🧵regarding the 117 deaths in The Iliad where Homer provided details about the mechanism of injury:

Here we will run an M&M conference to consider whether these deaths might have been preventable if the Achaeans and Trojans had modern Level 1 trauma centers at the time.

(1/ )

Here we will run an M&M conference to consider whether these deaths might have been preventable if the Achaeans and Trojans had modern Level 1 trauma centers at the time.

(1/ )

Background:

Recently, I read 'The Iliad' and noticed how often Homer described deaths with anatomic detail.

I then decided to look at these cases as though they occurred near a modern Level 1 trauma center with full capabilities.

Butler's 1898 English translation was used.

Recently, I read 'The Iliad' and noticed how often Homer described deaths with anatomic detail.

I then decided to look at these cases as though they occurred near a modern Level 1 trauma center with full capabilities.

Butler's 1898 English translation was used.

Methods:

Assumptions and simplifications included:

- The Achaeans and Trojans each have their own trauma centers

- rapid 'scoop and run' prehospital transport

- the cases present individually, and there are no 'mass casualty' scenarios that would overwhelm the system.

Assumptions and simplifications included:

- The Achaeans and Trojans each have their own trauma centers

- rapid 'scoop and run' prehospital transport

- the cases present individually, and there are no 'mass casualty' scenarios that would overwhelm the system.

Head injuries in The Iliad appeared to be the most lethal.

22 head injuries were non-preventable. These included both blunt and penetrating mechanisms, with 7 beheadings.

3 blunt head injuries were 'possibly' preventable. The utility of ICP monitors was unknown 🤔.

22 head injuries were non-preventable. These included both blunt and penetrating mechanisms, with 7 beheadings.

3 blunt head injuries were 'possibly' preventable. The utility of ICP monitors was unknown 🤔.

Neck injuries were common, and were as follows:

9 - nonpreventable

3 - possibly preventable

4 - preventable

Face injuries occurred in a few cases:

4 were possibly preventable and 2 were preventable.

Airway interventions might have helped in at least 8 of the neck/face cases.

9 - nonpreventable

3 - possibly preventable

4 - preventable

Face injuries occurred in a few cases:

4 were possibly preventable and 2 were preventable.

Airway interventions might have helped in at least 8 of the neck/face cases.

Chest injuries were common.

R sided injuries were thought to be more survivable, and presumed cardiac injuries from spears were considered fatal.

There were 24 deaths:

- 9 non-preventable

- 11 possibly preventable

- 4 preventable

Chest tubes may have been lifesaving for many.

R sided injuries were thought to be more survivable, and presumed cardiac injuries from spears were considered fatal.

There were 24 deaths:

- 9 non-preventable

- 11 possibly preventable

- 4 preventable

Chest tubes may have been lifesaving for many.

Abdominal trauma:

2 cases were non-preventable

3 cases were possibly preventable

16 cases were likely preventable, including 4 cases of isolated liver injury, and 3 cases of evisceration.

Here was the greatest opportunity for improvement (OFI).

2 cases were non-preventable

3 cases were possibly preventable

16 cases were likely preventable, including 4 cases of isolated liver injury, and 3 cases of evisceration.

Here was the greatest opportunity for improvement (OFI).

Pelvis:

There were 5 deaths from pelvic trauma, all were considered 'preventable'. These included 2 bladder injuries.

1 of these was blunt and might have benefitted from a pelvic binder; whether deployment of a REBOA catheter in zone 3 would have helped is speculative 🤔.

There were 5 deaths from pelvic trauma, all were considered 'preventable'. These included 2 bladder injuries.

1 of these was blunt and might have benefitted from a pelvic binder; whether deployment of a REBOA catheter in zone 3 would have helped is speculative 🤔.

Deaths from isolated injuries to the shoulder region were not rare (9 cases). They occurred more often on the R side.

Cases of simple hemopneumothorax were almost certainly salvageable.

Some may have had subclavian vascular injuries, of which some could have been survivable.

Cases of simple hemopneumothorax were almost certainly salvageable.

Some may have had subclavian vascular injuries, of which some could have been survivable.

Miscellaneous deaths:

2 extremity injuries were preventable with tourniquets.

1 shoulder disarticulation was possibly salvageable (low likelihood).

5 flank wounds and 3 back wounds - all 'possibly' preventable (not enough data)

2 extremity injuries were preventable with tourniquets.

1 shoulder disarticulation was possibly salvageable (low likelihood).

5 flank wounds and 3 back wounds - all 'possibly' preventable (not enough data)

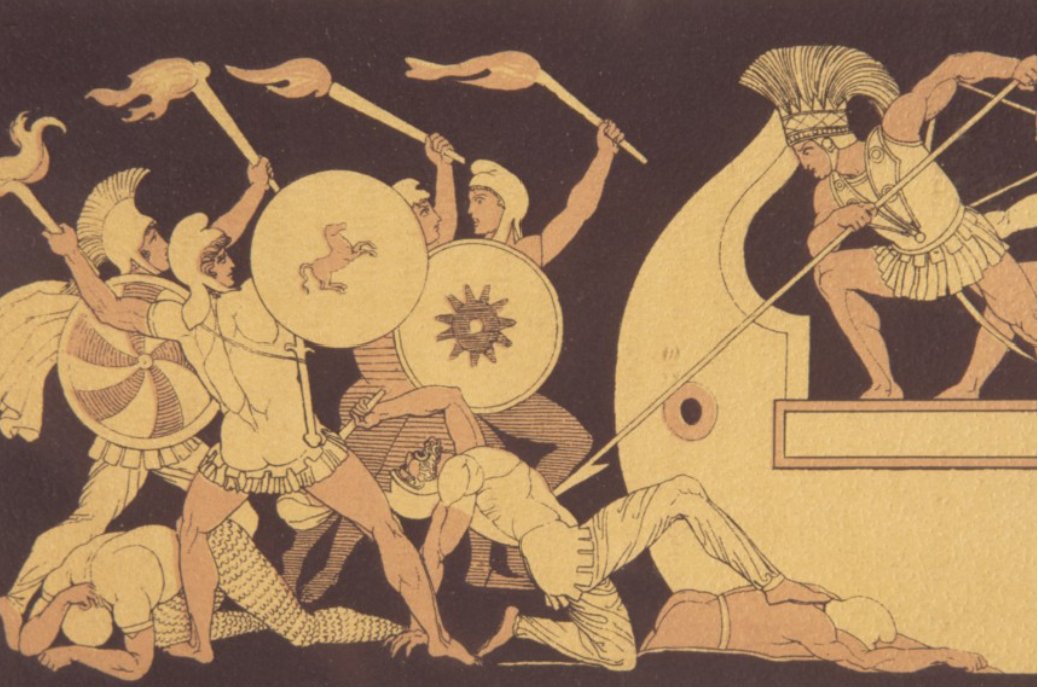

Case review: Hector

In particular the death of Hector is difficult to analyze. The mechanism was clearly an injury to the neck. As described by Butler, it was to 'the fleshy part' of the neck, not involving the trachea. He was able to speak to Achilles afterward, and gradually bled out. This may indicate death from a jugular vein injury, which may well have been preventable.

Artists often depict a transfixing type injury (below) in which the spear also goes into the chest. This may have created an injury to one or more of the aortic arch vessels, which would have been far less salvageable.

In particular the death of Hector is difficult to analyze. The mechanism was clearly an injury to the neck. As described by Butler, it was to 'the fleshy part' of the neck, not involving the trachea. He was able to speak to Achilles afterward, and gradually bled out. This may indicate death from a jugular vein injury, which may well have been preventable.

Artists often depict a transfixing type injury (below) in which the spear also goes into the chest. This may have created an injury to one or more of the aortic arch vessels, which would have been far less salvageable.

In conclusion:

It is estimated that ~40% of the casualties from 'The Iliad' may have been salvageable with modern trauma protocols.

Limitations include the retrospective nature of the study and the incompleteness of medical records in many cases. More studies are needed.

⬛️

It is estimated that ~40% of the casualties from 'The Iliad' may have been salvageable with modern trauma protocols.

Limitations include the retrospective nature of the study and the incompleteness of medical records in many cases. More studies are needed.

⬛️

Addendum:

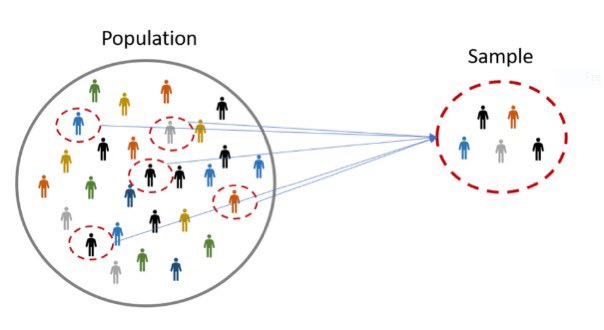

Some may observe that there were far more than 117 deaths in the Iliad.

The remainder either had unspecified mechanisms (many), or were burns (n=12)

Salvageability estimates can likely be extrapolated to the rest (use of the n=117 to do this is called ‘sampling’).

Some may observe that there were far more than 117 deaths in the Iliad.

The remainder either had unspecified mechanisms (many), or were burns (n=12)

Salvageability estimates can likely be extrapolated to the rest (use of the n=117 to do this is called ‘sampling’).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh