What does Satan look like?

Strange, disturbing, and unintentionally funny: this is a brief history of the Devil in art...

Strange, disturbing, and unintentionally funny: this is a brief history of the Devil in art...

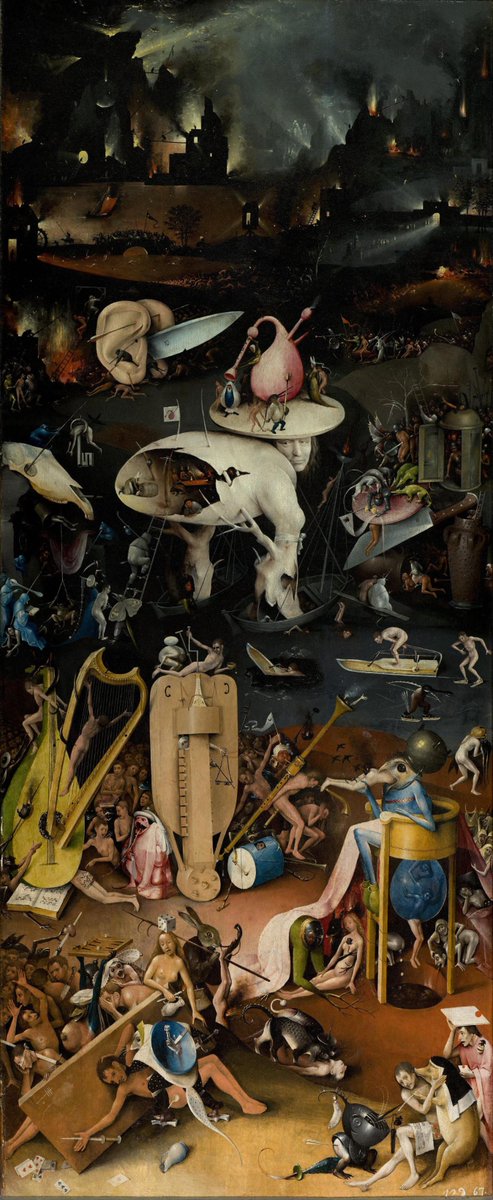

The Garden of Earthly Delights, painted by Hieronymus Bosch at the beginning of the 16th century, is probably the most famous portrayal of Hell in art.

What's most striking about it is that Bosch does not just portray the Devil as evil — here he is utterly insane.

What's most striking about it is that Bosch does not just portray the Devil as evil — here he is utterly insane.

But Bosch is not unique.

He was part of a broad Lade Medieval tradition whereby Hell and the things in it — including the Devil — were depicted, above all else, as *strange*.

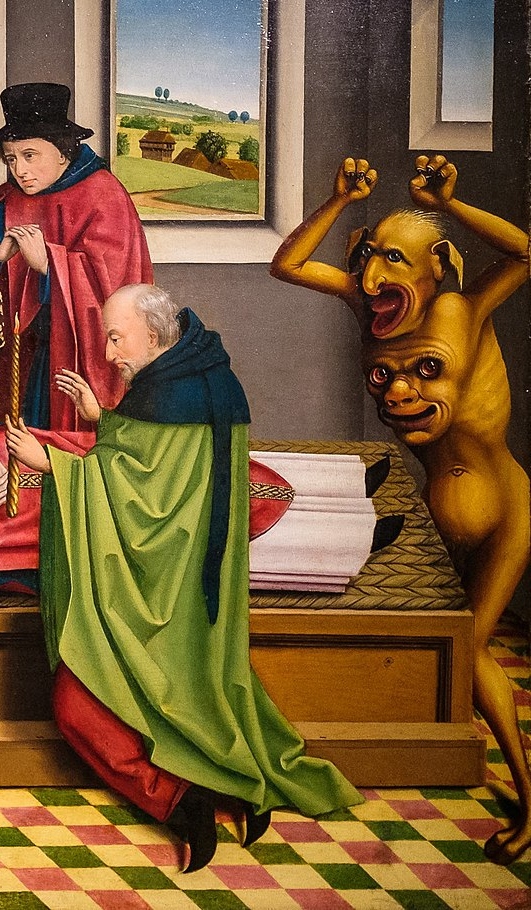

The Harrowing of Hell, by one of Bosch's followers, continues to indulge that same fiery madness.

He was part of a broad Lade Medieval tradition whereby Hell and the things in it — including the Devil — were depicted, above all else, as *strange*.

The Harrowing of Hell, by one of Bosch's followers, continues to indulge that same fiery madness.

Or consider Pieter Brueghel the Elder's Fall of the Rebel Angels, painted in the 1560s; it depicts Lucifer and his followers being cast out of Heaven.

Zoom in and look at the details — some of them are almost inexplicably bizarre.

Surreal, darkly funny, and dreamlike terror.

Zoom in and look at the details — some of them are almost inexplicably bizarre.

Surreal, darkly funny, and dreamlike terror.

Bartolomé Bermejo, a 15th century Spanish painter who travelled to the Netherlands and there learned the art of oil painting, created one of the most memorable versions of the Devil.

A metallic beetle-monster whose every limb is a different creature, whose very joints are jaws.

A metallic beetle-monster whose every limb is a different creature, whose very joints are jaws.

In Italy, meanwhile, Fra Angelico — most famous for his pious and pure paintings of saints — conjured this foul beast.

The Renaissance was coming, but the Late Medieval imagination still held sway with its unbounded embrace of sheer and fantastical strangness:

The Renaissance was coming, but the Late Medieval imagination still held sway with its unbounded embrace of sheer and fantastical strangness:

Though, that being said, the Middle Ages also produced some of the most unintentionally funny devils...

But the Devil has not always looked so strange.

As the influence of the Renaissance spread, the imaginative scope of artists also seemed to shrink.

Guido Reni's 1636 version of St Michael triumphing over Satan simply depicts him as an evil-looking man with wings.

As the influence of the Renaissance spread, the imaginative scope of artists also seemed to shrink.

Guido Reni's 1636 version of St Michael triumphing over Satan simply depicts him as an evil-looking man with wings.

Though, done well, this modern trope of the Devil as a winged man can be rather frightening.

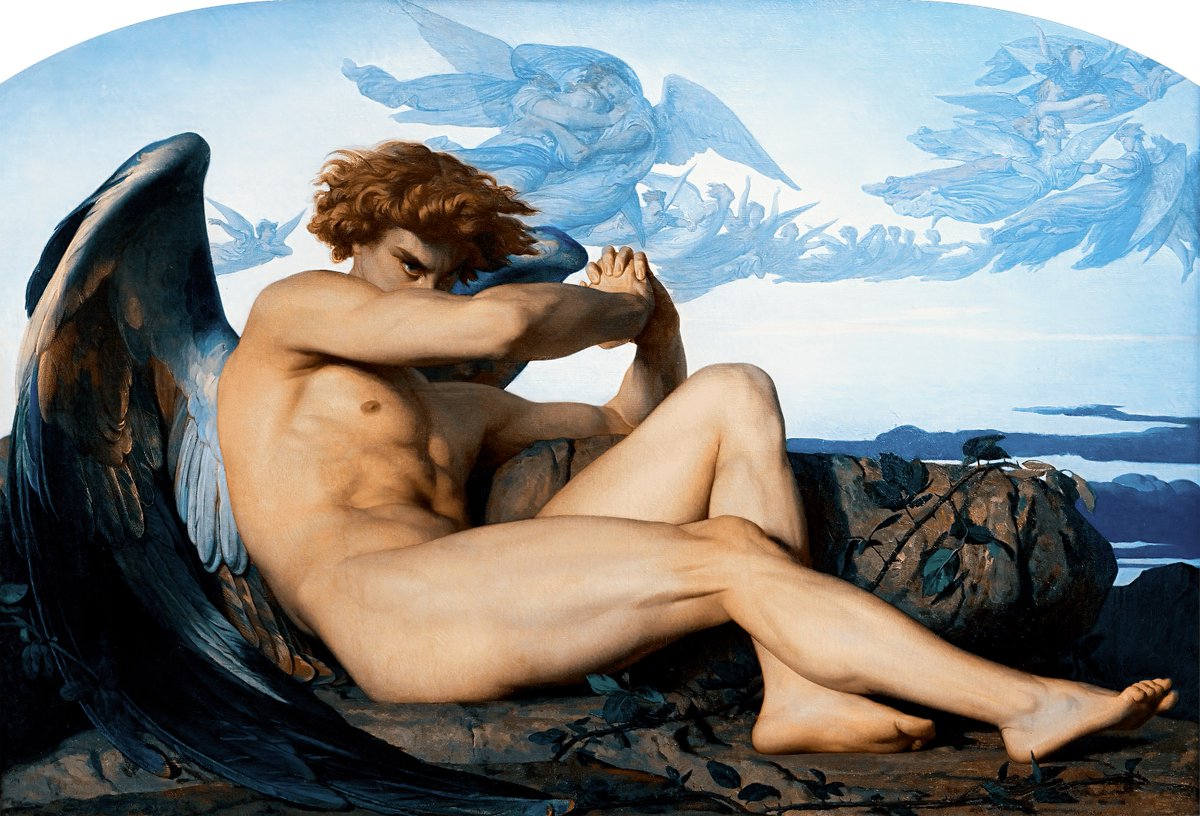

Alexandre Cabanel's famous Fallen Angel, from 1847, has an almost disturbingly dark intensity, all because of the expression on his face.

Sometimes you don't need flames or monsters.

Alexandre Cabanel's famous Fallen Angel, from 1847, has an almost disturbingly dark intensity, all because of the expression on his face.

Sometimes you don't need flames or monsters.

Any discussion of Hell must include Dante and his famous Inferno, where Satan is described as a huge three-headed monster submerged in a sea of ice.

But, sometimes, when a thing is too well described it becomes less scary — is not mystery the most frightening thing of all?

But, sometimes, when a thing is too well described it becomes less scary — is not mystery the most frightening thing of all?

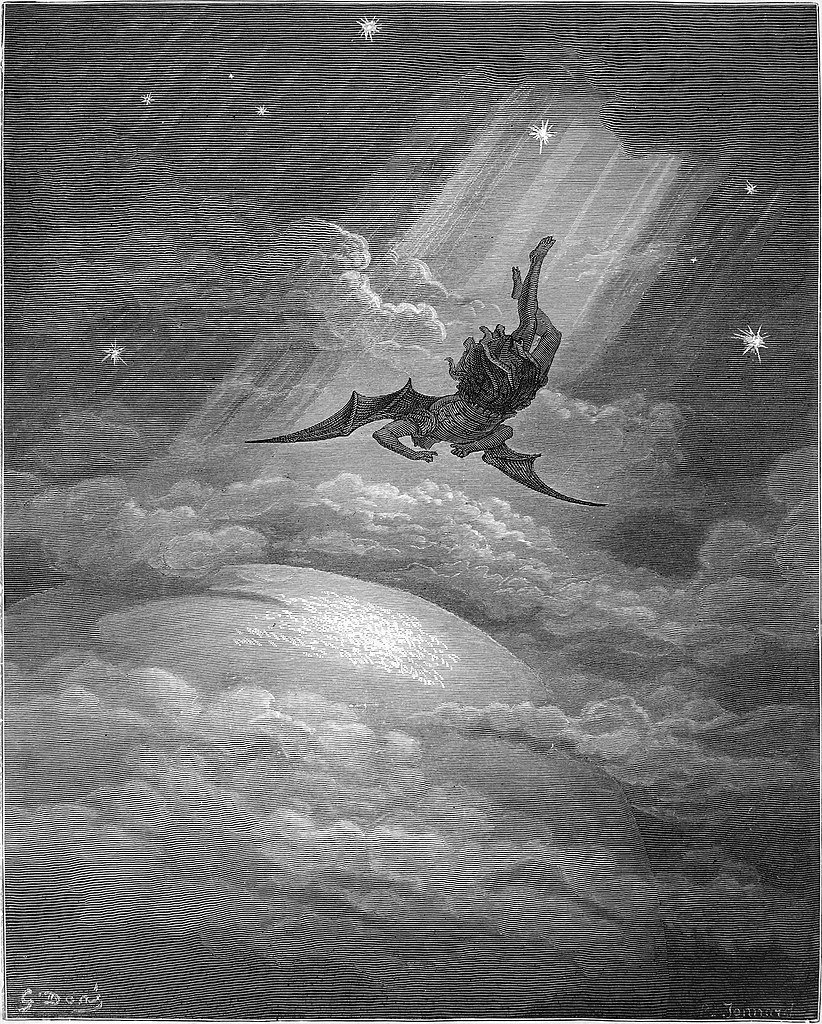

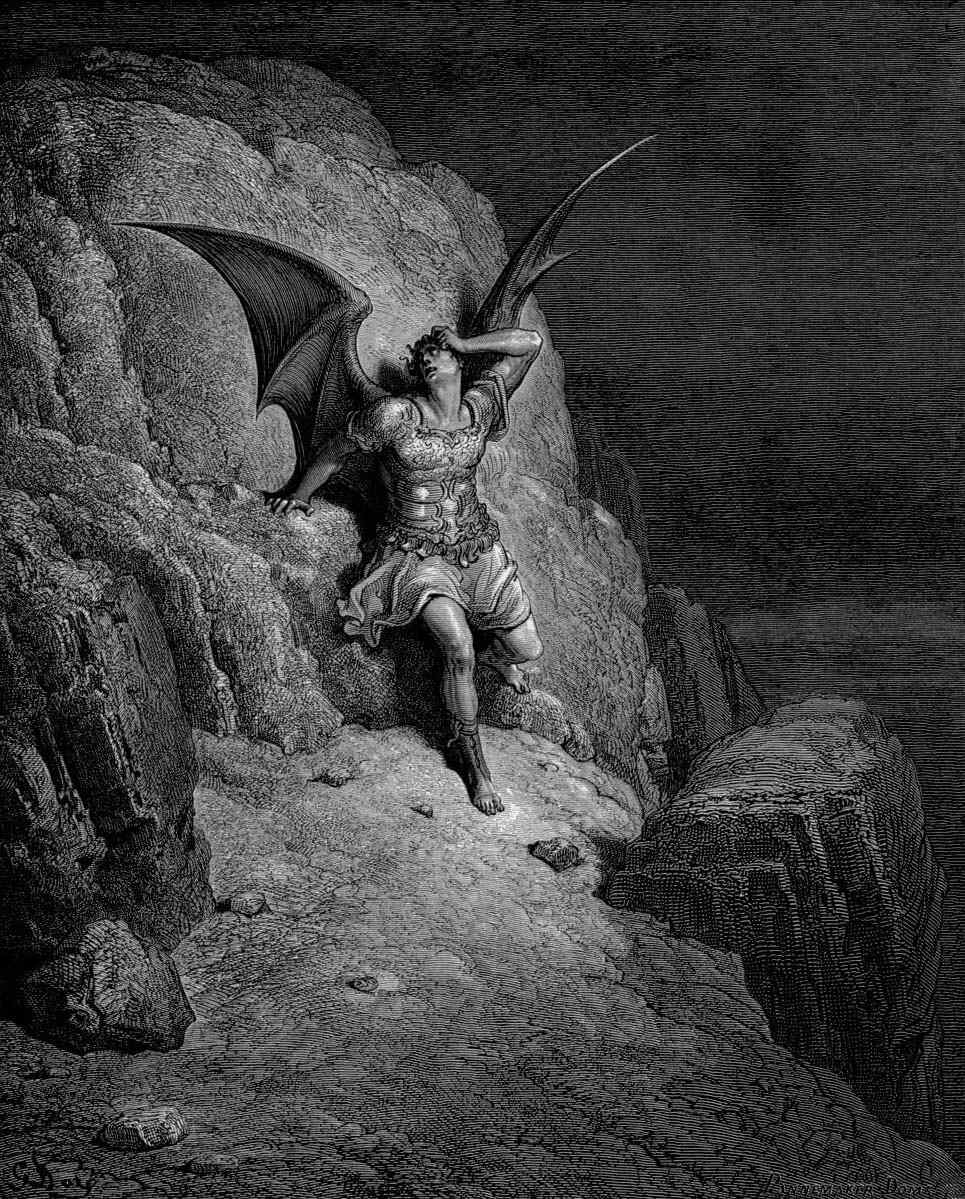

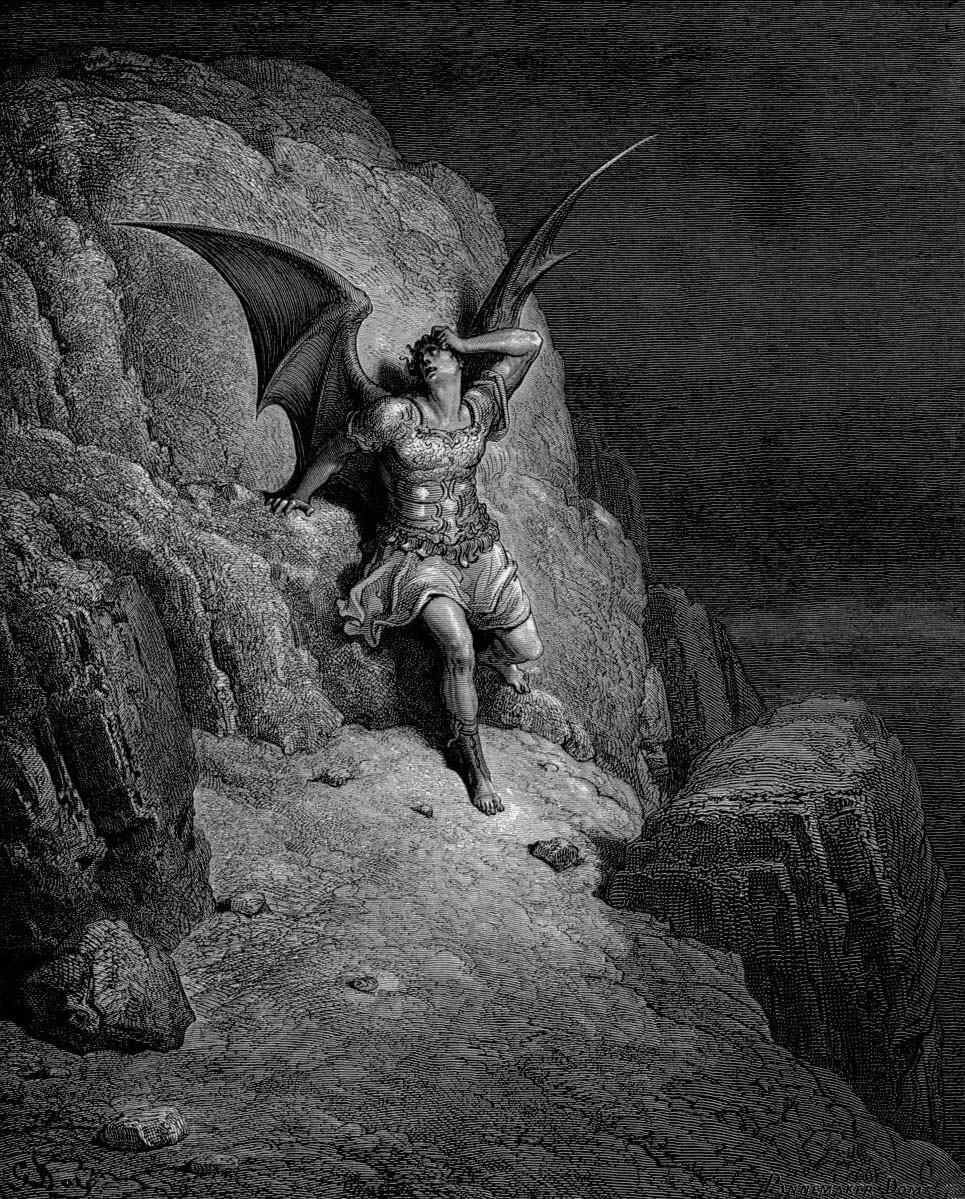

Gustave Doré was a 19th century French artist who, among other poems and books, made illustrations for John Milton's Paradise Lost, a 17th century epic poem where Satan is (sort of) the protagonist.

Satan as a character may be more engaging, but it is perhaps less frightening.

Satan as a character may be more engaging, but it is perhaps less frightening.

But these dramatic and characterised portrayals became more common.

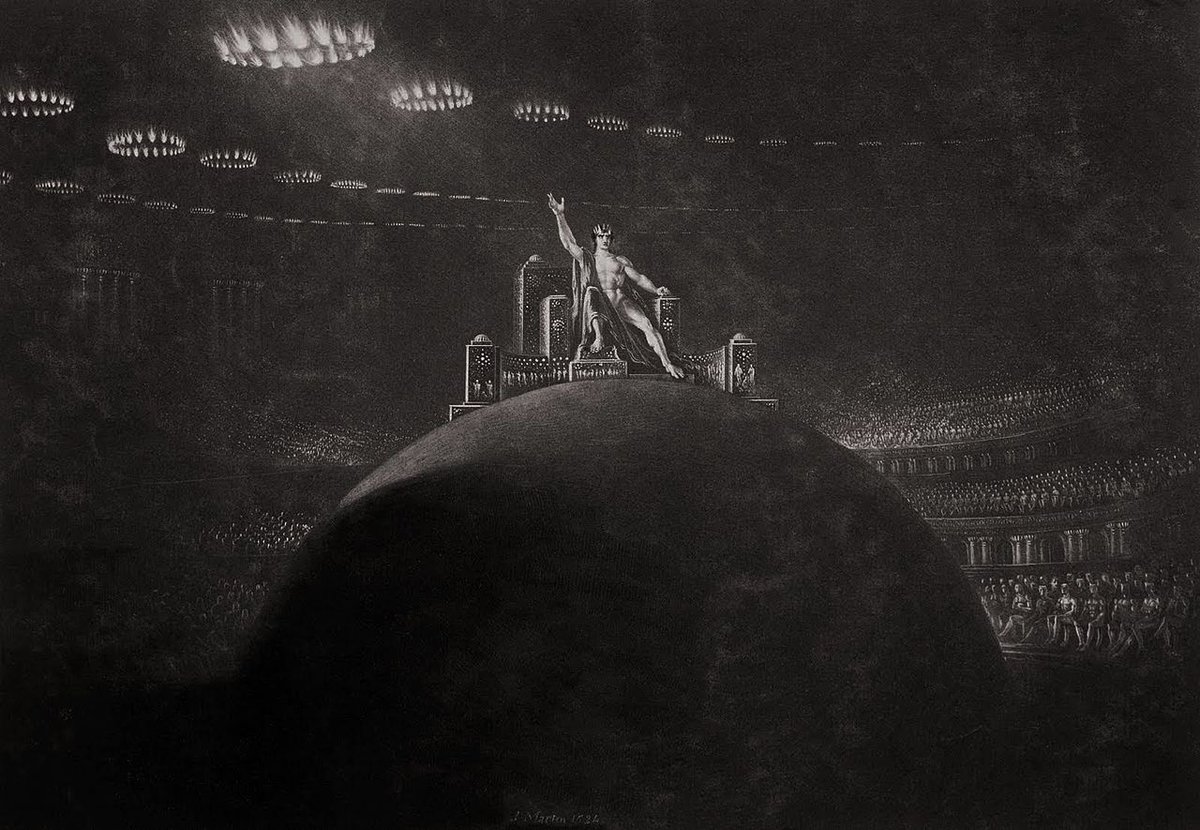

From the genuinely disturbing devils of the Middle Ages we move to something like Pandemonium, by the 19th century English painter John Martin

This scene, epic in scale, is almost cinematic.

From the genuinely disturbing devils of the Middle Ages we move to something like Pandemonium, by the 19th century English painter John Martin

This scene, epic in scale, is almost cinematic.

John Martin also made Satan Presiding Over His Infernal Council, which again leans into that epic scale and grand narrative.

Satan as a dramatic character is certainly more compelling, but that sense of the visceral horror of evil has perhaps been lost.

Satan as a dramatic character is certainly more compelling, but that sense of the visceral horror of evil has perhaps been lost.

Some of the most frightening paintings of the Devil are the least dramatic.

Rather than reigning in a realm of flames or appearing as a fantastical beast, the Devil is more chilling when portrayed as part of the real world.

Albrecht Dürer's devil is skin-crawlingly creepy.

Rather than reigning in a realm of flames or appearing as a fantastical beast, the Devil is more chilling when portrayed as part of the real world.

Albrecht Dürer's devil is skin-crawlingly creepy.

And then there is something like the Witches' Sabbath by Francesco Goya.

Goya's talent for painting faces strained with anguish and torn apart by lunacy only enhances the overwhelming creepiness of this painting.

Goya's talent for painting faces strained with anguish and torn apart by lunacy only enhances the overwhelming creepiness of this painting.

Along similar lines is Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare, from 1781.

Although it doesn't portray the Devil, strictly speaking, as a vision of evil it is almost oppressively dark.

Although it doesn't portray the Devil, strictly speaking, as a vision of evil it is almost oppressively dark.

Sometimes you don't need to be graphic.

In Giotto's painting of Judas betraying Jesus, from the early 1300s, we simply see a dark figure embracing him.

This is somehow more unsettling than any strange monster or colossal beast... a mere shadow.

In Giotto's painting of Judas betraying Jesus, from the early 1300s, we simply see a dark figure embracing him.

This is somehow more unsettling than any strange monster or colossal beast... a mere shadow.

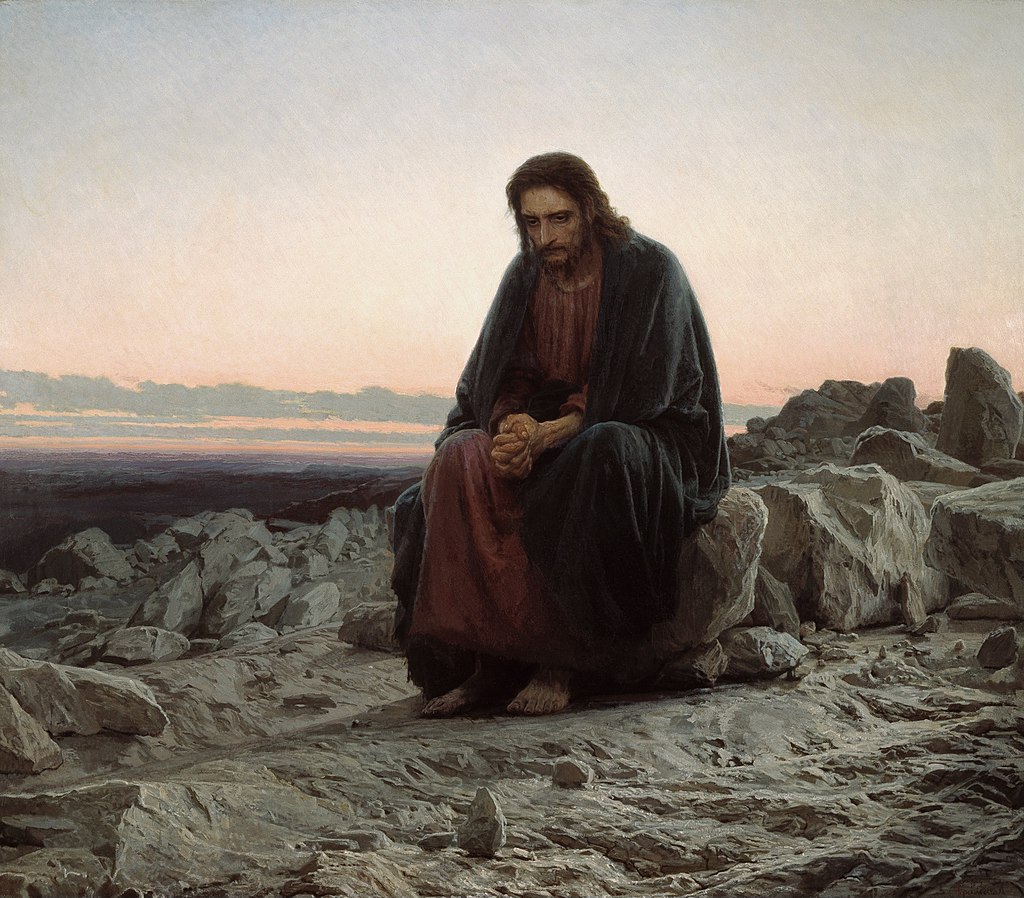

And perhaps the most striking paintings of the Devil don't even include him.

Like Christ in the Wilderness, painted by Ivan Kramskoy in 1872, where by his very absence the Devil feels more real, more invisibly and universally present, than ever.

Like Christ in the Wilderness, painted by Ivan Kramskoy in 1872, where by his very absence the Devil feels more real, more invisibly and universally present, than ever.

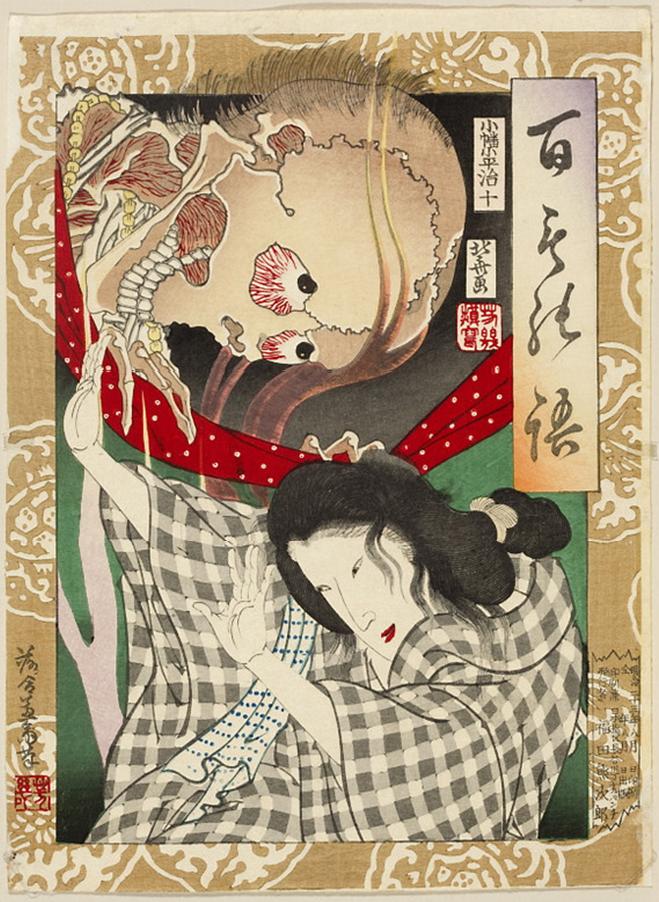

Of course, the Devil is not only a Christian concept — other religions have similar ideas of evil creatures, spirits, and demons, and there is a whole world of strange and terrifying art out there.

There is no single way to portray evil — so what is it, specifically, that makes paintings of the Devil frightening to you?

Is it when we see something horrifying and strange, something otherworldly, or a scene of total mundanity?

Is it when we see something horrifying and strange, something otherworldly, or a scene of total mundanity?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh