by far.

Just look at how they soar above the urban landscapes.

A reminder of how much more important religion was in those days; you learn a lot from a society's biggest buildings.

A reminder of how much more important religion was in those days; you learn a lot from a society's biggest buildings.

It's also worth considering how many things we now consider normal *aren't* present in these photographs.

Whether materials like concrete, steel, and plate glass, or infrastructure like pylons and highways.

This was how the world looked for most of human history.

Whether materials like concrete, steel, and plate glass, or infrastructure like pylons and highways.

This was how the world looked for most of human history.

Thus Prokudin-Gorsky's photographs of industry, of railways and bridges and factories, stand out all the more.

Here we see our modern world emerging:

Here we see our modern world emerging:

There are many more photographs, all of them fascinating, transporting, instructive, and quite beautiful.

Somehow, simply by virtue of being in colour, we see the past face to face — it comes to life.

Somehow, simply by virtue of being in colour, we see the past face to face — it comes to life.

Prokudin-Gorsky's work almost didn't survive.

He moved to Paris and there his sons stored his photographs in a basement, unsure what to do with them, where they slowly deteriorated.

Until 1948, when they were bought by US Library of Congress.

He moved to Paris and there his sons stored his photographs in a basement, unsure what to do with them, where they slowly deteriorated.

Until 1948, when they were bought by US Library of Congress.

The surviving photographs have since been digitised and restored by experts so that, now, Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky's quest to document his times has finally been fulfilled.

His painstaking, pioneering, passionate work opens a rare window into the past, into the world that was...

His painstaking, pioneering, passionate work opens a rare window into the past, into the world that was...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh