Looking for a movie to watch this weekend?

I watched around 250 films from the “classic Hollywood era” of the 1930s-50s, while I was at university.

Screwball comedies, film noir, lots of great films still fun to watch today. Here are my favourites with one-line synopses. 🧵

I watched around 250 films from the “classic Hollywood era” of the 1930s-50s, while I was at university.

Screwball comedies, film noir, lots of great films still fun to watch today. Here are my favourites with one-line synopses. 🧵

First, the comedies:

The Thin Man (1934):

A witty couple solves mysteries with their dog.

(This is the first of six films in The Thin Man series, which are all great)

A witty couple solves mysteries with their dog.

(This is the first of six films in The Thin Man series, which are all great)

The Philadelphia Story (1940):

A socialite's ex-husband and a reporter complicate her wedding plans.

(won an Oscar)

A socialite's ex-husband and a reporter complicate her wedding plans.

(won an Oscar)

Roman Holiday (1953):

A princess escapes her duties and falls for an American reporter in Rome.

(won an Oscar)

A princess escapes her duties and falls for an American reporter in Rome.

(won an Oscar)

My Man Godfrey (1936):

A socialite hires a "forgotten man" to be her family's butler.

(won an Oscar)

A socialite hires a "forgotten man" to be her family's butler.

(won an Oscar)

Indiscreet (1958):

A love affair between a famous actress and a diplomat under false pretense.

A love affair between a famous actress and a diplomat under false pretense.

And now the dramas... 🎭

Gone With The Wind (1939):

A tumultuous love story set against the backdrop of the Civil War.

(won an Oscar)

A tumultuous love story set against the backdrop of the Civil War.

(won an Oscar)

Rebecca (1940):

A young bride is haunted by her husband's glamorous first wife, Rebecca.

(won an Oscar)

A young bride is haunted by her husband's glamorous first wife, Rebecca.

(won an Oscar)

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946):

Three WWII veterans adjust to civilian life with changes and challenges.

(won an Oscar)

Three WWII veterans adjust to civilian life with changes and challenges.

(won an Oscar)

Gentleman's Agreement (1947):

A reporter pretends to be Jewish to expose antisemitism.

(won an Oscar)

A reporter pretends to be Jewish to expose antisemitism.

(won an Oscar)

The Country Girl (1954):

A director helps a has-been actor and his wife face their demons.

(won an Oscar)

A director helps a has-been actor and his wife face their demons.

(won an Oscar)

Rebel Without A Cause (1955):

A troubled teen forms deep connections while confronting the challenges of adolescence and authority.

A troubled teen forms deep connections while confronting the challenges of adolescence and authority.

All About Eve (1950):

A ambitious young actress schemes to upstage an aging Broadway star.

(won an Oscar)

A ambitious young actress schemes to upstage an aging Broadway star.

(won an Oscar)

To Kill A Mockingbird (1962):

A lawyer defends an innocent black man accused of rape in the deep south.

(won an Oscar)

A lawyer defends an innocent black man accused of rape in the deep south.

(won an Oscar)

Advise and Consent (1962):

Political intrigue unfolds around a controversial Secretary of State nomination.

Political intrigue unfolds around a controversial Secretary of State nomination.

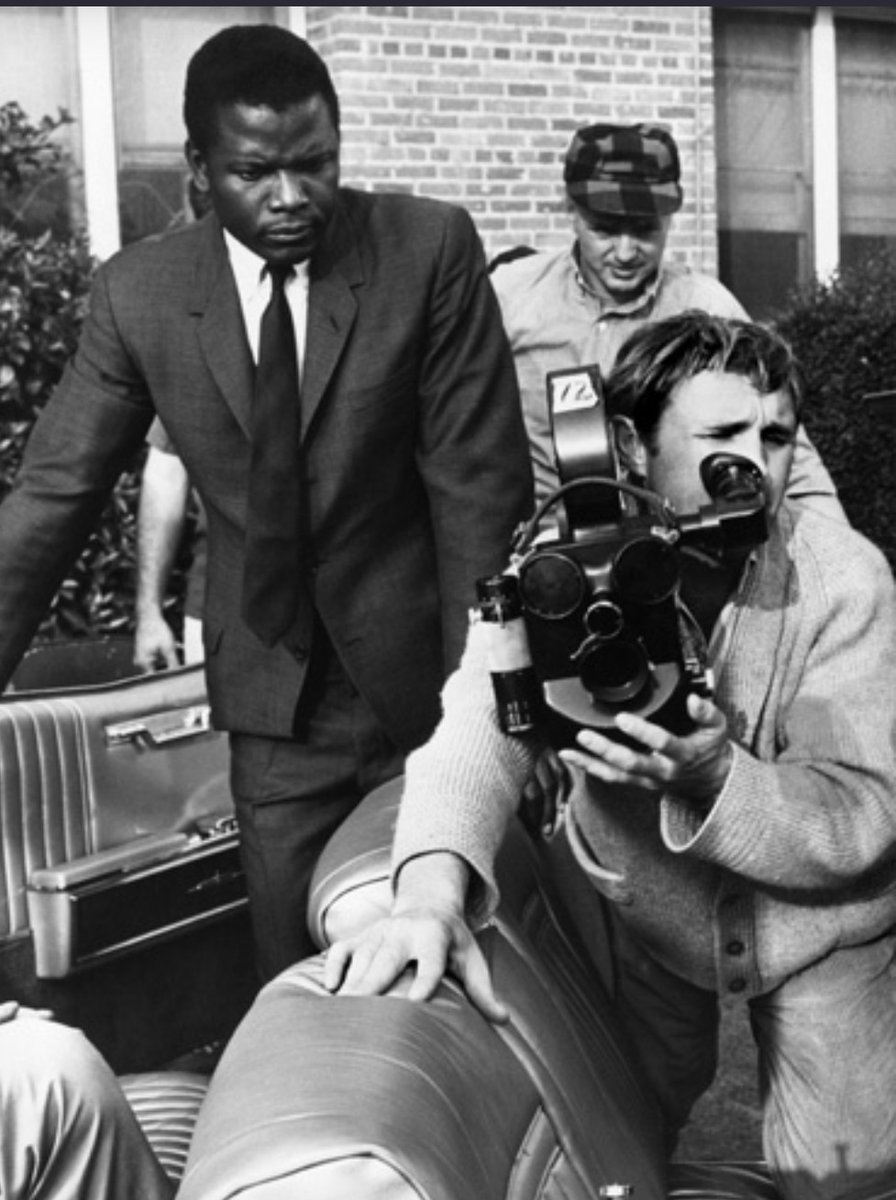

In the Heat of the Night (1967):

A black detective and a white chief of police solve a murder case in a racially tense Southern town.

(won an Oscar)

A black detective and a white chief of police solve a murder case in a racially tense Southern town.

(won an Oscar)

And that's all!

Did I miss any of your favourites?

I might not have seen them... yet 😅

I'm always looking for more to watch, so let me know below!

Did I miss any of your favourites?

I might not have seen them... yet 😅

I'm always looking for more to watch, so let me know below!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh